Article contents

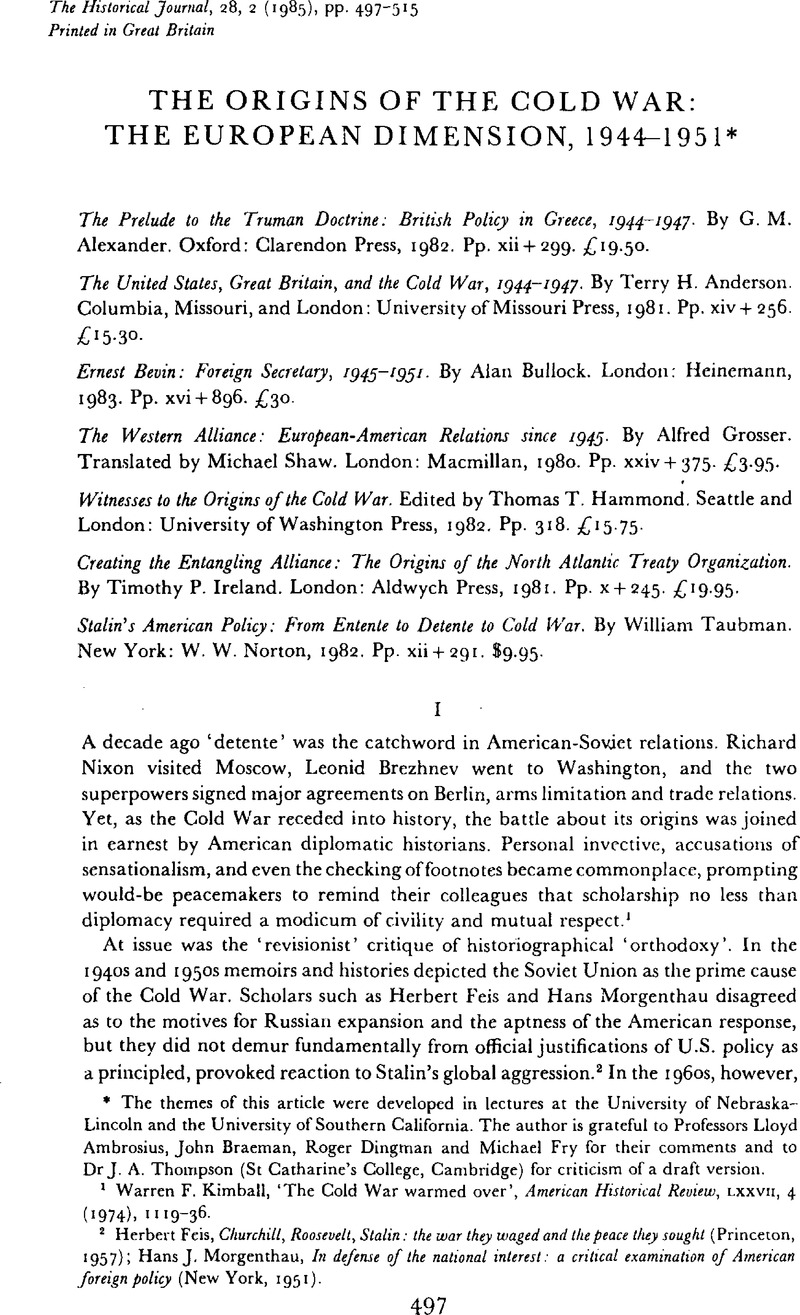

The Origins of the Cold War: The European Dimension,1944–1951*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1985

References

1 Kimball, Warren F., ‘The Cold War warmed over’, American Historical Review, LXXVII, 4 (1974), 1119–36.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

2 Feis, Herbert, Churchill, Roosevelt, Stalin: the war they waged and the peace they sought (Princeton, 1957)Google Scholar; Morgenthau, Hans J., In defense of the national interest: a critical examination of American foreign policy (New York, 1951)Google Scholar.

3 Williams, William Appleman, The tragedy of American diplomacy (rev. edn, New York, 1962)Google Scholar; Alperovitz, Gar, Atomic diplomacy: Hiroshima and Potsdam. The use of the atomic bomb and the American confrontation with Soviet power (New York, 1965)Google Scholar; Joyce, and Kolko, Gabriel, The limits of power: the world and United States foreign policy, 1945–54 (New York, 1972)Google Scholar.

4 Helpful appraisals can be found in Maier, Charles S., ‘Revisionism and the interpretation of Cold War origins’, Perspectives in American History, IV (1970), 313–47Google Scholar; Richardson, J. L., ‘Cold War revisionism: a critique’, World Politics, XXIV, 4 (1972), 579–612CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

5 Gaddis, John L., The United States and the origins of the Cold War, 1941–1947 (New York, 1972)Google Scholar. For useful historiographical surveys see Smith, Geoffrey, ‘”Harry, we hardly knew you”: revisionism, politics and diplomacy, 1945–54’, American Political Science Review, LXX, 2 (1976), 560–82CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Walker, J.Samuel, ‘Historians and Cold War origins: the new consensus’, in Haines, Gerald K. and Walker, J. Samuel (eds.), American foreign relations: a historiographical review (Westport, Connecticut, 1981), pp. 207–36Google Scholar; Gaddis, John L., ‘The emerging post-revisionist synthesis and the origins of the Cold War’, Diplomatic History, VII, 3 (1983), 171–90CrossRefGoogle Scholar. For detailed bibliographic guidance see Burns, Richard D. (ed.), Guide to American foreign relations since 1700 (Santa Barbara, California, 1983)Google Scholar.

6 Walker, , ‘Historians and cold war origins’, 228Google Scholar.

7 Gaddis, , ‘Emerging post-revisionist synthesis’, 172Google Scholar; McCormick, Thomas J., ‘Drift or mastery?: a corporatist synthesis for American diplomatic history’, Reviews in American History, X, 4 (1982), 319Google Scholar. See also the debate following Gaddis's article, pp. 191–204.

8 Gaddis, John L., Strategies of containment: a critical appraisal of post-war American national security policy (New York, (1982)Google Scholar; Paterson, Thomas G., On every front: the making of the Cold War (New York, 1979)Google Scholar.

9 Gaddis, , ‘Emerging post-revisionist synthesis’, 171Google Scholar.

10 E.g. DePorte, A. W., Europe between the superpowers: the enduring balance (New Haven, 1979)Google Scholar.

11 de Tocqueville, Alexis, Democracy in America, ed. Mayer, J. P. (New York, 1969), 1, 412–13Google Scholar; Seeley, J. R., The expansion of England (London, 1884), pp. 16, 287–8, 298–301Google Scholar.

12 Quoted in Yergin, Daniel, Shattered peace: the origins of the Cold War and the national security state (London, 1978), 223Google Scholar.

13 For an account suggesting parallels between the two periods see Maier, Charles S., ‘The two post-war eras and the conditions for stability in twentieth-century western Europe’, American Historical Review, LXXXVI, 2 (1981), 327–52CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and following discussion, 353–67.

14 See Niethammer, Lutz, ‘Structural reform and a compact for growth: conditions for a united labor union movement in western Europe after the collapse of fascism’, in Maier, Charles S. (ed.), The origins ofthe Cold War and contemporary Europe (New York, 1978), pp. 201–43Google Scholar.

15 Kimball, Warren F., Swords or ploughshares?: the Morgenthau plan for defeated Mali Germany, 1943–1946 (Philadelphia, 1976)Google Scholar. Roosevelt told this story ofhis German schooidays: ‘When I was eleven in 1893, I think it was, my class was started on the study of “Heimatkunde” – geography lessons about the village, then about how to get to the neighbouring towns and what one would see, and, finally, on how to get all over the Province of Hesse-Darmstadt. The following year we were taught all about roads and what we would see on the way to the French border. I did not take it the third year but I understand the class was “conducted” to France – all roads leading to Paris.’ (Roosevelt to Arthur Murray, 04 March 1940, Elibank papers, National Library of Scotland, Edinburgh, MS. 8809, fo. 229.)

16 ‘Record of conversation at luncheon at the British Embassy’, Washington, on 22nd March 1943’. P. 3. w p (43) 233. Cabinet Office papers, CAB 66/37 (Public Record Office, Kew). For fuller discussion of Churchill's attitudes see Reynolds, David, ‘Churchill, the “special relationship” and the debate about post-war European security, 1940–1945’, American Historical Association Proceedings, 1983, (Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1984)Google Scholar.

17 On British policy see Barker, Elisabeth, Churchill and Eden at war (London, 1978)Google Scholar, and Rothwell, Victor, Britain and the Cold War, 1941–1947. (London, 1982)Google Scholar – mainly about the Foreign Office. My account of U.S. policy, minimizing the differences between Roosevelt and Churchill, adraws on Mark, Eduard, ‘American policy toward eastern Europe and the origins of the Cold War, 1941–1946: an alternative interpretation’, Journal of American History, LXVIII, 2 (1981), 313–36CrossRefGoogle Scholar. The texts of the ‘percentages agreement’ discussions are printed in Siracusa, Joseph M., ‘The meaning of TOLSTOY: Churchill, Stalin and the Balkans, Moscow, October 1944’ Diplomatic History, 111, 4 (1979), 443–63CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

18 Anderson, , United States, Great Britain, p. 152Google Scholar; Sherry, Michael S., Preparing for the next war: American plans for post-war defense, 1941–1945 (New Haven, 1977), 204Google Scholar.

19 Herring, George C., Aid to Russia, 1941–1946: strategy, diplomacy, the origins of the Cold War (New York, 1973)Google Scholar.

20 Roosevelt to Assistant Secretary of State, 21 Feb. 1944, State Department decimal file, 740.00119 Control (Germany), /2–2144, RG 59, National Archives, Washington, D.C.

21 See also Hathaway, Robert M., Ambiguous partnership: Britain and America, 1944–1947 (New York, 1981)Google Scholar; Boyle, Peter G., ‘The British Foreign Office view of Soviet-American relations, 1945–1946’, Diplomatic History, III, 3 (1979), 307–20CrossRefGoogle Scholar, and ‘The British Foreign Office and American foreign policy, 1947–;48’, Journal of American Studies, XVI, 3 (1982), 373Google Scholar.–89; Ovendale, R., ‘Britain, the U.S.A. and the European Cold War, 1945–;48’, History, LXVII (1982), 217–36CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

22 Dalton, Hugh, diary, XXXII, 28, 23 02 1945Google Scholar (British Library of Political and Economic Science, London, quoted by permission of the Librarian).

23 May, Ernest R., ‘Lessons’ of the past: the use and misuse of history in American foreign policy (New York, 1973)Google Scholar; Adler, Les K. and Paterson, Thomas G., ‘Red fascism: the merger of Nazi Germany and Soviet Russia in the American image of totalitarianism, 1930's to 1950’, American Historical Review, LXXV, 4 (1970), 1046–4CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

24 Kuniholm, Bruce R., The origins of the Cold War in the Near East: great power conflict and diplomacy in Iran, Turkey, and Greece (Princeton, 1980)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Iatrides, John O. (ed.), Greece in the 1940s: a nation in crisis (Hanover, New Hampshire, 1981)Google Scholar; Wittncr, Lawrence S., American intervention in Greece, 1943–;1949 (New York, 1982)Google Scholar.

25 Alexander has no doubt (e.g. pp. 7–;8) that the Greek communists, (the K K E) aimed ultimately at a ‘Bolshevist Greece’, to be achieved via a multi-party government under communist leadership. His views need to be compared with those of other scholars such as Heinz Richter and John Iatrides, who portray the KKE as far less certain and single-minded (see their essays in Iatrides, ed., Greece in the 1940s).

26 See Wittner, American intervention, ch. 3; Paterson, Thomas G., ‘Presidential foreign policy, public opinion, and Congress: the Truman years’, Diplomatic History, III 1 (1979), 1–;18.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

27 Jenkins, Roy, Nine men of power (London, 1974), p. 77.Google Scholar

28 For a useful summary, synthesizing various approaches, see Jackson, Scott, ‘Prologue to the Marshall plan: the origins of the American commitment for a European recovery program’, Journal of American History, LXV, 4 (1979), 1043–;68CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Recent studies of U.S. and British policy in Germany include Gimbel, John, The origins of the Marshall plan (Stanford, California, 1976)Google Scholar; Backer, John H., The decision to divide Germany (Durham, North Carolina, 1978)Google Scholar; Rostow, W. W., The division of Europe after World War II, 1946 (Austin, Texas, 1982)Google Scholar; Steinginger, Rolf, ‘Reform und Realität. Ruhrfrage und Sozialisierung in der anglo-amerikanischen Deutschlandpolitik, 1947/48’, Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte, XXVII, 2 (1979), 167–;240Google Scholar; and the essays in Scharf, Claus and Schröder, Hans-Jürgen (eds.), Die Deutschlandpolitik Grossbritanniens und die Britische Zone, 1945–;1949 (Wiesbaden, 1979)Google Scholar. In an important book, published after the completion of this essay, Alan Milward questions the extent of the economic crisis of 1947. Milward, Alan S., The reconstruction of Western Europe, 1945–;1951 (London, 1984)Google Scholar.

29 Clarke, Peter, ‘High tide for the left’, Times Literary Supplement (16 03 1984), p. 264.Google Scholar

30 Moore, Ben T. to Wilcox, Clair, 28 July 1947, in U.S.A., Department of State, Foreign relations of the United States, 1947, III, 239 (Washington, D.C., 1972).Google Scholar

31 For other accounts stressing the British role in events of this period see SirHenderson, Nicholas, The birth of NATO (London, 1982)Google Scholar and Shlaim, Avi, ‘Britain, the Berlin blockade and the Cold War’, International Affairs, LX, 1 (1983–;1984), 1–;14CrossRefGoogle Scholar. See also Barker, Elisabeth, The British between the superpowers, 1945–;1950 (London, 1984)Google Scholar.

32 Bullock claims, for instance, that Bevin's response to Marshall's speech was entirely his own initiative, without guidance from the Americans or the British Embassy in Washington (pp. 404–;5). But see Alan Milward's comments, based on documents in the British Treasury files, that ‘Bevin's apparently dramatic response to the news of Marshall's speech was considered, expected, and in accordance…with relatively specific hints that Washington would like to see as an immediate response the formation of some sort of European organization which would co-operate with whatever American organization would administer the aid programme.’ Milward, in Lipgens, Walter, A history of European integration, I, 1945–;1947 (Oxford, 1982), p. 507Google Scholar. For fuller discussions of the U.S. role in these events see e.g. Kaplan, Lawrence S., ‘Toward the Brussels pact’, Prologue, XII, 2 (1980)Google Scholar; Henrikson, Alan K., ‘The creation of the North Atlantic alliance, 1948–;1952’, US Naval War College Review XXXII (1980), 4–;39Google Scholar; Wiebes, Cees and Zeeman, Bert, ‘The Pentagon negotiations, March 1948: the launching of the North Atlantic Treaty’, International Affairs, LXIX, 3 (1983), 351–;63CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

33 U.S.A., Department of State, A decade of American foreign policy: basic documents, 1941–;1949 (Washington, D.C., 1950), p. 1329Google Scholar. Bullock, p. 645, prints the draft and says that this was the version the U.S.A. signed (though he does print the final text on p. 671).

34 See SirFursdon, Edward, The European Defence Community: a history (London, 1980).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

35 E.g. Hassner, Pierre, ‘Recurrent strains, resilient structures’, in Tucker, Robert W. and Wrigley, Linda (eds.), The Atlantic alliance and its critics (New York, 1983), pp. 61–;94Google Scholar; Joffe, Josef, ‘Can Europe live with its defence?’ in Freedman, Lawrence (ed.), The troubled alliance: Atlantic relations in the 1980s (London, 1983), pp. 133–;4Google Scholar.

36 On integrationist ideas in general see Vaughan, Richard, Twentieth century Europe: paths to unity (London, 1979)Google Scholar; and for more detail Lipgens, History, cited above, note 32.

37 On French and German policy in this period see Grosser, Alfred, La quatrième république et sa politique extérieure (Paris, 3rd edn, 1972)Google Scholar; the useful chapter in Harrison, Michael M., The reluctant ally: France and Atlantic security (Baltimore, 1981)Google Scholar; Foerster, Roland G. et al. , Anfänge westdeutscher Sicherheitspolitik, 1945–;1956. I: Von der Kapitulation bis zum Pleven-Plan (Munich, 1982)Google Scholar.

38 Cf. Baylis, John, ‘Britain and the Dunkirk treaty: the origins of NATO’, Journal of Strategic Studies, v, 2 (1982), 236–;47CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Young, John W., ‘The Labour government's policy towards France, 1945–;1951’, Cambridge University Ph.D. dissertation, 1983Google Scholar; Warner, Geoffrey, ‘The Labour governments and the unity of western Europe, 1945–;51’ in Ovendale, Ritchie (ed.), The foreign policy of the British Labour government, 1945–;51 (Leicester, 1984), pp. 61–;82Google Scholar.

39 See Lipgens, History; also Rappaport, Armin, ‘The United States and European integration: the first phase’, Diplomatic History, V, 2 (1981), 121–;49CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Hogan, Michael J., ‘The search for a “creative peace”: the United States, European unity, and the origins of the Marshall plan’, Diplomatic History, VI, 3 (1982), 267–;85CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

40 ‘Turn of the wheel’ in Sandburg, Carl, Complete poems (New York, 1950), p. 645.Google Scholar

41 Quoted in Foot, Peter, ‘Defence burden-sharing in the Atlantic community, 1945–1954’, Aberdeen studies in defence economics, XX (1981), 13.Google Scholar

42 Henrikson, , ‘Creation of the North Atlantic alliance’, p. 38 n. 103.Google Scholar

43 Lundestad, Geir, America, Scandinavia, and the Cold War, 1945–;1949 (Oslo, 1980), p. 333.Google Scholar

44 Resis, Albert, ‘The Churchill-Stalin secret “percentages” agreement on the Balkans, Moscow, October 1944’, American Historical Review, LXXXIII, 2 (1978), 368–;87CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and ‘Spheres of influence in Soviet wartime diplomacy’, Journal of Modern History, LIII, 3 (1981), 417–;39Google Scholar.

45 Mastny, Vojtech, Russia's road to the Cold War: diplomacy, warfare, and the politics of communism, 1941–;1945 (New York, 1979), esp. pp. 41, 282–;3.Google Scholar

46 Nogee, Joseph L. and Donaldson, Robert H., in their useful survey Soviet foreign policy since World War II (Oxford, 1981), pp. 65–;6Google Scholar, call Stalin's handling of the Marshall Plan ‘a blunder of major proportions that had a profound effect on the future of European politics’. Participation by the U.S.S.R. and its clients, they suggest, could have relieved the economic burden on Moscow or, more likely, at least made the Plan politically unacceptable in the U.S.A.

47 For a similar verdict see Ulam, Adam B., Expansion and coexistence: Soviet foreign policy, 1917–;73 (2nd edn, New York, 1974), p. 404.Google Scholar

48 McCagg, William O. Jr, Stalin embattled, 1943–;1948 (Detroit, 1978).Google Scholar

49 Papp, N. G., ‘The democratic struggle for power in Hungary: party strategies, 1945–;46’, East Central Europe, VI, 1 (1979), 1–;19CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Myant, Martin R., Socialism and democracy in Czechoslovakia, 1945–;1948 (Cambridge, 1981)CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Sandford, Gregory W., From Hitler to Ulbricht: the communist reconstruction of East Germany, 1945–;1946 (Princeton, 1983)Google Scholar.

50 Okey, Robin, Eastern Europe, 1740–;1980: feudalism to communism (London, 1982) pp. 196–;7CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Seton-Watson, Hugh, The East European revolution (London, 1950)Google Scholar, remains the classic account. See also the useful essays in McCauley, Martin (ed.), Communist power in Europe, 1944–;1949 (London, 1977)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

51 Djilas, Milovan, Conversations with Stalin, tr. by Petrovich, Michael B. (London, 1962), p. 105.Google Scholar

- 10

- Cited by