Introduction

Emerging infectious diseases that are known to spread through the live animal trade are implicated in species extinctions and declines in amphibian populations worldwide (Daszak et al. Reference Daszak, Cunnigham and Hyatt2000, Fisher & Garner Reference Fisher and Garner2007, Picco & Collins Reference Picco and Collins2008). In particular, chytridiomycosis, caused by the fungal pathogens Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and Batrachochytrium salamandrivorans, along with Ranavirus, have been identified as threats to global amphibian biodiversity (Gray et al. Reference Gray, Lewis, Nanjappa, Klocke, Pasmans and Martel2015). Declines in amphibian populations are concerning because amphibians provide a range of values to humans including cultural significance (Ali et al. Reference Ali, Javid, Hussin and Bukhari2017), environmental services (West Reference West2018) and medicinal products (West Reference West2018, Crnobrnja-Isailović et al. Reference Crnobrnja-Isailović, Jovanović, Čubrić, Ćorović, Gopčević, Ozturk, Egamberdieva and Pešić2020).

Human visitation to natural areas for recreation and other activities is believed to be contributing to the spillover of amphibian pathogens from captive to natural populations (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Rocliffe, Haddaway and Dunn2015). Pathogen spillover into nature can occur through the release of infected animals or contaminated fomites (Peel et al. Reference Peel, Hartley and Cunningham2012) and the movement of virus particles on vehicles, recreational equipment, clothing and footwear (Miller & Gray Reference Miller and Gray2009). Once established in nature, eradication is extremely challenging if not impossible (Fisher et al. Reference Fisher, Henk, Briggs, Brownstein, Madoff and McCraw2012).

Basic protocols and disinfection procedures have been developed for preventing the transmission of pathogens during outdoor activities. Recommended practices include rinsing any gear, clothing or equipment potentially exposed to contaminated water with biodegradable soap and disinfectant (e.g., bleach solution) after use and prior to changing locations or leaving the area (Horner et al. Reference Horner, Miller and Gray2016). However, the effectiveness of these best practices in preventing pathogen spillover in natural areas will depend in part on their rate of adoption by visitors.

Past studies have examined factors influencing natural area visitors’ behavioural intentions to adopt environmentally responsible behaviours (e.g., Brown et al. Reference Brown, Ham and Hughes2010, Kil et al. Reference Kil, Holland and Stein2014, Gill et al. Reference Gill, McKiernan, Lewis, Cherry and Annunciato2020). Using social-psychological models such as the theory of planned behaviour (TPB), these studies have generally sought to identify antecedents to environmentally responsible behaviours by examining individuals’ attitudes, values, beliefs and perceived norms related to the conservation issue and behaviour(s) in question. To date, examination of the willingness of natural area visitors to adopt measures to prevent pathogen spillover or the characteristics that predict their behavioural intentions regarding biosecurity is lacking. As land managers formulate strategies to protect native amphibian populations, understanding the characteristics of natural area visitors and the extent to which they influence visitor behaviour is critical. Education and communication programmes can be a valuable tool for addressing wildlife disease management (Muter et al. Reference Muter, Gore, Riley and Lapinski2013); however, influencing visitors’ actions requires an understanding of the psychosocial factors (i.e., knowledge, attitude, values) that influence their behaviours.

This study’s specific objectives were to: (1) understand natural area visitors’ knowledge, attitudes, perceptions and values regarding amphibian biodiversity, pathogen threats and actions to prevent the infection of amphibians in natural areas; and (2) evaluate the influence of psychosocial factors and socio-demographic characteristics on natural area visitors’ behavioural intentions to take actions to prevent the infection of amphibians in natural areas.

Methods

Study sites

This study was conducted in two natural areas (the Great Smoky Mountains National Park (GSMNP) and Highland Biological Station (HBS)) in the southern Appalachian Mountains of the eastern USA, a global hotspot of amphibian biodiversity. Straddling the ridgeline of the Great Smoky Mountains along the North Carolina–Tennessee border, the GSMNP contains over 2000 km2 of forests, 1300 km of back country trails and over 3000 km of streams and tributaries (National Park Service 2022). The GSMNP is one of the largest protected areas in the eastern USA; with over 14 million visitors in 2021, it is also the USA’s most visited national park (National Park Service 2022). Characterized by its high diversity of amphibians (31 salamander species and 13 frog species), the GSMNP has been designated both a United Nations World Heritage Site and an International Biosphere Reserve (Dodd Reference Dodd2003).

The HBS is a 9.3ha installation of Western Carolina University dedicated to fostering regionally focused outdoor education and research. Situated at an elevation of 1200 m near the crest of the Blue Ridge Mountains in the Appalachian Mountain Range in an area notable for the diversity of its plant and animal life (Ricketts et al. Reference Ricketts, Dinerstein, Olson and Loucks1999), the HBS nature centre and botanical garden attract daily visitors from the surrounding areas, primarily for recreational and educational purposes.

Widespread declines in amphibians have been reported in the Appalachian Mountain region since the 1970s (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Pauley, Withers, Roble, Miller and Braswell1999, Corser Reference Corser2001, Muletz et al. Reference Muletz, Caruso, Fleischer, McDiarmid and Lips2014). Corser (Reference Corser2001) reported that of the 71 species of amphibians that inhabit the five-state region of the Appalachian Mountains almost half were listed as being of conservation concern by federal, state and Natural Heritage programmes in all or a portion of their ranges regionally. Identified threats include habitat loss, collection for the wildlife trade, acid precipitation and introduced species, including harmful pathogens (Mitchell et al. Reference Mitchell, Pauley, Withers, Roble, Miller and Braswell1999, Corser Reference Corser2001).

Survey design and administration

Data were collected by administering an on-site survey to GSMNP and HBS visitors. The anonymous and voluntary survey instrument and protocols were approved by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville institutional review board for human subject research (approval #: IRB-21-06428-XM). Participants were given a small incentive (e.g., drink koozies, sunglasses straps printed with the UT One Health Initiative logo). From June to September 2021, 1494 visitors at three different locations in the GSMNP and one location in the HBS in Highlands, NC, completed the survey.

Measurement of variables

Survey questions assessing knowledge, attitudes, perceptions and values regarding amphibian biodiversity, pathogen threats and actions to prevent the infection of amphibians in natural areas followed Azjen’s (Reference Ajzen1991) TPB, which offers a well-established model for influencing human behaviour through persuasive communication. According to the TPB, three types of cognitive structures determine individuals’ behavioural intentions: (1) their evaluation (favourable or unfavourable) of the behaviour under consideration (ATTITUDE TOWARD BEHAVIOUR) (2) their perceptions of social standards regarding the behaviour (SOCIAL NORMS); and (3) the perceived difficulty of performing the behaviour (PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL; Ajzen Reference Ajzen, Kuhl and Beckmann1985). The TPB has been used widely in studies to predict and explain the willingness of tourists and natural area visitors to engage in pro-environmental behaviours (e.g., Howe et al. Reference Howe, Medzhidov and Milner-Gulland2011, Untaru et al. Reference Untaru, Epuran and Ispas2014, Miller et al. Reference Miller, Merrilees and Coghlan2015, Gill et al. Reference Gill, McKiernan, Lewis, Cherry and Annunciato2020) and to develop persuasive messaging to influence their behaviour (e.g., Brown et al. Reference Brown, Ham and Hughes2010). Survey questions related to respondents’ ATTITUDE TOWARD BEHAVIOUR, SOCIAL NORMS and PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL were rated on a five-point Likert scale of agreement (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree) using various statements that represented the corresponding constructs (Table 1). ATTITUDE TOWARD BEHAVIOUR was elicited with the statement ‘Protecting natural populations of amphibians from disease is important to humans’, whereas SOCIAL NORMS and PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL were elicited with the statements ‘People important to me (e.g., family, friends) favour conserving amphibians’ and ‘It is not difficult for me to take preventative actions (e.g., cleaning shoes/gear, avoiding direct contact with amphibians in nature) to protect amphibians from possible infection, respectively.

Table 1. Description of the variables used in predicting visitor willingness to take actions to prevent pathogen transmission to natural areas.

The importance of the benefits of amphibian biodiversity to respondents (ENVIRONMENTAL) and the importance of recreation (RECREATION) and ‘experiencing/learning about nature’ (LEARN) as motivations for visiting the survey site were rated on five-point Likert scales of importance (1 = not at all important; 5 = extremely important). Visitor willingness to rely on responsible wildlife and land managers to protect amphibians from pathogens (TRUST) and visitor perceptions toward the risk of human-mediated pathogen transmission (THREAT) were rated on five-point Likert scales of agreement (Table 1). Willingness to take action (the dependent variable in our regression model; WILLING) was elicited with the statement ‘I am willing to take disinfecting actions (e.g., cleaning shoes/gear) and avoid direct contact with amphibians in nature to prevent infection of amphibians in natural areas’ and was rated on a five-point Likert scale of agreement.

Regression model

In order to meet Objective 2 of this study, an ordinary least squares (OLS) multiple linear regression model was estimated using the variables ATTITUDE TOWARD BEHAVIOUR, SOCIAL NORMS, PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL (e.g., Martin & McCurdy Reference Martin and McCurdy2009, Brown et al. Reference Brown, Ham and Hughes2010, Wang et al. Reference Wang, Zhang, Yu and Hu2018), TRUST, THREAT (Episcopio-Sturgeon & Pienaar Reference Episcopio-Sturgeon and Pienaar2020, Pienaar et al. Reference Pienaar, Episcopio-Sturgeon and Steele2022) and ENVIRONMENTAL (Gill et al. Reference Gill, McKiernan, Lewis, Cherry and Annunciato2020), which, based on the literature, we predicted would be significantly positively associated with willingness to take action (WILLING). We had no a priori expectations regarding the direction or significance of the remaining explanatory variables (RECREATION, LEARN, FEMALE, INCOME and HOUSEHOLD). The significance of the regression parameter was determined based on the criterion of p ≤ 0.05.

Results

Knowledge of amphibians and attitudes toward pathogen threats and preventative actions

A total of 80% of respondents reported being familiar with general knowledge regarding amphibians, 70% reported being familiar with the role of amphibians in the environment and 57% and 46%, respectively, reported being familiar with the benefits of amphibians to humans and the status/trends of amphibian populations (Fig. 1). When asked how often they engage in amphibian-related activities (e.g., searching, viewing, learning, photographing) while visiting natural areas, 55% reported sometimes, while 16% and 5% reported frequently and regularly, respectively. Nearly all reported environmental benefits, aesthetic and medicinal/pharmaceutical values, scientific and educational value and controlling harmful insects as important.

Fig. 1. Respondents’ reported familiarity with various aspects of amphibians including general knowledge about amphibians (n = 1491), role of amphibians in the environment (n = 1486), benefits of amphibians to humans (n = 1488) and status/trends of amphibian populations (n = 1486).

A total of 58% of respondents agreed that the transmission of pathogens to amphibians is a serious threat in the natural areas they often visit, while 85% indicated protecting natural populations of amphibians from disease is important. A total of 66% of respondents agreed that people important to them favour conserving amphibians (Table 2). Over 80% of respondents indicated it was not difficult for them to take actions to protect amphibians from infection, and they were willing to take actions (WILLING) to prevent the infection of amphibians in natural areas. Approximately 86% of respondents indicated that they trusted wildlife/land managers to take appropriate actions to protect amphibians from pathogens.

Table 2. Means of the variables included in the regression model of visitor willingness to take actions to prevent pathogen transmission to amphibians in natural areas.

Factors influencing visitors’ willingness to take actions to prevent pathogen spillover

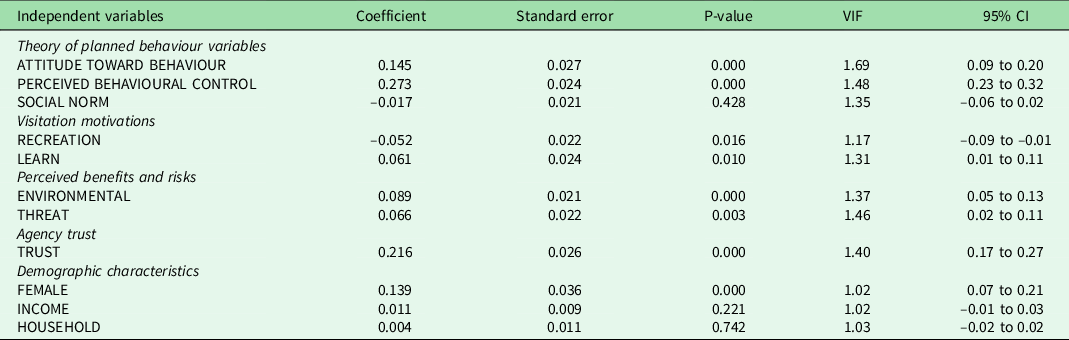

The regression model’s overall fit to the data was good (adjusted R2 = 0.38, df = 1356, p < 0.001; Table 3). The variance inflation factor values confirm that multicollinearity was not an issue in the multivariate model. Among the three key explanatory variables per the TPB, ATTITUDE TOWARD BEHAVIOUR, which represents the degree to which respondents held a favourable attitude toward taking actions, and PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL, which characterizes the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the actions, were positively associated with WILLING (both p < 0.01). Contrary to our expectation, SOCIAL NORMS (i.e., respondents’ perception of the norms and conventions regarding the actions) was not significantly associated with WILLING.

Table 3. Regression results of protected area visitors’ willingness to take actions to prevent pathogen transmission to amphibians in natural areas.

CI = confidence interval; VIF = variance inflation factor.

In terms of factors important in respondents’ decisions to visit the natural area where they were surveyed, recreation (RECREATION) was negatively associated with WILLING (p = 0.02), while experiencing/learning about nature (LEARN) was positively associated with WILLING (p = 0.01). Similarly, ENVIRONMENTAL was positively associated with WILLING (p < 0.01), as was THREAT (p < 0.01), representing the extent to which respondents agreed that spillover of pathogens to amphibians is a serious threat in the natural areas they often visit. The regression coefficient on the variable representing respondents’ trust in wildlife/land managers to take appropriate actions to protect amphibians from pathogens (TRUST) was positively associated with WILLING (p < 0.01).

In term of socio-demographic characteristics, FEMALE was positively associated with WILLING (p < 0.01); family size (HOUSEHOLD) and household income (INCOME) were not associated with the respondents’ WILLING. Prior to specification of the final regression model, the influence of survey location on WILLING was found to be insignificant; because its inclusion did not contribute to the explanatory power of the model, survey location was omitted as a covariate from the final regression model.

Discussion

Protecting the biodiversity of natural populations such as amphibians involves engaging visitors in preventative actions, which requires an understanding of their knowledge, perception of threats and intentions to engage in preventative behaviours. This was the first study to assess the extent to which visitors to natural areas care about the health of amphibian populations and threats to amphibian biodiversity and how these relate to their intention to take actions to prevent the infection of amphibians in such areas. Our results suggest a large majority of visitors to natural areas believe that pathogen spillover in such areas is a serious threat and they are willing to take preventative actions. This is not surprising considering that many of these visitors are attracted by the unique natural amenities and care about the conservation of species and the integrity of natural systems. Unlike other protected areas such as wildlife management areas and hunting reserves, national parks do not allow consumptive recreational activities, and the visitors to these natural areas may have more regard for the non-consumptive value of wildlife and protection of species.

ATTITUDE TOWARD BEHAVIOUR was influential in predicting visitors’ willingness to take actions, and elsewhere this has proven to be a significant predictor of behavioural intentions to engage in pro-environmental behaviours (e.g., Brown et al. Reference Brown, Ham and Hughes2010, Untaru et al. Reference Untaru, Epuran and Ispas2014, Miller et al. Reference Miller, Merrilees and Coghlan2015). Gill et al. (Reference Gill, McKiernan, Lewis, Cherry and Annunciato2020) found that visitor doubts as to the efficacy of cleaning to be a major obstacle to compliance with weed hygiene practices in Australia’s Kosciuszko National Park. Thus, messaging emphasizing the effectiveness and importance of biosecurity protocols in preventing pathogen spread may cultivate favourable attitudes among visitors regarding their implementation and the protection of amphibians.

Contrary to our expectations, SOCIAL NORMS was not associated with visitor willingness to take preventative actions while visiting natural areas. Although a multitude of research has shown social norms to be reliable determinants of pro-environmental behaviour (Farrow et al. Reference Farrow, Grolleau and Ibanez2017), the results of the present study imply an absence of perceived social pressure or fear of social exclusion on the part of natural area visitors with respect to the adoption of preventative actions.

The positive effect of PERCEIVED BEHAVIOURAL CONTROL on willingness to take actions suggests that respondents who believed that taking preventative actions was not difficult were more likely to be willing to take actions. Similar studies have found perceived behavioural control to be a significant predictor of individuals’ willingness to engage in environmentally responsible behaviour (e.g., Brown et al. Reference Brown, Ham and Hughes2010, Untaru et al. Reference Untaru, Epuran and Ispas2014, Miller et al. Reference Miller, Merrilees and Coghlan2015), including adopting biosecurity hygiene practices in national parks (Gill et al. Reference Gill, McKiernan, Lewis, Cherry and Annunciato2020). Gill et al. (Reference Gill, McKiernan, Lewis, Cherry and Annunciato2020) found simplicity of compliance as a primary reason for national park visitor compliance with recommended biosecurity hygiene practices. It is thus expected that the provision of strategically sited facilities (e.g., cleaning stations, disinfecting solutions) with easy-to-follow instructions may lead to increased compliance.

Trust in wildlife/land managers to protect amphibians from pathogens was also influential in visitors’ willingness to engage in environmentally responsible behaviour. Although results have been mixed (e.g., Pienaar et al. Reference Pienaar, Episcopio-Sturgeon and Steele2022), various studies have shown that trust in responsible agencies to manage disease risk can have a positive impact on public attitudes toward wildlife and conservation (Watkins et al. Reference Watkins, Poudyal, Jones, Muller and Hodges2021) and can be an important predictor of outdoor recreationists’ behaviour (e.g., Meeks et al. Reference Meeks, Poudyal, Muller and Yoest2022). Messaging to encourage compliance with biosecurity protocols should therefore aim to cultivate credibility and trust among visitors. Emphasizing the GSMNP’s history of successfully conserving protected resources along with the provision and maintenance of sufficient cleaning equipment may help in this regard (Gill et al. Reference Gill, McKiernan, Lewis, Cherry and Annunciato2020).

Consistent with Andereck (Reference Andereck2009) and Kil et al. (Reference Kil, Holland and Stein2014), the motivation of visitors in our study seemed to influence their behaviour. Specifically, visitors with a recreational motivation were less willing to take actions than visitors with an experiencing/learning motivation. These findings suggest that on-site visitor behaviour regarding biodiversity protection may be influenced by the diverse motivations of the increasingly heterogeneous population of visitors to natural areas. Maximizing visitor compliance with enhanced biosecurity protocols will require an awareness of visitor motivations accompanied by strategic communication and outreach encouraging their adoption.

Other than gender, demographic characteristics were not significant predictors of willingness to take actions. Little differentiation may exist between varying socioeconomic groups in terms of their behavioural intentions to take actions to protect amphibians from infection, and thus messaging should rather focus on issues reported as salient by respondents rather than perceived differences based on socio-demographic characteristics (Needham et al. Reference Needham, Vaske and Petit2017, Pienaar et al. Reference Pienaar, Episcopio-Sturgeon and Steele2022).

Pearson’s χ2 tests of independence indicated that GSMNP visitors and HBS visitors differed in terms of their age and the number of individuals in their households, reflecting the fact that the Highlands area is a popular destination in the summer months for retirees and the GSMNP is a vacation destination for families. HBS visitors were also more likely to report experiencing/learning about nature as the motivation for their visit, which is consistent with the focus of the HBS being more on education and research than the GSMNP. There was no difference between GSMNP visitors and HBS visitors in terms of their willingness to take actions.

Natural area visitors can play a key role in amphibian conservation by limiting the likelihood that their actions will lead to pathogen spillover. The findings from this study suggest that natural area visitors are aware of and willing to take action against pathogen threats. Accordingly, the formulation of enhanced biosecurity protocols and strategic messaging aimed at maximizing visitor compliance should emphasize the environmental importance of natural amphibian populations, the threats that pathogens pose and the effectiveness of prescribed practices at preventing pathogen transmission. Managers may also see benefit in making it convenient for visitors to adopt preventative actions either by providing easy-to-follow practices or by offering appropriate facilities/equipment in natural areas that are subject to high visitation levels. As a case study from Appalachia, this study represents a first step in understanding the attitudes and behaviours of natural area visitors with respect to amphibian pathogen threats and enhanced biosecurity protocols to mitigate their spread. Although survey location was not a significant determinant of willingness to take actions in this study, future research examining actual rates of compliance among natural area visitors and their perceptions as to the ease and effectiveness of biosecurity protocols across a diverse sample of natural areas could inform programme development, resulting in improved conservation outcomes for native amphibian populations.

Acknowledgements

The input from Jesse Brunner, Julie Lockwood and Molly Bletz in developing the survey instrument is gratefully acknowledged. The authors are also thankful to Smoky Mountain National Park and Highland Biological Station for allowing us to administer our visitor survey and to Victoria Porter and Sarah Payne for their assistance in on-site survey administration.

Financial support

Funding was provided by the joint NSF–NIH–NIFA Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Disease award IOS 2207922 and University of Tennessee One Health Initiative.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

This study was approved by the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s institutional review board for human subject research (approval #: IRB-21-06494-XM).