Pioneered by Ele.me (Eleme 饿了么) in 2008, China's food-delivery platforms have since expanded rapidly to become the largest in the world. Nearly half of China's internet users placed orders in 2021, accounting for 21.4 per cent of the country's catering sector's total revenue.Footnote 1 More than 6.2 million couriers deliver food for Meituan (Meituan 美团) and 1.14 million deliver for Ele.me.Footnote 2 Their working conditions have become a cause for concern in society and among policymakers. There are two dominant issues: the frequent accidents involving couriers, which are caused by strict service deadlines, as revealed by a series of reports in September 2020,Footnote 3 and the couriers’ legal status with regards to whether they are platform employees or not.Footnote 4 The couriers themselves, however, receive less attention; their voices are rarely heard, in stark contrast to the collective struggles of Chinese factory workers and their influence on recent laws.Footnote 5

Strikes are widely regarded as the most disruptive manifestation of labour–capital conflict as well as being a major social problem.Footnote 6 In China, they are considered to be particularly controversial and even politically alarming.Footnote 7 Traditionally, strikes are linked to the manufacturing industry, but they also occur on platforms. As chronicled by the media and examined in the literature, Uber driver strikes are not uncommon, and there have been courier actions in Britain (Deliveroo), in Italy (Foodora) and occasionally in China (Meituan and Ele.me).Footnote 8 Examining how and why Chinese platform workers strike is the key to understanding the country's new labour politics and a distinctive case in the world's emerging platform economy.

There are two major employment models within the platform economy: crowdsourcing and outsourcing. To date, most reported strikes in China and elsewhere have been large-scale and high-profile actions organized by crowdsourced workers. Although crowdsourcing may dominate most Western platforms, outsourcing is widespread on China's delivery and ride-hailing platforms.Footnote 9 In China, the outsourced (zhuansong 专送) and crowdsourced (kuaisong 快送) couriers perform similar work and are not employees of the platform, but there are key differences. Crowdsourced couriers have the autonomy to choose whether, when and where to work, and their connections with the platforms are loose and entirely virtual, mainly via smartphone apps. In contrast, outsourced workers are tied to a physical station, deliver within a 2.5 to 3.5 km radius, mostly work full-time with regular schedules, and interact with their station supervisors every day. Thus, outsourced couriers are managed by their virtual platform and their agency's human supervisors (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Management of Different Employment Models

Initially, Chinese food-delivery platforms hired their own couriers. Fierce competition for the market and financial capital fostered the advent of crowdsourcing, and an “asset-light” principle drove the platforms to reduce their labour costs by outsourcing or subcontracting to external agencies. By 2019, Meituan and Ele.me dominated the food-delivery market, and most couriers were either outsourced or crowdsourced. Outsourced couriers account for 40 per cent of the total workforce on these platforms. They offer more reliable delivery times, a higher-quality service and receive double the monthly average number of orders as crowdsourced couriers. Thus, outsourced workers are considered to be “stickier labour” than crowdsourced couriers and indispensable for China's food-delivery platforms.Footnote 10

How does this outsourcing model impact workers’ collective actions? Among previous crowdsourcing-focused studies, a few notable exceptions have analysed control and resistance in China's outsourcing platforms.Footnote 11 One comparative study of service (outsourcing) platforms and gig (crowdsourcing) platforms suggests that compared to gig couriers, outsourced workers view strikes as less attractive.Footnote 12 However, another study argues that outsourced couriers could easily engage in strikes.Footnote 13 Our study presents a more nuanced and intriguing view: strikes by outsourced couriers are surprisingly frequent but largely invisible to outsiders.

This study explores the unique features and causes of couriers’ resistance on Chinese outsourcing platforms. After reviewing the literature on platform work and collective action, this study adopts the work regime approach, which it supplements with an analysis of workers’ bargaining power, to examine the platform dynamics under current state interventions. Specifically, it explores the ongoing policy changes, the platforms’ dual management structure, and the induced labour–capital tension, power and tactics at the bottom. In-depth case studies based on extensive fieldwork reveal the complexity of outsourced couriers’ resistance. This study argues that the outsourcing platforms have created a regime of “contentious despotism” that is primarily despotic, although it has some hegemonic consent on the ground. This despotic regime is contentious and frequently resisted by workers who possess bargaining power that they actively utilise, at least sometimes. Although short-lived, quickly covered up and as yet to affect policy, labour resistance is frequent and has the potential to endure.

Labour Platforms and Collective Action

Many studies on the platform economy have examined these new businesses and their labour conditions. Platforms take diverse and malleable forms.Footnote 14 Each platform digitally connects multi-sided markets and organizations by matching supply and demand, allocating work and evaluating performance.Footnote 15 They constantly accumulate data and adjust algorithms, adopting “the lean startup methodology and management by metrics” to evolve the platform operations.Footnote 16

What follows the platforms’ evolution is the degradation of work. The literature has typically described location-specific, low-skill labour platforms, such as for ride-hailing and delivery services, as an “accelerant of precarity” or a “digital cage.”Footnote 17 The concern is that these platforms increase workers’ precarity by further weakening standard employment. Platform workers perform short-term, low-paid tasks without labour protection.Footnote 18 Moreover, workers are confined by the multi-faceted digital control exercised by the platforms. In an environment of asymmetric information, the platforms make explicit rules that interfere with work arrangements and exchanges, set prices and apply surveillance mechanisms.Footnote 19 Another form of digital control is data-driven gamification. Platform work is constructed by design to appear game-like, but the aim of capital is to manipulate a flexible labour supply for higher productivity.Footnote 20 Digital control seems “softer,” but it is greater than the control exercised in traditional industries,Footnote 21 and workers’ freedom and job flexibility are either illusory or a mere disguise.Footnote 22

Although these conditions cause dissatisfaction, active labour solidarity is not always possible. When the platforms exercise concentrated power, workers have less autonomy or mutuality.Footnote 23 Platforms’ multi-faceted control is meant to increase productivity and destroy labour solidarity. When faced with fierce competition or decreasing pay rates, most gig workers respond by working longer hours and giving up the freedom that first attracted them to the platform.Footnote 24 The lack of effective interpersonal connections that can build the necessary trust for solidarity discourage them from acting.Footnote 25 Thus, some studies have argued that technological control and labour atomization disempower platform workers.Footnote 26

Nevertheless, some workers do act. Historically, labour resistance has always followed capital exploitation,Footnote 27 and new management controls have been challenged by labour, forming “contested terrains” in the workplaces.Footnote 28 Now, workers attempt to evade digital surveillance or to outsmart the algorithm, which leads to the varied efficacy of such control and monitoring tactics.Footnote 29 Strikes also occur.Footnote 30 Some workers have become conscious of their shared interests and have begun to organize themselves.Footnote 31 For example, to mobilize their co-workers, Uber drivers and Amazon Mechanical Turkers have taken to social media, messaging apps and online forums to express their grievances and discuss potential responses.Footnote 32

However, most studies of platforms have not considered whether the employment models matter for labour resistance. It is especially important for China where the outsourcing model, compared to crowdsourcing, is essential for deliveries. With all of their new business and technological features, outsourcing platforms continue to rely on the offline physical stations established by external labour agencies and the stations’ human supervisors to manage workers. This mixture of new business design, old labour practice, digital control and human management makes the outsourcing platforms particularly unsettled workplaces.

This situation was evidenced by two recent studies on China that showed divergent trajectories of outsourced labour contention. The first study argued that outsourced workers were less likely to strike than crowdsourced couriers by comparing the architecture of the outsourcing and crowdsourcing platforms.Footnote 33 Although both models involved the exercise of technological control and could generate grievances, the legal and organizational dimensions of crowdsourcing escalated those grievances, made workers feel exploited and eventually increased the likelihood of a strike. In contrast, the outsourcing platforms, through labour contracts and human supervision, contained grievances and thus reduced workers’ willingness to strike. The second study showed how easily outsourced or subcontracted couriers engaged in quiet, small-scale strikes that targeted the platforms’ sub-contractors, and discussed the political implications of that situation.Footnote 34 This divergence highlights the difficulties of statistically calculating the frequency and influence of real-world strikes.Footnote 35 Political constraints in China also result in incomplete data: online posts on social media are quickly deleted and the news, often from overseas, merely covers large-scale strikes, which were a data source for the first study. On a practical level, outsourced workers’ strikes, typically small in scale, are omitted from official statistics and are rarely in public view. Further research is needed to understand outsourced couriers’ resistance.

A Work Regime Approach

To explain the myth of frequent yet invisible episodes of labour resistance on the outsourcing platforms, this study draws on the labour sociology, industrial relations and platform economy scholarship. The framework of the study is the work regime approach, which examines labour–capital relations at the point of production. The term “work regime” has a similar meaning to a production regime or factory regime, but it is more appropriate for food-delivery platforms, which do not directly involve a factory or production. This approach helps to demonstrate how and why these workers resist. Moreover, considering the invisibility of such labour resistance, this study also analyses workers’ bargaining power to understand the leverage that enables them to resist and to explore the potential of such resistance.

The work regime concept has broad connotations, but the central idea is that the struggles of the working class, rather than being natural or inevitable, are shaped by the production process. Originally, the concept of a production regime positioned the labour process analysis within a broader picture of structural conditions: the state and factory apparatuses.Footnote 36 Together, state interventions and market forces, centred on the factory, give rise to different types of production regimes in which workers may either be coerced or consent to capital. In the 1970s, Michael Burawoy asked “why workers don't resist”; he answered that a “hegemonic” regime in which state legislation on social insurance, union mechanisms and workplace interactions during the production process resulted in prevailing consent between labour and capital. In other settings featuring state interventions that are less effective or even separate from the factory, management's overtly coercive disciplinary regulations and workers’ wage dependence may form a typical “despotic” regime.Footnote 37

Many studies have applied this approach to Chinese factories. When the planned economy was dismantled, “disorganized despotism” emerged in the 1990s, featuring coercive control by management and the collective inaction of workers under chaotic reform policies.Footnote 38 A more recent study described the proliferation of production regimes, classifying dozens of factories into five types depending on their relations with the state, the industrial and production organization, and labour–management interactions.Footnote 39 Frequent strikes in Chinese factories also draw scholarly attention. In the case of Shenzhen city, where labour protests prevailed, a new form of “contested despotism” arose. Factory workers protested to safeguard their interests at the workplace and to influence labour law and enforcement.Footnote 40

This study adjusts the above-referenced approach to analyse the platform economy. The specific conditions of the new sector should be considered. First, the work regime on the platforms is based on the employment model, rather than being single firm- or location-based, as in factory-centred studies. Each platform is a network of multiple organizations. The major food-delivery platforms in China are similar in their businesses, technology, workforce composition and organization. All of the platforms in the sector use both outsourcing and crowdsourcing. These different employment models cause distinctive surplus-sharing and power relations among the multiple firms on the platforms, shaping labour practices and relations. Thus, rather than analysing a specific firm, location or platform, this study analyses the work regime of a major employment model: outsourcing.

Second, analysis of workers’ bargaining power supplements the work regime approach. This study asks the question: why do workers resist even though it appears they do not? While production regime studies have typically responded to “why not resist,” the factors contributing to labour resistance have not been sufficiently considered. It has always been debated whether platform workers are disempowered on the new platforms, which lack established unionism. Thus, outsourced couriers’ bargaining power is analysed. Theoretically, workers have structural bargaining power and associational bargaining power.Footnote 41 Workers gain associational power by allying, and they may also derive power from structural factors such as an insufficient labour supply in the market, strategic position in the workplace and strong protective institutions.

For the above reasons, this study adopts the work regime approach to systematically examine the state and “factory” (the outsourcing platform) apparatuses using Burawoy's terminology. The state's interventions in the platform economy, including the policies and trade unions, and their effects on labour practices are discussed first. Given the current state interventions, the outsourcing platforms are investigated for their organizational design and the relations between their different units. This is followed by an analysis of workers’ bargaining power under such business and management arrangements. Eventually, all of these structural factors work on the ground to shape the grassroots management tactics and workers’ responses. A detailed record of the labour–management dynamics is provided to demonstrate the complexity of labour resistance on outsourcing platforms.

Research Methods

This study, which is based on participatory observation and in-depth interviews, seeks to grasp the relationships and dynamics among multiple actors – the platform firms, the restaurants, the agencies, their stations and supervisors, and the workers. The complexity of the issues under study requires nuanced explanations that are best acquired through the “holistic and real-world perspective” of case studies.Footnote 42 The main questions include the following. First, what causes labour grievances? Second, why do some labour grievances develop into strikes while others do not? Third, how can a strike remain unnoticed?

Fieldwork was conducted in two major cities in southern China from July 2019 to June 2021. At first, the authors conducted interviews that explored why outsourced couriers seldom resisted. Author A worked as a courier for 18 months. He applied for the job after seeing an advertisement on his electric bike and started working the next day after completing a simple physical exam. As “insiders,” the authors soon discovered that resistance occurred far more frequently than described in the literature. During the period of observation, at least five strikes occurred in the area, none of which was covered by any media or was publicly acknowledged. The outsourcing model both created and hid many conflicts.

The theoretical sampling method was used. Two restaurants and two coffee stores – M, K, P, L – with store-station couriers were selected. They had all adopted a special type of outsourcing: the store station (zhudian 驻店). The store stations and other outsourced stations differ only in scope and scale. Store-station couriers deliver for a single brand-named store with large and stable orders – for example, companies such as McDonalds, Starbucks or a large supermarket – which demands the highest-quality service. Other station couriers deliver for many restaurants and shops. Moreover, a store station usually has 10 to 40 couriers, but a station can have 40 to 200. In other words, the store-station couriers have more work demands than other station couriers and are part of a smaller and relatively fixed workforce.

The four stores presented the most similar cases. They were branches of popular brands that quickly adjusted their traditional self-delivery services to today's platform economy.Footnote 43 For instance, K started its delivery service in 2006. Today, its customers can order through K's own platform, Meituan or Ele.me. All of the stores delivered food or drinks using outsourced agency labour. However, the couriers in the four stores acted differently – from grudging consent to informal resistance to open action. In 2020, two strike attempts were observed, and one strike actually took place. A detailed comparison reveals the key differences of those actions.

Overall, the authors conducted 60 face-to-face interviews that centred around questions on platform management and labour responses. The interviewees included 50 couriers, four supervisors and six managers from agencies and platforms. To understand the details of the strike in the K store, seven couriers, a supervisor and a store manager were interviewed. Participatory observation was conducted in all of the four stores, but Author A did not join the strike preparations in M and had already shifted to L before the strike occurred in K. Nevertheless, Author A remained in all of the stores’ WeChat groups and kept in close contact with most of the couriers and supervisors. The interviews with couriers were conducted during their breaks and waiting periods, and the supervisors and managers were visited at their stations or offices. The interviews lasted from 20 to 60 minutes. The records were transcribed and briefly coded to generate ideas for analysis. Additionally, the regulations of the platforms and agencies, and online communications between the couriers were collected as supplementary material. To ensure ethical research standards, all of the interviewees were informed of the authors’ identities and all individuals anonymized.

Structure and Power on Outsourcing Platforms

Ineffective state institutions

China's political and legal conditions set the context for the platform economy in which the state and collective labour have remained functionally absent. Following a heated public debate on the problems with platform labour, the state responded rather swiftly with a round of policymaking. A series of national policies went under discussion and were newly issued. The core of these policies wavers between the need for job creation and the need for strict oversight of platform firms. According to Premier Li Keqiang 李克强, the key principle is “tolerant prudence” (baorong shenshen 包容审慎), or “attaching equal importance to delegating power and strengthening oversight” (fangguan bingzhong 放管并重).Footnote 44 These two goals have become particularly difficult to balance because, since 2020, the platforms have offered many jobs to the newly unemployed, for example those laid off from factories or small businesses.

While the oversight of platforms cannot be too strict, the policy solutions to platform labour problems are mostly individualized in the nearly non-union setting. New protective rules centre on encouraging workers to obtain occupational injury insurance and to only sign labour contracts “when the conditions are fit for confirming labour relations.”Footnote 45 The All-China Federation of Trade Unions issued opinions in favour of protecting platform labour, and local unions in many provinces and cities began to attract those workers as members.Footnote 46 However, the official unions, whose status was debatable, maintained an uncontroversial service orientation, such as the provision of water and physical exams for platform workers.Footnote 47 Collective negotiation, although officially mentioned, has not been effectively conducted on platforms.

On the ground, these policies have made little difference owing to the typically long distance between policymaking and enforcement.Footnote 48 In many studies, labour contracts have been a key legal issue.Footnote 49 The outsourced, full-time couriers interviewed during our fieldwork had often signed one-year labour contracts with external agencies that were different from independent contractors’ agreements or service contracts for crowdsourced workers. However, these labour contracts provided no concrete wage information and did not explain any substantial restrictions on either side. Few workers expected the contracts to provide protection, and they would leave their jobs without being held liable for breach of contract. A station supervisor admitted, “it is no use … you cannot restrain couriers with that contract,” although the platforms required all agencies to sign it.Footnote 50 The issue of social insurance was similar. The majority of both the outsourced and crowdsourced workers did not join social security schemes based on their work, nor did they have occupational injury insurance. They only paid for commercial accident insurance as a precondition for their daily work. As of June 2021, existing institutions have still not provided valid non-wage alternatives for workers, nor have they provided any effective buffer of or predictable channel for conflict.

The layered platform structure and its problem

As the state institutions regulating the new economy are still evolving, the platform structure is the key to understanding labour conflict. The design of the outsourcing platforms, which separates business operations from labour management, may be perceived as a long-term capital “strategy” to achieve a cost-effective but quality-reliable operation. However, the implementation of this strategy imposes constraints on the agencies and often causes management difficulties.

The major players in the outsourcing model are the platform firms, the third-party agencies and their local management at the stations or stores, and the couriers. At the top is the platform company, or for the store stations, one branded restaurant corporation and its cooperating platform. The platform designs the framework of delivery services, builds the system and algorithm, and adjusts the procedures, quality standards and piece rates for the agencies. To maintain its reputation, a restaurant wants to deliver food and drink that is as fresh as if the customers were dining in. This puts pressure on the store-station couriers. For instance, many coffee and pizza stores, such as P and L, required couriers to deliver their orders inside of 30 minutes, rather than the 45–60 minutes that was typical for stations and an even longer delivery time for crowdsourcing.

This model has inherent contradictions. Even by shunting their labour functions onto external agencies, the platforms cannot completely avoid managing labour because their performance, such as customer satisfaction and market share, essentially relies on the services provided by the workers. The platforms try to achieve this by virtual control, typically through constantly optimizing algorithms to calculate faster routes, shorten delivery times and lower prices. This requires the platforms’ operating rules to be revised accordingly. Outsourced couriers, although not legally platform employees, are subject to those rules. The problem then arises that when a platform's technological governance attempts to improve efficiency by unilaterally changing its rules, the workers become irritated and cause trouble for management.

In practice, a platform rule change directly affects outsourced couriers, but they have no say over the change. The platforms, entrusted by the restaurants, have rulemaking power and exert virtual control. At the platform level, a delivery is regarded as a calculated process. However, a seemingly small adjustment can greatly change every courier's work. During the investigation period, all of the platforms adjusted their delivery rules to tighten labour control, including providing detailed criteria for store arrivals, pickups and order completion, and explicitly imposing fines for delays, bad comments and consumer complaints. For instance, time restrictions forced many couriers to click “complete” buttons before making an actual delivery; however, under the new rules, doing so became a violation. Additionally, centralized decision making did not always match local conditions. Despite the improving accuracy of global positioning systems and algorithms, the calculations can easily be invalidated by geographical conditions, building types and other local features that cause inconsistencies in delivery data. “No system is perfect,” commented a supervisor.Footnote 51

The outsourcing agencies’ hands were equally tied. Most of these agencies were established for and competed in the platform outsourcing market. With limited profits available under their platform contracts, the agencies plan staffing for each station, allocate resources, and adjust the detailed pay rates and fines for violations. An agency manager explained, “It is a low-margin business. If we have monthly data falling below the platform requirements, the platform will deduct the delivery fee for every order – a few per cent. We lose money if we don't fine couriers.”Footnote 52 The agencies also lacked any conventional infrastructure for labour relations, such as negotiation and dispute resolution, or the resources to build it.

Concerned about potential labour resistance, the platforms pressured the agencies. One platform's “City regulations on agencies” clearly stipulated on the first page that any strike was expressly forbidden and would incur the highest fine along with other punishments. A poster in an agency's office stated that “significant incidents” involving five persons or more, such as waving banners and rioting, must be reported within an hour and resolved “in time.” Collective action was a “high-voltage line” and the burden of warning fell upon the supervisors. Failure to “actively remedy” such actions could not only cost them their own jobs but also jeopardize the agencies’ contracts. As the platforms imposed extensive obligations on, but gave limited authority to, the agencies, the grassroots became a hotbed of conflict, the management of which depended on the skills of the station supervisors.

Workers’ bargaining power

Outsourced couriers lack institutional power owing to the absence of effective state policies or trade unionism. However, they do possess strong workplace bargaining power. Their geographical concentration and social networking, compared to crowdsourcing, are also favourable for mobilizing and organizing. Such informal associational power paves the way for them to organize among themselves and eventually act collectively.

Strong workplace power came from the relatively fixed group of couriers. The number of couriers for each station was meticulously calculated by the agency. It should not be too small because all orders must be properly delivered, but it should not be too big because couriers leave if they only deliver a few orders and earn little. As the number of orders varied according to weather, season, holiday periods and pandemic restrictions, the supervisors tried hard to stabilize the headcount. Consequently, the outsourced couriers were relatively committed and worked in the same station for months. Although their “workplace,” either a station or store, did not function like a factory and they went back and forth between stores and consumers, outsourced couriers shared some physical space while waiting for orders at common points, bumping into one another in limited delivery areas, and resting together outside popular restaurants or convenience stores. Store-station couriers spent a particularly long time inside the store, remarking that “time is money” and “whenever the orders come, we should move – where else do we stay?”Footnote 53

These fast, high-quality services made the delivery process potentially vulnerable. Strict delivery times were part of the fierce competition among platforms. Meituan and Ele.me shortened their delivery times from one hour in 2016, to 45 minutes in 2017 and then to only 38 minutes in 2018. The delivery pace was especially vulnerable to interruptions and delays during peak hours, rainstorms or in the absence of just one courier. A station's high-quality service rating required the retention of experienced couriers who could easily handle spilt drinks, fragile packages and expensive food. For store stations, it was abnormal for couriers from elsewhere to take store orders even during a surge in orders. This contributed to the scarcity or exclusiveness of store-station couriers, unlike the seemingly inexhaustible pool of gig labour.Footnote 54

The platforms had two types of contingent plans. The first involved an automatic system to increase the delivery time or to even stop taking orders, and the second was to pool the orders of several nearby stores and redistribute them according to each store's output. The latter approach was more economical, but both strategies’ success still depended on couriers, as the supervisor of L bitterly recalled:

Coffee orders usually boom between 8 and 10 am and from 1 to 4 pm. Normally, five experienced couriers, if they work hard, can handle these orders. But a courier went out to repair his electrical bike after 2 pm. In only one hour, more than 30 orders were late for the promised 30-minute delivery and the system broke down. This store had to give out 3,000 yuan in compensation to consumers.Footnote 55

Compared to the absence of one individual, collective action can cause greater damage. Similar to auto factories, where a few workers in key positions can stop production or even an entire supply chain in a just-in-time system, a courier stoppage can have a domino effect.Footnote 56 For instance, during our study, there were occasions when orders accumulated, deliveries were delayed, and consumers began to complain. The restaurant, platform and agency all pushed to clear the orders, but the chaos spiralled upwards until the system shut down.

Outsourced couriers also had informal associational power, or more precisely, a foundation of association. The store-station couriers quickly became familiar with each other and closely interacted with supervisors. The platform-based work was atomized, but the workers were not. Mutual help was normal at work. Although the platforms forbade and monitored such behaviour, it was “common practice to bring up others’ orders for the same floor in an office building” or “convenient to take others’ urgent orders along the way.”Footnote 57 During slack hours, the couriers ate at nearby fast-food places, and might chat, rest or play cards or online games together. Some young couriers lived in the same dormitory. Couriers who were from the same province or shared common interests developed even closer bonds.

Online interactions were important. For store-station couriers, the supervisors set up formal WeChat “work groups” that included three parties: supervisors, store managers and couriers. These groups were mainly for work purposes. The couriers used the groups to make daily reports about deliveries and abnormal events. Supervisors and store managers responded or offered help. The supervisors also maintained agency-only groups that included all of the couriers. The agencies’ internal information was occasionally announced in those groups. Most of the time, the couriers used the groups to chat with one another. The couriers also established their own informal groups for different purposes. Some were friendship or hobby circles; in other groups, couriers discussed unfairness at work or even the idea of mobilization. Compared to crowdsourced couriers, they effortlessly formed groups.

Management Tactics and Labour Resistance on the Ground

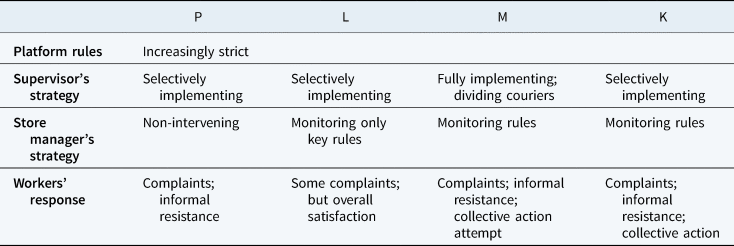

Platform labour relations are dynamic on the ground. In the four stores, the agency supervisors, together with store managers, dealt with management problems differently, and their outcomes differed (Table 1). Workers commonly complained and some informally resisted, but only those in K went on strike. While the managerial tactics and labour responses might have alleviated or aggravated tensions, the structure and power of the platforms constrained interactions.

Table 1. Comparison of the Cases

Management tactics

Changes in platform rules covered the entire delivery process, which similarly tightened in all four stores. An example was the rate at which couriers could click the “complete” buttons before their actual deliveries. In P, that rate dropped from 30 per cent in May 2019, to 20 per cent, 10 per cent and then just 5 per cent in November. In other stores, it also dropped to 5–10 per cent. Nevertheless, the “permitted” practices at each store varied.

The supervisors were crucial. Some adopted a selective implementation strategy. They recruited and retained couriers, scheduled work shifts and implemented rules that the platform had assigned to the agencies. Most of the supervisors endeavoured to stabilize the workforce because an inexperienced courier could lower delivery speed and quality, cause complaints by the store or consumers, and generate bad data that would in turn reduce the agency's performance evaluation and the supervisor's income. Thus, several supervisors tacitly exercised their discretion: rules that were regarded as overly strict and bred dissatisfaction among the couriers were downplayed, but rules that were essential to the data were always taken seriously. For instance, some supervisors decided not to fine couriers for occasionally being late. Since 2019, the platform has stipulated that if a courier cannot achieve a 90 per cent on-time delivery rate in a month, he or she “shall be punished.”Footnote 58 Supervisors in three stores, however, had never applied that rule. The supervisors did strictly follow the critical rules that implicated “hard” indicators reflected in the data and were usually pay-related. Those data impacted the sum an agency received from the platform, the salary a supervisor received from the agency and the pay rates for the couriers. The complaint rate was exemplary. For an agency,

In a month, if the complaint rate of our couriers exceeded 5 per cent – the upper threshold set by the platform – the price per order for this agency would drop from 14 yuan to 13 [yuan]; if it exceeded 10 per cent, it would further drop to 12 [yuan].Footnote 59

The consequences could be even worse: two agencies serving another platform lost their contracts because their data-based scores were low for three months.

The supervisor of M was exceptional. He enforced every platform rule literally. When the couriers complained, he tried to divide them. He appointed several “loyal” couriers as team leaders. Depending on their “loyalty,” he paid different piece rates, which led to a high turnover rate. The supervisor responded by constantly recruiting new workers. Another problem, labour oversupply, soon emerged, which sparked resistance.

The store managers also played a role, and their performance was appraised by the branded restaurants. They tended to cooperate with the agency supervisors if their interests aligned. In L store, the twin pressures of a 30-minute delivery promise and L's preparations for listing on the stock market pushed both the supervisor and store manager to maintain good data. Consequently, the couriers were fined harshly – 1.5 times an order's price – for delayed delivery. Just one consumer complaint might cost a courier a whole day's wage. However, other platform rules were pushed aside, and the store manager and supervisor actively coordinated between the food preparation staff and couriers. Thus, despite some complaints, couriers in L still found the work tolerable. However, the store manager in K insisted on a new on-time rate that the agency did not require. Store managers had more authority than supervisors, so the supervisor could not downplay this rule despite knowing about the couriers’ complaints.

Consequently, the outcomes varied. P and L stores, where the supervisors selectively implemented the rules and the store managers cooperated, were relatively peaceful. Grievances accumulated in M, whose supervisor was strict about all of the rules and tried to divide couriers, and in K, where the store manager was at odds with the agency's supervisor. Noticeably, not all rules could be flexibly implemented, as pay-affecting rules were “sensitive” for all sides. Couriers easily identified shared grievances related to those types of rules.

Collective actions

Many couriers chose to obey if “the rules were not too hard to follow” or “the fines were not too high.”Footnote 60 However, when they deemed the new rules to be “impossible” or “unbearable,” especially if their incomes were threatened, they were no longer quiet. Between peace and a strike, individualist or passive forms of resistance, such as low-key, day-to-day forms of conflict and mutual support, prevail.Footnote 61 Some couriers logged out of the system during scheduled hours and others quarrelled or fought with the supervisors or store staff. Collective actions also developed, caused by the labour oversupply in M and the price change in K.

Eventually, the organization in M failed. The supervisor's strict rule implementation led to a high turnover in staff, and his solution was to hire new couriers. On a slack day, 20 couriers waited in the store without orders. They plotted to protest. However, the supervisor's dividing tactic worked. Different groups of couriers had conflicting interests. The loyal members persuaded their friends not to join the action. The few leaders stood alone. The supervisor quickly fired them, which put a stop to any action. Afterwards, more couriers voted with their feet and left. Ironically, the oversupply problem and the supervisor's headache were both temporarily resolved.

This was not the case for K, where a strike occurred. Although the store manager's refusal to cooperate with the “pacifying” supervisor had already generated labour complaints, a new rule triggered the strike action. This rule required stricter standards and, importantly, lowered the price per order from ten yuan to nine. The platform was trying to adapt to new conditions during the Covid-19 pandemic, which shrank K's orders by 50 per cent. In 2019, the pay began to drop slowly because “the sector became more mature and the money-burning model was unsustainable.”Footnote 62 Both factors led to a reduction in the fee for the agency and, consequently, the amount distributed to each station. The supervisor announced the rule a month in advance, as wages were paid monthly.

The couriers were upset. They had already seen their incomes shrink owing to the reduction in the number of orders placed. The new rule was the final straw:

[When I heard about] the lower wages, I completely lost interest in work. They also charge fines for a violation. A customer clicked the wrong GPS location on campus, but the campus guards never allowed us to enter. It wasn't my fault! The platform did not care but fined me anyway. Fine this, fine that … So unfair!Footnote 63

At first, the couriers complained in online work groups, and several went to the supervisor, hoping he could communicate their difficulties to the agency and the restaurant. However, nothing changed. Several couriers started to talk. They came from the same province, had worked in K for more than a year and lived nearby. They spent a great deal of time together chatting. That weekend, they made a fish hotpot together and hatched a plan at the table. “We were afraid that some might leak our plan to the supervisor or the store, so we did not tell everyone.”Footnote 64

Several days later, they felt the time had come and began to mobilize others online and offline. “At that time, there were few orders, so many people were in the store. We talked about the lower pay plus limited orders and asked what we could do.” “Most of us talked with our ‘big brother’ [the supervisor], but he did not take it seriously. So, we said we should stop work.”Footnote 65 Because shifts were split between day and night, it was difficult to have everybody present, so the couriers created a WeChat group, “the rebel group,” to which they invited all the couriers. Awen, a courier from the provinces, put out an appeal to his fellow workers:

Brothers, we all know that the order price will fall next month. We have already talked to big brother but neither he nor the restaurant cared. We have no choice but “let's produce ample food and clothing with our own hands” (ziji dongshou fengyi zushi 自己动手丰衣足食).Footnote 66

This implied calling an open strike. The group then made detailed plans. At 2 pm on 22 June 2020, Awen returned to the store after delivering an order. He announced to a store staff member, “we are done,” and asked the “rebel group” to stop work and gather under an overpass bridge near K. In half an hour, 15 couriers arrived at the gathering point, including an “ace rider” who always delivered the most orders and earned the highest wages. Five couriers did not join – four were on the night shift and one remained at work. The strikers waited.

At the beginning, everyone was passionate, thinking of making big changes. As time passed, we started to worry. After an hour, we still did not see the supervisor shouting in the WeChat work group. We sent someone to the store and were told that the supervisor asked the agency to send supporting couriers from a coffee shop. We were alarmed.Footnote 67

Although they had predicted that the supervisor might do this, some began to falter in their resolve. They had planned on pressuring the management into taking back the new rule, but they still needed their jobs. They began the strike at 2 pm after the lunch hour rush so it would not cause too big an economic hit on the store: “we did not really try to make things big” but only hoped that “[the management] would raise the pay rates back.” After a while, a courier returned to work, with the false excuse that he needed to retrieve his umbrella from the restaurant. Another two followed him. Their betrayal crushed morale. Most of the strikers felt it was “over” by then and returned to the store around 5 pm. They picked up the meal containers and worked until the end of the shift.Footnote 68

Rapid resolution

The strike lasted for three hours and inflicted limited economic damage, as some orders were delayed and several customers complained. The process did not go exactly as planned. Nevertheless, the mobilization was a success. The strike raised great concerns: the regional managers of the agency and the restaurant “were furious. Among all the stores that I have managed for several years, such incidents [the strike] never happened.”Footnote 69 Managers were especially offended by the title “rebel group.”

The supervisor at K arrived ten minutes after the store manager called. Any mismanagement could jeopardize the agency's contract with the platform and hurt the image of the restaurant. He used the WeChat work group to ask what was going on, but no striker replied. Then, he called the agency to send four couriers from another store to handle orders during slack hours. This bought him time, which destroyed the couriers’ wavering solidarity.

The incident did not end there. On the night of the strike, this experienced supervisor re-scheduled work shifts and told most of the strikers to stay at home the next day. Some of the strikers expressed their regrets to him, so he called them to work and after a few days re-assigned them to L, 40 km away from K. The supervisor believed that it was not an option to fire all of the strikers, who together constituted three-quarters of the workforce. To do so would affect the store's normal deliveries and potentially trigger more confrontations. For the sake of the delivery business and the brand image, he adopted a “mild” attitude: “Neither keeping them here nor firing them all … I must shift those ‘misguided’ ones to other stores.”Footnote 70

Still, some couriers refused to concede. Not being familiar with any labour bureau or official trade union, four of them visited a street-level administration office nearby:

The next day [after the strike], we called the street office. Soon they summoned us, the supervisor and another agency manager for mediation. The next Monday, we all went there. The office staff asked us to reconcile. However, what the managers meant was that they would take us down. The staff took their side. We can't talk [because they do not listen] … The agency “boss” of our supervisor was tough. He said we must compensate them for the loss. We needed to pay and apologize to the store manager and, only if he agreed, we would be able to still work there or shift to another district. So, we thought, whatever …Footnote 71

Strikers were unhappy about the tough attitude of the agency management. The street office, lacking a specific law regarding the platforms, attempted to mediate. Disappointed with this outcome, one courier suggested arbitration, but from what they had heard in the past, arbitration procedures seemed too complicated and lengthy. Eventually, they gave up.

The strike did bring about some changes. No one was fired, in legal terms. After the failed mediation, eight couriers quit but continued to deliver as Meituan crowdsourced couriers.Footnote 72 But before that, they were put on unpaid leave for days: “[The supervisor] didn't let us work since the second day … holiday, holiday and holiday. Then, we worked for three days. Friday, Saturday and Sunday were holidays again, and so was the next week. No one else but us rested.”Footnote 73

The flexible work scheduling of the on-demand platforms became a convenient excuse for the management. The remaining workers benefited from the strike in that the supervisor did not recruit during the following month, so they earned more by taking more orders. Feeling upset but occupied with work, they fell silent. Worrying about another strike, the grassroots management constantly checked the couriers’ locations and frequently sent reminders.

The strike was kept secret. The supervisor and the store manager clamped down on all discussion of the incident and not a word about the strike or resolution was mentioned in any WeChat group. They warned all of the couriers not to tell any media or other people. Even couriers in other stores managed by the same supervisor did not know. Considering the capabilities of digitalized media today and the public's interest in platform labour problems, grassroots management was very effective in covering up the incident.

Discussion and Conclusion

The labour–capital conflict is alive and well on outsourcing platforms. The secret of frequent but invisible labour resistance lies in the platforms’ unique work regime, which this study terms “contentious despotism.” Because Chinese state policies on platforms are still evolving and trade union reform remains unsubstantial, these labour practices are neither hegemonic with effective coordinating regulationsFootnote 74 nor completely “disorganized,” as at the beginning of the market reform.Footnote 75 Still, the regime is despotic because market forces, meaning the platforms rather than the state, dominate, and although consent may exist at the grassroots, coercion prevails. Simultaneously, this regime is “contentious”: the platform arrangements are controversial and frequently spark conflict. Rather than inaction, outsourced couriers strike but have yet to make a substantial difference in their workplaces or legislation, in comparison to factory workers in frontier cases.Footnote 76

This study makes an empirical contribution by illustrating the complex labour–management dynamics on outsourcing platforms. Studies that have emphasized the legal and political aspects of the platforms have tended to overestimate their influence in practice.Footnote 77 As shown in our cases, neither the law nor policies effectively contain grievances, whether they involve labour contracts or social insurance, but the pay issues, which are the most concerning to workers, are untouched by policymaking. The lacklustre mediation at a street office, as described above, is further proof of the ineffectiveness of state interventions. Moreover, previous technology-dominated debates have underestimated or oversimplified the role of human supervision. Our cases reveal that human supervision can have complicated outcomes. It does not always alleviate tensions and may aggravate them instead. The role of human supervision is especially limited regarding pay-related rules, for which the supervisors can only pragmatically put out fires.

This study also contributes to the understanding of platform workers’ bargaining power and their actual deployment of such power. “Invisible” labour conflict is not equal to “no” conflict or “less” conflict. Outsourced couriers primarily possess workplace bargaining power and informal associational power because they are practically fixed, geographically concentrated and socially interactive, facts that other studies have underestimated. Such power is structurally stronger than that of crowdsourced couriers; compared with small factory workers, outsourced couriers are able to organize themselves much more easily thanks to the short cycles of platform businesses and their familiarity and access to instant online communications. Intriguingly, although the strikers’ workplace bargaining power was insufficient to sustain a strike that would pose a continuing challenge, the agencies could not simply fire them either. On the contrary, the fact that any strikers who left could easily become crowdsourced couriers indicates another type of structural power – marketplace alternatives enabled by the platform economy itself. Furthermore, some couriers developed a form of solidarity and understood that the root problems were vested in the platforms rather than their direct employers. Although the couriers at K complained to their supervisors, they hoped the supervisors would help to communicate their demands to the platforms.

There is a need for further research on where such strikes lead. Platforms are malleable and meant to change and this study only provides a snapshot. “Contentious despotism” is ongoing and may continue to develop. While virtual monitoring and digital intermediation are unstable and often ineffective in controlling workers, labour performance remains essential for many platforms.Footnote 78 Because the functional segmentation between operation and personnel, which was traditionally within one firm, is now extended to different organizations on the platforms, more coordination is needed. Nevertheless, the platform firms have greatly undervalued labour and, in terms of their labour management, engage in limited coordination with their agencies and other organizations. Future public policies demand more meaningful labour governance, but policy ambiguity may continue. China's long-flawed industrial relations institutions make it unlikely that the trade unions will effectively represent platform workers anytime soon. What is clear is that the current management strategies alone cannot eradicate the potential for conflict, and the frequency of labour resistance cannot be overlooked because it has nearly become an “unstable norm” on outsourcing platforms. Whether there is a shift in the platforms’ structure may depend on how large the strikes become.

Acknowledgements

This article is based upon research funded by the National Social Sciences Fund of China (Project No. 21BSH153).

Competing interests

None

Bo ZHAO is a postdoctoral fellow at the School of International Relations and Public Affairs at Fudan University in Shanghai, China. His research focuses on labour politics, including the relations between the state, market and labour, and labour processes in foreign-owned enterprises.

Siqi LUO is an associate professor of political science at the Center for Chinese Public Administration Research and the School of Government at Sun Yat-Sen University in Guangzhou, China. She is interested in many topics in industrial relations and is currently working on a project centring on new technology and labour.