1. Introduction

In natural languages, there are morphemes that are semantically underspecified; typical examples are those which are traditionally called pronouns, such as personal pronouns, I, you, they, it, she, and he in the English language and their exact or quasi-counterparts in other languages. These pronouns obtain semantic content from the context either inside or outside the utterance in which they appear. There are also some morphemes that only obtain semantic content from within the utterance in which they appear. A typical example is the expletive it in English. See the following examples (Cann et al. Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005, 194).Footnote 1

(1)

a. That we are wrong is possible (but not likely).

b. It's possible that we are wrong (but it's not likely).

The expletive pronoun it in (1b) obtains its content from a later string that we are wrong. In this sense, it in (1b) is just a placeholder.

Morphemes that function as placeholders are not restricted to pronouns; for example, the copular verb be in English has been analyzed as a placeholder in Cann et al. (Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005), which successfully accounts for the various uses of be. In the following sentences, be (in its various inflectional forms), contributes a placeholder the content of which is provided by some expressions that come up later. The semantic placeholder of be in (2a)-(2c) is filled in respectively with the semantic content of happy, on the train, and a teacher.

(2)

a. John is happy.

b. Robert was on a train.

c. Mary is a teacher.

It follows that copular verbs in any languages are all placeholders. For example, the copular verb shi in Mandarin Chinese has been analyzed as contributing a placeholder (Wu Reference Wu2011; Li Reference Li2016). This paper, by looking into the clitic morpheme de in the so-called fake modification constructions in Mandarin Chinese, continues the enterprise of investigating lexical semantic underspecification. (See the work mentioned above.) The grammatical property of this morpheme has been a controversial topic in Chinese linguistics but its semantic contribution has been little considered. The existing analyses, which are all implemented in the framework of Generative Grammar, suffer from the problem of theoretical incoherence. In this paper, a theoretical account of fake modification constructions is formulated in the framework of Dynamic Syntax (Kempson et al. Reference Kempson, Meyer-Viol and Gabbay2001; Cann et al. Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005). I argue that different fake modification constructions involve different de-morphemes. The different de morphemes, while having different syntactic distributions, all contribute a predicate that does not have its own meaning but obtains semantic content from context. This analysis of de provides a partially unitary characterization of the four fake modification constructions. The rest of the paper unfolds as follows. In section 2, basic data of the so-called canonical use of de and the puzzling use of de are described. In section 3, four existing accounts of fake modification constructions are reviewed. In section 4, it is argued that de can function as a two-place predicate although in a rather restricted way and that its presence is restricted by what precedes it and imposes requirements on what follows it. In section 5, a formal characterization of fake modification constructions is formulated in the framework of Dynamic Syntax. section 6 is the conclusion of the paper.

2. Basic Data

In this section, fake modification constructions involving de between two noun phrases are described. These constructions are puzzling in that the use of de in them is quirky compared with its use in typical modification constructions. In order to make clear why the use of de in fake modification constructions is puzzling, the typical use of de in modification constructions is briefly described first.

2.1 The use of de in modification constructions

In Mandarin Chinese, the monosyllabic morpheme de (zero tone) occurs in a modifier phrase, as shown in (3).

(3)

a. Měilì de fēngjǐng xīyǐn dàliàng yóurén.

beautiful de scenery attract a.large.number.of tourist

‘The beautiful scenery attracts a large number of tourists.’

b. Wǒ de fùqīn shì gōngchéngshī.

1st.sg de father be engineer

‘My father is an engineer.’

c. Zhèi-běn shū shì wǒ de.

this-cl book be 1st.sg de

‘This book is mine.’

d. Zhèi-běn shù shì wǒ de shū.

this-cl book be 1st.sg de book

‘This book is my book.’

In (3a), de is cliticized to the word měilì ‘beautiful’ and the phrase měilì de ‘beautiful de’ modifies fēngjǐng ‘scenery’. In (3b), the possessive modifier, wǒ de, which consists of the first person singular pronoun wǒ ‘1st.sg’ and de, is semantically identical to the possessive pronoun ‘my’ in English. In (3c), wǒ and de jointly work as mine in English does. But it can be argued that in (3c), wǒ de is the same as that in (3b); the evidence is that a noun can be added after wǒ de in (3c), shown in (3d).

Since the de-phrase modifies a nominal head, de is usually treated as a nominal modification marker. A noun phrase in which de functions as a modification marker, undoubtedly, can be anaphorically referred to by a pronoun, as shown in (4). In (4a), tā ‘3rd.sg’ refers to měilì de fēngjǐng ‘beautiful de scenery’ [the beautiful scenery]; in (4b), tā ‘3rd.sg’ refers to wǒ de fùqīn ‘1st.sg de father’ [my father].

(4)

a. Měilì de fēngjǐng xīyǐn dàliàng yóurén, dāngdì rén

beautiful de scenery attract a.large.number.of tourist, local people

quán kào tā móushēng.

all rely.on 3rd.sg make.a.living

‘The beautiful scenery attracts a large number of tourists and the local people all rely on it to make a living.’

b. Wǒ de fùqīn shì gōngchéngshī, dànshì tā bù dǒngdé

1st.sg de father be engineer, but 3rd.sg neg know

zěnme jiàoyù háizǐ.

how educate child

‘My father is an engineer, but he does not know how to educate a child.’

However, there is evidence that even though de in (3a)/(4a) and (3b)/(4b) has long been taken to be a modification marker, the syntactic relationship between de and an expression to which it is cliticized varies from case to case. Compare the following two sentences first to see the variation.

(5)

a. Měilì de fēngjǐng xīyǐn rén; *(měilì de) rén gèng xīyǐn

beautiful de scenery attract people; beautiful de people more attract

rén.

people

‘Beautiful scenery attracts people; (beautiful) people more attract people.’

b. Tā de fùqīn shì gōngchéngshī, (tā de) mŭqīn shì dàxué

3rd.sg de father be engineer, 3rd.sg de mother be college

jiàoshī.

teacher

‘His father is an engineer and his mother, a college teacher.’

In (5a), měilì de ‘beautiful de’ in the second clause cannot be omitted unless the meaning of the modifier is lost; in contrast, in (5b), tā de ‘1st.sg de’ can be omitted without losing the meaning of the modifier.

Semantically, while de in the case of adjectival modification seems to contribute little meaning,Footnote 2 in the case of a genitive modification such as (3b)/(4b)/(5b), de contributes the meaning of possession. As can be seen in (6), where the absence of de results in the loss of the meaning of possession.

(6)

a. Yìfū túshūguǎn

Yifu library

‘The Yifu Library’

b. Yìfū de túshūguǎn

Yifu de library

‘Yifu's library’

In (6a), de does not appear and the phrase does not have the meaning of possession; the modifier is interpreted as a personal name after which a building is named. In (6b), de appears and the noun preceding de is interpreted as the possessor of a building. Another example that shows the semantic contribution of de between two nouns in a possessive relationship is given below.

(7) Zhèi zhǒng píngguǒ zhī’er shì jiǎde, lǐmiàn bù hán píngguǒ de zhī’er

this kind apple juice be fake, inside neg contain apple de juice.

‘This kind of apple juice is fake, for it does not contain any juice of apples.’

In (7) píngguǒ zhī’er ‘apple juice’ is semantically distinguished from píngguǒ de zhī’er ‘juice of apples’; in the former, píngguǒ ‘apple’ does not necessarily mean the fruit from which some juice is extracted; it may simply refer to some taste similar to that of an apple, while píngguǒ de zhī’er unambiguously expresses the natural possessive relationship between the fruit and its juice. Treating de as semantically void is at most a technical simplification because the presence and absence of de, as shown in (6), makes a difference in meaning. Even if de does not contribute a conceptual meaning on its own, it must have the function of triggering some inference that leads to the semantic effect observed in cases like (6).

To sum up, occurring in different types of modification constructions, de makes different contributions. In this sense, de is either a polysemous morpheme or different morphemes. In the following section, I show that de can occur between two expressions that do not have the relationship of modification, which, as is shown in section 3, has been treated as a genitive morpheme in some existing accounts.Footnote 3

2.2 The use of de in four fake modification constructions

Of those non-modification uses of de, one is superficially related to the possessive/genitive de. In this use, de occurs between two nominal phrases between which, however, there is no relation of possession, as illustrated by the underlined parts in the sentences in (8).

(8)

a. Zhāngsān de lánqiú dǎ dé hǎo.

Zhangsan de basketball play prt good

‘Zhangsan plays basketball well.’

b. Zhāngsān pǎo-le sān fēnzhōng de bù.

Zhangsan run-asp three minute de step

‘Zhangsan ran for three minutes.’

c. Zhāngsān dǎ Zhāngsān de lánqiú (Lǐsì pǎo Lǐsì de bù).

Zhangsan play Zhangsan de basketball Lisi run Lisi de step.

‘Zhangsan plays basketball; (Lisi runs) [Note: the two-clause sentence has the implicature that the two persons do/did not interfere with each other].’

d. Zhèi dùn fàn, Zhāngsān de dōngjiā.

this cl meal Zhangsan de host

‘As for the meal, Zhangsan is the host.’

The fact that de appears between two nominal expressions results in the impression that it is a modification marker, like that in (3a), (3b), (3d), (4a), (4b), (5a), (5b), and (6b). However, as was indicated above, there is no possessive relation between the two nouns in all the four sentences in (8).

In (8a), Zhāngsān is not understood as the owner of lánqiú ‘basketball’, which in the sentence does not express an entity or a kind of entity but rather a kind of game. If Zhāngsān de lánqiú is interpreted as a composite concept that involves a possessive relationship, the sentence as a whole is nonsensical.Footnote 4 In (8b), sān fēnzhōng de bù ‘three minute de step’ can hardly be interpreted without an appropriate context; therefore, there cannot be a relation of modification between sān fēnzhōng and bù. In (8c), like in (8a), Zhāngsān de lánqiú ‘Zhangsan de basketball’ does not express a possessive relationship between Zhāngsān and lánqiú. The whole sentence, including the part in the brackets, expresses a distinction and separation of what Zhāngsān does/did and what Lǐsì does/did, having a conventional implicature that Zhāngsān and Lǐsì do not interfere with each other. In (8d), Zhāngsān de dōngjiā ‘Zhangsan de host’ does not involve a genitive relationship; instead, it expresses a subject-predicate relationship, in which Zhāngsān is assigned the status of a host.

Among the four constructions, (8b) looks slightly different from the other three. In (8b), what occurs before de is the temporal expression sān fēnzhōng ‘three minute’. In the other three, what occurs before de is a personal noun. However, there is evidence that the personal noun Zhāngsān, which occupies the initial position in (8b), can occur immediately before de, as is shown in (9), which is semantically equivalent to (8b). It should be noted that (9) looks exactly the same as (8a) regarding the linear order of the NPs flanking de.

(9) Zhāngsān de bù pǎo-le sān fēnzhōng.

Zhangsan de step run-asp three minuite

‘Zhangsan ran for three minutes.’

The constructions illustrated by the sentences in (8) are dubbed as fake modification constructions (e.g., Zhu Reference Zhu1982, and works to be reviewed below), because in these sentences, de and the noun phrase that precedes it together have the appearance of constituting a modifier of the noun phrase that follows de, even though there is no recognizable relation of modification between the two expressions that respectively precede and follow de.

3. Existing analyses of fake modification constructions

Theoretical linguists have long been interested in fake modification constructions. Many accounts have been proposed to characterize the syntactic and semantic properties of de. Below is a review of four existing accounts, which take three different approaches in the framework of Generative Grammar. Other analyses that can be found in the literature (Tang Reference Tang2010; Guo Reference Guo2017; Pan and Lu Reference Pan and Lu2011) are also carried out in the same framework and adopt similar assumptions. This review mainly aims to demonstrate the problems that existing analyses of de in these constructions suffer from. Generally, there are three approaches to the appearance of de in fake modification constructions. One is to assume that de is inserted for a syntactic purpose. The second is to assume that de is a genitive morpheme, functioning like ‘'s’ in English. The third is to assume that de is inserted to satisfy some phonological-syntactic interface mapping rule. The three approaches are reviewed one by one.

3.1 The syntactic insertion approach

Mei (Reference Mei1978) first proposes a generative account of the generation of a fake modification construction, with (10a) as an example and (10b) as a reference for facilitating discussion.

(10)

a. Tā de lǎoshī dāng dé hǎo.

3rd.sg de teacher do prt good

‘He served well as a teacher.’

b. Tā dāng lǎoshī dāng dé hǎo.

3rd.sg do teacher do prt good

‘He served well as a teacher.’

Based on the fact that (10a) and (10b) are the same semantically, Mei proposes the following operations of generating (10a). It is assumed that (10a) has the deep structure given in (11a), which looks identical to (10b). Then, the first token of the verb dāng ‘act.as’ is deleted, shown in (11b). Next, de is inserted where dāng ‘act.as’ has been deleted, shown in (11c).

(11)

a. Tā dāng lǎoshī dǎng dé hǎo. (deep structure)

3rd.sg act.as teacher act.as prt good

b. Tā dāng lǎoshī dāng dé hǎo. (deleting the first verb ‘dāng’)

3rd.sg act.as teacher act.as prt good

c. Tā de lǎoshī dāng dé hǎo. (inserting ‘de’).

3rd.sg de teacher act.as prt good

This account suffers from three defects. First, it is not clear what motivates the deletion of dāng in (11a). Second, it is not clear whether this deletion is merely a phonetic deletion in the surface structure or a lexical deletion in the deep structure. Third, whatever the essence of the deletion of dāng is, an account of the syntactic and semantic properties of de is wanting; that is, there should be an explanation of why de can be inserted into a position where a verb has been deleted.

Briefly, the account seems to be nothing but an ad hoc manipulation to yield the syntactic form of (10a) because the deletion and insertion operations are not well motivated in theory and nothing is said about the syntactic and semantic properties of de that endow the morpheme with the qualification for being inserted in a position where a verb can occur. In spite of these defects, this account is enlightening in that the suggestion that de can be ‘inserted’ in a position where a verb can occur implies that it is very likely that de in this case is close in function to a verb. A novel account proposed below capitalizes on this implication.

Huang (Reference Huang1982, Reference Huang1998) proposes a different and rather sophisticated account of the same fake modification construction, where it is also assumed that de is inserted for some syntactic purpose. The operations assumed in this account are sequentially displayed in (12).

(12)

a. Tā dāng lǎoshī dé hǎo (deep structure)

3rd.sg act.as teacher prt good

b. Tā lǎoshī dāng dé hǎo (‘lǎoshī’ is fronted)

3rd.sg teacher act.as prt good

c. Tā de lǎoshī dāng dé hǎo (‘de’ is inserted)

3rd.sg de teacher act.as prt good

As shown in (12a), a deep structure is assumed, where the morpheme at issue de does not appear, and then lǎoshī ‘teacher’ is fronted to a position next to tā ‘3rd.sg’, as shown in (12b). To account for de's insertion, Huang (Reference Huang1982, Reference Huang1998) assumes that the linear adjacency of tā and lǎoshī leads to a structural reanalysis or restructuring, giving rise to a NP which licenses the insertion of de. The computation of reanalysis is schematically represented as (13).

(13) NP 1 NP 2 → [NP NP 1 NP 2] → [NPNP 1 de NP 2]

This account is problematic in the following aspects: First, the second step, shown in (12b), is poorly motivated. It is not known why lǎoshī is fronted to a preceding position instead of remaining in situ. Second, it is not clear in which sense reanalysis is applied as a mechanism in generating the structure at issue. If structural reanalysis is adopted in the sense of Manzini (Reference Manzini1983) and others of the same line of thought, it is mysterious why de is inserted between two nominal phrases which otherwise have a loose structure relationship and get structurally closer to each other through reanalysis. As was illustrated by (6) and (7), the presence and absence of de between two nominal phrases produce different semantic effects. Thus, simply assuming that de is inserted between two NPs that have a closer structural relationship because of undergoing reanalysis is not enough in face of the semantic facts. Third, even if the structural relationship between the two adjacent NPs is reanalyzed as an NP, the structural position for de to be inserted into is still unavailable because [NP NP 1 NP 2] is a structure that has already been formed through applying some phrase structure rule(s). Therefore, the insertion of de is poorly motivated. Fourth, if NP 1 and de constitute an NP, called NP 3, then the phrase structure on the rightmost of (13) should be [NP [NP NP 1 de] NP 2] rather than [NP NP 1 de NP 2].

3.2 The genitive approach

Huang (Reference Huang2008) proposes another account, which is intended to solve the problem of overgeneration that the previous account (Huang Reference Huang1982, Reference Huang1998) suffers from and avoid using reanalysis as a theoretical apparatus because of its being poorly motivated. The theory of lexical decomposition and the theory of head movement are adopted to explain the generation of fake modification constructions. Regardless of the problem of overgeneration, the new account, theoretically, does not fare better than the one reviewed above, for it suffers from the problem of theoretical incoherence, which can be seen in his account of the generation of the following two sentences. The first one is (14), which is another instance of the construction instantiated by (8c).

(14) Nǐ jiāo nī de yīngwén.

2nd.sg teach you de English

‘You teach English [as your own business].’

The generation of the surface structure of (14) is shown as Figure 1. In the deep structure, where DO stands for a light verb, nǐ de ‘2nd.sg de’ as a phrase occupies the Specifier (Spec) of a Gerund Phrase (GP) headed by a gerund (G), on which there is an empty category. Put in plain English, nǐ de jiāo yīngwén ‘2nd.sg de teacher English’ is treated as a gerund phrase in which ni de ‘2nd.sg de’ is a genitive modifier of jiāo yīng ‘teach English’. The verb jiāo, which initially occurs in a low position, moves upward via G(erund) to a higher position occupied by the light verb DO. This account faces an obvious empirical challenge: nǐ de jiāo yīngwén is in no way a well-formed phrase. Although undeniably, in Chinese a phrase like tā de dàolāi ‘3rd.sg de arrive’ [his arriving/arrival] is intuitively acceptable, a phrase like tā de dào Běijīng ‘3rd.sg de arrive Beijing’ is absolutely bad. Even if there is such a thing as a gerund, there is no telling evidence that a transitive verb and its object complement can appear in a gerund phrase.

Figure 1: Generation of the surface structure of example (14)

The second one is (10a), repeated as (15), which is structurally the same as (8a). According to Huang (Reference Huang2008), the sentence is generated through the syntactic computations shown in (16).

(15) Tā de lǎoshī dāng dé hǎo.

3rd.sg de teacher act.as prt good

‘He teaches well.’ [Literally: He acts as a teacher well.]

(16)

a. Step 1: tā DO tā de dāng lǎoshī (dé hǎo). (deep structure)

b. Step 2: tā dāngi tā de ti lǎoshī (dé hǎo) (the movement of the core verb dāng)

c. Step 3: [e] dāngi tā de ti lǎoshī (dé hǎo). (the deletion of the subject tā)

d. Step 4: [tā de t lǎoshī ]j dāng tj (dé háo). (the fronting of the object tā de lǎoshī to become an accusative subject)

e. tā de lǎoshī dāng (dé hǎo) (Step 5: the surface structure)

As shown in (16a), the deep structure consisting of a light verb DO, its subject and object complements are generated. The verb dāng in the gerund phrase moves (via the assumed empty category on the head of the gerund phrase) to where DO is located, shown in (16b). Then the subject of the deleted DO is deleted. Subsequently, tā de ti dāng lǎoshī moves to where tǎ has been deleted, resulting in (16e).

This account suffers from the following problems:

First, Huang (Reference Huang2008) is silent on the structural relationship between dé hǎo and tā de dāng lǎoshī in (15). It is not clear whether dé hǎo is part of the gerund phrase that includes tā de dāng lǎoshī. If it is, why can't dé hǎo move together with tā de dāng lǎoshī to the subject position, resulting in tā de lǎoshī dé hǎo dāng, which is unacceptable? What is worse is that without dé háo, (15) remains unacceptable. Although dé hǎo is so important for the well-formedness of (15), the generative account simply leaves it aside as something trivial. Apparently, this account fails to achieve descriptive adequacy (Chomsky Reference Chomsky2014).

Second, although the movement of the gerund phrase to the subject position is motivated by the need for an explicit subject, the reason the original subject is deleted is not clearly stated. It seems that the deletion of the NP and the movement of a gerund phrase to the position of the NP is nothing but an ad hoc stipulation aimed to construct the surface structure.

Third, in (16d), tā de t lǎoshī occurs in the subject position as a result of movement; this leads to the fact that the trace that the movement of dāng leaves behind in Step 2 is higher than the position of dāng. The consequence of this operation is that the trace of dāng is neither antecedent-governed nor theta-governed by dāng ‘act.as’, which violates ECP, a principle that cannot be violated in the framework in which Huang's formulates his account.

Fourth, the gerund phrase assumption is short of empirical corroboration; tā de dāng lǎoshī, just like tā de jiāo yīngwén, is in no way a well-formed phrase in Chinese. Other generative accounts (Tang Reference Tang2010; Guo Reference Guo2017; Pan and Lu Reference Pan and Lu2011), which will not be reviewed in detail, either assume that de is the marker of a genitive modifier subsumed in a gerund phrase as Huang (Reference Huang2008) does or assume that de is inserted between two adjacent NPs which undergo reanalysis, constituting a larger NP as Huang (Reference Huang1982, Reference Huang1998) assumes. For these reasons, they suffer from the same problem of making assumptions that go against empirical facts.

3.3 The phonological-syntactic interface approach

Zhuang (Reference Zhuang2017) proposes an account of fake modification constructions instantiated by (10a), where the insertion of de is phonologically motivated. As Zhuang (Reference Zhuang2017) argues, tā and lǎoshī belong to the same prosodic domain if the sentence is pronounced at a fast speed although they belong to different syntactic components and do not semantically combine. This results in a mismatch between the prosodic structure and the syntactic structure of the sentence, violating the phonological-syntactic Mapping Rule (Tokizaki Reference Tokizaki, Tamanji, Hirotani and Hall1999, Reference Tokizaki2005, Reference Tokizaki2007). By the insertion of a pause, or ya or ba or de between tā and lǎoshī, the mismatch can be solved because morphemes such as ya, ba and de are clitics that are attached to the preceding content phrase.

This analysis is faced with empirical challenges. Consider the examples in (17). Intuitively, when ya or ba is inserted between tā and lánqiú, a pause can still be inserted, immediately following ya or ba, for example in (17a). In contrast, when de is inserted between tā and lánqiú, further inserting a pause results in awkwardness, such as (17b). If de is inserted merely to construct the correspondence between the prosodic and syntactic structures, it is surprising that a pause cannot follow it. To my knowledge, a pause cannot occur between a verb and its object in natural Chinese speech; this fact makes de at issue look rather similar to a verb. This similarity is further elaborated in section 4.

(17)

a. Zhāngsān ya/ba [ ] lánqiú dǎ dé hǎo.

Zhangsan ya/ba pause basketball play prt well

‘As for Zhangsan, he plays basketball well.’

b. *Zhāngsān de [ ] lánqiú dǎ dé hǎo.

Zhangsan de pause basketball play prt well

‘As for Zhangsan, he plays basketball well.’

Another fact that suggests that Zhuang's (Reference Zhuang2017) account is problematic is given below.

(18)

a. Lánqiú ya/ba/[ ] Zhāngsān dǎ dé hǎo.

basketball ya/ba/pause Zhangsan play prt well

‘As for basketball, he plays it well.’

b. *Lánqiú de Zhāngsān dǎ dé hǎo.

basketball de Zhangsan play prt well

‘As for basketball, he plays it well.’

In (18a), lánqiú ‘basketball’ appears in sentence-initial position, as a topic; the sentence is fully acceptable no matter whether ya, ba, or a pause follows the topic or not. Syntactically, the topic, lánqiú and the subject Zhāngsān do not belong to the same syntactic components and do not semantically combine, inserting ya, ba, or a pause after the topic is not surprising according to Zhuang (Reference Zhuang2017). However, as shown in (18b), inserting de after the topic is disallowed. This fact supports my argument that Zhuang's (Reference Zhuang2017) account is not on the right track. Besides, although (18b) is unacceptable for the given translation therein, the sentence is acceptable when it has the pragmatically odd meaning ‘The basketball plays Zhangsan well’. This fact strongly suggests that the presence of de in this fake modification construction is not motivated at the phonological-syntactical interface but rather at the semantic-syntactic interface.

4. New Observation Of de

The difficulties that the existing accounts are faced with justify further investigation and an alternative analysis of de. By drawing upon the literature and new observation, I argue that de contributes a semantically underspecified predicate, the meaning of which is specified via context-based inference.

4.1 De as a semantically underspecified predicate

It has been observed that de in some uses occupies a position that is otherwise occupied by a two-place predicate, as illustrated by (19a) and (19b), with (19c) as a reference for the discussion.

(19)

a. Wǒ de yí gè péngyǒu, zhǎng dé hěn shuài.

1st.sg de one cl friend, look prt very handsome

‘I have a friend, looking very handsome.’

b. Wǒ yǒu yí gè péngyǒu, zhǎng dé hěn shuài.

1st.sg have one cl friend, look prt very handsome.

‘I have a friend, looking very handsome.’

c. *Wǒ yǒu de yí gè péngyǒu, zhǎng dé hěn shuài.

1st.sg have de one cl friend, look prt very handsome.

‘I have a friend, looking very handsome.’ [intended]

In (19a), wǒ de is conventionally regarded as a syntactic combination of the first person pronoun wǒ with a clitic de, which functions like the possessive pronoun my in English, as mentioned before. According to this conventional view, wǒ de yí gè péngyǒu is the grammatical subject of sentence (19a) and zhǎng dé hěn shuài is the predicate. Nevertheless, it should be noted that the sentence can be paraphrased as (19b), in which the possessive relationship is expressed by the verb yǒu ‘have’. The structural analysis of (19b) is a thorny issue. One possible analysis is that wǒ yǒu yí gè péngyǒu is a clause and zhǎng dé hěn shuài is another clause, the semantic subject of which is ‘a friend of mine’ or literally ‘a friend that I have’. In other words, the first clause in (19b) very likely is a noun phrase consisting of the head yí gè péngyǒu ‘a cl friend’ and a relative clause wǒ yǒu ‘1st.sg have’, which does not carry the modification marker de. It is not uncommon that in some cases a relative clause does not carry the modification marker de although in many cases de is present. Compare (20a), where the modification marker de occurs and (20b) where the marker does not occur.

(20)

a. Wǒ mǎi de nà běn shū hěn piányi.’

1st.sg buy de that cl book very cheap

‘That book which I bought is very cheap.’

b. Wǒ mǎi nà běn shū hěn piányi.

1st.sg buy that cl book very cheap

‘That book which I bought is very cheap.’

Assuming that (19b) involves an ellipsis of de, it is expected that de could be recovered in it; but the co-occurrence of yǒu and de results in ungrammaticality, as shown in (19c). An explanation of the ungrammaticality is that in such a case, de has obtained some property of a predicate and competes with yǒu for the same syntactic function, although de itself is semantically underspecified.

The second piece of evidence for this hypothesis comes from the use of de in oral calculation. On some occasions, de occurs where the word chéng occurs. The word chéng expresses multiplication calculation involving two numbers, for example (21a).

(21)

a. Èrshí wŭ de èrshí wŭ, lìu bǎi èrshí wŭ.

twenty five de twenty five, six hundred twenty five

‘Twenty five multiplied by/times twenty five is six hundred and twenty five.’

b. Èrshí wŭ chéng èrshí wŭ, lìu bǎi èrshí wŭ.

twenty five multiplied.by/times twenty five, six hundred twenty five

‘Twenty five multiplied by/times twenty five is six hundred and twenty five.’

Sentence (21a) can be straightforwardly paraphrased by sentence (21b).Footnote 5 Where de occurs in (21a) is exactly where chéng ‘multiplied by/times’ occurs in (21b).

Interestingly, on other occasions, speakers use de to express addition calculation, illustrated by (22a), with (22b) as a paraphrase.

(22)

a. Èrshí wŭ de èrshí wŭ, wŭshí.

twenty five de twenty five, fifty

‘Twenty five plus twenty five is fifty.’

b. Èrshí wŭ jiā èrshí wŭ, wŭshí.

twenty five plus twenty five, fifty

‘Twenty five twenty five is fifty.’

(21) and (22) illustrate a case where the semantically underspecified de obtains its semantic content via context-based semantic enrichment.Footnote 6 Since de is either interpreted as multiplication or addition when it occurs between two numeral phrases, its interpretation heavily depends on the context in which it appears. Such facts are similar to (8a) and (8d), repeated below as (23a) and (24a), where de can be paraphrased by a two-place verb, as is illustrated by (23b) and (24b).

(23)

a. Zhāngsān de lánqiú dǎ dé hǎo. [=(8a)]

Zhangsan de basketball play prt good

‘Zhangsan plays basketball well.’

b. Zhāngsān dǎ lánqiú dǎ dé hǎo.

Zhangsan play basketball play prt good

‘Zhangsan plays basketball well.’

(24)

a. Zhèi dùn fàn, Zhāngsān de dōngjiā. [=(8d)]

this cl meal Zhangsan dehost

‘As for this meal, Zhangsan acts as the host.’

b. Zhèi dùn fàn, Zhāngsān dāng dōngjiā.

this cl meal Zhangsan act.as host

‘As for this meal, Zhangsan acts as the host.’

In another sentence, which has the same structure as (24a)[=(8d)], de is paraphrased by yǎn ‘play as’, as shown in (25a) and (25b).

(25)

a. Zhèi chǎng xì Méi Lánfāng de Yújī.

this cl opera Mei Lanfang de Yuji

‘In this opera, Lanfang Mei played as Princess Yuji.’

b. Zhèi chǎng xì, Méi Lánfāng yǎn Yújī.

this cl opera, Mei Lanfang act.as Yuji

‘In this opera, Lanfang Mei played as Princess Yuji.’

It should be noted that de in (8b) cannot be straightforwardly interpreted as a predicate. But (8b) has a variant, given above as (9) and repeated below as (26a). The morpheme de in (26a) can be paraphrased by a full verb, as shown in (26b).

(26)

a. Zhāngsān de bù pǎo-le sān fēnzhōng [=(9)].

Zhangsan de step run-ASP three minute

‘Zhangsan ran for three minutes.’

b. Zhāngsān pǎo bù pǎo-le sān fēnzhōng.

Zhangsan run step run-ASP three minute

‘Zhangsan ran for three minutes.’

This indirectly shows that de in (8b) can be paraphrased by a full verb. Unlike (8a), (8b), and (8d), in which de can be somehow paraphrased by a full verb, (8c), repeated as (27a), does not have a corresponding paraphrasing sentence. But it still can be assumed that de therein is a semantically underspecified predicate. If de is replaced by a full verb, although the resulting sentence as a whole is weird, neither of the parts indicated by the separating ‘||’ in (27b) is unacceptable.

(27)

a. Zhāngsān dǎ Zhāngsān de lánqiú, (Lǐsì pǎo Lǐsì de bù.) [=(8c)]

Zhangsan play Zhangsan de basketball, Lisi run Lisi de step

‘Zhangsan plays basketball and Lisi runs [they do not interfere with each other].

b. *Zhāngsān dǎ || Zhāngsān dǎ lánqiú, (Lǐsì pǎo || Lǐsì pǎo bù.)

Zhangsan play || Zhangsan play basketball, (Lisi run || Lisi run step)

‘Zhangsan plays basketball and Lisi run.’

Although it seems that simply repeating a full verb is dispreferred, assuming de as a semantically underspecified predicate that expresses what a full verb expresses does not go against any empirical fact.

Additionally, it is likely that this use of de occurs as a result of degrammaticalization (Norde Reference Norde2009), wherein de changes from a pure functional clitic to a semantically underspecified two-place predicate either by reanalysis, in which de absorbs some property of some adjacent predicate that no longer appears, or by analogy because de happens to appear in a position where a two-place predicate can appear. In fact, the thought that de is a semantically underspecified two-place predicate has been suggested before. As mentioned in the literature review, Mei (Reference Mei1978) proposes that de is inserted in a position where a verb is deleted but, unfortunately, he does not clarify the syntactic and semantic properties of de in this case.Footnote 7

To sum up, the above observation reveals that de has the status that a verb typically has, but it is semantically underspecified in the sense that its specific semantic content is contextually enriched.

4.2 The syntactic restrictions concerning de

The semantic underspecification of de determines that the morpheme is context-dependent semantically, either obtaining its semantic content from a preceding context, for example (8b) and (8c), or from a later context, e.g., (8a) or from the speaker's world knowledge such as (8d), (22a), and (22b). Apart from being semantically context-dependent, the morpheme is also syntactically dependent. In (8a), de requires the occurrence of its grammatical subject and object, and it also requires the presence of the verb and a postverbal adverbial. In (8b) and (8c), where the linear position of de is different from that in (8a), the word has other requirements on what can or cannot appear before or after it. The examples in (28) illustrate the syntactic restrictions concerning de.Footnote 8

(28)

a. *(Zhāngsān) de *(lánqiú) *(dǎ) *(dé hǎo).

Zhangsan de basketball play prt good

b. Zhāngsān de lánqiú (*Zhāngsān) dǎ dé hǎo.

Zhangsan de basket Zhangsan play prt good

c. Zhāngsān dǎ sān tiān (*Zhāngsān) de lánqiú.

Zhangsan play three day Zhangsan de basketball

d. Zhāngsān dǎ (*sān tiān) Zhāngsān de lánqiú.

Zhangsan play three day Zhangsan de basketball

Sentence (28a) shows that de requires the presence of its grammatical subject, grammatical object, the verb, and some following adverbial expressions, such as dé hǎo. The absence of any one of these expressions results in ungrammaticality. Sentence (28b) shows that the presence of de does not allow dǎ dé hǎo to be immediately preceded by a local subject. Sentences (28c) and (28d) jointly show that the postverbal adverbial and the local subject cannot co-occur. In the generative accounts reviewed above, the significance of the presence of dé hǎo for the well-formedness of (28a) and (28b) is simply ignored, since the theoretical tools in those accounts cannot accommodate the requirement of the presence of a postverbial adverbial that de imposes. Briefly, a number of facts regarding de and fake modification constructions in which it appears can hardly be explained by any general rules in Generative Grammar. Instead, it seems that de turns out to be different morphemes in different fake modification constructions, because its presence in these various constructions is syntactically constrained in different ways and imposes constraints on other expressions in different ways, although in each fake modification construction, de always contributes a semantically underspecified predicate. In the following section, a formal characterization of fake modification constructions is proposed, where the common contribution to semantic interpretation and the syntactic peculiarities of different de-morphemes are captured in parallel as part of parsing processes.

5. A Parsing Account of Fake Modification Constructions

The semantic underspecification and update and syntactic restrictions concerning de exhibit themselves in dynamic processes of expressing propositional meanings by uttering strings of words. A string of words that is used for communication is a grammatical sentence only if it is parsable. Hence, the grammaticality of a sentence can be defined as its parsability and seen from the parsing perspective, the grammar of a language is the procedural actions that are directly employed in parsing. This is the very linguistic philosophy of Dynamic Syntax (Kempson et al. Reference Kempson, Meyer-Viol and Gabbay2001; Cann et al. Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005). This section is devoted to proving such a parsing account of the constructions at issue in the framework of Dynamic Syntax. The framework is briefly introduced first in 5.1. For more details, see Kempson et al. (Reference Kempson, Meyer-Viol and Gabbay2001), Cann et al. (Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005), Gregoromichelaki and Kempson (Reference Gregoromichelaki, Kempson, Capone, Piparo and Marco2013), Kempson et al. (Reference Kempson, Cann, Eshghi, Gregoromichelaki, Purver, Shalom and Fox2015), Kempson et al. (Reference Kempson, Cann, Gregoromichelaki and Chatzikyriakidis2016), Gregoromichelaki and Kempson (Reference Gregoromichelaki, Kempson, Scott, Clark and Carston2017), among many other Dynamic Syntax studies. The parsing account of the fake modification constructions is given in 5.2.

5.1 Essentials of Dynamic Syntax

In Dynamic Syntax, well-formed sentences are parsable strings of words. The parse of a string of words is aimed to construct a propositional formula. It is hypothesized that a parsing process involves the application of some general computational rules that induce the construction of semantic structures, lexical information of words parsed one by one, contextual information relevant to an ongoing parsing process, and pragmatic inference triggered either verbally or non-verbally. A parsing process is an informationally incremental process, where what has been used can be reused, and it is also a process where semantic underspecification and update keep happening, which means that initially, some semantic content does not have fixed status or some expressions do not have specific semantic content and semantic underspecification is updated in later parsing stages.

Technically, Dynamic Syntax employs the Logic of Finite Trees (Blackburn and Meyer-Viol Reference Blackburn and Meyer-Viol1994), a modal logic which describes binary branching tree structures, reflecting the mode of semantic combination in the form of functional application. The monotonic growth of a partial semantic tree is employed to represent stepwise accumulation of semantic content obtained from linearly parsed words and relevant context. Next, (29) is used as an example to demonstrate how the parsing process unfolds and how computational rules and lexical information are employed in the parsing process, and to introduce some basic assumptions that are adopted in the following account of fake modification constructions.

(29) Zhāngsān dǎ lánqiú.

Zhangsan play basketball

‘Zhangsan plays basketball.’

The parsing process starts with setting up the initial goal of constructing a proposition on the root node of a partial semantic tree. The initial goal is represented by ?t, where ‘?’ stands for the requirement of a formula and ‘t’ stands for the truthvalue type of a formula, i.e., a proposition. New tree nodes are created as a result of applying general computational rules or lexical actions. Tree nodes accommodate semantic content obtained from scanned words or context. A tree node under construction is indicated by♢, called the pointer. The pointer moves from one tree node to another as the parsing process unfolds and more and more tree nodes are created and constructed one by one. When a tree node initially has a requirement to be met, the requirement must be satisfied somehow; otherwise, the parsing process cannot be successfully accomplished. As the requirements on all terminal tree nodes are satisfied, the semantic formulae on sister nodes combine through functional application to satisfy the requirements on the immediately dominating tree nodes until there is no outstanding requirement on any tree node, a state in which the utmost goal is achieved.

The parsing process starts with setting the initial goal ?t of a partial semantic tree, the address of the root node being Tn(n), which is either Tn(0), i.e., a node dominated by no other node, or some node properly dominated by Tn(0) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Setting the initial goal

After the initial goal is set, the LOCAL *ADJUNCTION rule is applied, which has the effect of creating an e-type unfixed node,Footnote 9 which is an argument daughter node of a predicate node somewhere below Tn(n). The LOCAL *ADJUNCTION rule is motivated by the fact that in Mandarin Chinese, an expression that contributes an argument-type formula does not initially get fixed a semantic status in the propositional formula to be constructed, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: After applying LOCAL *ADJUNCTION

Presently, the pointer is on an e-type node. The goal e can be achieved by scanning the lexical item Zhāngsān, the semantic content of which is simply represented as ‘zhangsan′’. By convention, contentful formulas are all represented in this way (See Figure 4).

Figure 4: After scanning Zhangsan

As the requirement on the argument node is satisfied, the pointer moves upward through applying the rule of COMPLETION (See Figure 5) (Cann et al. Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005, 50).Footnote 10

Figure 5: Applying COMPLETION

At this stage, the lexical item dǎ ‘play’ is scanned, which provides lexical information. In Dynamic Syntax, lexical information consists of triggering conditions and lexical actions. The ‘IF’ clause expresses triggering conditions; the ‘THEN’ clause delivers lexical actions to be taken if triggering conditions are met and the ‘ELSE’ clause provides lexical actions when triggering conditions are not met.

(30) The lexical information of dǎ Footnote 11

There are two conditions in the lexical information of dǎ. The first condition is the pointer is on a node with a type t requirement. The second condition is there is an e-type unfixed node. The lexical actions that dǎ contributes include ‘MAKE()’, ‘PUT()’, ‘’GO() and ‘ABORT’. The function of ‘MAKE()’ is to create a node; the tree modal relationship between the current node and the node to be created is given as the argument of ‘MAKE()’. The tree modal operators ‘⟨↓⟩’ and ‘⟨↑⟩’ respectively point to the mother node or the daughter node of a node at issue and the subscripts ‘0’ and ‘1’ indicate the logical type of node pointed to. ‘0’ means that the node pointed to is an argument node and ‘1’ means that the node pointed to is a functor node. The Kleene star ‘*’ is used to express some underspecified tree node relation. For example ⟨↑*⟩Tn(n) expresses a node that is somewhere below the root node Tn(n). The tree modal operators can be used successively to indicate the tree modal relationship between any two nodes on the same semantic tree. The function of ‘GO()’ is to move the pointer from the current node to another node and the tree modal relationship between the current node and the node to which the pointer moves to is given as the argument of ‘GO()’. ‘PUT()’ annotates a node with some lexically provided semantic content or requirements. The action ‘ABORT’ is responsible for terminating a parsing process. All linguistic expressions, including lexical items and clitics, contain lexical actions.Footnote 12 To continue, as the word dǎ is parsed, the lexical actions that the word contributes update the partial semantic tree. When the triggering conditions are satisfied, the word constructs an unfixed node that dominates two nodes, annotates the functor type daughter node with a semantic formula, and drives the pointer to the e-type node created as a result of applying lexical actions. The assumption that the lexical actions of dǎ create an unfixed node is motivated (see Figure 6) by the fact that content verbs in Chinese can be used either finitely or non-finitely, and when they occur, their semantic status in a propositional formula under construction is not fixed initially.

Figure 6: After parsing Zhangsan da

Following dǎ, Lǐsì is parsed, which updates the partial tree, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7: After parsing Zhangsan da Lisi

Next, at this stage, two rules are applied consecutively. The COMPLETION rule moves the pointer up from a daughter to a mother and annotates the mother node with the information that it indeed has a daughter with certain properties. The ELIMINATION rule takes the formulae on two daughter nodes, performs functional application over these and annotates the mother node with the resulting formula and type, thus satisfying an outstanding type requirement on the non-terminal mother node. Then, the INTRODUCTION and PREDICTION rules are applied sucessively, which construct a tree structure to accommodate semantic components of a propositional formula. By applying the ANTICIPATION rule, the pointer moves to the type (e→t) →(e →(es →t)) node, which is assumed to be there to accommodate the semantic content from an adverb that semantically modifies the verb, if available, or to accommodate an identity functor if no such adverb is available (see Figure 8). An identity functor, similar to a metavariable, does not have conceptual content, but unlike a metavariable, which obtains conceptual content from context, it takes a concept obtained through parsing as its argument to yield the same concept as the result of semantic combination. In the current case, the identity functors represent the lack of an adverb that modifies a predicate. The appearance of the identity functor in a partial tree is achieved through applying the IDENTITY FUNCTOR INSERTION rule (given in the Appendices).

Figure 8: After applying INTRODUCTION and PREDICTION repeatedly

With the propositional template constructed, a few fixed nodes with logical type requirements are available. At this parsing stage, the previously constructed unfixed nodes unify with some of the newly created fixed nodes on the condition that they have the same logical types. The process of an unfixed node and a fixed node unifying is achieved via the action of UNIFICATION, which is indicated by the dashed curves in Figure 8. This operation has the effect of satisfying some, if not all, requirements on both the unfixed node and the fixed node at issue.

Next, since the requirements on the node under construction are satisfied, the COMPLETION and ELIMINATION rules are applied routinely. The pointer moves upward and the semantic formulae on the sister nodes combine, providing composite semantic values for mother nodes (Cann et al. Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005, 52). The metavariable on the type es node (event argument node) is replaced by a free variable s, which happens as a result of pragmatic inference and has the result of specifying an event that is predicated by the proposition to be accomplished (see Gregoromichelaki Reference Gregoromichelaki2006, Reference Gregoromichelaki, Kempson, Gregoromichelaki and Howes2011, for more details about the significance of the event argument). Finally, all the requirements on the tree are satisfied and a propositional formula is obtained on the root node, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9: After applying the COMPLETION and ELIMINATION rules repeatedly

The above parsing process illustrates how general computational rules work and what happens when a word is parsed while parsing Chinese sentences. These theoretical tools are employed in characterizing the parsing of the fake modification constructions, along with three LINK-related rules, which are introduced where they are employed. (See Gregoromichelaki and Kempson Reference Gregoromichelaki, Kempson, Capone, Piparo and Marco2013, Reference Gregoromichelaki, Kempson, Capone and Mey2015; Kempson et al. Reference Kempson, Cann, Gregoromichelaki and Chatzikyriakidis2016; Gregoromichelaki and Kempson Reference Gregoromichelaki, Kempson, Scott, Clark and Carston2017; Gregoromichelaki Reference Gregoromichelaki, Saka and Johnson2018, for more on the latest technical and theoretical notions in Dynamic Syntax).

5.2 The dynamics of de in fake modification constructions

The four sentences (8a)-(8d), repeated below in each subsection to facilitate readers’ following the formal characterization, are used as examples to illustrate what contribution de makes to semantic interpretation in parsing the fake modification constructions. I show that the syntactic constraints on the occurrence of de in the fake modification constructions are different from each other and for this reason, different de-morphemes are recognized, even though they make rather similar semantic contribution.

5.2.1 Zhangsan de lanqiu da de hao ‘Zhangsan plays basketball well’

(30) Zhāngsān de lánqiú dǎ dé hǎo. [=(8a)]

Zhangsan de basketball play de good

‘Zhangsan plays basketball well.’

The DS characterization of how (30) is parsed goes as follows. First, the initial goal ?t is set on Tn(n). The words to be parsed make two propositions. each of which, semantically, is not embedded in but related to the other. This situation is similar to the case of a relative clause and a matrix clause, or to the case of two conjoined clauses; the mechanism of connecting two partial trees, LINK, is employed (Kempson et al. Reference Kempson, Meyer-Viol and Gabbay2001; Cann et al. Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005). The LINK relationship is represented by a pair of modal operators, ⟨L⟩ and ⟨L −1⟩; the former ‘points’ to a tree linked to the current node on the matrix tree and the latter ‘points backwards’ to that node. If a node of the first tree has the address Tn(n), the root node of the LINKed tree that LINK points to has the address ⟨L −1⟩ Tn(n). Finally, the semantic content on the two partial trees are integrated through applying the rule of LINK EVALUATION. Since de cannot function as the predicate of a contextually independent sentence/clause, the information that the string Zhāngsān de lánqiú is accommodated on the LINKed tree, similar to that of a relative clause, the interpretation of which is dependent on another clause, even though it has a full clausal structure.

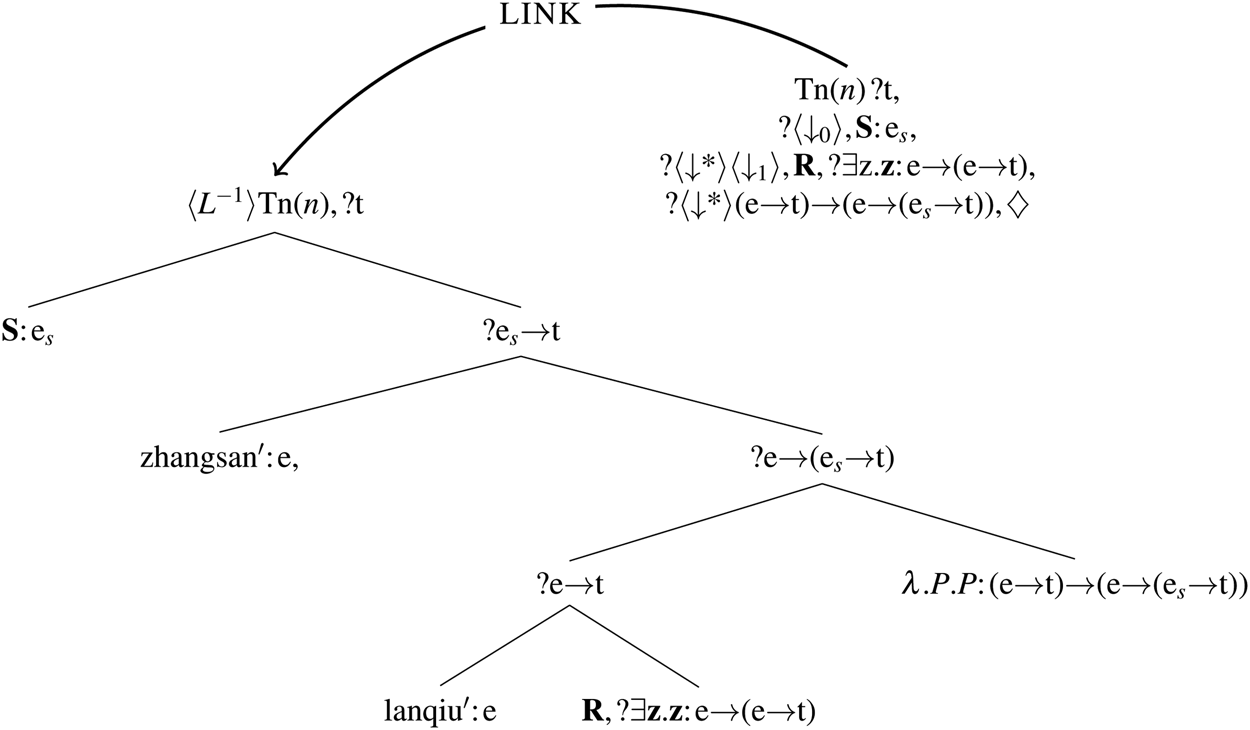

The parsing process starts with setting the root node of a main tree and then LINK ADJUNCTION is applied under the condition of ?t on the root node of the main tree, giving rise to the LINK relationship between the root nodes of two partial trees, one being the main tree and the other, the LINKed tree. The pointer is moved to the root node of the LINKed tree. At this stage, LOCAL *ADJUNCTION is applied, creating an e-type unfixed node, and then Zhāngsān is processed. After these operations, the partial tree grows into the state shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10: After parsing Zhangsan

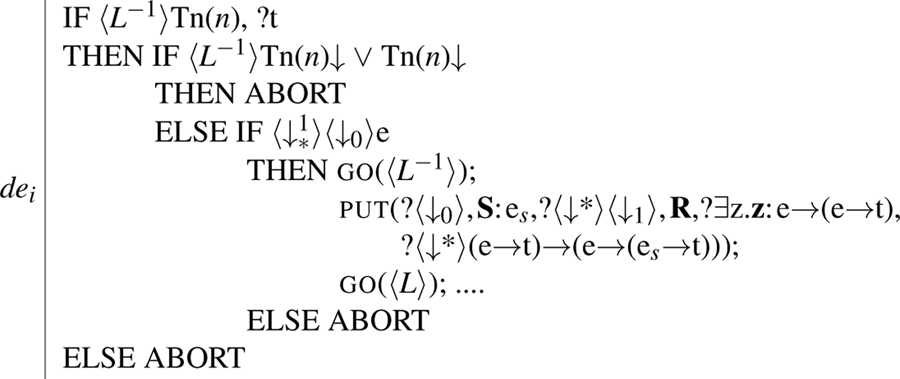

Now, the lexical item de is processed. The above description shows that de appears in different positions in the different fake modification constructions. To capture this fact, I assume that de can be parsed under different conditions. In the current case, the conditions under which de (referred to as dei) contributes lexical actions are that the pointer is located on the root node of a tree LINKed to the root node of a main tree, which does not have any daughter nodes yet and under the current node of the LINKed tree, there is an unfixed node that accommodates an e-type formula and there are no other daughter nodes. Once the triggering conditions in dei are satisfied, the lexical actions in dei are triggered. The lexical actions include those that construct a propositional template, which are given in (32) and are referred to as ‘…’ henceforth, and those which impose some requirements on the growing tree(s).

(32) Lexical actions that the de-morphemes at issue commonly contribute

(33) The lexical information of dei

The effect of parsing dei and that of applying UNIFICATION are shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11: After parsing Zhangsan de

As a result of parsing dei, the pointer is now located on the internal argument node on the LINKed tree. This allows lǎnqíu ‘basketball’ to be parsed, which annotates the current node with an e-type formula. Then the LINK ANTICIPATION rule is applied, pushing the pointer to the root node of the main tree, as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12: After parsing Zhangsan de lanqiu

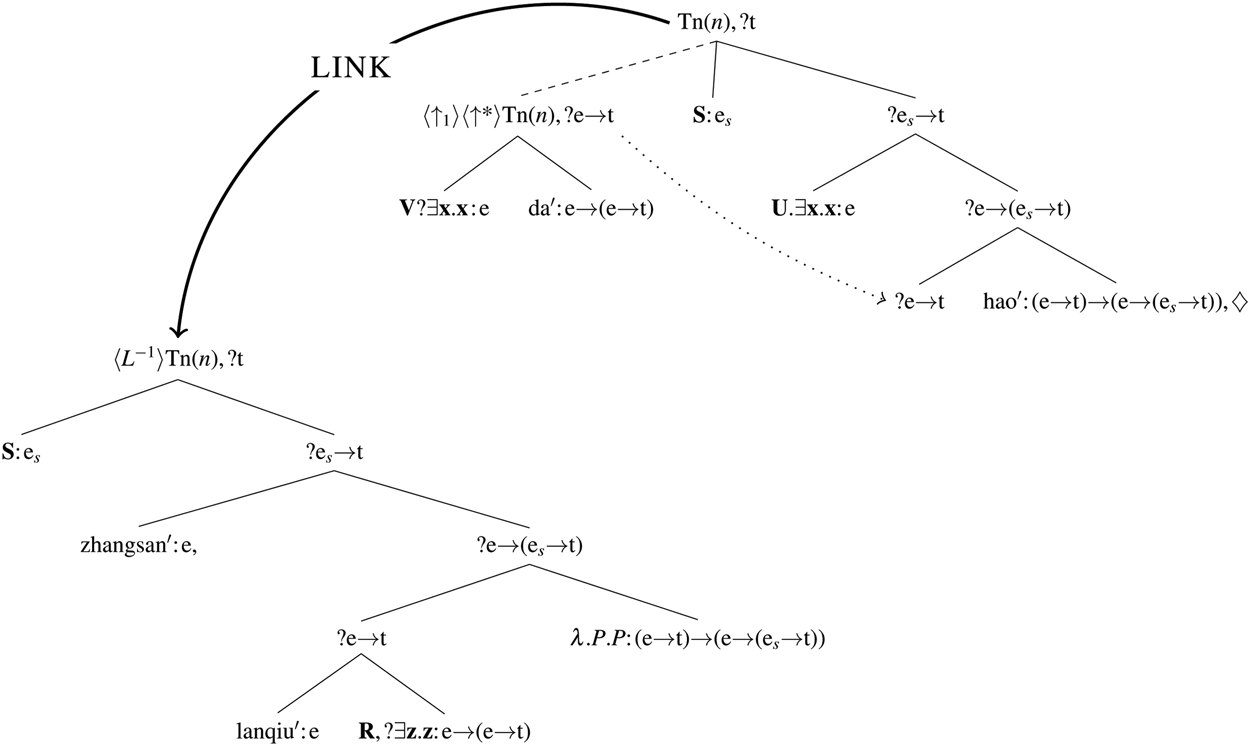

Then dǎ ‘play’ is scanned, projecting an unfixed node that dominates two daughter nodes, including an e-type one that is annotated with a metavariable. The pointer goes back to the root node of the main tree as a result of applying ANTICIPATION, as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13: After parsing Zhangsan de lanqiu da

Next, the postverbal dé is parsed, which requires that a clause has already been parsed; however, the clause already parsed cannot have a postverbal object and also requires that after the objectless clause is a verb without an explicit subject. The lexical information of dé is defined as follows.

(34) The lexical information of the postverbal particle dé

The two conditions, ‘p:t’ and ‘‘[(⟨↓*⟩⟨↓1⟩⟨↓0⟩⟨↓⟩)β :(e→t)(e→(es→t))] ∨ [(⟨↓∗1⟩⟨↓0⟩)α:e]’ together wtih the ABORT in the same scope of IF, have the function of ensuring that dé immediately follows a proposition that has already been constructed and ensuring that it is not immediately preceded by a noun phrase, excluding the ungrammatical string such as Zhāngsān dǎ lánqiú dé hǎo ‘Zhangsan play basketball prt good’ or Zhāngsān dǎ Zhāngsān dé hǎo ‘Zhangsan play Zhangsan PRT good’. The condition simply states that if there is a locally constructed argument formula that has daughter nodes, the parse is terminated. In the current case, the internal argument node, where ‘lanqiu′’ occurs, does not have daughter nodes because the formula ‘lanqiu′’ is not locally constructed through parsing a word, but rather comes from the context (see Figure 14).

Figure 14: After parsing Zhangsan de lanqiu da de

After the postverbal dé is scanned, the current partial tree is updated, as shown in Figure 14, where the requirement ?⟨↓*⟩(e→t)→(e→(es→t)) is satisfied by the construction of such a node through applying the lexical actions of hǎo. At the same time, the unfixed node on the current tree unifies with the lower e→t type node. The requirements of constructing some nodes below the root node of the current tree are all satisfied (see Figure 15).

Figure 15: After parsing Zhangsan de lanqiu da de hao

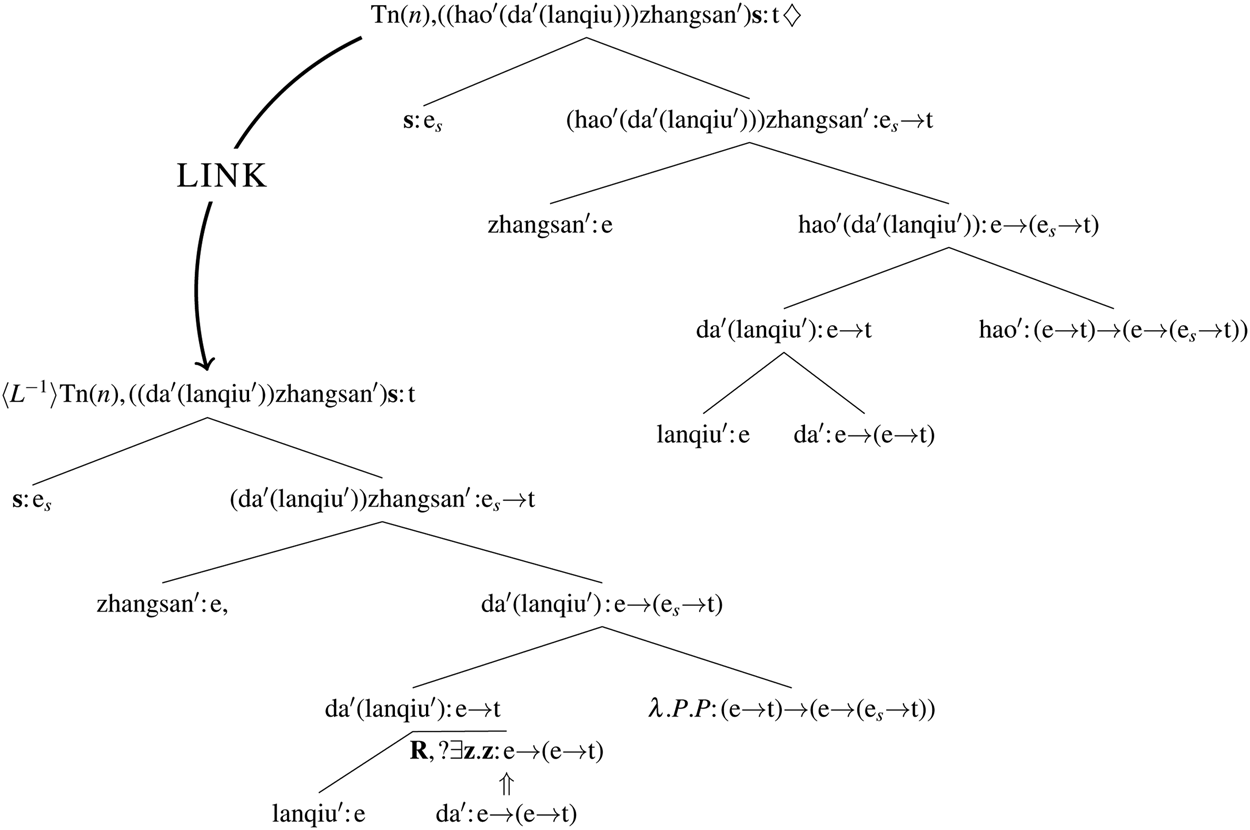

The COMPLETION and ELIMINATION rules are applied; a metavariable is inserted in the open e-type node and the semantic content of the metavariable comes from the latest context. The metavariable S on the current node is replaced by the free variable s. The metavariables U and V are replaced by contentful formulae from the latest context. The pointer goes back the LINKed tree, where there are still requirements to be satisfied. The pointer goes down to the bottommost node first. The metavariable R is replaced by the semantic content of dǎ; then the pointer moves upward as the COMPLETION rule is applied several times (see Figure 16).

Figure 16: After parsing Zhangsan de lanqiu da de hao

As the root nodes of two LINKed semantic trees obtain formulae, the rule of LINK EVALUATION (Cann et al. Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005, 92)) is applied. The propositional formulae on the root nodes of the two trees combine into a compound propositional formula, given as (35).

(35) ((((da′(lanqiu′))zhangsan′)s)∧(((hao′(da′(lanqiu')))zhangsan′)s)

As shown above, in the parsing process, dei contributes a semantically underspecified predicate, the semantic content of which is specified through inference (see Cann et al. Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005 for a similar treatment of be in English). Besides, the definition of dei at issue also captures the fact that its presence imposes requirements and constraints on words parsed later. To save space, the following demonstrations only include the state of partial trees before metavariable substitution, COMPLETION, and ELIMINATION rules are applied. Details before and following the presented state are omitted because they are similar to those given above, .

5.2.2 Zhangsan pao-le san fenzhong de bu ‘Zhangsan ran for three minutes’

(36) Zhāngsān pǎo-le sān fēnzhōng de bù. [=(8b)]

Zhangsan run-ASP three minute de step

‘Zhangsan ran for three minutes.’

The process of parsing (36) is demonstrated below. The string Zhāngsān pǎo le sān fēnzhōng is parsed just like an ordinary simple clause. After this, a LINK relation is constructed between the root node of the current tree and the root node of a LINKed tree. Then, de (here referred to as deii) and bù are parsed one by one. The triggering conditions and the lexical actions in deii are different from those in dei. In the current case, the triggering conditions consist of three parts: (i) the pointer is located at root node of the LINKed tree; (ii) there exists a propositional formula on the root node of the main tree, which consists of an argument subject, a predicate, and an adverbial; (iii) there is no e-type unfixed node under the root node of the LINKed tree. The lexical actions of deii includes constructing a propositional template but does not include imposing some requirements on the growing trees.

(37) The lexical information of deii

Via parsing deii and bù ‘step’, the partial trees are updated, as shown in Figure 17.

Figure 17: After parsing Zhangsan pao le san fenzhong de bu

By applying the COMPLETION and ELIMINATION rules, the propositional formula (38) is obtained.

(38) ((san fenzhong′(pao′(bu′)))zhangsan′)s

As is seen in the above demonstration of the parsing process, sān fēnzhōng de bù ‘three minute de step’ is not a nominal expression as is assumed in the literature; instead, de is a predicate, taking bù as its object complement. To reiterate, there is no relation of modification between sān fēnzhōng and bù.

5.2.3 Zhangsan da Zhangsan de lanqiu ‘Zhangsan played baskedball’

(39) Zhāngsān dǎ Zhāngsān de lánqiú. [=(8c)]

Zhangsan play Zhangsan de basketball

‘Zhangsan played basketball.’

In the beginning, the parse of Zhāngsān dǎ leads to the construction of a partial tree, which includes an internal argument node with an outstanding e-type requirement, which is provisionally satisfied by inserting an e-type metavariable. The pointer goes back to the root node of the current tree; then a LINK relationship is constructed between the root node of the current tree and that of a LINKed tree. Then, LOCAL *ADJUNCTION is applied, constructing an unfixed node with an e-type requirement. The e-type requirement is then satisfied through parsing Zhāngsān. Then de (here referred to as deiii) is parsed. Apparently, the triggering conditions of the lexical actions in deiii are different from those in the case of dei and deii, specifically including there being no fixed node under the current node, and the root node of the main tree dominating an external argument node with an e-type formula, an internal argument node with an e-type formula and an adverbial functor node with an identity functor.

(40) The lexical information of deiii

After parsing deiii, UNIFICATION is applied. The effects of the two parsing steps are given in Figure 18.

Figure 18: After parsing Zhangsan da Zhangsan de lanqiu

After COMPLETION, LINK COMPLETION, and ELIMINATION are applied repeatedly to the partial trees, the propositional formula (41a) is yielded on the root node of the main tree. The two conjuncts of (41a) are identical and therefore the final semantic representation obtained by this process is (41b).

(41)

a. (((da′(lanqiu′))zhangsan′)s)∧(((da′(lanqiu′))zhangsan′)s)

b. (((da′(lanqiu′))zhangsan′)s)

The process of constructing one and the same simple proposition twice does not make semantic contribution, but it produces the effect of emphasizing the proposition at issue.

5.2.4 Zhei dun fan, Zhangsan de dongjia ‘as for this meal, Zhangsan is the host’

Finally, the fake modification construction that involves a dangling topic is analyzed. The example is repeated below for ease of observation.

(42) Zhèi dùn fàn, Zhāngsān de dōngjiā. [=(8d)]

this cl meal, Zhangsan de host

‘As for this meal, Zhangsan is the host.’

In parsing (42), zhèi dùn fàn provides semantic content for an e-type node somewhere below the root node of a partial tree. It should be noted that the assumption that the dangling topic zhèi dùn fàn provides semantic content for a partial tree LINKed to the partial tree for which the comment provides semantic content is motivated by the observation that the dangling topic may have its own predicate in some cases. See the following example.

(43) Zhèi dùn fàn hěn zhòngyào, Zhāngsān de dōngjiā.

this cl meal very important, Zhangsan de host.

‘This meal is important, (for) Zhangsan will act/acted as the host.’

In this example, the dangling topic appears as the subject of the first clause, followed by the second clause, which appears as the comment in (43). This assumption also has a theoretical bonus: the semantic content of the dangling topic appears on a main tree, providing a LINK context for the parse of de, which is similar to the parse of the other two fake modification constructions where de appears in the second clause.

Next, LINK ADJUNCTION is applied, imposing the requirement of locating a copy of the content of zhèi dùn fàn somewhere on the LINKed tree. After this, zhāngsān de dōngjiā is parsed. The semantic content of zhāngsān appears initially on an e-type unfixed node that is created through applying LOCAL *ADJUNCTION. Then, de (here referred to as deiv) is parsed, which contributes a propositional template, just as dei, deii, and deiii do. The triggering conditions are that the pointer is located at the root node of a LINKed tree, which does not have any fixed daughter nodes, that the root node of the main tree has an e-type daughter node which has already been annotated with a formula and a functor daughter node, which is provisionally annotated with a metavariable, and that there is an e-type unfixed node annotated with a formula under the root node of the current node.

(44) The lexical information of deiv

After deiv is parsed, the e-type unfixed node, where the semantic content of zhāngsān is located, and the external e-type argument node on the propositional template collapse into each other as UNIFICATION is applied. Through pragmatic inference, the metavariable projected by de is replaced by a semantically contentful formula. The partial trees are updated as follows, where, on the LINKed tree, λy.CIR(y) is pragmatically introduced into the scene as a functor that expresses the circumstance status assigned to ι,x.fan′(x) and the metavariable R projected by de is replaced by a contentful formula through pragmatic inference, which is semantically equivalent to ‘dang′’(act.as′). The overall effect of the above parsing stages is demonstrated in Figure 19.

Figure 19: After parsing Zhei dun fan, Zhangsan de dongjia

Next is the application of the COMPLETION and ELIMINATION rules and metavariable substitution. Then the pointer goes back to the main tree. I assume that the structure of the LINKed tree is reused (Gargett et al. Reference Gargett, Gregoromichelaki, Howes and Sato2008) to complete the main tree, which provides a fixed node with which the unfixed node where ι,x.fan′(x) is located unifies. After the LINK EVALUATION rule is applied, the following propositional formula is obtained (45).

(45) (((CIR(ι, x.fan′(x))(dang′(dongjia′)))zhangsan′)s

This parsing process involves two types of semantic underspecification. First, the semantic relation between zhèi dùn fàn ’this CL meal’ and the rest of the sentence is not marked linguistically but rather is established by pragmatic inference.Footnote 13 Second, the semantically underspecified predicate cannot obtain its semantic content without the context in which the string uttered is parsed. Without the context, zhèi dùn fàn ‘thisCL meal’, Zhāngsān de dōngjiā can barely be interpreted as ‘Zhangsan acted as the host’. The context, zhèi dùn fàn ‘thisCL meal’ helps exclude the possibility that Zhāngsān de dōngjiā is interpreted as a nominal phrase involving a possessive relation between the modifier and the head; if the string of three words is parsed this way, the string zhèi dùn fàn, Zhāngsān de dōngjiā is meaningless.

In this way, the generation of all the four fake modification constructions at issue has been characterized as parsing processes. In this account, no deletion, movement, or empirically problematic assumption of a gerund phrase is involved. Instead, words are processed one by one, contributing actions and formulae, to construct propositional formulae. However, it should be noted that in the current account of the fake modification constructions, four different de-morphemes are recognized, which were referred to as dei, deii, deiii, and deiv. Distinguishing the four de-morphemes is empirically justified because the lexical actions that the four morphemes contribute are merely similar rather than identical.

6. Conclusion

Fake modification constructions have long puzzled linguists of Chinese, who, on the one hand, acknowledge that there is no evidence that de and the two expressions which respectively precede and follow de constitute a phrase but, on the other hand, cannot break the mindset that de is an modification marker. The previous accounts, formulated in the framework of Generative Grammar, suffer from various theoretical problems and empirical challenges such as mysterious empty categories, poorly motivated deletion and movement, and mysterious insertion of morphemes; they even simply leave unaccounted for the obligatory appearance of some constituents in these constructions. This paper solves the puzzle posed by fake modification constructions, showing that the fake modification in these construction is really fake, there being no relation of modification between the two noun phrases that precede and follow de, and proposes a new account of the generation of fake modification constructions from a parsing perspective, revealing that fake modification constructions involve different de-morphemes with different syntactic properties, though all contribute a semantically underspecified predicate. This paper exposes a new case of semantic underspecification, enlarging the scope of the investigation of semantic underspecification in natural languages. Besides, the current account of de-morphemes, with the theoretical tools in Dynamic Syntax, can properly capture the syntactic idiosyncrasies, which, as far as I can see, can hardly be accurately captured in the accounts developed in the generative framework. The restricted ability of the generative accounts in integrating the characterization of idiosyncratic syntactic properties of individual words in a so-called ‘principled’ account arises due to the gap between the peculiar properties and the categorial properties of words. Compared with generative accounts, the current account in Dynamic Syntax entertains general computational rules and lexically encoded syntactic properties of words in parallel, which makes it possible to characterize the peculiar syntactic properties of fake modification constructions.

Appendices

The definitions of the rules listed below but IDENTITY FUNCTOR INSERTION are from Kempson et al. (Reference Kempson, Meyer-Viol and Gabbay2001) and Cann et al. (Reference Cann, Kempson and Marten2005).

Table 1: INTRODUCTION

Table 2: PREDICTION

Table 3: ELIMINATION

Table 4: COMPLETION

Table 5: LINK ADJUNCTION

Table 6: LINK ANTICIPATION

Table 7: LINK COMPLETION

Table 8: LINK EVALUATION

Table 9: LOCAL *ADJUNCTION

Table 10: *ADJUNCTION

Table 11: IDENTITY FUNCTOR INSERTION