1. Introduction

Since 2017, the 10 new insights in climate science (hereafter 10NICS) annually summarize a set of the most critical aspects of Earth's complex climate system – including physical, biogeochemical and socioeconomic/sociocultural dimensions. Staying well below 2 °C of global warming above preindustrial temperatures and aiming to not exceed 1.5 °C are the principal goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement. These thresholds have since been reinforced by a number of large-scale science assessments (IPCC, 2018, 2019b, 2019a, 2021; Pörtner et al., Reference Pörtner, Scholes, Agard, Archer, Arneth, Bai, Barnes, Burrows, Chan, Cheung, Diamond, Donatti, Duarte, Eisenhauer, Foden, Gasalla, Handa, Hickler, Hoegh-Guldberg and Ngo2021). The new insights presented here, based on scientific literature since January 2020, emphasize the urgent need for meaningful mitigation and adaptation.

The 10NICS topics are not intended to form a comprehensive scientific assessment. Intentionally limited to 10, each insight is succinct and does not try to cover entire fields. The 10NICS are presented in (a) an academic article for a scholarly audience (this publication) and (b) a policy report for policymakers and the general public.

Here we detail the methods used for the selection of the 10 insight topics, and then give a concise summary of each insight, briefly setting the background, elaborating on some recent developments in the field, and putting the new research insights into context with climate change scenarios or climate policies. In the concluding section, we develop and discuss a wider-scope scientific synthesis of the 10 insights.

2. Methodology

Each year the three hosts of the 10NICS – Future Earth, the Earth League and the World Climate Research Programme (WCRP) – invite the global science community to submit their proposals for new climate science insights in an open call. To qualify as a candidate topic, the proposals are required to be based on at least two to three peer-reviewed publications since January of the preceding year. The three hosts select an editorial board, which oversees the overall scientific quality and coherence of the output (academic article and policy report).

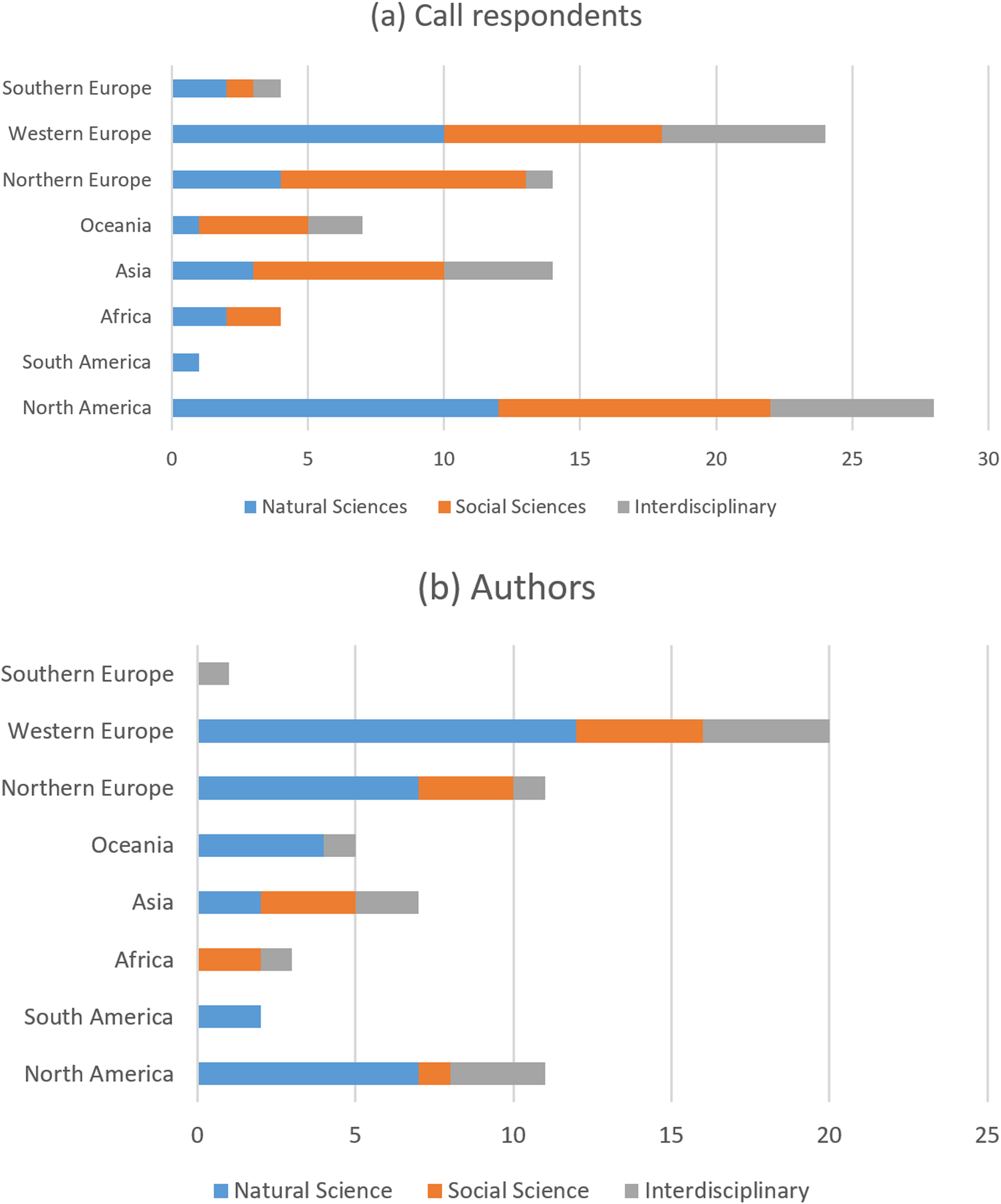

The 2021 call for topics was broadly and globally distributed via different channels (such as websites, social media accounts or mailing lists associated with the hosts and connected institutions, as well as via individual invitations), directly reaching over 8500 people. In total, 96 people responded to the call (Figure 1(a)). The 168 suggested topics (underpinned by 425 references, 332 of which qualified as recent from 2020/2021) were sorted and merged into 27 candidate insights. The editorial board extracted a list of 10 NICS from the 27 candidates.

Figure 1. Classification of (a) call respondents and (b) authors (including invited experts, coordinating authors and editorial board members) in terms of scientific discipline and geography (affiliation based, for details about the geography definitions, see Supplement material). Gender composition among call respondents was 37/59 (female/male); among authors it was 31/31. The call respondents' classification was made based on their responses; the authors' classification was individually confirmed.

Each insight was written by a team of three to five experts and one coordinating author. The experts were selected for each insight according to their discipline and scientific reputation, with the goal of promoting diversity in terms of gender, geography and scientific discipline (Figure 1(b)). The coordinating authors were staff appointed by the hosts.

3. New insights

3.1 Insight 1: Can global warming still be kept to 1.5 °C, and if yes, how?

The Paris Agreement aims to hold global warming to well below 2 °C and to pursue limiting it to 1.5 °C. As of 2020, human-caused global temperature increase had reached 1.2 °C above 1850–1900 levels (Reference Wunderling, Donges, Kurths and Winkelmannwww.globalwarmingindex.org). Due to natural variability, an individual year's temperature statistically may exceed 1.5 °C within the next five years (World Meteorological Organization, 2021). But warming in a single year is not how to assess whether limits set by the Paris Agreement are met as they refer to long-term, global averages (Rogelj et al., Reference Rogelj, Schleussner and Hare2017).

Updates in historical temperature datasets now estimate about 0.1 °C higher historical warming as a result of improved interpretation of temperature observations from the early-industrial period (Kadow et al., Reference Kadow, Hall and Ulbrich2020; Morice et al., Reference Morice, Kennedy, Rayner, Winn, Hogan, Killick, Dunn, Osborn, Jones and Simpson2021; Rohde & Hausfather, Reference Rohde and Hausfather2020; Vose et al., Reference Vose, Huang, Yin, Arndt, Easterling, Lawrimore, Menne, Sanchez-Lugo and Zhang2021). Targeting 1.5 °C of warming above 1850–1900 levels using these updated temperature datasets therefore results in a shorter temperature distance between today and 1.5 °C, and thus a lower remaining carbon budget than implied at the time of the Paris Agreement.

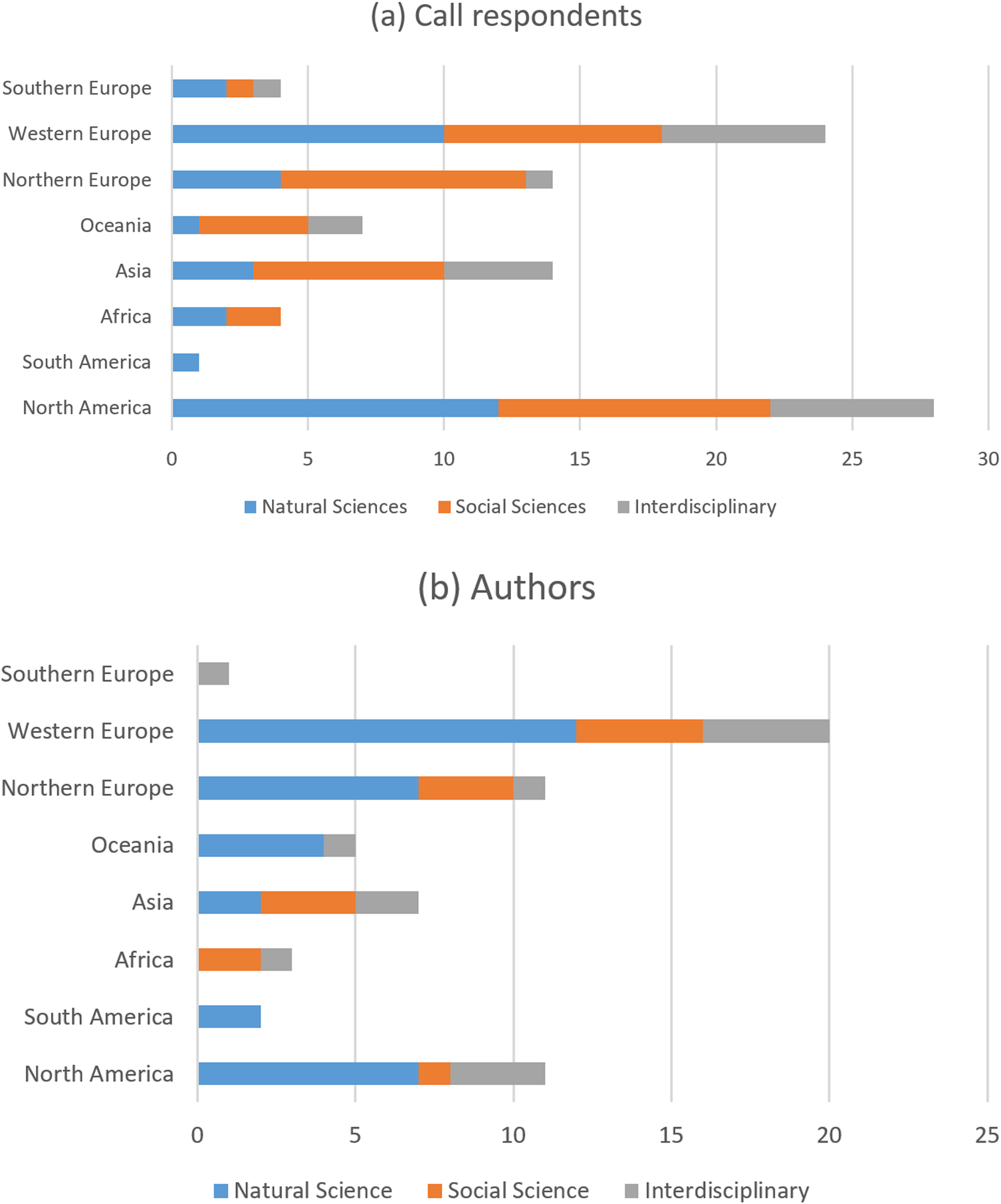

A new uncertainty analysis (using this updated estimate of historical warming) concluded that in order to have even odds of not exceeding 1.5 °C, the atmospheric carbon uptake would have to be capped at 440 GtCO2 from 2020 onwards (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Tokarska, Rogelj, Smith, MacDougall, Haustein, Mengis, Sippel, Forster and Knutti2021). The associated remaining carbon budget estimate applies to total future emissions until net-zero CO2 emissions are achieved, given the current understanding of climate sensitivity and carbon cycle responses to a typical 1.5 °C-compatible emission scenario (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Tokarska, Nicholls, Rogelj, Canadell, Friedlingstein, Thomas, Frölicher, Forster, Gillett, Ilyina, Jackson, Jones, Koven, Knutti, MacDougall, Meinshausen, Mengis, Séférian and Zickfeld2020, Reference Matthews, Tokarska, Rogelj, Smith, MacDougall, Haustein, Mengis, Sippel, Forster and Knutti2021) (Figure 2). If at that point CO2 emissions remain at net-zero, warming could remain largely stable (MacDougall et al., Reference MacDougall, Frölicher, Jones, Rogelj, DamonMatthews, Zickfeld, Arora, Barrett, Brovkin, Burger, Eby, Eliseev, Hajima, Holden, Jeltsch-Thömmes, Koven, Mengis, Menviel, Michou and Ziehn2020). However, this carbon budget estimate is contingent on concomitant stringent and unprecedented reductions in non-CO2 emissions such as methane from agriculture (Rogelj et al., Reference Rogelj, Forster, Kriegler, Smith and Séférian2019), land use changes, and on intact natural carbon sinks and stores, among other assumptions. Recent literature suggests that many of these assumptions may be overly optimistic (Leahy et al., Reference Leahy, Clark and Reisinger2020).

Figure 2. Heading towards net-zero CO2 emissions and the 1.5 °C target. The x-axis shows cumulative CO2 emissions from 2020 until net-zero emissions are reached, with the associated likelihood of limiting peak warming to 1.5 °C on the left y-axis (based on the distribution of the 1.5 °C remaining carbon budget from Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Tokarska, Rogelj, Smith, MacDougall, Haustein, Mengis, Sippel, Forster and Knutti2021). The right y-axis marks the year that net-zero CO2 emissions would be reached assuming a constant linear decrease from 2020 onwards, with the colours indicating the associated annual emissions decrease. Even odds limiting warming to 1.5 °C would require cumulative emissions of 440 GtCO2 from 2020 onwards and require annual emission reductions of 2 GtCO2/year.

At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound effect on global CO2 emissions. In the year 2020, global CO2 emissions decreased by about 7% compared with 2019 (Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Sitch, Le Quéré, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin, Aragão, Arneth, Arora, Bates and Zaehle2020). A single-year reduction has only negligible long-term effects (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Forster, Evans, Gidden, Jones, Keller, Robin, Lamboll, Le Quéré, Rogelj, Rosen, Schleussner, Richardson, Smith and Turnock2020), but sustaining a similar level of annual decrease (2 GtCO2/year or 5% of 2019 emissions), would bring us to net-zero around 2040, in line with about even odds of limiting warming to 1.5 °C (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Tokarska, Rogelj, Smith, MacDougall, Haustein, Mengis, Sippel, Forster and Knutti2021).

The emissions reductions due to COVID-19 were largely because of changes in demand, while the structure of the economy remained unchanged. However, structural reductions in carbon intensity have been shown to multiply the effect of small demand reductions (Bertram et al., Reference Bertram, Luderer, Creutzig, Bauer, Ueckerdt, Malik and Edenhofer2021). Furthermore, continued progress in solar and wind energy technologies suggests that additional low-carbon generation might soon be sufficient to meet new power demand (Whiteman et al., Reference Whiteman, Akande, Elhassan, Escamilla, Lebedys and Arkhipova2021) if deployed in conjunction with demand-side reductions (see Insight 6). If policies and recovery investments are aligned with efficiency and low-carbon energy technologies (Pianta et al., Reference Pianta, Brutschin, van Ruijven and Bosetti2021), the needed drastic structural emissions reductions could be achieved.

Studies of deep decarbonization pathways show that the power sector offers many opportunities for deep decarbonization by the middle of the century, including in China (Duan et al., Reference Duan, Zhou, Jiang, Bertram, Harmsen, Kriegler, van Vuuren, Wang, Fujimori, Tavoni, Ming, Keramidas, Iyer and Edmonds2021), making electrification vital (Victoria et al., Reference Victoria, Zhu, Brown, Andresen and Greiner2020). Direct electrification is preferable as it increases efficiency (Madeddu et al., Reference Madeddu, Ueckerdt, Pehl, Peterseim, Lord, Kumar, Krürger and Luderer2020), but hydrogen-based fuels could play a role where electrification is not feasible (Ueckerdt et al., Reference Ueckerdt, Bauer, Dirnaichner, Everall, Sacchi and Luderer2021).

The deep and immediate emissions reductions required to keep warming to 1.5 °C indicate that all mitigation levers need to be employed at their most ambitious scales (IEA, 2021; IPCC, 2018; Warszawski et al., Reference Warszawski, Kriegler, Lenton, Gaffney, Jacob, Klingenfeld, Koide, Costa, Messner, Nakicenovic, Schellnhuber, Schlosser, Takeuchi, Van Der Leeuw, Whiteman and Rockström2021). Residual emissions from existing and proposed infrastructures will very likely exceed the remaining carbon budget for 1.5 °C (Tong et al., Reference Tong, Zhang, Zheng, Caldeira, Shearer, Hong, Qin and Davis2019), necessitating either the early retirement of economically viable infrastructure, or the large-scale deployment of carbon removal options. If near-term emissions are not sufficiently reduced, the window of opportunity to limit peak warming to 1.5 °C will close. Net negative emissions could return temperatures below this threshold after an overshoot (Tokarska et al., Reference Tokarska, Schleussner, Rogelj, Stolpe, Matthews, Pfleiderer and Gillett2019), but this would require huge economic effort and strong regulations (Strefler et al., Reference Strefler, Kriegler, Bauer, Luderer, Pietzcker, Giannousakis and Edenhofer2021) as well as potentially crossing critical tipping points (see Insight 4). Broad portfolios of different carbon removal options could potentially increase total removal, while limiting the excessive use of individual options and their associated negative side effects (Fuhrman et al., Reference Fuhrman, McJeon, Patel, Doney, Shobe and Clarens2020; Strefler et al., Reference Strefler, Kriegler, Bauer, Luderer, Pietzcker, Giannousakis and Edenhofer2021).

3.2 Insight 2: impact of non-CO2 factors on global warming

Climate warming is driven by human activities that produce both positive and negative climate forcing. About 46% of current climate warming (21% of net warming) is caused by factors other than carbon dioxide (CO2) that include greenhouse gases, their precursors or warming aerosols such as black carbon (IPCC, 2021, table AIII.3). Cooling factors, such as sulphate and nitrate aerosols and albedo changes due to land-use change, offset 20–50% of anthropogenic warming. These ‘non-CO2 factors’ are the largest source of uncertainty in the remaining carbon budget (IPCC, 2018, Chapter 2).

The net impact of non-CO2 factors has increased from zero to an increasing warming effect over the past 20 years (Mengis & Matthews, Reference Mengis and Matthews2020), linked to both increasing methane and nitrous oxide emissions from agricultural and land-use activities, and reductions in aerosol emissions.

Substantial progress in our understanding of aerosol radiative forcing provides higher confidence in the significant cooling effect of aerosols from human activities since 1850 (two chances out of three for a 0.6–1.6 W/m2 cooling) (Bellouin et al., Reference Bellouin, Quaas, Gryspeerdt, Kinne, Stier, Watson-Parris, Boucher, Carslaw, Christensen, Daniau, Dufresne, Feingold, Fiedler, Forster, Gettelman, Haywood, Lohmann, Malavelle, Mauritsen and Stevens2020), dominated by aerosol interactions with clouds.

The COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns in 2020 were an unintended experiment illustrating the impact of reductions in aerosol and other short-term climate-forcing agents. Aerosol emissions from fossil fuel combustion, especially from the transport sector, reduced dramatically and increased global mean temperatures by 0.03 °C within a few months, with regional effects as high as 0.3 °C in May 2020 (Gettelman et al., Reference Gettelman, Lamboll, Bardeen, Forster and Watson-Parris2021). Aerosol reductions had a larger effect than reductions in CO2, ozone or aeroplane contrails on timescales of months to a year; however, the combined effects of the 2020/2021 reductions in greenhouse gases and aerosols on temperature become negligible in the long term (Forster et al., Reference Forster, Forster, Evans, Gidden, Jones, Keller, Robin, Lamboll, Le Quéré, Rogelj, Rosen, Schleussner, Richardson, Smith and Turnock2020).

Methane (CH4) atmospheric concentrations continue to increase rapidly with a record high in 2020, reaching concentrations 6% higher than in 2000 (NOAA (AGGI), 2021). Increasing anthropogenic emissions over the last two decades are likely the dominant cause, with agriculture and waste sectors contributing in southern and South-eastern Asia, South America and Africa, and fossil fuel sectors contributing in China and the United States (Jackson et al., Reference Jackson, Saunois, Bousquet, Canadell, Poulter, Stavert, Bergamaschi, Niwa, Segers and Tsuruta2020; Saunois et al., Reference Saunois, Stavert, Poulter, Bousquet, Canadell, Jackson, Raymond, Dlugokencky, Houweling, Patra, Ciais, Arora, Bastviken, Bergamaschi, Blake, Brailsford, Bruhwiler, Carlson, Noce and Zhuang2020).

Methane represents one of the greatest opportunities to address climate change. Readily available measures could reduce more than 45% of projected anthropogenic methane emissions by 2030. Low-cost reductions by reducing fossil fuel leaks and waste treatment would deliver about 0.3 °C of avoided warming by the 2040s (UNEP, 2021).

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is accumulating in the atmosphere at an increasing rate, with global emissions 10% greater in 2016 than in the 1980s, faster than all scenarios used by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). The use of nitrogen fertilizers in agriculture, including organic fertilizer from livestock manure, caused over 70% of global N2O emissions in the recent decade (2007–2016) with the largest growth coming from emerging economies, particularly Brazil, China and India (Tian et al., Reference Tian, Xu, Canadell, Thompson, Winiwarter, Suntharalingam, Davidson, Ciais, Jackson, Janssens-Maenhout, Prather, Regnier, Pan, Pan, Peters, Shi, Tubiello, Zaehle, Zhou and Yao2020).

Growing demand for food and animal feed will further increase global N2O and CH4 emissions (NOAA (AGGI), 2021; Tian et al., Reference Tian, Xu, Canadell, Thompson, Winiwarter, Suntharalingam, Davidson, Ciais, Jackson, Janssens-Maenhout, Prather, Regnier, Pan, Pan, Peters, Shi, Tubiello, Zaehle, Zhou and Yao2020; Yao et al., Reference Yao, Tian, Shi, Pan, Xu, Pan and Canadell2020). Some mitigation options in the agriculture sector are available for immediate deployment, including increasing the efficiency of nitrogen use, promoting lower meat consumption and reducing food waste. Many of these mitigation actions will also improve water and air quality, benefiting both human health and ecosystems.

Anthropogenic climate-forcing factors can be partitioned into land-use and agricultural activities, and fossil fuel combustion activities (Figure 3). Non-CO2 factors from land-use and agricultural activities produce a net positive forcing, whilst from fossil fuel combustion they generate a net negative forcing (Mengis & Matthews, Reference Mengis and Matthews2020). This has important implications: future reductions in fossil fuel combustion as well as air quality improvements will eliminate a large part of the negative forcing from co-emitted aerosols. At the same time, the positive forcing from land-use and agricultural activities is likely to increase with the projected increase in food demand in most scenarios (IPCC, 2018, Chapter 2). These two effects could lead to a substantial increase in non-CO2 climate forcing (Mengis & Matthews, Reference Mengis and Matthews2020). The aerosol effects are accounted for in most scenarios; the land-use changes are often not (Rogelj et al., Reference Rogelj, Popp, Calvin, Luderer, Emmerling, Gernaat, Fujimori, Strefler, Hasegawa, Marangoni, Krey, Kriegler, Riahi, Van Vuuren, Doelman, Drouet, Edmonds, Fricko, Harmsen and Tavoni2018). If non-CO2 greenhouse gases continue to increase, this will reduce the remaining carbon budget as it will cause continuous climate warming (Mengis & Matthews, Reference Mengis and Matthews2020). Opportunities to mitigate non-CO2 greenhouse gases need to be developed and adopted.

Figure 3. Current anthropogenic climate forcing (based on IPCC AR5 datasets) partitioned based on their respective sources of emissions contributions from land-use and agricultural activities (left) and fossil fuel combustion activities (right). The partitioning for the non-CO2 greenhouse gas-forcing factors has been done based on Mengis and Matthews (Reference Mengis and Matthews2020); the partitioning of CO2 is based on cumulative emissions of 395 gigatonnes of carbon (GtC) and 200 GtC (FFC and LUC, respectively) between 1850 and 2014 from Friedlingstein et al., Reference Friedlingstein, O'Sullivan, Jones, Andrew, Hauck, Olsen, Peters, Peters, Pongratz, Sitch, Le Quéré, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Alin, Aragão, Arneth, Arora, Bates and Zaehle2020. Uncertainty whiskers to the right of the bars show forcing uncertainties of the respective contributions as reported by AR5. CO2, carbon dioxide; N2O, nitrous oxide; CH4, methane; tr. O3, tropospheric ozone; BC, black carbon aerosol from fossil fuel and biofuel; OC, primary and secondary organic aerosols; SOx, sulphate aerosols; NOx, nitrogen oxides; LUC, land-use changes.

3.3 Insight 3: climate change forces fire extremes to reach new dimension with drastic impacts

Wildfires are an intrinsic feature of many ecosystems around the world, but new scientific advances are showing that human-induced climate change is intensifying fire regimes. There has been an increase in fire extent, intensity and the duration of the fire season, and a change in the quality and quantity of the fuel and frequency of fires.

Recently, formal attribution studies of fire conditions have been produced with higher confidence due to two reasons: the methods and practices for this study continue to evolve and gain rigour (e.g. Swain et al., Reference Swain, Singh, Touma and Diffenbaugh2020), and significant fire and megafire events have more clearly contained a human fingerprint (e.g. Abram et al., Reference Abram, Henley, Sen Gupta, Lippmann, Clarke, Dowdy, Sharples, Nolan, Zhang, Wooster, Wurtzel, Meissner, Pitman, Ukkola, Murphy, Tapper and Boer2021). These studies focus on fire weather (hot, dry, windy conditions), ignition sources (dry lightning events) and seasonal climate conditions that precondition the landscape for fire. Evidence for human influence is found in fire seasons of unprecedented magnitude in the modern era in regions as diverse as California (Goss et al., Reference Goss, Swain, Abatzoglou, Sarhadi, Kolden, Williams and Diffenbaugh2020), the Mediterranean basin (e.g. Ruffault et al., Reference Ruffault, Curt, Moron, Trigo, Mouillot, Koutsias, Pimont, Martin-StPaul, Barbero, Dupuy, Russo and Belhadj-Khedher2020), Canada (Kirchmeier-Young et al., Reference Kirchmeier-Young, Wan, Zhang and Seneviratne2019), the Arctic and Siberia (McCarty et al., Reference McCarty, Smith and Turetsky2020) and Chile (Bowman et al., Reference Bowman, Moreira-Munoz, Kolden, Chavez, Munoz, Salinas, Gonzalez-Reyes, Rocco, de La Barrera, Williamson, Borchers, Cifuentes, Abatzoglou and Johnston2019). Assessments of this attribution can now assign at least medium confidence to human influence not only on trends in fire weather but also on fire events (e.g. van Oldenborgh et al., Reference van Oldenborgh, Krikken, Lewis, Leach, Lehner, Saunders, van Weele, Haustein, Li, Wallom, Sparrow, Arrighi, Singh, van Aalst, Philip, Vautard and Otto2021). The extreme heatwave that preconditioned western North America for wildfires in summer 2021 undoubtedly was more likely and more severe due to climate change (world weather attribution).

Megafires produce large carbon and aerosol emissions, for example, the 2019–20 Australian fires produced pyrocumulonimbus smoke plumes that circumnavigated the globe (Kablick et al., Reference Kablick, Allen, Fromm and Nedoluha2020) and emitted approximately between 670 (310–1030) (Bowman et al., Reference Bowman, Williamson, Price, Ndalila and Bradstock2021) and 715 (517–876) Mt CO2 in total (van der Velde et al., Reference van der Velde, van der Werf, Houweling, Maasakkers, Borsdorff, Landgraf, Tol, van Kempen, van Hees, Hoogeveen, Veefkind and Aben2021). These megafires affected entire biomes in southern and eastern Australia with unprecedented impacts on flora and fauna (Gallagher et al., Reference Gallagher, Allen, Mackenzie, Yates, Gosper, Keith, Merow, White, Wenk, Maitner, He, Adams and Auld2021; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Tulloch, Radford, Williams, Reside, Macdonald, Mayfield, Maron, Possingham, Vine, O'Connor, Massingham, Greenville, Woinarski, Garnett, Lintermans, Scheele, Carwardine, Nimmo and Watson2020), including those that usually tolerate fire, threatening the fire-sensitive World Heritage-listed Gondwana rainforests (Nolan et al., Reference Nolan, Boer, Collins, Resco de Dios, Clarke, Jenkins, Kenny and Bradstock2020). In the Arctic circle and Siberia, amplification of arctic temperatures and dry lightning caused large areas to burn, affecting Arctic tundra, bogs, fens and marshes (McCarty et al., Reference McCarty, Smith and Turetsky2020). They released about 175 MtCO2 in 2019 and nearly 250 MtCO2 in 2020, while in California and Oregon, wildfires led to an excess carbon of at least 30 MtCO2 in a single year. In the world's largest wetland, the Brazilian Pantanal, extreme drying permitted a fivefold increase in burned areas, with emissions of 524 tonnes of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) and 115 MtCO2 to the atmosphere (Copernicus Atmosphere Monitoring Service (CAMS), ECMWF 2021). Regeneration of affected biomes is at risk given the high number of negatively affected species, including many endemics, and there are unclear prospects of vegetation regrowth to recover lost carbon stocks (Bowman et al., Reference Bowman, Williamson, Price, Ndalila and Bradstock2021; Nolan et al., Reference Nolan, Boer, Collins, Resco de Dios, Clarke, Jenkins, Kenny and Bradstock2020; Pickrell & Pennisi, Reference Pickrell and Pennisi2020), with changing climatic conditions and potentially reduced forest biomass in the future (Brando et al., Reference Brando, Soares-Filho, Rodrigues, Assuncao, Morton, Tuchschneider, Fernandes, Macedo, Oliveira and Coe2020).

Recent fires have likely caused significant impacts on human health. Wildfire smoke is known to impact respiratory health, and there is growing evidence of impacts on cardiovascular health (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Rappold, Vargo, Cascio, Kharrazi, McNally and Hoshiko2020), mortality (Magzamen et al., Reference Magzamen, Gan, Liu, O'Dell, Ford, Berg, Bol, Wilson, Fischer, Kenny and Pierce2021), birth outcomes (Abdo et al., Reference Abdo, Ward, Dell, Ford, Pierce, Fischer and Crooks2019; Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Tantrakarnapa, Johnston, Loh, Steinle, Vardoulakis and Cherrie2021) and mental health (Silveira et al., Reference Silveira, Kornbluh, Withers, Grennan, Ramanathan and Mishra2021). Smoke from wildfires also affects local and distant air quality (the 2019–2020 Australian wildfires affected New Zealand and South America) (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Azzi, White, Salter, Trieu, Morgan, Rahman, Watt, Riley, Chang, Barthelemy, Fuchs, Lieschke and Nguyen2021), and smoke from Siberian fires has affected North America (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Strawbridge, Knowland, Keller and Travis2021). The full health impact of the 2019–2020 wildfires will not be known for some time due to lags in the availability of health data, but current assessments estimate around 90 increased deaths in Washington State (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Austin, Xiang, Gould, Larson and Seto2021) in 2020, and over 400 additional deaths and a few thousand increased hospitalizations from the 2019–2020 bushfires in Australia (Borchers Arriagada et al., Reference Borchers Arriagada, Palmer, Bowman, Morgan, Jalaludin and Johnston2020). Because these studies rely on concentration-response functions from non-wildfire air pollution studies, we would expect the number of deaths related to wildfire smoke to rise when using a potentially steeper concentration-response function for wildfire smoke (Aguilera et al., Reference Aguilera, Corringham, Gershunov and Benmarhnia2021; Kiser et al., Reference Kiser, Metcalf, Elhanan, Schnieder, Schlauch, Joros, Petersen and Grzymski2020).

As climate changes, the occurrence of megafires may not be constrained to fire-prone ecosystems alone. Fire regimes are expected to change in the future. A change in tropical forests' moisture, for instance, may promote much larger fires (Brando et al., Reference Brando, Soares-Filho, Rodrigues, Assuncao, Morton, Tuchschneider, Fernandes, Macedo, Oliveira and Coe2020), with important consequences for the world's biodiversity, regional human health and global climate system.

3.4 Insight 4: interconnected climate tipping elements under increasing pressure

Tipping elements are parts of the climate system that, in response to global warming and fuelled by self-reinforcing effects – can undergo nonlinear transitions into a qualitatively different state, often irreversibly. Such transitions are triggered once a critical threshold in the global temperature level is crossed – the system has reached a tipping point. The transition process can unfold over centuries to millennia (when ice sheets melt or disintegrate), over decades to centuries (when ocean currents slow down or reshape) or years to decades (especially when direct human interference additionally drives a transition, like deforestation in the Amazon rainforest).

Tipping processes are afflicted with high uncertainties (in terms of likelihood or timing, or both), but also associated with large potential impacts on societies and biosphere integrity (e.g. Berenguer et al., Reference Berenguer, Lennox, Ferreira, Malhi, Aragão, Rodrigues Barreto, Del Bon Espírito-Santo, Figueiredo, França, Gardner, Joly, Palmeira, Quesada, Rossi, Moraes de Seixas, Smith, Withey and Barlow2021; Gatti et al., Reference Gatti, Basso, Miller, Gloor, Gatti Domingues, Cassol, Tejada, Aragão, Nobre, Peters, Marani, Arai, Sanches, Corrêa, Anderson, Von Randow, Correia, Crispim and Neves2021; Golledge et al., Reference Golledge, Keller, Gomez, Naughten, Bernales, Trusel and Edwards2019; IPCC, 2021, Chapter 12; Ritchie et al., Reference Ritchie, Smith, Davis, Fezzi, Halleck-Vega, Harper, Boulton, Binner, Day, Gallego-Sala, Mecking, Sitch, Lenton and Bateman2020; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Pattyn, Simon, Albrecht, Cornford, Calov, Dumas, Gillet-Chaulet, Goelzer, Golledge, Greve, Hoffman, Humbert, Kazmierczak, Kleiner, Leguy, Lipscomb, Martin, Morlighem and Zhang2020). Therefore, they can be classified as high-impact, high uncertainty risks (Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Rockström, Gaffney, Rahmstorf, Richardson, Steffen and Schellnhuber2019).

3.4.1 New evidence of change

Several climate tipping elements, a subset of which – selected for their interaction – is discussed in this brief review, show significant individual changes already today.

Recent observations from Antarctica have shown that the rate at which the Antarctic Ice Sheet (AIS) may respond to environmental changes is affected by the amount of ice sheet damage (fracturing, crevassing), which itself is linked to the rate of ice discharge (Lai et al., Reference Lai, Kingslake, Wearing, Chen, Gentine, Li, Spergel and van Wessem2020; Lhermitte et al., Reference Lhermitte, Sun, Shuman, Wouters, Pattyn, Wuite, Berthier and Nagler2020). It is therefore possible for a positive mass loss feedback to develop, leading to hysteresis behaviour of the AIS (Garbe et al., Reference Garbe, Albrecht, Levermann, Donges and Winkelmann2020). Also, bedrock rebound following AIS loss may then exacerbate long-term sea-level rise by expelling water from submarine basins (Pan et al., Reference Pan, Powell, Latychev, Mitrovica, Creveling, Gomez, Hoggard and Clark2021).

The Greenland Ice Sheet (GIS) is losing mass at accelerating rates, due to meltwater runoff and ice discharge at outlet glaciers. Surface melt will continue to increase with further atmospheric warming. While ice discharge is 14% greater now than during the 1985–1999 period, the reasons for this increase differ from region to region, making it difficult to project future developments (King et al., Reference King, Howat, Candela, Noh, Jeong, Noël, van den Broeke, Wouters and Negrete2020).

There is increasing evidence from paleoclimate proxies as well as modern sea level and salinity observations that the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) has significantly weakened in past decades and is at its weakest in at least a millennium (Caesar et al., Reference Caesar, McCarthy, Thornalley, Cahill and Rahmstorf2021; Piecuch, Reference Piecuch2020; Zhu & Liu, Reference Zhu and Liu2020). Recent statistical analyses of sea-surface temperature and salinity observations give rise to the concern that this decline may be a sign of an ongoing loss of stability of the circulation, rather than just a temporal weakening (Boers, Reference Boers2021).

Although rainfall changes have been driving plant compositional changes within the Amazon (Esquivel-Muelbert et al., Reference Esquivel-Muelbert, Baker, Dexter, Lewis, Brienen, Feldpausch, Lloyd, Monteagudo-Mendoza, Arroyo, Álvarez-Dávila, Higuchi, Marimon, Marimon-Junior, Silveira, Vilanova, Gloor, Malhi, Chave, Barlow and Phillips2019), basin-wide dieback is judged as unlikely to occur due to projected climate change alone (Chai et al., Reference Chai, Martins, Nobre, von Randow, Chen and Dolman2021). However, as forest degradation is higher than previously quantified (Matricardi et al., Reference Matricardi, Skole, Costa, Pedlowski, Samek and Miguel2020; Qin et al., Reference Qin, Xiao, Wigneron, Ciais, Brandt, Fan, Li, Crowell, Wu, Doughty, Zhang, Liu, Sitch and Moore III2021), reaching up to 17% of the Amazon basin, and additionally 18% of the area is already deforested (Bullock et al., Reference Bullock, Woodcock, Souza and Olofsson2020), interactions between direct human-induced and climate changes may lead to regime shifts in parts of the Amazon rainforests (e.g. Longo et al., Reference Longo, Saatchi, Keller, Bowman, Ferraz, Moorcroft, Morton, Bonal, Brando, Burban, Derroire, dos-Santos, Meyer, Saleska, Trumbore and Vincent2020). Events such as the 2015/2016 El Niño caused an extreme and prolonged drought, which fuelled extensive and damaging fires. This has been putting some regions of the Amazon under such pressure that plant mortality rates remained elevated for 2–3 years after the event – particularly where forests had already been modified by human activities (Berenguer et al., Reference Berenguer, Lennox, Ferreira, Malhi, Aragão, Rodrigues Barreto, Del Bon Espírito-Santo, Figueiredo, França, Gardner, Joly, Palmeira, Quesada, Rossi, Moraes de Seixas, Smith, Withey and Barlow2021). The southeastern part of the Amazon basin has turned into a net source of carbon to the atmosphere, not even taking the effect of fires into account (Gatti et al., Reference Gatti, Basso, Miller, Gloor, Gatti Domingues, Cassol, Tejada, Aragão, Nobre, Peters, Marani, Arai, Sanches, Corrêa, Anderson, Von Randow, Correia, Crispim and Neves2021).

3.4.2 New evidence of interaction

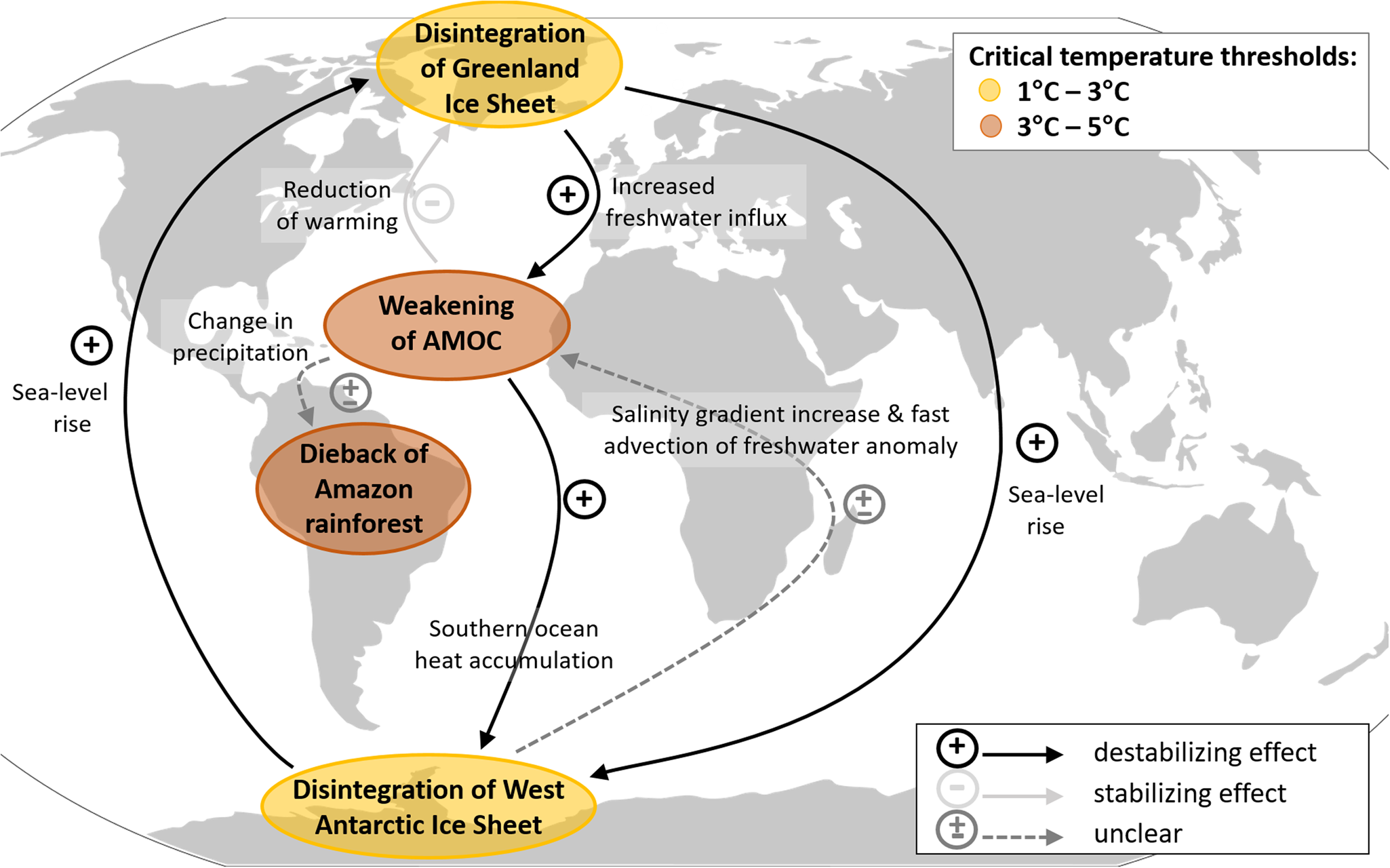

These are examples of tipping elements subject to different types of interactions (Gaucherel & Moron, Reference Gaucherel and Moron2017): For instance, new research has re-emphasized the importance of ice-sheet–climate interactions, showing that at times in the past, meltwater from the GIS raised global mean sea level, directly influencing AIS retreat (Gomez et al., Reference Gomez, Weber, Clark, Mitrovica and Han2020). Increased freshwater flux into the North Atlantic from Greenland meltwater can lead to a weakening of the AMOC (Rahmstorf et al., Reference Rahmstorf, Box, Feulner, Mann, Robinson, Rutherford and Schaaernicht2015). Large-scale inter-hemispheric heat redistribution caused by AMOC slowdown could alter precipitation patterns over the Amazon (Ciemer et al., Reference Ciemer, Winkelmann, Kurths and Boers2021), with regional differences – rainfall can be enhanced or reduced. Therefore, stabilizing and destabilizing effects are both possible, and the overall effect remains uncertain.

3.4.3 The risk of cascades

In addition to the risks from individual tipping processes, an overarching, additional layer of risk has emerged: Interactions among tipping elements can produce cascading non-linear transitions, that is, one tipping event actually leading to the tipping of another element (Brovkin et al., Reference Brovkin, Brook, Williams, Bathiany, Lenton, Barton, DeConto, Donges, Ganopolski, McManus, Praetorius, de Vernal, Abe-Ouchi, Cheng, Claussen, Crucifix, Gallopín, Iglesias, Kaufman and Yu2021; Lenton et al., Reference Lenton, Rockström, Gaffney, Rahmstorf, Richardson, Steffen and Schellnhuber2019; Rocha et al., Reference Rocha, Peterson, Bodin and Levin2018; Steffen et al., Reference Steffen, Rockström, Richardson, Lenton, Folke, Liverman, Summerhayes, Barnosky, Cornell, Crucifix, Donges, Fetzer, Lade, Scheffer, Winkelmann and Schellnhuber2018; Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Jones, Turney, Golledge, Fogwill, Bradshaw, Menviel, McKay, Bird, Palmer, Kershaw, Wilmshurst and Muscheler2020).

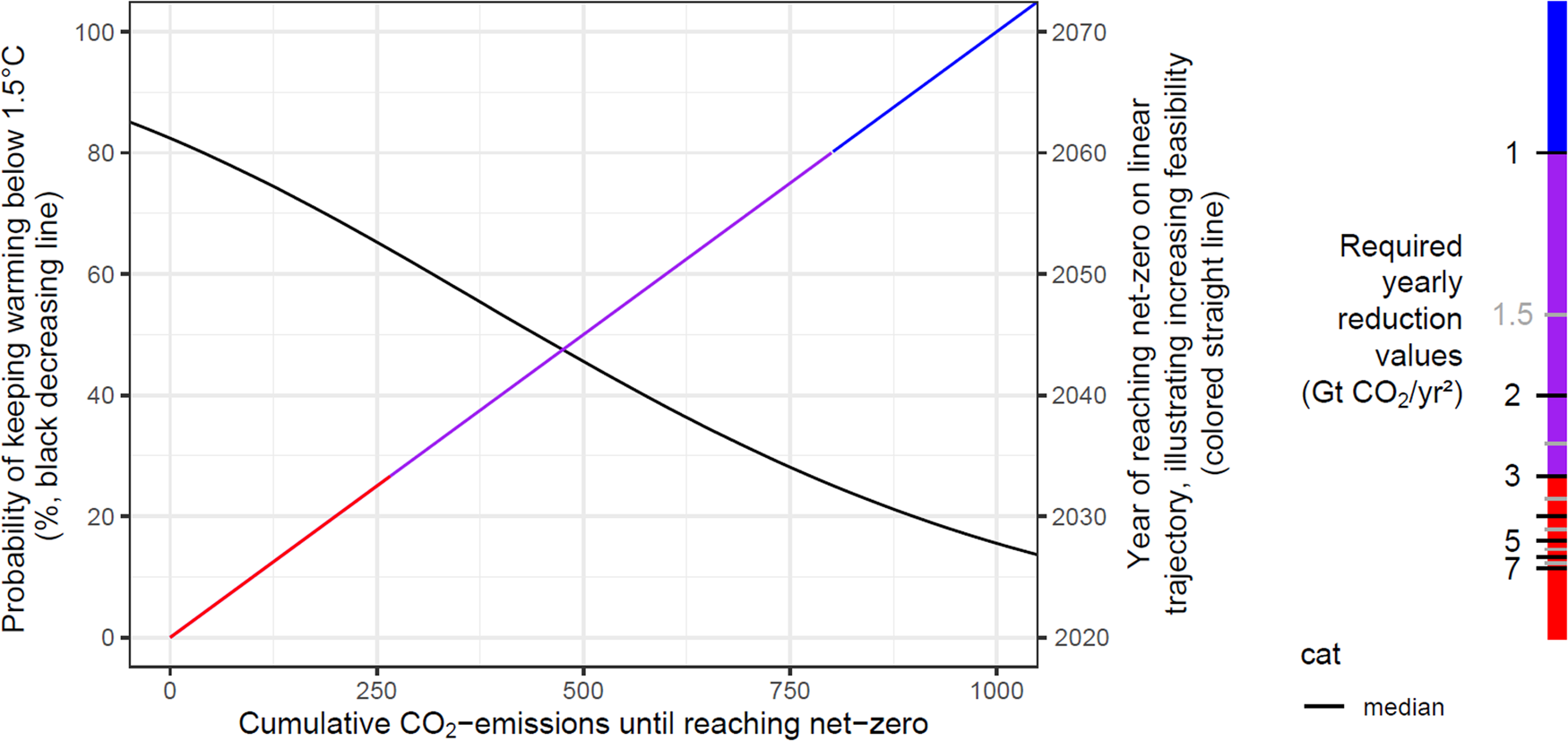

Recent modelling efforts have quantitatively addressed this risk of cascades arising from interacting tipping elements such as (Figure 4) GIS and West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS), the AMOC, and the Amazon rainforest (Dekker et al., Reference Dekker, von der Heydt and Dijkstra2018; Lohmann et al., Reference Lohmann, Castellana, Ditlevsen and Dijkstra2021; Wunderling et al., Reference Wunderling, Donges, Kurths and Winkelmann2021). Interactions between these four tipping elements could effectively lower critical temperature thresholds, hence, their overall effect on Earth's climate is destabilizing, even when taking into account the considerable uncertainties in critical threshold temperatures, interaction strengths and directions. This additional risk from emerging tipping cascades is found to increase strongly between 1 and 3 °C of global warming – adding to the risk from individual tipping elements – with potentially critical impacts on human societies, biosphere integrity and overall Earth system stability.

Figure 4. Physical interactions between four of the key climate tipping elements already under stress today by anthropogenic global warming: Greenland and West Antarctic Ice Sheets, Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation and Amazon rainforest. Arrows indicate directed stabilizing (‘+’ symbol), destabilizing (‘–’ symbol) effects and those with so far unclear direction (‘±’ symbol). Critical threshold temperatures and their uncertainty ranges of individual climate tipping elements are also indicated. Adapted from Wunderling et al. (Reference Wunderling, Donges, Kurths and Winkelmann2021).

3.5 Insight 5: global climate action must be just

Global climate action must be designed to tackle existing and anticipated inter- and intranational inequalities and injustices related to climate change. Fairer climate policies are likely to be more widely acceptable, increasing the potential for effective implementation. In this vein, climate action in the pursuit of just outcomes must respond to four dimensions of climate change inequality: impacts, responsibility, cost and capacity (Rockström et al., Reference Rockström, Gupta, Lenton, Qin, Lade, Abrams, Jacobson, Rocha, Zimm, Bai, Bala, Bringezu, Broadgate, Bunn, DeClerck, Ebi, Gong, Gordon, Kanie and Winkelmann2021; van den Berg et al., Reference van den Berg, van Soest, Hof, den Elzen, van Vuuren, Chen, Drouet, Emmerling, Fujimori, Höhne, Kõberle, McCollum, Schaeffer, Shekhar, Vishwanathan, Vrontisi, Blok, Berg, Soest and Blok2020).

Action on climate change is a matter of intra- and intergenerational justice, because climate change impacts already have affected and continue to affect vulnerable people and countries who have least contributed to the problem (Taconet et al., Reference Taconet, Méjean and Guivarch2020). Contribution to climate change is vastly skewed in terms of wealth: the richest 10% of the world population was responsible for 52% of cumulative carbon emissions based on all of the goods and services they consumed through the 1990–2015 period, while the poorest 50% accounted only for 7% (Gore, Reference Gore2020; Oswald et al., Reference Oswald, Owen, Steinberger, Yannick, Owen and Steinberger2020).

A just distribution of the global carbon budget (a conceptual tool used to guide policy) (Matthews et al., Reference Matthews, Tokarska, Nicholls, Rogelj, Canadell, Friedlingstein, Thomas, Frölicher, Forster, Gillett, Ilyina, Jackson, Jones, Koven, Knutti, MacDougall, Meinshausen, Mengis, Séférian and Zickfeld2020) would require the richest 1% to reduce their current emissions by at least a factor of 30, while per capita emissions of the poorest 50% could increase by around three times their current levels on average (UNEP, 2020). Rich countries' current and promised action does not adequately respond to the climate crisis in general, and, in particular, does not take responsibility for the disparity of emissions and impacts (Zimm & Nakicenovic, Reference Zimm and Nakicenovic2020). For instance, commitments based on Nationally Determined Contributions under the Paris Agreement are insufficient for achieving net-zero reduction targets (United Nations Environment Programme, 2020).

Much more needs to be done to minimize the unfair distribution of the costs of climate action. Climate policies that increase the cost of basic goods tend to have regressive distributional effects, hitting people on low incomes harder than richer people in relative terms (Inoue et al., Reference Inoue, Matsumoto, Morita, Arimura and Matsumoto2021; Okonkwo, Reference Okonkwo2021; Pianta & Lucchese, Reference Pianta and Lucchese2020). Resources for low-carbon technologies such as batteries and solar photovoltaic panels are often mined in poorer countries with detrimental environmental and social effects (Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Turnheim, Hook, Brock and Martiskainen2021). Recent studies show that a redistribution of resources through a global cap-and-trade system, combined with financial transfers from rich to poor countries, can avoid regressive effects (Bauer et al., Reference Bauer, Bertram, Schultes, Klein, Luderer, Kriegler, Popp and Edenhofer2020). Further, global equal per capita revenue sharing can reduce global poverty (Soergel et al., Reference Soergel, Kriegler, Leon Bodirsky, Bauer, Leimbach and Popp2021).

While unfair distribution of costs for climate change mitigation in rich countries needs to be addressed, we must generally avoid a focus on ‘compensating’ societies in high-polluting regions (Sovacool et al., Reference Sovacool, Turnheim, Hook, Brock and Martiskainen2021; Tarekegne, Reference Tarekegne2020).

Radical climate action could slow down increases in living standards in the lower- to middle-income countries (Taconet et al., Reference Taconet, Méjean and Guivarch2020) while poorer countries and people have less capacity to act on climate change. Most developing countries, as in sub-Saharan Africa, are faced with huge infrastructural deficits. These deficits, on the other hand, give them the opportunity to leapfrog to resource-efficient and climate-resilient infrastructure systems (AESA, 2021), drawing on all transitional levers for a managed exit from the high emissions development pathway. Justice requires disruption of the status quo, transforming systemic inequalities and the power relations that maintain them, towards a political economy supportive of countries with lower capacity to balance mitigation, adaptation and development priorities. International climate ambition can and must ensure co-benefits for vulnerable societies, simultaneously ensuring that (a) systems of distribution do not negatively interfere with people's access to basic goods; and (b) past, present and future rights derived from carbon budgets are protected (Lacey-Barnacle et al., Reference Lacey-Barnacle, Robison and Foulds2020; McCauley et al., Reference McCauley, Ramasar, Heffron, Sovacool, Mebratu and Mundaca2019; Newell et al., Reference Newell, Srivastava, Naess, Torres Contreras and Price2020).

3.6 Insight 6: The oft overlooked potential of demand-side solutions as vehicles of climate mitigation

Households contribute to a large share of the global carbon footprint, providing an avenue for effective action (Dubois et al., Reference Dubois, Sovacool, Aall, Nilsson, Barbier, Herrmann, Bruyère, Andersson, Skold, Nadaud, Dorner, Richardsen Moberg, Ceron, Fischer, Amelung, Baltruszewicz, Fischer, Benevise and Sauerborn2019; Hertwich & Peters, Reference Hertwich and Peters2009). Yet, the role of households is not given adequate attention in present climate change policies where the focus is largely on supply-side solutions (Creutzig et al., Reference Creutzig, Fernandez, Haberl, Khosla, Mulugetta and Seto2016). A more holistic approach that highlights both demand- and supply-side solutions is needed (Creutzig et al., Reference Creutzig, Roy, Lamb, Azevedo, Bruine De Bruin, Dalkmann, Edelenbosch, Geels, Grubler, Hepburn, Hertwich, Khosla, Mattauch, Minx, Ramakrishnan, Rao, Steinberger, Tavoni, Ürge-Vorsatz and Weber2018). This holistic approach has been described as ‘production-consumption systems’ (Mathai et al., Reference Mathai, Isenhour, Stevis, Vergragt, Bengtsson, Lorek, Mortensen, Coscieme, Scott, Waheed and Alfredsson2021). Recent research emphasized the potential of the consumption (i.e. demand) side of this system, recognizing that, through the lens of equity, there are distinct implications for different contexts.

To achieve ‘1.5 °C lifestyles’, which aim to reduce household carbon footprints to compatibility with the Paris Agreement while improving quality of life, global per capita emissions need to halve by 2030 (Ivanova & Wood, Reference Ivanova and Wood2020) with the rest being eliminated in the subsequent decade (refer to Insight 1). For high-emitting consumers in North America and Europe as well as consumer elites elsewhere, reductions will have to be far steeper both because their consumption patterns have a dramatically higher impact and to ensure a just transition that does respect development needs in lower income contexts (refer to Insight 5 for more on the just distribution of the global carbon budget). In fact, as Nielsen et al. pointed out (Nielsen et al., Reference Nielsen, Nicholas, Creutzig, Dietz and Stern2021), high socio-economic individuals with their outsized impacts should be a primary target of mitigation efforts.

The most significant areas for action include reducing individual car mobility and flying, switching to plant-based diets, and housing (e.g. location and size) (Ivanova et al., Reference Ivanova, Barrett, Wiedenhofer, Macura, Callaghan and Creutzig2020). These changes will not happen on their own and there is a growing body of work on what works to bolster behaviour changes by individuals (Khanna et al., Reference Khanna, Baiocchi, Callaghan, Creutzig, Guias, Haddaway, Hirth, Javaid, Koch, Laukemper, Löschel, del Mar Zamora and Minx2021). Additionally, given the differential carbon footprints from the micro (e.g. household) to the macro (e.g. national) scales, responsibility for demand-side measures must also be differentiated.

Achieving 1.5 °C lifestyles will require the implementation of mutually reinforcing systems by the public and business sectors to support behavioural change and modification of individuals' value systems. This would foster virtuous cycles – in which households call for supporting measures from the public and business sectors – whose measures enable households to adopt further changes that enhance the quality of life (Newell et al., Reference Newell, Daley and Twena2021). Additionally, this would provide the necessary political economy for the creation of sustainable production-consumption systems (Mathai et al., Reference Mathai, Isenhour, Stevis, Vergragt, Bengtsson, Lorek, Mortensen, Coscieme, Scott, Waheed and Alfredsson2021). These virtuous cycles are necessary if demand-side strategies are going to result in the needed drastic emissions reductions. Further, it is expected that these processes would be a trigger of tipping dynamics that are key to materializing fast-spreading processes of social and technological change towards a decarbonized society (Otto et al., Reference Otto, Wiedermann, Cremades, Donges, Auer and Lucht2020).

Debunking common assumptions, 1.5 °C lifestyles do not preclude a ‘good life’ (Millward-Hopkins et al., Reference Millward-Hopkins, Steinberger, Rao and Oswald2020), and even absolute energy reductions would not impede human well-being (Steinberger et al., Reference Steinberger, Lamb and Sakai2020). Fulfilling basic needs requires minimum levels of consumption while the carbon budget (Insight 1) (among other reasons) requires drawing an upper line of consumption. The spaces between necessary minimum and maximum acceptable consumption are ‘consumption corridors’ where individuals may choose their lifestyle (Defila & Di Giulio, Reference Defila and Di Giulio2020). Moving the entire global population into this space would greatly improve life for billions while requiring significant changes to wealth, high-consuming elites. Consumption corridors are intended as a guide for those whose consumption exceeds the acceptable maximum, and they need to be established through democratic processes that embrace social equity ideals (Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Sahakian, Gumbert, Di Giulio, Maniates, Lorek and Graf2021), so that those suffering most from climate change do not additionally carry the main burden of demand-side (price) policies.

The shift in consumer behaviour in response to COVID-19 pandemic containment measures points to the possibility of facilitating 1.5 °C lifestyles. The lockdowns increased interest in local market solutions (Sharma et al., Reference Sharma, Gupta and Jha2020) and social solidarity appeared to be a useful tool in many impoverished communities facing supply shocks (Mishra & Rath, Reference Mishra and Rath2020). Yet these changes resulted in a drop in emissions that would have to be repeated every year for two decades (Insight 1) while there is no evidence that the changes wrought by the pandemic will be permanent.

Fostering demand-side solutions would greatly facilitate meeting the Paris goals. They require behavioural change as well as actions by the public and business sectors to trigger tipping dynamics for deep systemic structural transformations. Democratic processes are needed to establish equitable minimum and maximum levels of consumption ensuring that basic needs are fulfilled for all.

3.7 Insight 7: political challenges impede the effectiveness of carbon pricing

Carbon pricing policies now cover roughly 22% of global emissions (The World Bank, 2021), yet carbon emissions continue to rise. While the economic logic of carbon pricing has been widely advocated, prices have so far been too low to have a significant effect on CO2 emissions (Green, Reference Green2021; Rafaty et al., Reference Rafaty, Dolphin and Pretis2020; The World Bank, 2021). This raises questions about political acceptability and the political economy of carbon pricing.

Though economically rational, carbon pricing faces political obstacles that may limit its effectiveness (Rosenbloom et al., Reference Rosenbloom, Markard, Geels and Fuenfschilling2020). First, carbon pricing creates upfront costs to individuals and economic agents, while promising distant climate benefits. This approach can create a political backlash (Rabe, Reference Rabe2018). Second, carbon pricing, and particularly taxes, are often regressive, though there is variation across policies (Ohlendorf et al., Reference Ohlendorf, Jakob, Minx, Schröder and Steckel2021). Without careful design (see, e.g. Cronin et al., Reference Cronin, Fullerton and Sexton2019), regressive pricing can produce further backlash or opposition from lower-income groups. The redistribution of revenues can make carbon pricing more politically acceptable to the public at large (Jagers et al., Reference Jagers, Lachapelle, Martinsson and Matti2021). However, progressive policies can also spur backlash from average- or upper-income groups, who are required to pay more in accordance with their consumption (Wetts, Reference Wetts2020).

Some have recommended a universal carbon price through linked carbon markets or a global carbon price floor (Carattini et al., Reference Carattini, Kallbekken and Orlov2019; Keohane et al., Reference Keohane, Petsonk and Hanafi2017; Mehling et al., Reference Mehling, Metcalf and Stavins2018). Yet, the difficulties in finalizing the rules for Article 6 of the Paris Agreement are evidence of the political challenges of this approach. Sectoral carbon prices and border tax adjustments could help overcome some resistance. However, the EU-proposed border tax adjustment policy will raise new political and economic challenges for trade (Evans et al., Reference Evans, Mehling, Ritz and Sammon2020), particularly for some low- and middle-income countries, which are increasingly home to emissions-intensive production. Moreover, there are important equity implications of border-tax adjustments (Aylor et al., Reference Aylor, Gilbert, Lang, McAdoo, Öberg, Pieper, Sudmeijer and Voigt2020).

These political obstacles have impeded the efficacy of carbon pricing. For instance, the received wisdom has been that carbon prices should start low and rise over time, but because of political and economic dynamics, the price levels have generally remained low. Sharp short-term increases are needed to significantly contribute to the Paris targets (Strefler et al., Reference Strefler, Kriegler, Bauer, Luderer, Pietzcker, Giannousakis and Edenhofer2021), but these would likely incur political resistance. Time remains a problem: Krausmann et al. (Reference Krausmann, Wiedenhofer and Haberl2020) show that the majority of emissions come from maintenance and use of infrastructures, leading to low price elasticity. Regulatory capacity also contributes to effective implementation (Levi et al., Reference Levi, Flachsland and Jakob2020). Moreover, carbon pricing may drive efficiency improvements and fuel switching but have a limited effect on decarbonization (Green, Reference Green2021). The extensive and persistent subsidies for fossil fuels create a countervailing negative price that undermines price signals created by carbon pricing (Coady et al., Reference Coady, Parry, Le and Shang2019). And finally, the use of carbon offsets in emissions trading systems may diminish reductions due to problems with additionality (Cullenward & Victor, Reference Cullenward and Victor2020; Haya et al., Reference Haya, Cullenward, Strong, Grubert, Heilmayr, Sivas and Wara2020).

To address the political obstacles that have beset carbon pricing, we recommend the following measures:

(1) Rather than seeking a global carbon price, sectoral-based carbon pricing can offer a first step towards expanding the scope of carbon pricing, by addressing potential competition, and therefore political challenges. The diversity of economic and political circumstances should be acknowledged (Verbruggen & Brauers, Reference Verbruggen and Brauers2020).

(2) Tax revenues should be used in a transparent and fair manner (including to lower other taxes, fund public goods and climate investment), or be refunded, to avoid regressive effects and to increase acceptance (Hagem et al., Reference Hagem, Hoel and Sterner2020).

(3) To drive transformative decarbonization, carbon pricing should be complemented by other approaches in ‘bundles’ of climate policy instruments and sequenced appropriately (Pahle et al., Reference Pahle, Burtraw, Flachsland, Kelsey, Biber, Meckling, Edenhofer and Zysman2018). Policy should include large domestic investments in renewable energy production and infrastructure and adaptation measures as well as non-market-based policies such as standards and regulations (Bergquist et al., Reference Bergquist, Mildenberger and Stokes2020; Cullenward & Victor, Reference Cullenward and Victor2020). These should target both demand for and supply of fossil fuels (Green & Denniss, Reference Green and Denniss2018).

(4) Carbon prices should be applied to a larger share of global emissions and be sufficiently high to drive substantial decarbonization.

(5) The use of offsets should be carefully controlled (Cullenward & Victor, Reference Cullenward and Victor2020; Green, Reference Green2017), and fossil fuel subsidies reduced as quickly as possible (IEA, 2021).

3.8 Insight 8: nature-based solutions can form a meaningful part of the pathway to Paris but look at the fine-print

Nature-based solutions (NbS) involve working with nature to address societal challenges such as climate change, biodiversity loss and social equity. They are actions that protect, restore and better manage natural or modified ecosystems (Seddon et al., Reference Seddon, Chausson, Berry, Girardin, Smith and Turner2020). NbS involve a wide range of ecosystems, both aquatic and on land. A prominent, but by far not the only example are forests, where measures include reducing deforestation, forest restoration and managing farm and timber lands better. Among carbon-rich natural ecosystems with high rates of conversion are peatlands and mangroves. Recent scientific debate around NbS focused on their role in climate change mitigation and adaptation, equitable implementation, and financing and governance needs.

3.8.1 Nbs can contribute to climate mitigation and adaptation

Reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 requires rapid reductions of fossil fuel emissions complemented by some carbon dioxide removal (CDR) for very hard-to-abate emissions (Fuss et al., Reference Fuss, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Jones, Lyngfelt, Peters and Van Vuuren2020). Compared with other CDR options, NbS are cost-effective, technology-ready and can offer a multitude of local benefits when appropriately implemented. These include climate change adaptation and risk mitigation, for example, flood control, biodiversity preservation, socio-economic development and co-benefits to human health and well-being (see Insight 10 for more on co-benefits from NbS) (Chausson et al., Reference Chausson, Turner, Seddon, Chabaneix, Girardin, Kapos, Key, Roe, Smith, Woroniecki and Seddon2020; Seddon et al., Reference Seddon, Smith, Smith, Key, Chausson, Girardin, House, Srivastava and Turner2021). Massive new monoculture plantations do not fall under the conditions set for NbS.

NbS can provide mitigation benefits in the short term, and can play a limited but important role in the transition to net-zero in the coming decades (Fuss et al., Reference Fuss, Canadell, Ciais, Jackson, Jones, Lyngfelt, Peters and Van Vuuren2020; Girardin et al., Reference Girardin, Jenkins, Seddon, Allen, Lewis, Wheeler, Griscom and Malhi2021) – more about the potential scale is expected to be assessed in the upcoming IPCC AR6 report from Working Group III. However, feedbacks in the Earth System and climatic risks to ecosystem stability make the potential of NbS for mitigation beyond 2050 uncertain (Anderegg et al., Reference Anderegg, Trugman, Badgley, Anderson, Bartuska, Ciais, Cullenward, Field, Freeman, Goetz, Hicke, Huntzinger, Jackson, Nickerson, Pacala and Randerson2020; Koch et al., Reference Koch, Brierley and Lewis2021). Hence, NbS for climate change mitigation need to supplement, and cannot replace, decarbonization efforts, which remain key to limit global warming to 1.5 °C (IPCC, 2019a).

Importantly, scenarios that limit warming to 1.5 °C simultaneously assume: (1) net zero CO2 emissions by 2050 and net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the 2060s; (2) shifts away from GHG-intensive food systems; (3) CDR; and (4) maintained resilience in natural ecosystems (IPCC, 2018). However, implementing NbS requires using the right approaches and metrics (for climate, biodiversity and livelihoods) in order to reap the full benefits of a range of Sustainable Development Goals (Seddon et al., Reference Seddon, Chausson, Berry, Girardin, Smith and Turner2020).

3.8.2 Equity and procedural justice are central to implementing NbS

Much of the carbon-saving potential of NbS is located in the Global South (Strassburg et al., Reference Strassburg, Iribarrem, Beyer, Cordeiro, Crouzeilles, Jakovac, Junqueira, Lacerda, Latawiec, Balmford, Brooks, Butchart, Chazdon, Erb, Brancalion, Buchanan, Cooper, Díaz, Donald, F and Visconti2020). Regulation and institutional support are critical to overcome barriers and ensure equitable outcomes and procedural justice. Using NbS without a just distribution of the remaining carbon budget unfairly shifts the North's emission reduction burden onto the South (Fleischman et al., Reference Fleischman, Basant, Chhatre, Coleman, Fischer, Gupta, Güneralp, Kashwan, Khatri, Muscarella, Powers, Ramprasad, Rana, Rodriguez Solorzano and Veldman2020). Areas with the biggest NbS potential in the South are largely occupied by indigenous and marginalized communities, whose rights remain predominantly unrecognized (RRI and McGill University, 2021). Recognizing local rights and knowledge (specifically respecting the condition that communities must give Free Prior Informed Consent to any changes in land use, including over changes to customary lands), ensuring decentralized governance, generating local benefits (Erbaugh et al., Reference Erbaugh, Pradhan, Adams, Oldekop, Agrawal, Brockington, Pritchard and Chhatre2020) and using a range of financial instruments that ensure the additionality of NbS to decarbonization measures can ensure fair and sustainable outcomes.

3.8.3 Nbs need integrated financing and governance structures

NbS have a significant contribution to make to global emissions reductions, yet have been receiving only a small fraction of climate mitigation financing (Dasgupta, Reference Dasgupta2021).

Finance structures for net-zero aligned, sustainable and just NbS require: (1) performance metrics measuring multiple benefits (e.g. for genuine GHG reductions, biodiversity and local livelihoods); (2) science-informed and transparent monitoring, reporting and verification (MRV), enabling the matching of large-scale carbon finance from governments, businesses and philanthropists to sustainable NbS; and (3) improvements in governance to ensure the efficient and just allocation of finance and administration (Hourcade et al., Reference Hourcade, Glemarec, de Coninck, Bayat-Renoux, Ramakrishna and Revi2021).

Many experiences have been gained on the governance and MRV challenges of managing NbS. Reduced Emissions from avoided Deforestation and land Degradation (REDD+), for example, is a results-based payment scheme for the conservation and restoration of forest carbon, providing lessons learned for managing NbS. REDD+ has not yet delivered at scale on its promise for quick and low-cost emissions reductions, partially due to the slow rate of political, economic and regulatory transformations needed to ensure compliance (Rajão et al., Reference Rajão, Soares-Filho, Nunes, Börner, Machado, Assis, Oliveira, Pinto, Ribeiro, Rausch, Gibbs and Figueira2020).

3.8.4 Possible guidelines for just and sustainable NbS

The above insights are reflected in a growing consensus on four high-level guidelines that ensure NbS interventions will be ecologically sound, net-zero aligned and socially just. NbS should: (1) not be seen as an alternative to decarbonization; (2) involve a wide range of ecosystems (see also Insight 9); (3) be designed with local communities while respecting indigenous and other rights; and (4) meaningfully support biodiversity (Pörtner et al., Reference Pörtner, Scholes, Agard, Archer, Arneth, Bai, Barnes, Burrows, Chan, Cheung, Diamond, Donatti, Duarte, Eisenhauer, Foden, Gasalla, Handa, Hickler, Hoegh-Guldberg and Ngo2021; Seddon et al., Reference Seddon, Smith, Smith, Key, Chausson, Girardin, House, Srivastava and Turner2021).

3.9 Insight 9: building resilience of marine ecosystems is achievable by climate-adapted conservation and management, and global stewardship

Marine biodiversity is the key foundation for the structure and functioning of ocean ecosystems that provide essential services and benefits supporting human well-being on local to global scales. Yet, marine ecosystems are exposed to manifold impacts of climate change and other anthropogenic pressures that are accelerating in magnitude and extent (Jouffray et al., Reference Jouffray, Blasiak, Norstrom, Osterblom and Nystrom2020). This includes ocean warming, acidification, deoxygenation and extreme events, as well as exploitation, mining, pollution (eutrophication, toxins, organic waste, plastics, litter), habitat destruction, unsustainable fishing and aquaculture, invasive species and shipping (Bates & Johnson, Reference Bates and Johnson2020; Boyce et al., Reference Boyce, Lotze, Tittensor, Carozza and Worm2020; Glibert, Reference Glibert2020; Heinze et al., Reference Heinze, Blenckner, Martins, Rusiecka, Döscher, Gehlen, Gruber, Holland, Hov, Joos, Matthews, Rodven and Wilson2021). Today, more than 1300 marine species are threatened with extinction (Figure 5a), 34.2% of fish stocks are overexploited, most ocean areas experience the mentioned anthropogenic impacts cumulatively, and 33–50% of vulnerable habitats have been lost (Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Agusti, Barbier, Britten, Castilla, Gattuso, Fulweiler, Hughes, Knowlton, Lovelock, Lotze, Predragovic, Poloczanska, Roberts and Worm2020).

Figure 5. Major current threats and climate-adapted solutions to marine biodiversity conservation. (a) Percentage of all vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered marine species that are threatened by different anthropogenic impacts including climate change (redrawn from Luypaert et al., Reference Luypaert, Hagan, McCarthy and Poti2020, with updated IUCN data from May 2021). (b) Percentage of common climate-change adaptation strategies employed in the design of existing or future marine protected areas (MPAs) either as a single measure (dark shade) or in conjunction with other strategies (light shade) out of n = 27 case studies (redrawn from Wilson et al., Reference Wilson, Tittensor, Worm and Lotze2020).

New evidence suggests that substantial restoration across many components of marine ecosystems by 2050 is challenging but achievable, although climate change poses new threats that require rethinking of conservation, management and governance efforts (Duarte et al., Reference Duarte, Agusti, Barbier, Britten, Castilla, Gattuso, Fulweiler, Hughes, Knowlton, Lovelock, Lotze, Predragovic, Poloczanska, Roberts and Worm2020; O'Hara et al., Reference O'Hara, Frazier and Halpern2021). For example, due to warming and an excessive nutrient input, the oceanic oxygen content has demonstrably declined since around 1960, leading to an expansion of deep sea oxygen minimum zones and more frequent hypoxia in coastal systems (Oschlies, Reference Oschlies2021). Deoxygenation accelerates the emission of greenhouse gases such as nitrous oxide and methane, reduces habitat quantity and quality for many species, elevates vulnerability to fishing, for example, for the ocean's widest ranging sharks (Vedor et al., Reference Vedor, Queiroz, Mucientes, Couto, da Costa, Dos Santos, Vandeperre, Fontes, Afonso, Rosa, Humphries and Sims2021) and threatens ocean ecosystem services at large. Warming waters shift species distributions and reduce biomass across trophic levels, and heat waves threaten, for example, the survival of coral reefs and possibly temperate kelp forests. Healthy ocean ecosystems are more resilient to climate change and can help to mitigate climate change effects by acting as blue carbon sinks via marine sediments, algae, vegetated habitats and large animals (Atwood et al., Reference Atwood, Witt, Mayorga, Hammill and Sala2020; Filbee-Dexter & Wernberg, Reference Filbee-Dexter and Wernberg2020). The sustainable management of fish stocks (which account for 17% of global meat consumption) could sustain and even increase their current contribution to meet the increasing global food demand (Costello et al., Reference Costello, Cao, Gelcich, Cisneros-Mata, Free, Froehlich, Golden, Ishimura, Maier, Macadam-Somer, Mangin, Melnychuk, Miyahara, Moor, Naylor, Nostbakken, Oea, O'Reilly, Parma and Lubchenco2020).

Effective biodiversity protection and ecosystem recovery require coordinated inclusive and adaptive governance across all levels that sets clear targets and strong actions in a global stewardship context. Successful recovery and restoration actions have included exploitation bans and restrictions, endangered species legislation, habitat protection and restoration, and invasive species and pollution controls. Yet stressors often interact with each other, requiring cumulative-impact assessment and climate-adapted and ecosystem-based management (Franke et al., Reference Franke, Blenckner, Duarte, Ott, Fleming, Antia, Reusch, Bertram, Hein, Kronfeld-Goharani, Dierking, Kuhn, Sato, van Doorn, Wall, Schartau, Karez, Crowder, Keller and Prigge2020; Tittensor et al., Reference Tittensor, Beger, Boerder, Boyce, Cavanagh, Cosandey-Godin, Crespo, Dunn, Ghiffary, Grant, Hannah, Halpin, Harfoot, Heaslip, Jeffery, Kingston, Lotze, McGowan, McLeod and Worm2019). The current fragmented ocean governance system is often insufficient for managing this complexity and the cross-sectoral challenges.

Climate-smart conservation can build resilience into the global marine protected area (MPA) network (Sala et al., Reference Sala, Mayorga, Bradley, Cabral, Atwood, Auber, Cheung, Costello, Ferretti, Friedlander, Gaines, Garilao, Goodell, Halpern, Hinson, Kaschner, Kesner-Reyes, Leprieur, McGowan and Lubchenco2021) by including climate refugia with little projected change, high species turnover areas with rapid evolution potential, hotspots of threatened biodiversity, but also proper representation of diverse habitats and biomes, and corridors ensuring connectivity (Figure 5b). Protecting blue carbon areas is an important NbS to climate change mitigation with co-benefits for biodiversity protection. Carbon sequestration and storage in mangroves, seagrass beds and saltmarshes can be highly effective, but kelp forests are often overlooked. With their global distribution and large standing biomass, they store substantial carbon (e.g. 30% of blue carbon in Australia (Filbee-Dexter & Wernberg, Reference Filbee-Dexter and Wernberg2020)) but are threatened by ocean warming. Marine sediments are also globally important carbon sinks, which are disturbed by expanding seafloor trawling and seabed mining. The lack of protection (only approximately 2% of sediment carbon stocks are in fully protected areas) makes marine carbon stocks highly vulnerable to human disturbances, amounting to an estimated 1.47 Pg of aqueous CO2 emissions (equivalent to 15–20% of atmospheric CO2 absorbed by the ocean each year) (Atwood et al., Reference Atwood, Witt, Mayorga, Hammill and Sala2020).

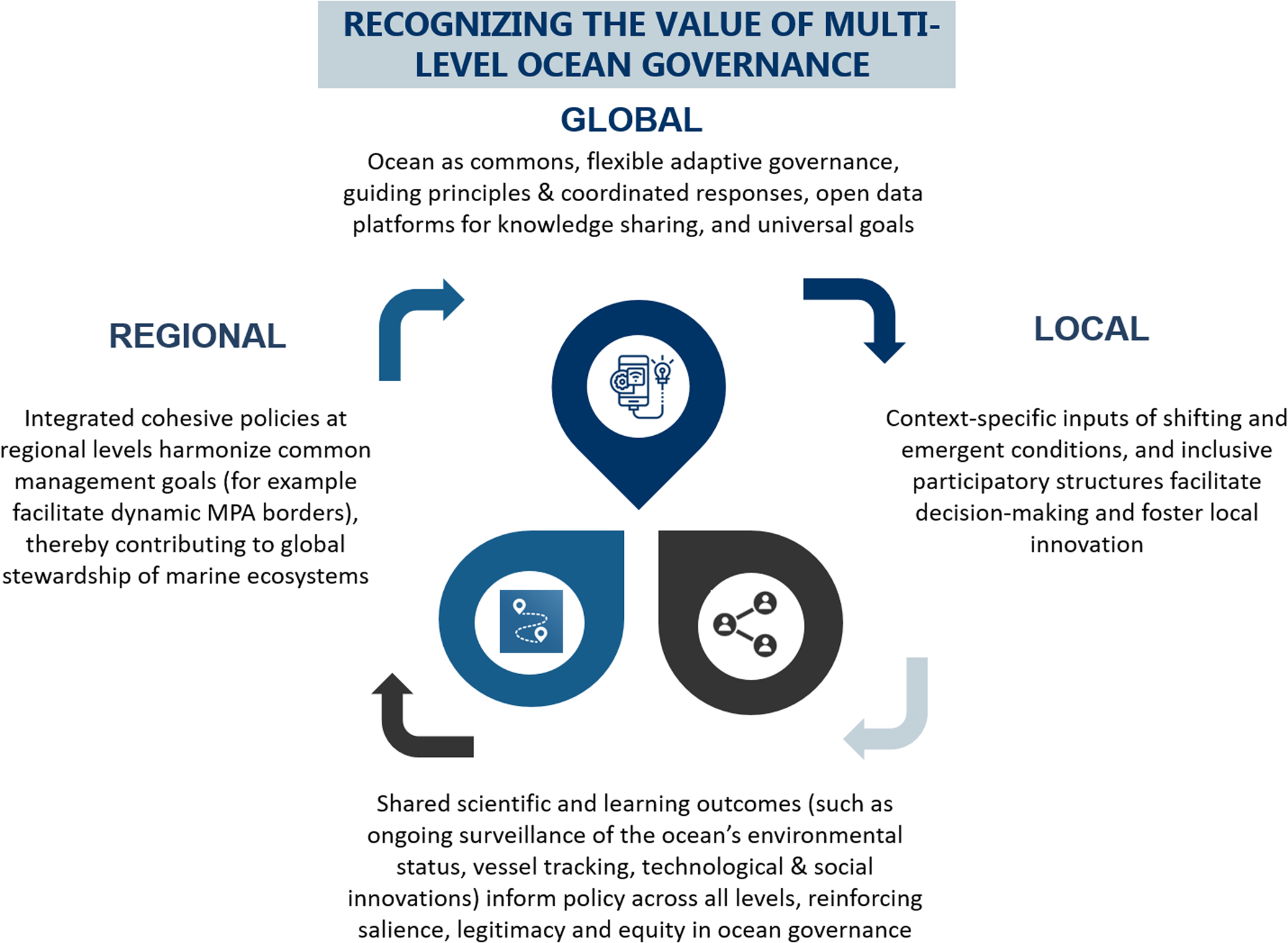

To overcome these limitations, a new ocean governance system should be coherent, reflexive and responsive to rapidly shifting ocean dynamics in time and space to facilitate decision-making in deep uncertainty (Figure 6) (Brodie Rudolph et al., Reference Brodie Rudolph, Ruckelshaus, Swilling, Allison, Osterblom, Gelcich and Mbatha2020; Haas et al., Reference Haas, Mackay, Novaglio, Fullbrook, Murunga, Sbrocchi, McDonald, McCormack, Alexander, Fudge, Goldsworthy, Boschetti, Dutton, Dutra, McGee, Rousseau, Spain, Stephenson, Vince and Haward2021). Governance efforts should be shaped by context-specific evidence-based solutions and need to consider underlying socio-ecological pathways and connect ocean health to human health. Currently, national and international efforts, bolstered by the United Nations (UN) Decade of Ocean Science, aim to expand the global network of MPAs from 7.7 to 30% and to reach Aichi biodiversity targets and UN Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. Overall, the push towards a blue economy brings many challenges as well as opportunities. With effective, globally and regionally coordinated protection, the ocean offers triple benefits: preserving unique biodiversity, seafood provision and carbon storage. Efforts must be informed by marine spatial planning, climate and ecosystem-based management, and multi-functional conservation to deal with accelerating pressures, and balance resource use with the protection of biodiversity and ocean health.

Figure 6. Increasing recognition of the need for multi-level governance of marine ecosystems to allow for adaptive responses to systemic changes in the ocean. Emergent adaptive responses occur as a result of commons-oriented global ocean stewardship that is guided by science, supported by regional collaboration and informed by local conditions and innovations.

3.10 Insight 10: costs of climate change mitigation can be justified by the benefits to the health of humans and nature

Estimates of the health co-benefits of mitigation policies indicate that the economic value of avoiding and postponing hospitalizations and premature deaths, while excluding climate change benefits, is larger than the costs of climate mitigation (Hess et al., Reference Hess, Ranadive, Boyer, Aleksandrowicz, Anenberg, Aunan, Belesova, Bell, Bickersteth, Bowen, Burden, Campbell-Lendrum, Carlton, Cissé, Cohen, Dai, Dangour, Dasgupta, Frumkin and Ebi2020). Not investing in mitigation efforts means continued detrimental health effects that could be prevented before climate benefits are apparent (Chang et al., Reference Chang, Hess, Balbus, Buonocore, Cleveland, Grabow, Neff, Saari, Tessum, Wilkinson, Woodward and Ebi2017). Furthermore, there is a need to accelerate these investments to prevent exacerbating injustice because the impacts of climate change on the health of both humans and nature are disproportionately felt by communities that are socially, politically, geographically and/or economically marginalized (Pörtner et al., Reference Pörtner, Scholes, Agard, Archer, Arneth, Bai, Barnes, Burrows, Chan, Cheung, Diamond, Donatti, Duarte, Eisenhauer, Foden, Gasalla, Handa, Hickler, Hoegh-Guldberg and Ngo2021).

3.10.1 Mitigation options in key sectors

The three main changes to the transport sector that would benefit mitigation and both the health of human and nature are: (1) switching to electric vehicles powered by clean energy, thereby reducing air pollution; (2) reducing travel distances through urban planning and remote work, thereby reducing traffic injuries, noise and air pollution; and (3) switching to walking, cycling and public transport, with physical activity benefits (Brand, Reference Brand2021; Glazener et al., Reference Glazener, Sanchez, Ramani, Zietsman, Nieuwenhuijsen, Mindell, Fox and Khreis2021). Tools are now available to estimate carbon and health economic co-benefits of active travel using a measure called the Value of Statistical Life (Götschi et al., Reference Götschi, Kahlmeier, Castro, Brand, Cavill, Kelly and Racioppi2020).

Critical for agriculture, forestry and food sectors, nature provides significant benefits for human health by supporting climate change mitigation and increasing resilience (Johnson & Gerber, Reference Johnson and Gerber2021); however, only in limited cases have these been valued in economic terms (Fisher et al., Reference Fisher, de Wit and Ricketts2021; Lawler et al., Reference Lawler, Rinnan, Michalak, Withey, Randels and Possingham2020). Biodiversity losses due to climate change lead to reductions in services provided by nature to society (reduced crop yields and nutrition, fish catches, losses from flooding and erosion, and loss of potential new sources of medicine (Applequist et al., Reference Applequist, Brinckmann, Cunningham, Hart, Heinrich, Katerere and Van Andel2020; Ebi et al., Reference Ebi, Anderson, Hess, Kim, Loladze, Neumann, Singh, Ziska and Wood2021; OECD, 2021)), with implied significant welfare costs running into billions of USD.

The energy sector also plays an important role. Across different scenarios, depending on the scale and context, bioenergy, carbon capture and storage and nuclear power have quantified health co-benefits that exceed mitigation costs (Sampedro et al., Reference Sampedro, Smith, Arto, González-Eguino, Markandya, Mulvaney, Pizarro-Irizar and Van Dingenen2020). Health co-benefits also outweigh mitigation costs in county-level studies conducted in the US (Perera et al., Reference Perera, Cooley, Berberian, Mills and Kinney2020; Sergi et al., Reference Sergi, Adams, Muller, Robinson, Davis, Marshall and Azevedo2020) and South Korea (Kim et al., Reference Kim, Xie, Dai, Fujimori, Hijioka, Honda, Hashizume, Masui, Hasegawa, Xu, Yi and Kim2020) up to 2050.

Mitigation techniques in the industry sector, including changes in material flows, improved efficiency, and changes in production methods and technologies, are associated with health economic co-benefits (IPCC, 2014, Chapter 10).

Changing people's lifestyles can provide health co-benefits to nature. For example, reducing meat and dairy intake can reduce the environmental impact of food production (Jarmul et al., Reference Jarmul, Dangour, Green, Liew, Haines and Scheelbeek2020; Volta et al., Reference Volta, Turrini, Carnevale, Valeri, Gatta, Polidori and Maione2021). The ‘syndemic’ of obesity, undernutrition and climate change (Swinburn et al., Reference Swinburn, Kraak, Allender, Atkins, Baker, Bogard, Brinsden, Calvillo, De Schutter, Devarajan, Ezzati, Friel, Goenka, Hammond, Hastings, Hawkes, Herrero, Hovmand, Howden and Dietz2019) acknowledges common drivers and solutions, and the overconsumption and inequitable distribution of resources that have contributed to these overlapping health threats.

3.10.2 The way forward

Accounting for co-benefits from the health of nature (Taillardat et al., Reference Taillardat, Thompson, Garneau, Trottier and Friess2020) and humans is needed (OECD, 2021) and increases the incentive for climate mitigation. NbS, as discussed in Insight 8, can provide such co-benefits with biodiversity conservation (Griscom et al., Reference Griscom, Busch, Cook-Patton, Ellis, Funk, Leavitt, Lomax, Turner, Chapman, Engelmann, Gurwick, Landis, Lawrence, Malhi, Schindler Murray, Navarrete, Roe, Scull, Smith and Worthington2020; Lenton, Reference Lenton2020) or restoration efforts, although restoration is costlier than conservation (Dasgupta, Reference Dasgupta2021). As an example, a recent scenario analysis showed that prevention costs for 10 years can be as low as 2% of the cost of the pandemic posits (Dobson et al., Reference Dobson, Pimm, Hannah, Kaufman, Ahumada, Ando, Bernstein, Busch, Daszak, Engelmann, Kinnaird, Li, Loch-Temzelides, Lovejoy, Nowak, Roehrdanz and Vale2020). Even though research on the origins of the pandemic is still in its infancy, the economics are encouraging.

Well-designed mitigation interventions can thus promote healthy nature, lower public health risks, and save costs globally while minimizing trade-offs. Notwithstanding that careful consideration is needed for policies to incorporate issues of justice and the distribution of benefits. In addition, raising awareness on the economics for co-benefits to the health of humans and nature can serve as motivation in all sectors to increase climate change mitigation investments in low-, middle- and high-income countries.

4. Discussion and perspectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a powerful example of how the combination of short-term shocks and long-term stressors can have extreme impacts. COVID-19 has revealed elements of governance, markets, inequities and the environment that illustrate how the climate crisis could impact the planet and the global society. As with the impacts of climate change, injustices within communities and across the world have become inescapably apparent, with dramatically greater burdens and mortality rates among non-white people and women, and lower-income groups and countries more generally.

Due to climate change, ecosystems and people are confronted with unprecedented, often locally new, climate-forced impacts, with humanitarian crises looming as a result of degrading living conditions and the potential for cascading risks across various scales.

The path to achieving the Paris Agreement's 1.5 °C target is very narrow – just and targeted measures are needed urgently at all levels: structural, political and individual