1. Introduction

Gambling disorder (GD) constitutes a psychiatric condition categorized in the latest version of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Health Disorders (DSM-5) [Reference American Psychiatric Association1] as a non-substance-related addiction. This disorder is characterized by a recurrent and persistent pattern of gambling behavior that leads to clinically significant distress. Patients with GD often suffer from cognitive distortions, such as illusions of control [Reference Gaissmaier, Wilke, Scheibehenne, McCanney and Barrett2, Reference Del Prete, Steward, Navas, Fernández-Aranda, Jiménez-Murcia and Oei3], high psychopathology levels [Reference Sanacora, Whiting, Pilver, Hoff and Potenza4–Reference Barrault, Bonnaire and Herrmann6], and dysfunctional personality traits (such as high novelty seeking) [Reference del Pino-Gutiérrez, Jiménez-Murcia, Fernández-Aranda, Agüera, Granero and Hakansson7–Reference Mallorquí-Bagué, Fernández-Aranda, Lozano-Madrid, Granero, Mestre-Bach and Baño9].

In addition to this clinical symptomatology, numerous studies have highlighted the associations between GD and impulsivity [Reference Mestre-Bach, Steward, Granero, Fernández-Aranda, Talón-Navarro and Cuquerella10–Reference Steward, Mestre-Bach, Fernández-Aranda, Granero, Perales and Navas13]. Specifically, there is evidence to support that trait impulsivity affects both the aetiology and maintenance of this behavioral addiction [Reference Nower, Derevensky and Gupta14, Reference Lutri, Soldini, Ronzitti, Smith, Clerici and Blaszczynski15]. The most used framework in recent years for the study of GD has been the UPPS-P [Reference Torres, Catena, Megías, Maldonado, Cándido and Verdejo-García16, Reference Canale, Vieno, Bowden-Jones and Billieux17]. It categorizes impulsivity into five independent dimensions: sensation seeking, which refers to one’s disposition to seek exciting experiences; (lack of) perseverance, that reflects the tendency to not persist in an activity that can be arduous; (lack of) premeditation shows the tendency to act without considering the consequences of the behavior; and positive and negative urgency, understood as emotionally charged impulsive behaviors in response to positive or negative moods [Reference Berg, Latzman, Bliwise and Lilienfeld18, Reference Verdejo-García, Lozano, Moya, Alcázar and Pérez-García19].

In the case of GD, the scales that best distinguish treatment-seeking patients from healthy controls are lack of perseverance and positive and negative urgency, with GD patients endorsing greater levels in all three measures [Reference Lutri, Soldini, Ronzitti, Smith, Clerici and Blaszczynski15, Reference Michalczuk, Bowden-Jones, Verdejo-Garcia and Clark20]. It is common for patients with GD to report using gambling behavior to mitigate states of anxiety or depression, possibly due to impaired emotion regulation mechanisms [Reference Michalczuk, Bowden-Jones, Verdejo-Garcia and Clark20–Reference Navas, Contreras-Rodríguez, Verdejo-Román, Perandrés-Gómez, Albein-Urios and Verdejo-García22]. The role of sensation seeking, as assessed by the UPPS-P, is not clear in the case of GD and some studies do not support higher levels of this trait in comparison with healthy controls [Reference Michalczuk, Bowden-Jones, Verdejo-Garcia and Clark20, Reference Ledgerwood, Alessi, Phoenix and Petry23, Reference Alvarez-Moya, Jiménez-Murcia, Aymamí, Gómez-Peña, Granero and Santamaría24]. Finally, lack of premeditation has been shown to be associated with poor decision-making abilities, which is a common feature in patients with GD [Reference Torres, Catena, Megías, Maldonado, Cándido and Verdejo-García16, Reference Canale, Vieno, Bowden-Jones and Billieux17, Reference Navas, Verdejo-García, López-Gómez, Maldonado and Perales25].

According to the DSM-5, the greater presence of GD symptomatology increases the severity of the disorder [Reference American Psychiatric Association1]. In this vein, existing research recognizes the bond between impulsivity and GD severity [Reference Mallorquí-Bagué, Fagundo, Jimenez-Murcia, de la Torre, Baños and Botella26–Reference Hodgins and Holub28]. In view of this association and in order to carry out classification from a dimensional point of view, the DSM-5 proposed a new operationalization of clinical severity by numbering criteria. This system is used as an indicator of GD severity and is divided into three levels: mild (four to five criteria), moderate (six to seven), and severe (eight or nine) [Reference American Psychiatric Association1, Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain29]. However, this new classification has proven to be controversial among researchers and clinicians alike, highlighting the need to assess whether severity, as measured by these criteria, is clinically relevant [Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain29–Reference Sleczka, Braun, Piontek, Bühringer and Kraus31].

A wide range of treatment options are available for GD, including various psychological approaches (e.g. self-help groups and peer-support interventions) and pharmacological treatment [Reference Choi, Shin, Kim, Choi, Kim and Kim32]. However, not all patients with GD obtain long-term benefits from psychological interventions, with success rates at a 6-month 1-year follow-up ranging anywhere from 30% and to 71% [Reference Echeburúa, Fernández-Montalvo and Báez33–Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Álvarez-Moya, Granero, Aymamí, Gómez-Peña and Jaurrieta36]. A recent systematic review of evidence relating to pre-treatment predictors of gambling outcomes following psychological treatment identified older age, lower gambling symptom severity, lower levels of gambling behaviors and alcohol use, and higher treatment session attendance as likely predictors of successful treatment outcome [Reference Merkouris, Thomas, Browning and Dowling37]. Additionally, higher levels of sensation seeking (though not as measured by the UPPS-P) were associated with negative treatment outcomes at post-treatment or medium-term follow-up [Reference Merkouris, Thomas, Browning and Dowling37]. Findings such as these are practical for clinicians in choosing treatment strategies by allowing them to take into account the characteristics of the individual seeking treatment. Nonetheless, evidence regarding the clinical utility of current working definition of GD symptom severity boundaries is scare [Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain29, Reference Sleczka, Braun, Piontek, Bühringer and Kraus31] and recent calls have been made to incorporate broader outcome domains that extend beyond disorder-specific symptoms in order to develop a single comprehensive to measure all aspects of gambling recovery [Reference Pickering, Keen, Entwistle and Blaszczynski38].

Therefore, taking into account the findings described above, the aims of this study were threefold: 1) to explore the association between gambling-related variables and impulsivity traits in a sample of adult men who met criteria for GD; b) to estimate the predictive capacity of the impulsivity measures on GD treatment outcome (after 4 months of CBT treatment and at a two-year follow-up), namely considering relapse and dropout as outcome measures; and c) to examine the associations between DSM-5 severity categories on treatment outcome.

2. Material and methods

2.1 Participants and procedure

An initial sample of 519 patients diagnosed with GD from the Department of Psychiatry at a University Hospital, recruited between March 2013 and July 2017, was considered. They were voluntarily derived to the Gambling Disorder Unit through general practitioners or via other healthcare professionals. From this sample, 112 cases were excluded due to the fact that they decided not to enter treatment. Moreover, female patients (n = 8) and one case an incomplete evaluation were excluded. A total of 398 male patients were included in the final sample. Exclusion criteria for the study were the presence of a mental disorder (i.e. schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders) or intellectual disability. Patients were screened via a structured interview by experienced clinical psychologists and psychiatrists before being included in the study sample. These same therapists carried out the CBT therapy intervention.

The present study was carried out in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. The University Hospital Clinical Research Ethics Committee approved the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

2.2 Treatment

The cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) group treatment program used in this study consisted of 16 weekly outpatient sessions at a University Hospital, lasting 90 min each. The follow-up period of visits included evaluations at 1, 3, 6, 12 and 24 months. CBT groups were led by an experienced clinical psychologist as well as a licensed co-therapist. To ensure treatment fidelity, treatment providers were trained on how to adhere closely to the treatment manual [Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Aymamí-Sanromà, Gómez-Peña, Álvarez-Moya and Vallejo39]. The goal of this treatment plan was to educate patients on how to implement CBT strategies in order to minimize all types of gambling behavior in order to eventually obtain full abstinence. The topics addressed in the treatment plan included: psychoeducation regarding the disorder (its course, vulnerability factors, diagnostic criteria, etc.), stimulus control (money management, avoidance of potential triggers, self-exclusion programs, etc.), response prevention (alternative and compensatory behaviors), cognitive restructuring focused on illusions of control over gambling and magical thinking, emotion-regulation skills training, and other relapse prevention techniques. This treatment program has already been described elsewhere [Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Aymamí-Sanromà, Gómez-Peña, Álvarez-Moya and Vallejo39] and its short and medium-term effectiveness has been reported in other studies [Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Álvarez-Moya, Granero, Aymamí, Gómez-Peña and Jaurrieta36, Reference Jimenez-Murcia, Aymamí, Gómez-Peña, Santamaría, Álvarez-Moya and Fernández-Aranda40, Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Tremblay, Stinchfield, Granero, Fernández-Aranda and Mestre-Bach41]. Throughout treatment, attendance to treatment sessions, control of spending and the occurrence of relapses were recorded weekly on an observation sheet. A relapse was defined as the occurrence of a gambling episode once treatment had begun. This is common for many studies carried out with patients who meet criteria for GD [Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Tremblay, Stinchfield, Granero, Fernández-Aranda and Mestre-Bach41–Reference Müller, Wölfling, Dickenhorst, Beutel, Medenwaldt and Koch43]. Failure to attend three consecutive CBT sessions was considered a criterion for dropout.

2.3 Instruments

2.3.1 DSM-5 Criteria [Reference American Psychiatric Association1]

Patients were diagnosed with pathological gambling if they met DSM-IV-TR criteria for this disorder [Reference American Psychiatric Association44]. It should be noted that with the release of the DSM-5 [Reference American Psychiatric Association1], the term pathological gambling was replaced with GD. All patient diagnoses were reassessed and recodified post hoc and only patients who met DSM-5 criteria for GD were included in our analysis.

2.3.2 South oaks gambling screen (SOGS) [Reference Lesieur and Blume45]

This 20-item screening questionnaire discriminates between probable pathological, problem and non-problem gamblers based on the frequency and nature of gambling behaviors. The Spanish validation used in this work showed excellent internal consistency (α = 0.94) and test-retest reliability (r = 0.98) [Reference Echeburúa, Báez, Fernández and Páez46].

2.3.3 Impulsive behavior scale (UPPS-P) [Reference Whiteside, Lynam, Miller and Reynolds47]

The UPPS-P measures five facets of impulsivity through self-report on 59 items: negative urgency; positive urgency; lack of premeditation; lack of perseverance; and sensation seeking. Individuals are asked to consider acts/incidents during the last 6 months when rating their behaviors and attitudes. The Spanis H-L anguage adaptation showed good reliability (Cronbach’s α between 0.79 and 0.93) and external validity [Reference Verdejo-García, Lozano, Moya, Alcázar and Pérez-García19]. Consistency in the study sample was between good (α = 0.75 for lack of perseverance scale) to excellent (α = 0.92 for positive urgency).

2.3.4 Other sociodemographic and clinical variables

Additional sociodemographic and variables related to gambling were measured using a semi-structured, face-to-face clinical interview described elsewhere [Reference Jiménez-Murcia, Aymamí-Sanromà, Gómez-Peña, Álvarez-Moya and Vallejo39].

2.4 Statistics

Statistical analyses were carried out with Stata15 for Windows. Firstly, the predictive capacity of GD severity (according to DSM-5 criteria) and UPPS-P impulsivity levels on relapse during CBT treatment, dropout during CBT and dropout in completing patients at the 24-month follow-up was assessed with binary logistic regression adjusted for the patients’ age. These models were adjusted into two blocks: a) first block entered and fixed the covariate age; b) second block added the predictive independent variables through the ENTER method. The Hosmer-Lemeshow test assessed goodness-of-fit (p >.05 was considered adequate fit), global predictive capacity for the predictive variables entered into the second block was assessed through the changes in Nagelkerke’s pseudo-R2 coefficient (ΔR2), and the global discriminative capacity of the final model was estimated via the area under the ROC curve (AUC).

Comparison between UPPS-P scores at baseline between the categorical GD severity groups (using DSM-5 criteria) was based on analysis of variance (ANOVA), adjusted for the participants’ age, including pairwise comparisons to assess differences between the groups.

Finally, survival analyses measured the time to dropout and the first relapse during the CBT intervention, as well as the comparison of the GD severity groups at baseline. This study obtained the Kaplan-Meier (product-limit) estimator and used the Cox’s regression adjusted for the participants’ age to compare the survival cumulate curves between the three GD severity groups (i.e. mild, moderate, and severe). The survival function is a method used to measure the probability of patients “living” (surviving without the presence of the outcome, in this study without dropout and without the presence of gambling relapses) for a certain amount of time after the intervention. One of the most relevant advantages of this procedure is that it allows for the modeling of censored data, which occurs if patients withdraws from the study [Reference Aalen, Borgan and Gjessing48, Reference Singer and Willett49].

3. Results

3.1 Description of the sample

The mean age of the study sample was 41.5 years (SD = 13.1), the mean age of GD onset was 28.5 years (SD = 10.8), with a mean duration of 6.5 years (SD = 6.4). Table 1 includes a complete sociodemographic and clinical description of study sample.

Table 1 Sample description (n = 398).

Note. SD: standard deviation. Cronbach’s alpha in the sample. SOGS: South Oaks Gambling Screen.

3.2 Predictive capacity of GD severity and impulsivity levels treatment outcome

The number of participants who dropout during the CBT program was n = 182 (risk of dropout equal to 45.7%; 95% confidence interval, 95%CI: 40.8% to 50.6%) and the participants who reported gambling episodes during the course of the treatment was n = 119 (risk of relapses: 29.9%; 95% CI: 25.4% to 34.4%). The attrition from treatment completion to the 24-month follow-up was high (risk of dropout during the 2 years follow-up equal to 89.8%: 95%CI: 85.8% to 93.8%). Table 2 includes the binary logistic regression models assessing the predictive capacity of baseline GD severity (the number of DSM-5 criteria) and UPPS-P impulsivity levels on treatment outcome (all the models are adjusted for the covariate age). All models in this table obtained good fitting indexes (p >.05 in the H-L test).

Table 2 Predictive capacity of DSM-5 GD severity and the UPPS-P scores on treatment outcome (second block of the regressions adjusted for age).

Note. 1Model for patients who finished CBT treatment (n = 216).

ΔR2: increase in the Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2 comparing blocks 1 and 2. H-L: Hosmer and Lemeshow test (p-value). AUC: area under the ROC.

* Bold: significant parameter (.05 level). Italics: coefficients for the covariate age. (Sample size: n = 398).

The risk of drop out during the CBT program (the first model in Table 1) was higher for participants who reported higher lack of perseverance and sensation seeking scores. The risk of having a gambling episode (relapsing) during CBT treatment was higher for participants with higher negative urgency levels (the second model in Table 2). Finally, the risk of drop out during the two-year follow-up after the CBT program (the third model in Table 2, obtained for the subsample of patients who finished CBT treatment therapy without dropout) was increased for patients who reported higher scores in sensation seeking.

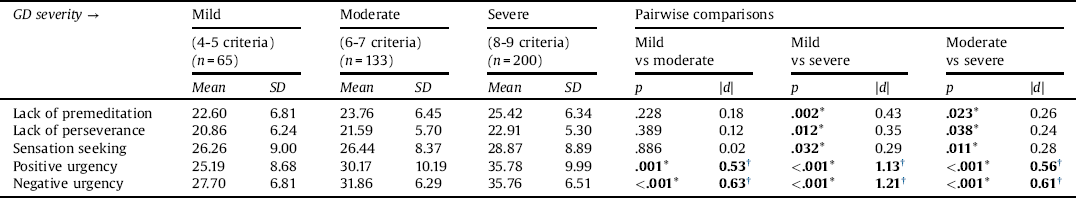

3.3 Comparison of UPPS-P impulsivity levels between DSM-5 GD severity groups

Table 3 includes the ANOVA comparison, adjusted for age, comparing baseline UPPS-P impulsivity levels between the three GD severity groups (mild, moderate, and severe) (Table S1, Supplementary material, includes comparisons for additional clinical measures of these groups). As a whole, mean positive and negative urgency levels increased with GD severity.

Table 3 Comparison of UPPS-P scores based on DSM-5 GD severity categories: ANOVA adjusted for patients’ age.

Note. SD: standard deviation. *Bold: significant comparison (.05 level).

† Bold: effect size into the moderate (|d|>0.50) to high range (|d|>0.80).

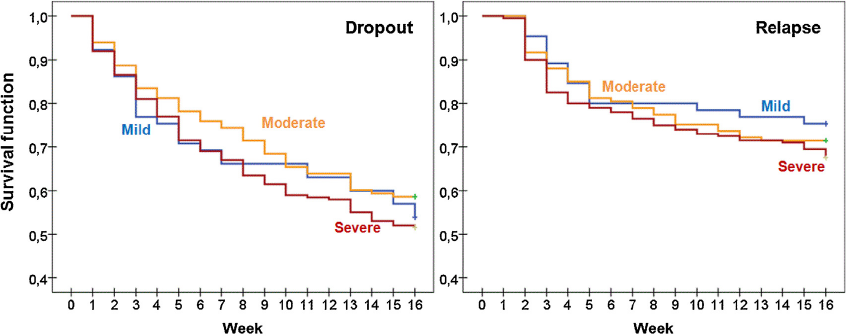

3.4 Survival analysis comparing DSM-5 GD severity groups

Fig. 1 contains the survival function estimated with the Kaplan-Meier method for the rate of dropout and relapses during the CBT program, stratified by DSM-5 gambling severity group (mild, moderate and severe). No statistical differences for these outcomes were found comparing the three groups: Cox’s regression adjusted for the participants’ age obtained χ2-wald = 0.02, df = 1, p =.892 for dropout and χ2-wald = 0.02, df = 1, p =.892 for relapses.

Fig. 1. Cumulative survival functions for dropout and relapse during the 16-week CBT program.

4. Discussion

The present study estimated, in a sample of male patients seeking treatment for GD, the predictive capacity of impulsivity traits and gambling severity on treatment outcome, namely considering relapse and dropout. We also sought to examine the associations between impulsivity, GD severity and treatment response.

Regarding the predictive model, sensation seeking was a predictor of dropout, both during treatment and in follow-up stages. To date, there is a paucity of scientific literature analyzing the association of this construct with GD treatment outcome. However, previous studies in the field suggest that patients with high levels of sensation present a clinical phenotype that could interfere with adherence to treatment guidelines [Reference Merkouris, Thomas, Browning and Dowling37, Reference Billieux, Lagrange, Van der Linden, Lançon, Adida and Jeanningros50, Reference Ramos-Grille, Gomà-i-Freixanet, Aragay, Valero and Vallès51]. These patients may be especially motivated at the start of treatment to become involved in a treatment program with the expectation of receiving the benefits of abstinence, but this interest in the novelty of treatment often quickly fades due to their personality profile [Reference Kahler, Spillane, Metrik, Leventhal and Monti52]. Relatedly, lack of perseverance was another predictor of dropout during treatment and in the follow-up period. Other addiction studies have provided similar evidence, finding that treatment completers had significantly higher persistence levels than those who abandon therapy [Reference Foulds, Newton-Howes, Guy, Boden and Mulder53].

Finally, negative urgency was identified as a predictor of relapse during treatment in the present study. This finding broadly supports the results of other studies in addictions linking high levels of impulsivity with short-term and mid-term relapses [Reference López-Torrecillas, Perales, Nieto-Ruiz and Verdejo-García54]. More specifically, negative urgency has been associated with poorer therapy outcomes [Reference Hershberger, Um and Cyders55] and greater relapse risk. This leads us to postulate that patients with GD are more vulnerable to making rash decisions when experiencing negative mood states, such as frustration or anxiety, leading to more frequent relapses. Gambling behavior, in these cases, is therefore likely used as a means of negative reinforcement in order to regulate affective states. Moreover, it is known that in GD, as the disorder progresses, behavior is increasingly maintained by a pattern of negative reinforcement than positive reinforcement [Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain56]. Therefore, impulsiveness could arise from seeking out relief from negative emotional states rather than from a need to obtain immediate reward [Reference Blanco, Potenza, Kim, Ibáñez, Zaninelli and Saiz-Ruiz57]. From a phenomenological perspective, it is feasible that disinhibition plays a mediating role between these two dimensions [Reference Bottesi, Ghisi, Ouimet, Tira and Sanavio58, Reference Chamberlain, Stochl, Redden, Odlaug and Grant59], with numerous studies suggesting that inhibition is impaired in some patients with GD and that disinhibition, in turn, can be a risk factor for relapse [Reference Goudriaan, Oosterlaan, De Beurs and Van Den Brink60, Reference Goudriaan, Oosterlaan, De Beurs and Van Den Brink61].

Another finding to emerge from the present study is the difference in urgency levels bearing in mind DSM-5 severity categories (mild, moderate and severe). Specifically, the present data uphold the position that in those cases in which the severity of GD is greater, levels of urgency are also higher. This observation dovetails with other research that found that impulsivity was a predictor of GD severity and poor prognosis [Reference Leblond, Ladouceur and Blaszczynski62, Reference Slutske, Caspi, Moffitt and Poulton63].

Although other studies have associated greater GD severity with poorer response to treatment [Reference Merkouris, Thomas, Browning and Dowling37], our study failed to indentify differences in treatment response using DSM-5 GD severity categorizations. The DSM-5 provides nine diagnostic criteria for GD and it is pre-assumed that all criteria have an equal diagnostic impact [Reference Sleczka, Braun, Piontek, Bühringer and Kraus31]. One of the drawbacks of this dichotomous approach is that factors, such as the frequency and the level of distress brought about by gambling behaviors [Reference Grant, Odlaug and Chamberlain29, Reference Chamberlain, Stochl, Redden, Odlaug and Grant59]. Our findings raise further questions regarding the clinical validity of merely summing the number of criteria endorsed by an individual and whether DSM-5 GD severity categories accurately reflect actual GD symptom severity, if each is weighted equally. In the line of the study by Bottesi et al. [Reference Bottesi, Ghisi, Ouimet, Tira and Sanavio58], future studies should consider contrasting dimensional measures with DSM-5 categories in order to determine which best serves as a predictor of treatment response. Doing so could aid clinicians in shifting away from categorical definitions of gambling and allow for more tailored treatment programs that bear in mind the patients’ individual features that place them at greatest risk.

4.1 Limitations

The present study is not without its limitations. First, all data were collected from men who sought treatment and future studies would benefit from including women with GD. Second, impulsivity traits were assessed using self-report measures that are, in all likelihood, unable to fully capture the multi-factorial nature of impulsivity in GD patients. Third, our study only examined the effectiveness of one type of intervention and it would be useful to know if similar results are present using a multiple-arm study design [Reference Bücker, Bierbrodt, Hand, Wittekind and Moritz64]. Finally, it would have been of interest to take pharmacotherapy into account, being that GD patients frequently show comorbidities with other disorders (e.g. depression, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) and that the use of medications could potentially have influenced impulsivity levels.

5. Conclusions

This study aimed to identify short- and long-term predictors of response to treatment in sample of treatment-seeking patients with GD. In concordance with other studies, our findings indicate that increased sensation-seeking levels were a predictor of abandoning treatment, along with greater lack of perseverance scores. Furthermore, we found that greater negative urgency scores increased the risk of relapsing during the 16-week CBT treatment program. However, contrary to our initial hypothesis, increased severity, as categorized by the DSM-5, was not indicative of poorer response to treatment. These results raise doubts with respect to the clinical utility of such severity categories and support the use of dimensional approaches in future studies.

Declarations of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

Financial support was received through the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad (grant PSI2011-28349 and PSI2015-68701-R). FIS PI14/00290, FIS PI17/01167, and 18MSP001 - 2017I067 received aid from the Ministerio de Sanidad, Servicios Sociales e Igualdad. CIBER Fisiología Obesidad y Nutrición (CIBERobn) and CIBER Salud Mental (CIBERSAM), both of which are initiatives of ISCIII. GMB is supported by a predoctoral AGAUR grant (2018 FI_B2 00174), co-financed by the European Social Fund, with the support of the Secretaria d’Universitats i Recerca del Departament d’Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya. MLM, TMM and CVA are each supported by a predoctoral the Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (FPU15/0291; FPU16/02087; FPU16/01453).

Appendix A Supplementary data

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.09.002.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.