A 58-year-old man with no relevant history presented with a right hemianopsia. Five hours before his admission, he developed flashing and shimmering lights in the right visual fields. Initial computed tomography (CT) revealed an area of hypodensity in the left occipital lobe in the distribution of the posterior cerebral artery (Figure 1). Besides the hemianopsia, the neurological examination was unremarkable. The clinic-radiological picture was suggestive of a stroke and he was admitted for additional investigations and management. CT angiography revealed no vessel occlusions and a perfusion CT revealed mild hyperperfusion in the affected region. Given the acuity of presentation, this was interpreted as ischemic stroke with spontaneous recanalization and compensatory hyperperfusion. During his first 24 h within hospital, he experienced a generalized tonic-clonic seizure and subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a confluent hyperintensity in the left temporo-occipital region with a small area of restricted diffusion and no enhancement (Figure 1).

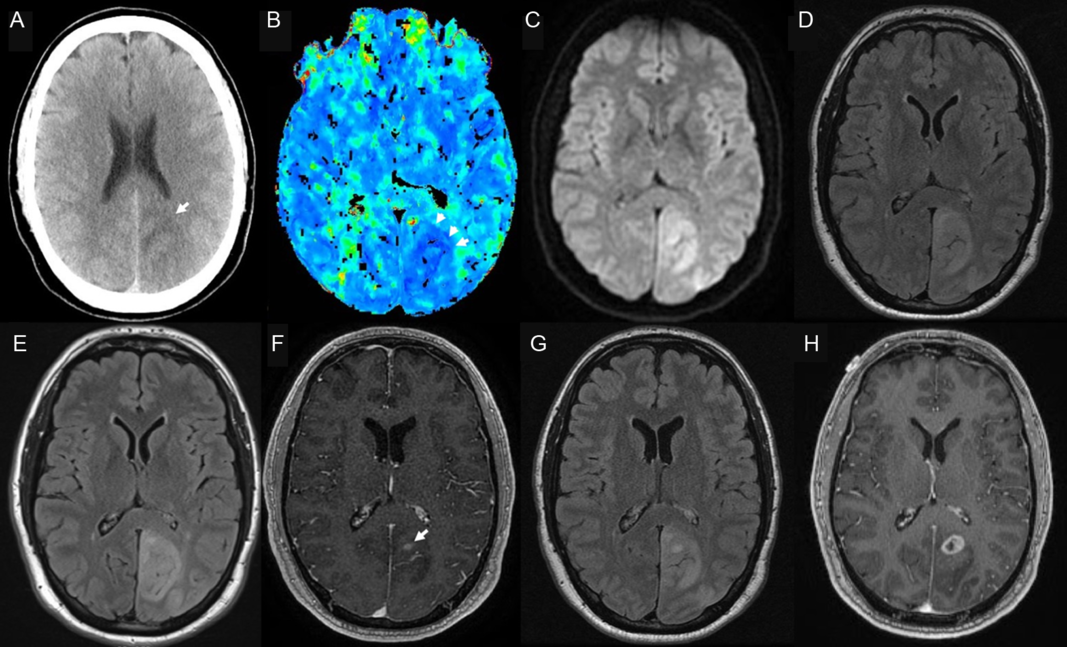

Figure 1: CT on day 1 showed an ill-defined hypodensity in the left posterior cerebral artery territory (A, arrow). A perfusion CT revealed an area of hyperperfusion on Tmax in the same territory (B, arrowheads), as well as an increase in blood flow (not shown). An MRI done on the next day showed diffusion restriction (C) and a T2 fluid attenuation inversion recovery hyperintensity (D) in the left occipito-parietal lobe, and no enhancement (not shown). A repeat MRI on day 7 revealed an unchanged area of T2 hyperintensity (E), but also patchy foci of gadolinium enhancement (F, arrow). A repeat MRI a week later was unchanged (G), but 1 month later, a ring-enhancing lesion with perilesional edema was evidenced by a new MRI (H).

The unusual presentation prompted further work-up. In particular, photopsias are an infrequent symptom of stroke involving the occipital lobe.Reference Baier, de Haan and Mueller1 An electroencephalogram showed focal slowing in the left occipital lobe but no epileptic discharges, and cerebrospinal fluid was bland and negative for an infectious etiology. Autoimmune/paraneoplastic encephalopathy panels and a chest–abdomen–thoracic CT were negative. After 7 days, there were no new symptoms and the visual field defect remained stable. A new MRI revealed an unchanged area of T2 hyperintensity, but also a subtle, patchy area of enhancement (Figure 1). Given the clinical stability and negative work-up, the patient was discharged with plans to follow up with new MRI and a CT/positron emission tomography scan. Unfortunately, 10 days later, the patient presented to the emergency room with a breakthrough seizure, but unchanged radiographic findings (Figure 1). His anti-seizure medication was optimized, but a month later, the patient returned after developing new positive visual phenomena. An MRI revealed a ring-enhancing lesion in the left occipital lobe with perilesional edema suggestive of a glial tumor (Figure 1). A biopsy confirmed a high-grade glioma.

The typical presentation of glioblastoma is a rapidly progressive neurological deficit, but acute presentations due to seizures or hemorrhage are well known.Reference Omuro and DeAngelis2 Ischemic strokes associated with glioblastoma are rare, but infiltration or compression of arterial walls, leptomeningeal involvement, and a procoagulant state have been described as possible precipitant factors.Reference Lasocki and Gaillard3 De novo glioblastomas have also been reported in the area previously affected by a stroke, possibly due to loss of blood–brain barrier integrity, immune surveillance or changes in the lesion microenvironment.Reference Ferenczi, Saadi, Bhattacharyya and Berkowitz4 Gliomas mimicking ischemic stroke have been reported in the literature, with glioblastomas and high-grade gliomas being the most common.Reference Morgenstern and Frankowski5-Reference Li, Li and Hu7 Seizures are one of the most frequent presenting symptoms in glioblastoma, occurring in up to 40% of cases, but seizures also account for approximately 20% of all suspected strokes and are the most common stroke mimic.Reference Omuro and DeAngelis2,Reference Brigo and Lattanzi8 The occipital lobe is the least frequent lobar localization for gliomas, although it is also a highly epileptogenic area.Reference Larjavaara, Mäntylä and Salminen9,Reference Cayuela, Simó and Majós10 Diagnostic certainty is essential in order to expedite tissue diagnosis and treatment. In our case, the radiological presentation coupled with the eloquent localization made it difficult to justify an early biopsy, and radiographic follow-up proved essential for subsequent diagnosis.

Disclosures

CRCL received personal fees from consultancy in the care of the patient. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Statement of Authorship

AF and KT gathered the clinical information, performed chart review, and revised the manuscript. FL provided images and edited the content of the manuscript. CRCL wrote the manuscript and approved the final version.