INTRODUCTION

Acute flank pain from suspected urolithiasis is a common presenting complaint in the emergency department (ED). In addition to renal colic, these patients can present with nausea, vomiting, fever, hematuria, dysuria, and urgency. Computed tomography (CT) has traditionally been the standard imaging modality used to diagnose obstructive kidney stones. However, concerns regarding radiation exposure and time delays, combined with increased training of emergency physicians, have led to the adoption of point-of-care ultrasound (PoCUS) as part of the diagnostic algorithm and risk stratification of acute flank pain.Reference Rosen, Brown and Sagarin 1

One such clinical pathway describes a PoCUS-first evaluation for the presence of hydronephrosis, a common secondary sign for obstructive urolithiasis (see Figure 18b in Cox et al. for more details).Reference Cox, MacDonald, Henneberry and Atkinson 2 If hydronephrosis is not seen initially on PoCUS, the patient is given a fluid bolus and the kidneys are rescanned. If hydronephrosis is not visualized but the patient continues to exhibit symptoms suggestive of renal colic, a clinically significant obstruction cannot be ruled out; however, other etiologies should also be considered. If PoCUS is positive for unilateral hydronephrosis, patients are further imaged with a kidneys, ureters, and bladder (KUB) X-ray. CT imaging and/or a urology consultation is recommended for patients with a stone>5 mm identified on KUB X-ray, or any suspected renal stone with persistent pain, elevated creatinine, or clinical signs of infection, regardless of the KUB findings.

CASE

A previously healthy, 29-year-old female presented to the ED with sudden onset right-sided flank pain beginning 3 hours earlier. The patient described the pain as severe (9/10), sharp, and colicky, with concurrent nausea and vomiting, dysuria and hematuria, but no anuria at any point. A past medical history was significant for previous kidney stones, most recently in 2015, requiring ureteric stents and lithotripsy. She noted that her symptoms upon presentation were similar but more severe compared to those she had experienced in the past with renal colic. Her medications included quetiapine, clomipramine, and minocycline.

On exam, the patient was afebrile, with a heart rate of 123 beats/min., respiratory rate of 16 breaths/min., and blood pressure of 160/118. Her abdomen was soft with no tenderness or guarding. A genitourinary exam revealed right flank tenderness with no left-sided findings. Respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurologic exams were normal.

In the ED, the patient was given ketorolac 30 mg intravenously (IV), ondansetron 4 mg IV, and morphine 5 mg IV. The patient was also given 1 L bolus IV to enhance visualization of hydronephrosis on PoCUS if present.

Bloodwork included a complete blood count (CBC), electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), creatinine, and glucose, all of which were normal. Point-of-care Beta hCG was negative. Point-of-care urinalysis was positive for the presence of protein, ketones, bilirubin, and blood.

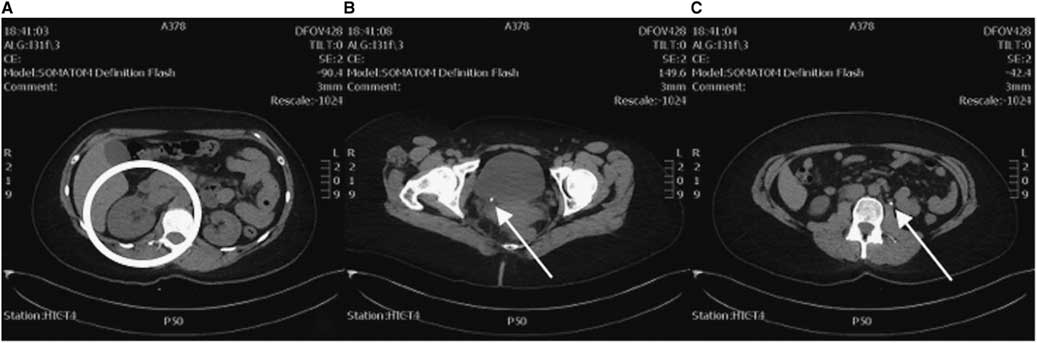

PoCUS revealed right-sided hydronephrosis (Figure 1). Left kidney, bladder, and aorta were all normal. KUB did not reveal calculi in the renal pelvis, ureter, or bladder, but radiology noted that overlying bowel gas and stool obscured a definitive assessment.

Figure 1 Renal imaging with PoCUS. A) Right kidney showing hydronephrosis. B) Left kidney normal comparison.

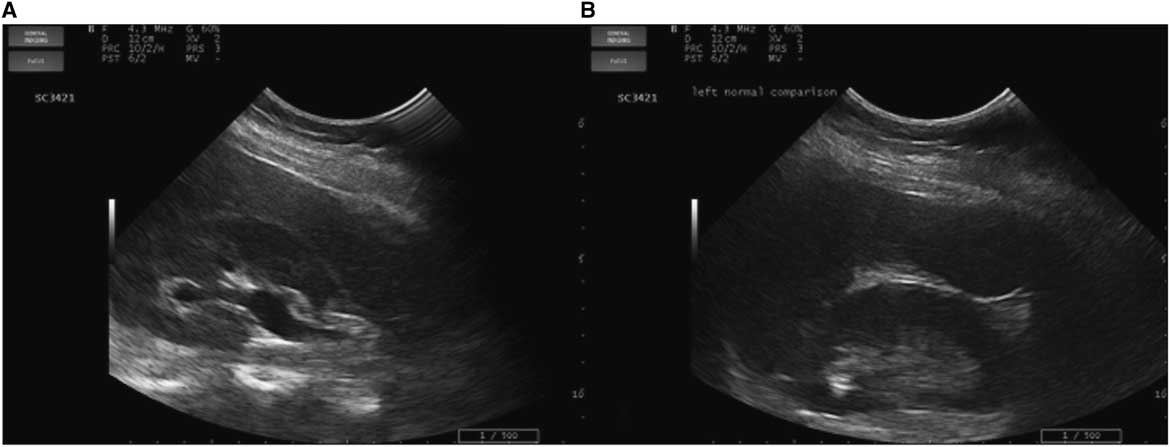

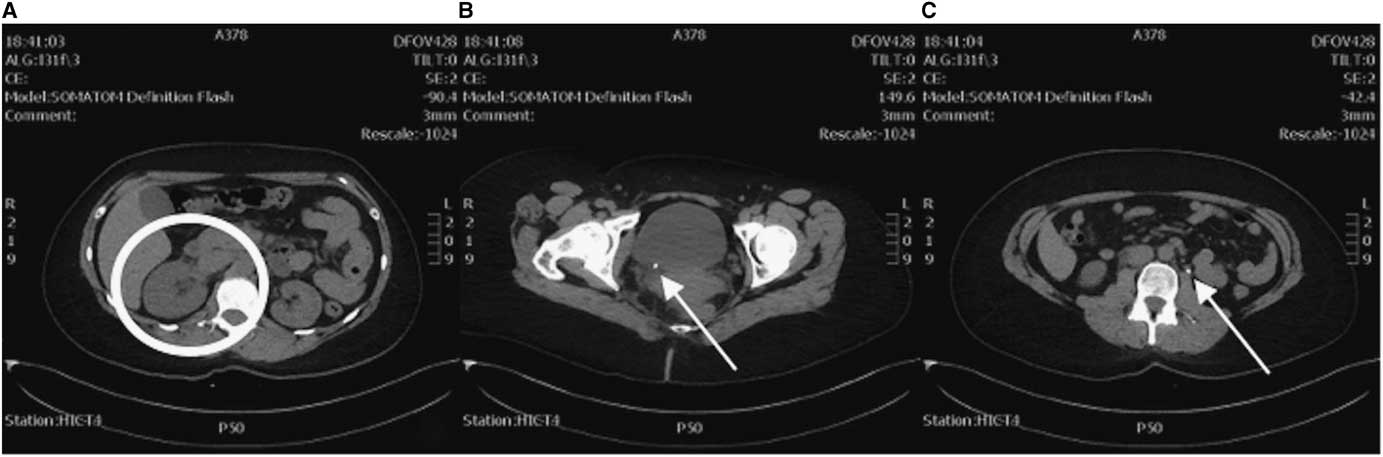

As the clinical course (demonstrated by intractable flank pain) failed to improve over 5 hours with symptomatic therapy and the diagnosis of renal colic yet to be confirmed, an abdominal and pelvic CT was ordered. This study revealed a small 5-mm distal obstructing ureteric calculus at the right vesicoureteric junction causing proximal moderate hydroureteronephrosis (Figure 2). Coincidentally, the CT also revealed another 5-mm left proximal ureteric calculus at approximately the level of the L3 vertebra causing mild ipsilateral proximal hydroureter.

Figure 2 CT axial views. A) Enlarged right kidney indicative of hydronephrosis (circle) compared to the left. B) A 5-mm right distal ureteric calculus at the right vesicoureteric junction (arrow). C) A 5-mm left proximal ureteric calculus (arrow).

With visualization of the ureteric stones, the etiology of the renal colic was confirmed. The patient’s pain was finally adequately controlled, and an urgent follow-up with urology for coordination of an outpatient stent placement was arranged. Urology followed the patient as an outpatient, and 2 weeks later she underwent a bilateral uteroscopy, at which time her right-sided pain had resolved but left-sided pain was now present. The uteroscopy revealed that both the right and left ureteric stones had passed. Four stones in the left renal calices were identified, fragmented with laser lithotripsy, and removed. She then received bilateral ureteric stents.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of unilateral ureteric obstruction secondary to a stone is around 20%; however, a presentation of bilateral obstructing calculi is uncommon.Reference Hou, Bushinsky and Wish 3 - Reference Stone, Knutson and Kang 5 We have presented, to the best of our knowledge, the first case in which a patient presenting with acute unilateral flank pain demonstrated unilateral nephrolithiasis on PoCUS, but bilateral ureteric stones on CT. Right hydronephrosis on a PoCUS exam correctly predicted the presence of an obstructing stone; however, the absence of left hydronephrosis on PoCUS was a false negative study compared to CT, the gold standard. Fortunately, for our patient, the persistent severity of her symptoms led to subsequent imaging and diagnosis. This avoided the potential pitfall of acute renal failure, a known complication of bilateral obstructive uropathy.

There are a number of factors that may have accounted for our patient’s left ureteric calculus not being identified prior to the CT. Firstly, the patient’s symptoms, primarily the presence of right-sided flank pain and the absence of pain on the left, clinically indicated unilateral pathology. Distraction from a painful source has been suggested to confound the physical exam in other clinical pathways, such as the NEXUS C-spine injury screening tool, so it is possible this occurred in our case. Secondly, the patient was scanned using PoCUS, a highly operator-dependent tool.Reference Herbst, Rosenberg and Daniels 6 This was unlikely to be an influential factor, however, because the scan was performed by a physician with CPoCUS Master Instructor credentials and more than 15 years of PoCUS experience. PoCUS is used to visualize hydronephrosis, a potential secondary consequence of obstructing calculi, and not the stones themselves. Ultrasound has a sensitivity and specificity for hydronephrosis ranging from 72% to 89% and 73% to 98%, respectively, but the degree of hydronephrosis can vary based on the size of the stone, hydration status, and the degree of obstruction.Reference Rosen, Brown and Sagarin 1 , Reference Mandavia, Aragona and Chan 7 , Reference Gaspari and Horst 8 It is possible that the left ureteric stone created an incomplete obstruction or that insufficient time had elapsed to produce hydronephrosis.

Several studies have examined the role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of renal colic. One study evaluating the validity of PoCUS in Noble and Brown’s algorithm for acute flank pain found that more than 50% of the patients in their study who presented to the ED with acute flank pain were safely discharged following a urinalysis and PoCUS without further investigations.Reference Kartal, Eray, Erdogru and Yilmaz 9 , Reference Noble and Brown 10 Moak et al. found that the sensitivity and specificity of PoCUS for hydronephrosis resulting from kidney stones were 76.3% and 59.4%, respectively, and increased to 90.0% and 63.9% for stones>5 mm.Reference Moak, Lyons and Lindsell 11 Most recently, Smith-Bindman et al. compared the effectiveness of three renal colic imaging pathways: PoCUS, diagnostic imaging ultrasound, and CT.Reference Smith-Bindman, Aubin and Bailitz 12 The randomized multicentre trial found no inter-group differences in high-risk diagnoses, serious adverse events, pain scores, or hospitalizations, and lower radiation exposure in the ultrasound groups compared to those in the CT pathway. The authors did, however, note that ultrasound-only patients were 40% more likely to return to the ED for subsequent imaging.

These studies indicate that a thorough history, urinalysis, and PoCUS may be sufficient for the diagnosis of kidney stones without CT imaging and potential exposure to radiation. However, the case that we have presented, along with the sensitivity of the renal PoCUS algorithm, demonstrates that this workup is not always adequate and that further imaging may be warranted. One possibility is diagnostic ultrasound performed by radiology, which is more sensitive than PoCUS.Reference Metzler, Smith-Bindman and Wang 13 However, in many centres including ours, a radiology performed ultrasound is only available at 0800 to 1600 hours, so this is not an option for patients presenting outside of this timeframe. KUB X-ray is also reasonable considering its lower radiation dose, 0.7 mSV compared to 10-12 mSV with CT and 1-3 mSV with low dose CT.Reference Gervaise, Gervaise-Henry and Pernin 14 However, it is less sensitive and may not exclude the need for further imaging, so CT is the best available imaging modality to confirm a diagnosis.

In most cases, the radiation exposure from one CT scan is unlikely to cause significant harm to a patient. For patients with recurrent ureteric stones, however, exposure to radiation must be considered. Our patient had a history of renal colic and had previously undergone three abdominal and pelvic CT scans. Avoiding another CT in this woman of child-bearing age should be preferred. Moreover, a recurrence of ureterolithiasis in patients like ours is common, thus potentially requiring additional CTs in the future.Reference Gervaise, Gervaise-Henry and Pernin 14 This is not an insignificant amount of radiation for a disease that does not typically produce complications or require surgical intervention. Newer low dose (1-3 mSV) renal CT protocols have been suggested to lessen the risk to the patient but are currently variable in their availability and radiation dose. In addition, waiting for a CT can result in a time delay to diagnosis, depending on its availability. With all of this in mind, the question of whether a patient with suspected renal stones requires formal imaging is an important opportunity for shared decision-making.

Probst et al. have proposed a framework for shared decision-making in the ED, which they argue is applicable in cases where 1) there is more than one reasonable medical option, 2) the patient is willing and able to make decisions, and 3) there is sufficient time.Reference Probst, Kanzaria and Schoenfeld 15 This framework can be applied to cases of renal colic. As we have discussed, there is growing evidence for avoiding CT scans in patients with suspected kidney stones by using different imaging pathways. A patient’s ability and willingness to engage in shared decision-making can be directly assessed in conversation, and time and patient safety are typically not issues because acute decompensations rarely develop from ureterolithiasis. Therefore, Box 1 outlines a potential script that we have developed based on the four steps of shared decision-making in Probst et al.’s study. This discussion compares urinalysis and ultrasound versus additional imaging with CT, the current gold standard. Emergency physicians can use and adapt this script for shared decision-making with patients with renal colic.

Box 1 A script for emergency physicians using shared decision-making with patients with renal colic and confirmed hydronephrosis on ultrasound

CONCLUSION

Shared decision-making is an important practice in the ED and can be used by emergency physicians using PoCUS algorithms for the evaluation of flank pain. PoCUS is a valuable tool with proven benefits, including reducing radiation exposure and potentially decreasing time to diagnosis, but has lower sensitivity and specificity compared to CT. The case we have presented is the first example in the literature of a patient with unilateral hydronephrosis on PoCUS, but bilateral stones on CT. This report provides cautionary information to clinicians, which should be considered when engaging in shared decision-making discussions with renal colic patients.

Competing interests: None declared.