1. Introduction

Yoruba is a West Benue-Congo language with the largest concentration of its speakers in South-Western Nigeria. It has three tones, namely, High (H), Mid (M), and Low (L), plus downdrift and downstep. The phonology of Yoruba has been extensively studied (See for instance Oyelaran Reference Oyelaran1971, Akinlabi Reference Akinlabi1985, among others). Although the tone system has also enjoyed some scholarship (Hombert Reference Hombert1977, Courtenay Reference Courtenay1968, La Velle Reference La Velle1974, Connell and Ladd Reference Connell and Ladd1990, Laniran Reference Laniran1992, Bakare Reference Bakare and Owolabi1995, Laniran and Clement Reference Laniran and Clements2003, etc.), the nature of the downstep in the language remains unclear.Footnote 1

Downstep (DS) is a tonal phenomenon whereby a “H tone is realized at a lower pitch than a preceding H tone without any apparent conditioning factor” (Connell and Ladd Reference Connell and Ladd1990). It is however noteworthy that non-high tones can also be downstepped (Armstrong Reference Armstrong1968, Elugbe Reference Elugbe1985, Connell Reference Connell2001, Adeniyi and Elugbe Reference Adeniyi and Elugbe2018). It has been shown that in Yoruba, DS affects the M and H, but to different degrees (Courtenay Reference Courtenay1968, Connell and Ladd Reference Connell and Ladd1990: 6, Adeniyi Reference Adeniyi2009). The lowering effect of downstepped Mid (DSM) is clearly seen, while downstepped High (DSH) appears as a rising tone, which does not rise as high as a normal H.Footnote 2 Since this form of DSH also triggers terracing, it is regarded as a case of DSFootnote 3 (See Adeniyi Reference Adeniyi2009, Reference Adeniyi, Ndimele, Mustapha and Hafizu2013).

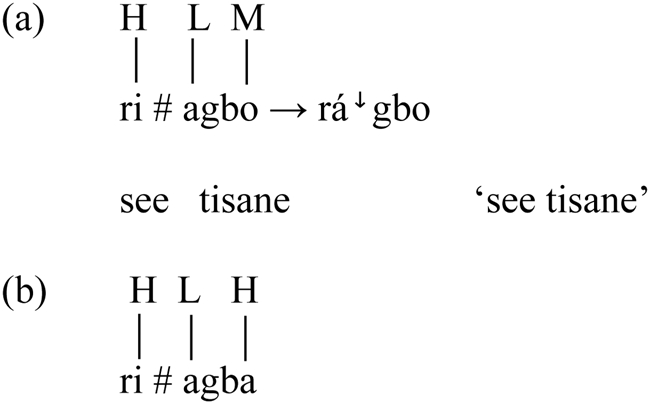

Downstep in Yoruba is highly restricted; it occurs only after H. Specifically, DS only arises in Yoruba in H#L-H or H#L-M sequences where vowels bearing H and L form a sequence across word boundaries (#). In the event that the vowel sequence gets reduced through the elision of one of the vowels or through coalescence, it is L that gets delinked and the tone following the delinked L becomes downstepped if it is either M or H. This is because the delinked L continues to exist in the phonology and the DS is the evidence of this fact. This is illustrated in examples (1a–b) below.

(1) Environment for DS realisation in Yoruba

Although it is possible to have any of the other eight tonal combinations of H#H, H#M, M#H, M#M, M#L, L#H, L#M, and L#L across word boundaries in Yoruba, none of these satisfies the structural condition for DS.Footnote 4

Lexicalisation is a “process whereby concepts are encoded in the words of a language” (O'Grady et al. Reference O'Grady, Archibald and Katamba2011: 637). Beyond this, Hilpert (Reference Hilpert2019) asserts that lexicalisation transcends mere word formation, to include “a range of processes that follow the coinage of a new element”. This is where downstep fits into the lexicalisation processes in Yoruba. Words that are diachronically derived and containing non-decomposable DS have become parts of the basic Yoruba lexicon and are listed in Yoruba dictionaries. This is what is meant by lexicalisation of DS in this article.

The objective of this article is to show that DS is not just a synchronic reflection of a phonetic process in Yoruba; it has a far-reaching diachronic effect as well. It will therefore be shown that it is no longer the case that all utterances containing DS can be decomposed, and that there are many instances indicating its entrenchment in the Yoruba lexicon as well as its progress in this regard. By this it is meant that DS is no longer limited to phrases in Yoruba; it is now frequently attested inside lexical items.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows; section 2 outlines the methods of data collection and analysis, while the data is presented in two separate categories (lexicalised and lexicalising) in section 3. In section 4 the basic M and H in Yoruba are compared with lexicalised and lexicalising downstepped M (DSM) and downstepped H (DSH) respectively. The relation between DS, Assimilated low tone (ALT), and contour levelling are discussed in section 5, and the work is concluded in section 6.

2. Methodology

Data for this work were sourced in three different ways; first, lexical entries containing DS in the Yoruba dictionaries by the Church Missionary Society (Reference Society1913) and Abraham (Reference Abraham1958) were extracted. All the entries found were provisionally classified as containing lexicalised DS, or at least at an advanced stage of lexicalisation. This categorisation was based on the author's intuition as a native speaker of Yoruba and confirmatory perception of DS in observed utterances produced by native speakers in the course of the research. Secondly, derived words containing DS were gathered from daily conversations in the Yoruba speech community and on Yoruba-based radio programmes over a period of six months; and thirdly, personal names containing DS were gathered.

Selected data items so gathered were inserted within carrier phrases such that the identified words occurred sentence-medially and finally (See Appendix). It was also ensured that the words were not preceded by low tone in those phrases, to eliminate the effect of intonational downdrift. It was further ensured that, as much as possible, the words were not preceded by voiceless consonants in the carrier phrases. This is mainly to avoid a situation where there would be voiceless consonant-induced tone raising in one utterance and lowering in another, thereby yielding conflicting signals. Hombert (Reference Hombert1977) conducted an experiment to determine the perturbatory effects of the voicing of prevocalic stops on tone in Yoruba, using /k/ and /g/, and reports that “a shorter part of the vowel” is perturbed by either of voiced or voiceless stops (Hombert Reference Hombert1977: 178, Reference Hombert and Fromkin1978). However, with Hombert citing Hombert and Ladefoged (Reference Hombert and Ladefoged1976) and Meyers (Reference Meyers1976) to prove that velar stops have “a more important perturbatory effect” on fundamental frequency (F0), one is left to suspect that the perturbatory effects of non-velar consonants will be less obvious. That is exactly what was seen in the data used for the present study–the depressing effects of the voiced consonants used were minimal and had no telling effect on the interpretation of the pitch curves. In contrast, DS-specific studies have shown that voiceless consonants exert a neutralizing effect on DS (Adeniyi Reference Adeniyi2015; Adeniyi and Elugbe Reference Adeniyi and Elugbe2018). The carrier phrases were then presented to competent speakers of the language who were required to render them in Yoruba. This was done with 21 speakers (15 male and 6 female) drawn from five dialects namely, Ibadan (4), Ijebu (4), Ilorin (4), Onko (4), and Oyo (5), with overall average age being 56 Years. Recordings were done using the Zoom Hn1 digital audio recorder to facilitate pitch tracking, by which the possible terracing effect of DS could be ascertained. The recorded utterances were then acoustically examined for tone lowering and terracing, which are the most basic features of DS.

The main pitch tracks are from the Oyo dialect. After each point has been made based on the Oyo dialect, comparative pitch tracks comprising different dialects are presented as supporting evidence of DS lexicalisation. The comparative pitch tracks were generated by measuring F0 at definite points along its curve (four equidistant points for level tones, and six for contour and pre-DS tones). The F0 readings were then transferred to Excel spreadsheets, from which the comparative F0s were generated. It should also be noted that each pitch track represents the speech of one representative speaker; this is possible because speakers of each of the dialects studied show consistently similar pitch patterns.

Pitch lowering of at least 10 Hz is regarded as significant in this study. It has been shown that in three-tone languages, a lowering of 10 Hz is usually perceivable by native speakers and is thus convenient as a benchmark for DS lowering (Adeniyi Reference Adeniyi2015).

3. Data

In this section, data on DS in Yoruba are presented in two groups. First, lexical items whose derivational histories are lost are presented, followed by lexical items having available synchronic derivation patterns.

3.1 Lexicalised forms

There exist in Yoruba lexical items containing non-decomposable DS. By non-decomposable, it is meant that the items contain DS but that none of them can be readily broken down into the component words. In addition, these items have defined entries in Yoruba dictionaries. Items listed in examples (2a–d) are in this category; (2a–b) are names of vegetables that are traditional to Yorubaland, but the input words to those names can no longer be retrieved (either linguistically or by the native speakers).Footnote 5 Examples (2c–d) are apparently verb phrases that have undergone nominalisation in the language. This means the initial ì- in both words is a nominalizer. But beyond that, the components of the remainder (kéꜜde for 2c and díꜜje for 2d) do not lend themselves to straightforward synchronic decomposition. The fact that these derived items have entries in published Yoruba dictionaries and that competent speakers can no longer recover the input words is evidence of lexicalisation.

A pitch track of the item in example (2a) is presented in Figure 1. Notice that the DSM occurring word-finally is 19.2 Hz lower than the M occurring word-initially. This acoustically clear case of lowering confirms the perceptual impression of DS in these utterances. It should be noted that although data from the Oyo dialect has been used to demonstrate DS in these utterances, the phenomenon is attested across the other dialects of Yoruba.

Figure 1: pitch track of ewúꜜro ‘bitter leaf’

The question may be asked as to whether the pitch lowering in the items in (2a–d) is capable of triggering terracing. The pitch track (of a representative speaker of the Oyo dialect) in Figure 2 answers this question. Notice, first, that in Figure 2, the word gúꜜre ‘water leaf’ is inserted in a longer sequence ewé gúꜜre ni mo já ‘It is water leaf that I cut’ where the DSM on ꜜre is both preceded and followed by mid tones such that we can easily compare the F0 of DSM with those Ms preceding and following. Notice also that the F0 on ꜜre is 10.3 Hz lower than the utterance-initial M, and that the two Ms following the DSM are even lower. The terracing also reflects on the H: the final H (coming after a DSM) in the utterance is more than 20 Hz lower than the one preceding the DS. It should be noted further that the utterance ewé gúꜜre ni mo já ‘It is water leaf that I cut’ contains no low tone, which eliminates the chance of attributing the attested lowering to intonational downdrift.Footnote 6 Besides, declination, which is the other form of lowering that can be seen in utterances, is usually gradual; whereas the point of lowering in Figure 2 is sudden, suggesting that it is also not declination.Footnote 7 Specifically, Connell and Ladd (Reference Connell and Ladd1990) conducted an experiment to test the nature of declination in Yoruba and report that the rate is very low, especially “in the all-H and all-M sentences” (Connell and Ladd Reference Connell and Ladd1990: 10–11). Consequently, the progressive lowering and terracing seen in Figure 2 can only be said to result from DS. This further corroborates the finding that the DS attested in non-decomposable lexical items in Yoruba still exhibits the basic characteristics of classical DS.

Figure 2: Pitch track of ewé gúꜜre ni mo já ‘It is water leaf that I cut’ showing terracing

3.2 Forms in the process of lexicalisation

The Yoruba lexicon contains many derived words that have synchronically decomposable DS. Examples (3–6) contain samples of these. The derivation of each of the words in examples (3a–f) involves the fusion of different lexical items plus the addition of nominal morphemes. Examples (4a–d) contain verb phrases functioning as verbs, (5a–c) are numerals, (6a) contains a combination of two nouns while (6b) contains adjective plus noun. Unlike the case with examples (2a–d), each of the examples in (3–6) is shown to be decomposable, as the presented derivations show.

Acoustic evidence of DS lowering in two of these words is seen in Figures 3 and 4. In Figure 3, it is possible to compare DSM with M occurring earlier in the word, and this comparison shows a lowering of 17.6 Hz. Likewise, Figure 4 contains a H-DSH sequence, and the DSH is 36.4 Hz lower that the preceding H. Again, these sample words are from the Oyo dialect, but they represent what obtains in other dialects studied in this work.

Figure 3: Pitch track of ojúꜜbọ ‘shrine’

Figure 4: Pitch track of láꜜlá ‘dream (v)’

4. Comparing basic tones with downstep in lexicalised and lexicalising words

Figure 5 presents a comparative picture of decomposable DSM, non-decomposable DSM and basic M in the same tonal environment. This is done by inserting three words, olóꜜgo ‘glorious’, ewúꜜro ‘bitter leaf’ and ológe ‘fashionable’ within the same carrier phrase. The derivation of ológe where a medial M is deleted in an M-H-M-M sequence to arrive at M-H-M with no lowering effect is shown in example (7); whereas the derivation of olóꜜgo ‘glorious’ is in (3d) and that of ewúꜜro has been lost. Notice that for ológe (black arrow), there is no significant difference between the height of the pitch on the initial o and ge. But for olóꜜgo, the M on ꜜgo, which is downstepped, is significantly lower than the initial M (on o). The significant lowering is also clear in the M on ꜜro in ewúꜜro compared to the initial M (on e). The terracing effect of these instances of DSM in olóꜜgo and ewúꜜro compared with ológe is then seen in the sequence of successive Ms that follow the DSM in each case. Notice that there are four Ms following the DSM in each case, and each of the Ms is restricted within the range of the DSM (not realised above it). But in the case of ológe without DSM, the heights of all the Ms are quite similar. This shows that whereas DSM in both decomposable and non-decomposable words creates terracing effects, the basic M does not have such effect in similar contexts.

Figure 5: Terracing effect of decomposable and non-decomposable DSM, compared with steady height of basic Ms

The terracing of DSH is more clearly seen than DSM due to the degree of lowering involved. Figure 6 contains a minimal pair distinguishable only by DSH. Notice that whereas the H-H sequence in lálá (lá ‘lick’ ilá ‘okra’) ‘lick okra’ contains similar height throughout the entire utterance, the sequence in láꜜlá ‘dream’ presents a picture of significant lowering on the second syllable of láꜜlá, which is then followed by a sequence of Hs that are significantly lower than the initial H. Although it may appear as if successive Hs after the DSH are higher than it, they are all within the same range and are all significantly lower than the normal H level.

Figure 6: Basic H compared with DSH lowering and its terracing effect in Standard Yoruba (SY)

5. Downstep, Assimilated Low Tone, and contour tone levelling

Yoruba has been reported to have a tonal phenomenon known as Assimilated Low Tone (ALT) first discussed in Bamgbose (Reference Bamgbose1967:4–7). Bamgbose (Reference Bamgbose1967) argues that the floating L in the output of utterances such as in (8a) below continues to exert effects on following linked tones and proposed a dot (“.”) to be inserted in the position where the L was delinked (following the elision of its host vowel). This inserted dot, Bamgbose argues, is the ALT. The ALT is then the written indicator of the perceptual distinction between (8a) and (8b). Note that the lost tone in (8b) is M, which has been shown to not have any lowering effect.

(8)

(a) ó wá ìṣẹ́ → ó wá (ì)ṣẹ́ → ó wá.ṣẹ́ ‘He looked for poverty’

(b) ó wá iṣẹ́ → ó wá (i)ṣẹ́ → ó wáṣẹ́ ‘He looked for work’ (Bamgbose Reference Bamgbose1967:5)

Further works have expanded the idea of ALT to indicate that the effect of that floating L is actually bi-directional (Elugbe Reference Elugbe and Owolabi1995, Adeniyi Reference Adeniyi2009). The bi-directional ALT effect is summarised in (9a–b).

(9) Bi-directional ALT effects in Yoruba

(a) A sharp fall in the pitch of preceding H tone (general effect)

(b) A rise in the pitch of following tone (only in the case of DSH)Footnote 11

Specifically, Adeniyi (Reference Adeniyi2009) argued that ALT is a stage in the development of DS in Yoruba. This means that in each DS illustrated in examples (1–6) above, there is an ALT effect where (9a) is perceived in the case of DSM and (9a–b) is perceived in DSH. This is the peculiarity of DS in Yoruba, and it is the reason why DSH, particularly, has been erroneously referred to as ALT.

However, the cross-dialectal data studied for this work show that these ALT effects have disappeared in natural speech, leaving plain DSM and DSH.Footnote 12 For instance, Figure 7 contains cross-dialectal pitch tracks of ewúꜜro. Observe first that in Figure 7, it is only the Ibadan dialect (black arrow) that shows a slight fall (ALT) in the H on wú (which is the pre-DS tone), and this fall is not perceivable in the flow of speech. Notice also that the final tone, which is DSM, is significantly lower than the M on the initial syllable in the three dialects represented. This shows that the DS lowering is still present, but the ALT component has disappeared in the three dialects. Even in the Oyo dialect, which formed the input to Standard Yoruba (SY), ALT has disappeared in the flow of speech. This is indicated by the broken lines. In SY, as shown in Figure 5, the slight, non-perceptible rise-fall contour is seen in the pitch track of ewúꜜro ‘bitter leaf’.

Figure 7: Comparative pitch track of ewúꜜro ‘bitter leaf’ showing lowering but no ALT

The second ALT effect is a rise in the pitch of a following tone, if that tone is H. This is essentially because H is realised as a rising tone after L;Footnote 13 this implies that even if the L is delinked before H, it is still active in the phonology, such that its spreading effect continues to be seen on the following linked H. It was shown in Figure 7 that the fall in the preceding H has either completely disappeared or has lost its acuteness in the case of DSM. This pattern is also evident in Figure 8. Notice in Figure 8, that rather than a rise, as ALT requires, DSH either falls (which is the converse) or is relatively steady in the three utterances represented. This is a piece of evidence that the ALT-rising effect has disappeared in natural speech. Also, none of the three dialects represented in Figure 8 has the ALT-fall on the pre-DSH tone. This disappearance of pre-DSH fall is also clearly seen in the SY data in Figure 6.

Figure 8: Comparative pitch tracks of abọ́ꜜdí, ‘bottom part (meat)’ báꜜyí ‘like this, now’ and rẹ́ꜜrín ‘laugh’ showing no rise in DSH across Oyo, Ibadan, and Ijebu dialects

The examples in Figure 8 are in word-final position, but the pattern is the same in medial position (Figure 9). Notice in Figure 9, which is a longer utterance, that all the four dialects realised the DSH –ꜜdá – either with a slight fall or as a level tone. The DSH is then followed by the ceiling effect typical of terracing. This was also seen in the example in Figure 6. This progression from ALT to full DSH is not out of place, since it is common for phonological change to be executed in stages (Burhanuddin et al. Reference Burhanuddin, Sumarlam and Mahsun2019).

Figure 9: Comparative pitch tracks of bẹ́lẹ́ꜜdá bá gbémi ga ‘If the creator lifts me up’ showing terracing, but no rise in DSH across Oyo, Ibadan, Onko and Ijebu dialectsFootnote 14

It is noteworthy that the levelling of the rising tone in a DSH situation is to a range significantly lower than H and closer to L. This is similar to what happens in Ebira, a related three-tone West Benue-Congo language in which both DSM and DSH are lowered to the same level within the range of L (Adeniyi Reference Adeniyi2017: 6). Progression to this state of total DSH in Yoruba may be said to involve first tone spreading (of L to a following H), then H-lowering (by which the rising H is considerably hampered), followed by L-delinking, and finally by tone levelling.

6. Conclusion

This article has pursued two objectives; first, the demonstration that DS has become an integral part of the Yoruba lexicon, and second, to show that ALT, which has long been held as a surface indicator of floating L in Yoruba, is currently being lost. Basic lexical items containing DS with lost derivational history, but with every expected characteristic of DS were shown to exist in Yoruba. It was then shown that many derived words containing DS are in the process of lexicalisation. This suggests that in spite of the restricted distribution of this DS phenomenon, it continues to evolve.

Since the DS phenomenon was first reported in Yoruba, reports have always revolved around ALT being its key distinguishing characteristic. In fact, following Bamgbose (Reference Bamgbose1967), ALT took attention from DS as scholars then focused on the search for ALT in other related three-tone systems of West Benue-Congo (see Hyman and Magaji Reference Hyman and Magaji1970 and Elugbe Reference Elugbe and Owolabi1995, for example). However, Adeniyi (Reference Adeniyi2009) showed that since ALT does not completely overshadow the other characteristics of DS in Yoruba, it may be that ALT is a stage in the process of the development of DS in the language. It has been shown here, with cross-dialectal as well as acoustic evidence, that Yoruba is indeed developing DS via ALT, and that the developmental stage of ALT is giving way to more classical-like DS.

APPENDIX: THE DATA