Neurosurgery is a demanding surgical discipline that requires at least 6 years of residency training in Canada and, often, additional years of fellowship training. Because of the complexity of surgical procedures, there has been increasing subspecialization within neurosurgery, with subspecialty fields including open cerebrovascular, skull-base, endovascular, surgical neuro-oncology, trauma, functional neurosurgery, epilepsy, pediatric neurosurgery, complex spine, and peripheral nerve. There is a growing body of evidence suggesting that regionalization of subspecialty procedures to high-volume centres may limit patient morbidity and mortality, such as in patients undergoing clipping or endovascular coiling for ruptured and unruptured intracranial aneurysms, evacuation of intracerebral hemorrhage, carotid endarterectomy (CEA), resection of supratentorial brain tumours, resection of vestibular schwannomas, microvascular decompression for neurovascular compression syndromes, and decompression for lumbar stenosis.Reference Nuno, Patil and Lyden 1 - Reference Dasenbrock, Clarke and Witham 12 This type of regional subspecialization may have implications for neurosurgical training and the mix of operative cases to which neurosurgical residents are exposed at various training centres; however, at present, accurate neurosurgical operative case volume across Canadian neurosurgical residency programs is not known.

The Canadian Neurosurgery Research Collaborative (CNRC) is a newly formed resident-led research network involving 13 neurosurgery residency programs across Canada (www.neuronetwork.ca).Reference Dakson, Tso and Ahmed 13 The goal of the CNRC is to address fundamental neurosurgical issues by facilitating and conducting multicentre research studies that would otherwise be underpowered and less generalizable if conducted in a single-centre only. As residents become future neurosurgical attendings, it is hoped that a culture of collaboration may lead to more multicentre studies within the Canadian neurosurgical community.

In this manuscript, we describe the first study conducted by the CNRC, whose objective was primarily to assess the feasibility of such a collaborative and thus setting up the infrastructure for future multicentre clinical studies. Our second objective was to provide neurosurgical operative case volumes in a Canadian context, which may influence neurosurgery residency curriculum design.

METHODS

Resident representatives from 13 Canadian neurosurgery residency programs (93% of all Canadian training programs) agreed to participate in this study. Each residency program site lead provided, where available, administrative operative data from a 12-month period (January 1, 2014, to December 31, 2014). Administrative databases consisted of operative lists from central operating room booking or from the administration of each division of neurosurgery. If specific operative case data were not readily available, then overall case numbers in the broad categories of cranial, spine, and peripheral nerve were obtained from the administration of each division of neurosurgery. The data included procedures from adult patient hospitals. In hospitals that care for both adult and pediatric patients, the pediatric procedures were excluded. Because data were anonymized and obtained from administrative databases, formal research ethics board approval was not sought. However, the ethical principles of the Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2, 2014) were strictly upheld.

Operative cases were categorized into cranial, spine, peripheral nerve, and miscellaneous. Miscellaneous procedures included procedures that did not neatly fit into the cranial, spine, and/or peripheral nerve procedural categories such as CEA, ventriculoperitoneal shunt, baclofen pump, etc. The operative case data did not include stereotactic radiosurgery procedures, interventional neuroradiology procedures, and bedside procedures. For example, a subdural drain inserted at the bedside would not be included in the aggregated data, but would be included if the subdural drain was inserted in the operating theatre. The results included operative data from the major training hospital(s) only and not peripheral hospitals that do not have regular resident coverage.

Resident case index was defined as the ratio of number of operative cases: number of neurosurgery residents.

This index allowed a fair comparison between smaller and larger neurosurgery residency programs. The resident case index, however, is not a measure of the average operative experience per resident. Each resident representative provided his or her program’s respective neurosurgery resident number as of July 1, 2014, which included both Canadian medical and international medical graduates. Neurosurgery residents on the neurosurgical service, off-service, or on leave for research or personal reasons were included. It was not feasible to accurately determine the time spent on the neurosurgery service for each resident. For example, a resident on leave for research may only have been away for 6 months of the year or a resident may have been on leave for research but still participating in neurosurgery call several times a month. To provide some consistency within this study and for future studies, we decided to include all residents registered in the neurosurgery residency program. Fellows were not included. Although all centres provided data regarding total operative case volume, information regarding specific categories were unavailable for certain centres. The calculation of the resident case indices for these specific categories only includes centres with available data.

Descriptive data were presented using mean, median, standard deviation (SD), and range. Statistical outlier was defined as a data point that was greater than 1.5 times the interquartile range above the third quartile or less than 1.5 times the interquartile range below the first quartile. Statistics and figures were created using GraphPad Prism software (version 6.01).

RESULTS

Neurosurgery Resident Numbers

The average number of neurosurgery residents across 13 participating Canadian neurosurgery residency programs was 11 on July 1, 2014 (median, 9; range, 6-32; Figure 1).

Figure 1 Total number of residents at each participating Canadian neurosurgery residency program on July 1, 2014, including both Canadian medical graduates and international medical graduates and residents on leave for research or other reasons.

Neurosurgical Operative Case Volume

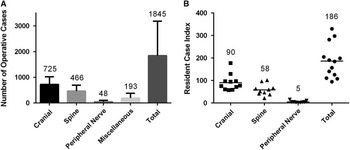

Overall, there was an average of 1845 neurosurgical operative cases performed per residency program in 2014 (n=13; median, 1647; SD, 1338; Figure 2A). The average number of cranial, spine, peripheral nerve, and miscellaneous procedures were 725 (n=11; median, 709; SD, 297), 466 (n=10; median, 400; SD, 226), 48 (n=9; median, 39; SD, 55), and 193 (n=9; median, 114; SD, 185), respectively (Figure 2A).

Figure 2 (A) Total number of operative cases per neurosurgery residency program in the broad categories of cranial (n=11), spine (n=10), peripheral nerve (n=9), miscellaneous (n=9), and total (n=13). Bar graphs represent means ± SDs. (B) Resident case indices per neurosurgery residency program in the broad categories of cranial (n=11), spine (n=10), peripheral nerve (n=9), and total (n=13). Horizontal lines represent means.

Overall, there was a mean resident case index of 186 (n=13; median, 184; SD, 76; range, 94-329; Figure 2B). One centre with a resident case index of 329 was an upper statistical outlier. The mean resident case indices for cranial, spine, and peripheral nerve procedures were 90 (n=11; median, 77; SD, 36; range, 57-177), 58 (n=10; median, 55; SD, 25; range, 21-101), and 5 (n=9; median, 4; SD, 4; range, 1-15), respectively (Figure 2B). One centre with a cranial resident case index of 177 was an upper statistical outlier and another centre with a spine resident case index of 101 was also an upper statistical outlier. Two centres with peripheral nerve resident case indices of 10 and 15 were upper statistical outliers. Each of these statistical outliers from the different categories represented unique centres.

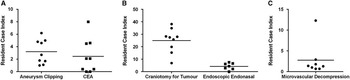

Specific Neurosurgical Operative Case Volume

The mean resident case indices for prototypical cerebrovascular procedures such as craniotomy for aneurysm clipping and CEA were 3.2 (n=9; median; 2.7; SD, 1.9; range, 1.0-6.2) and 2.5 (n=9; median, 2.1; SD, 2.7; range, 0.0-8.0), respectively (Figure 3A). There were two centres that did not perform CEA within neurosurgery. For supratentorial and infratentorial craniotomies for both benign and malignant tumours, the mean resident case index was 25.0 (n=9; median, 27.5; SD, 9.7; range, 6.9-38.2; Figure 3B). One centre with a tumour craniotomy resident case index of 6.9 was a lower statistical outlier. The mean resident case index for endoscopic endonasal procedures was 4.3 (n=7; median, 4.4; SD, 2.7; range, 0.0-7.0; Figure 3B). There was one centre that did not perform endoscopic transsphenoidal procedures. For microvascular decompression procedures, the mean resident case index was 2.8 (n=8; median, 1.4; SD, 3.9; range, 0.7-12.3; Figure 3C). One centre with a microvascular decompression resident case index of 12.3 was an upper statistical outlier.

Figure 3 Resident case indices for various neurosurgical procedure,s including (A) aneurysm clipping (n=9), CEAs (n=9), (B) craniotomy for benign or malignant brain tumours (n=9), endoscopic endonasal procedures (n=7), and (C) microvascular decompression (n=8). Horizontal lines represent means.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have presented neurosurgical operative case volumes across Canadian neurosurgery residency programs. Using the resident case index as a means to compare neurosurgery residency programs, there was variability in operative opportunity among the different programs, especially in subspecialty procedures. A key strength of this study is that the results were based on concrete administrative data and not on estimates. These results could therefore be used to facilitate neurosurgery residency curriculum development.

An interesting finding from this study involved the unique identities of “outlier” centres; that is, the upper statistical outliers in resident case indices for microvascular decompression, cranial procedures, spine procedures, peripheral nerve procedures, and overall neurosurgical procedures were all different neurosurgery residency programs. This result indicates that certain residency programs have unique strengths that may differentiate them from other programs.

This study also found that certain procedures, such as CEA and endoscopic transsphenoidal procedures, were not performed at some neurosurgery residency programs. Although competency in endoscopic transsphenoidal procedures may be designated as a fellowship-level task, competency in CEA is explicitly listed in the Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) objectives of training for the specialty of neurosurgery under “exposure of extracranial carotid arteries, and simple arterial repair.” 14 In reality, the type of surgeon who performs CEA largely depends on established local practice patterns and can include neurosurgeons, vascular surgeons, cardiac surgeons, or a combination of these. Presumably, residency programs that do not perform CEA within neurosurgery are sending residents to off-service rotations in vascular surgery or cardiac surgery to gain this experience, in accordance with RCPSC accreditation standards. Such off-service operative procedures were not captured in our results. A broader philosophical question is whether specific procedures that are not performed in all centres should be considered necessary competencies within neurosurgery.

Currently, the RCPSC has not set operative volume standards for specific procedures, although there are ongoing developments to transition to a competence-by-design curriculum. 15 The Residency Review Committee for Neurological Surgery of the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education has set operative volume minimums for US neurological surgery residency programs, with some programs sending residents to outside institutions to meet these requirements, although the educational basis for this decision remains sparse.Reference Gephart, Derstine and Oyesiku 16 Nevertheless, in the United States, one can see substantial difference in resident operative exposure between residency programs. On the basis of Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education case log data, there was a 4-fold difference between the bottom 10% and the top 10% of residency programs in annual mean number of operative spine procedures (166 vs 665).Reference Daniels, Ames and Smith 17 Reulen and Marz have suggested, somewhat arbitrarily, a resident case index of 250 to 300 operations per year at their specific neurosurgery residency program in Germany.Reference Reulen and Marz 18 However, it is unclear what the minimum operative experience required is to properly train residents to become competent neurosurgeons. Minimum operative case experience for competency is likely trainee-specific. 15

Case volumes for Canadian neurosurgery postgraduate year 1 residents over the first 3 months of neurosurgery have been studied before from online surveys.Reference Fallah, Ebrahim and Haji 19 Surgical training camps may allow junior neurosurgery residents to have a smoother transition from medical school to residency.Reference Haji, Clarke and Matte 20 Simulators in neurosurgical training continue to be developed and refined and may become an integral part of many residency programs, especially in areas with lower surgical exposure.Reference Kirkman, Ahmed and Albert 21 - Reference Lau, Denning and Lownie 23 These simulators may help to identify future neurosurgical trainees although longitudinal studies need to be performed.Reference Winkler-Schwartz, Bajunaid and Mullah 24

It is worth noting that this study has some significant limitations. First, although every centre provided data regarding resident numbers and total neurosurgery operative case volume, not every centre was represented in the specific surgical categories. Another limitation is that the accuracy of the results is dependent on the accuracy of the coding within administrative databases. Third, inconsistency is introduced because certain procedures can be performed either at the bedside or in the operating theatre; accordingly, some procedures would be excluded from administrative databases if performed at the bedside, including insertion of external ventricular and subdural drains. Fourth, the overall operative results could fluctuate from year to year; hence, our study results represent merely a snapshot. Also, stereotactic radiosurgery and interventional neuroradiology procedures were excluded in our results, although they are important in the management of neurosurgical patients. Finally, the operative data were taken from the 2014 calendar year, but the neurosurgery resident number was accurate as of July 1, 2014, the mid-point of the operative data timing. Thus, it is possible that resident numbers could have fluctuated slightly in the 6 months before July 1, 2014.

As mentioned in the Methods section, the resident case index is not an indication of the average operative experience per resident. In fact, the resident case index is likely an underestimate of the actual resident operative experience: given that at times there may have been more than one resident actively participating in many procedures, not all residents were on the neurosurgical service at all times during the 2014 calendar year, and some procedures performed outside the operative theatre were not included (e.g. external ventricular drain insertion). We also acknowledge the potentially sensitive nature of declaring operative case volumes from different centres. Thus, absolute case numbers from each centre were not presented (including range) and individual centres cannot be easily identified from the results presented. Future studies may address actual resident operative experience using case logs, analyzed by postgraduate year level.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, the CNRC has presented neurosurgical operative data from 13 neurosurgery residency programs across Canada. In doing so, we have successfully completed a multicentre study led by a nationwide network of neurosurgery residents, which bodes well for future collaborative studies. There was some variation in resident operative opportunity, especially in certain neurosurgical procedures, which may be reflective of subspecialization in specific centres. These data may be useful as RCPSC neurosurgery residency training transitions to a competence-by-design curriculum.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors acknowledge the administrative support provided by Ryojo Akagami (University of British Columbia), Sandy Strandberg (University of British Columbia), Monica Lafrance (University of Alberta), B. Matt Wheatley (University of Alberta), John Wong (University of Calgary), Michael Kelly (University of Saskatchewan), Carissa Kenaschuk (University of Saskatchewan), Amrit Deol (University of Saskatchewan), Jocelyne Dufresne (University of Manitoba), Linda Gould (Hamilton Health Sciences), Erin Kelleher (Hamilton Health Sciences), Joseph Tam (University of Toronto), Richard Moulton (University of Ottawa), Jeffrey Atkinson (McGill University), Kevin Petrecca (McGill University), Luisa Birri (McGill University), David Fortin (Université de Sherbrooke), Mona Bouchard (Université Laval), and Lorraine Smith (Dalhousie University).

Disclosures

Results were presented as a platform presentation at the Canadian Neurosurgical Society Chair’s Select Abstracts session at the Canadian Federation of Neurological Sciences Annual Congress in Montreal, QC, on June 22, 2016.

The authors report no relevant conflict of interest.

Statement of Authorship

This study was made possible by the joint efforts of the Canadian Neurosurgery Research Collaborative steering committee members. All authors provided administrative data. MT and AD performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript and approved the final version.