To the Editor—Implementing a facility-level Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) prevention protocol is a challenging endeavor, and Trick et alReference Trick, Sokalski and Johnson 1 should be commended for their early successes at a large institution. As the manufacturers of the probiotic comprising L. acidophilus CL1285, L. casei LBC80R, and L. rhamnosus CLR2 (Bio-K+), we contributed our products to 9,072 patients for this study at no cost to the investigators as well as monetary support for a research assistant to collect data. We watched the evolution of this quality improvement study in anticipation, receiving regular updates on recruitment and product consumption, though we had no role in the collection or interpretation of the data.

Several issues emerged that made the investigators “unable to electronically extract patient-level antibiotic and probiotic receipt data.” In the absence of a mechanism to review the full dataset of thousands of eligible patients, the authors undertook a case-control study to examine 68 cases and 68 matched controls in detail using a retrospective chart review. One conclusion from this study was that after adjusting for severity of illness, and temporal and spatial proximity, there was “no protective effect from the probiotic.” It is our opinion that the case-control study was rigorous in considering the available data. Many of the known risk factors were controlled, but the principal modifiable risk factor for CDI—antibiotics—was mostly overlooked. Tartof et alReference Tartof, Rieg, Wei, Tseng, Jacobsen and Yu 2 elegantly showed a 2-fold increase in the risk of CDI with each additional antibiotic administered. Among 401,234 adults admitted to Kaiser Permanente Southern California hospitals, 0.5% tested CDI-positive when taking 1 antibiotic, 1.0% when taking 2 antibiotics, and 2.3% when taking 3 or more antibiotics.

It may be, for example, that the composition of a patient’s intestinal microbiota prior to antibiotic exposure is another relevant predictor of susceptibility to C. difficile overgrowth and infection. A detailed metagenomics analysis by Raymond et alReference Raymond, Ouameur and Deraspe 3 of stool samples from healthy volunteers taking an antibiotic uncovered consistent impairments to the diversity and functioning of the gut microbiota and enrichment of resistance genes. In addition, the initial microbiome composition among certain volunteers predicted an overgrowth of known pathogens. Applied to the hospital setting, it could be that hospitalized patients who develop a CDI are inherently more susceptible to the effect of antibiotics on their microbiome. Scientific questions like these are beyond the technical limitations of the case-control design.

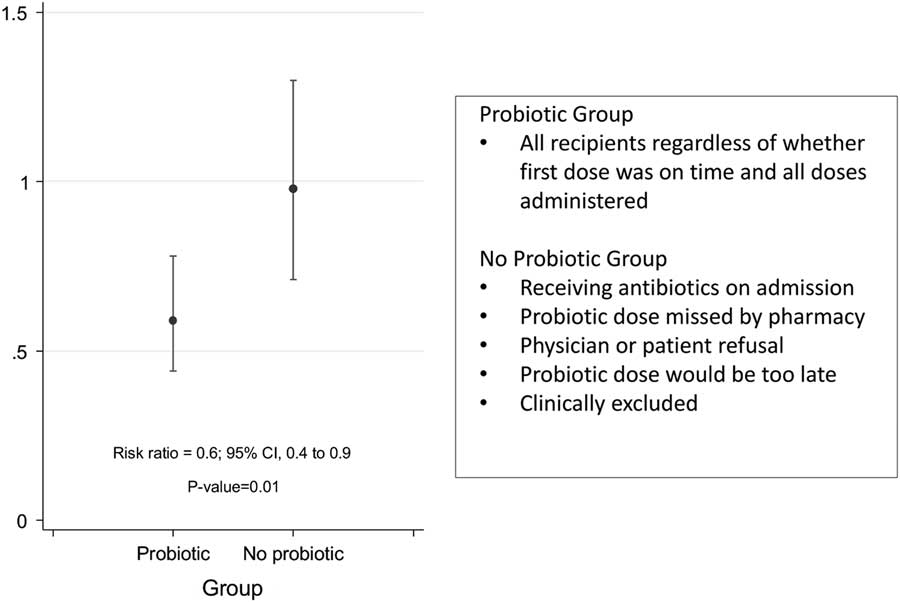

The case-control study did not detect a protective effect, but results from the same cohort presented in 2015 indicate a reduced risk of CDI in patients treated with this probiotic.Reference Trick, Sokalski and Levato 4 A risk ratio of 0.6 (95% CI, 0.4–0.9; P=.01) was calculated, representing a significant protective effect from C. difficile infection for the probiotic recipients (Fig. 1). The inputs for this equation are based on the principal data set collected prospectively within the design of the study, and as such, they do not rely on detailed electronic patient records. Thus, these prospectively collected data suggest that the intervention was having the intended effect.

Fig. 1 Comparison of rates of Clostridium difficile infection (CDI) between probiotic recipients and antibiotic recipients who did not receive a probiotic. [Reproduction from a poster presented at ID Week 2015.]Reference Trick, Sokalski and Levato 4 , Reference Trick, Sokalski and Levato 5

Although Trick et al describe challenges in implementing the protocol, in following patients, and in extracting patient-level data, this quality improvement study provides invaluable information on the real-world practical application of probiotics in the fight against C. difficile infection. As noted in a public release by the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA), it is critically important to test emerging interventions in routine practice and to learn from those experiences. 6 Considering the relative safety and moderate cost of probiotics, practical experiences regarding probiotics implemented for primary CDI prevention are scarce. McFarland et alReference McFarland, Ship, Auclair and Millette 7 recently reviewed the literature evaluating this probiotic (Bio-K+) and idenitified 7 accounts of its implementation at the facility-level for CDI prevention and a few instances with other probiotic formulations. Moving forward, hospitals can learn from the experiences of Trick et al to better address their patients’ vulnerability to CDI with another line of defense.

Acknowledgments

N.S. and S.C. had no role in the collection or interpretation of data published by Trick et al (reference 1).

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

N.S. and S.C. are employees of Bio-K Plus International, the company that partially sponsored the study in question and commercializes the study product.