No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 24 December 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Introduction

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Royal Historical Society 1962

References

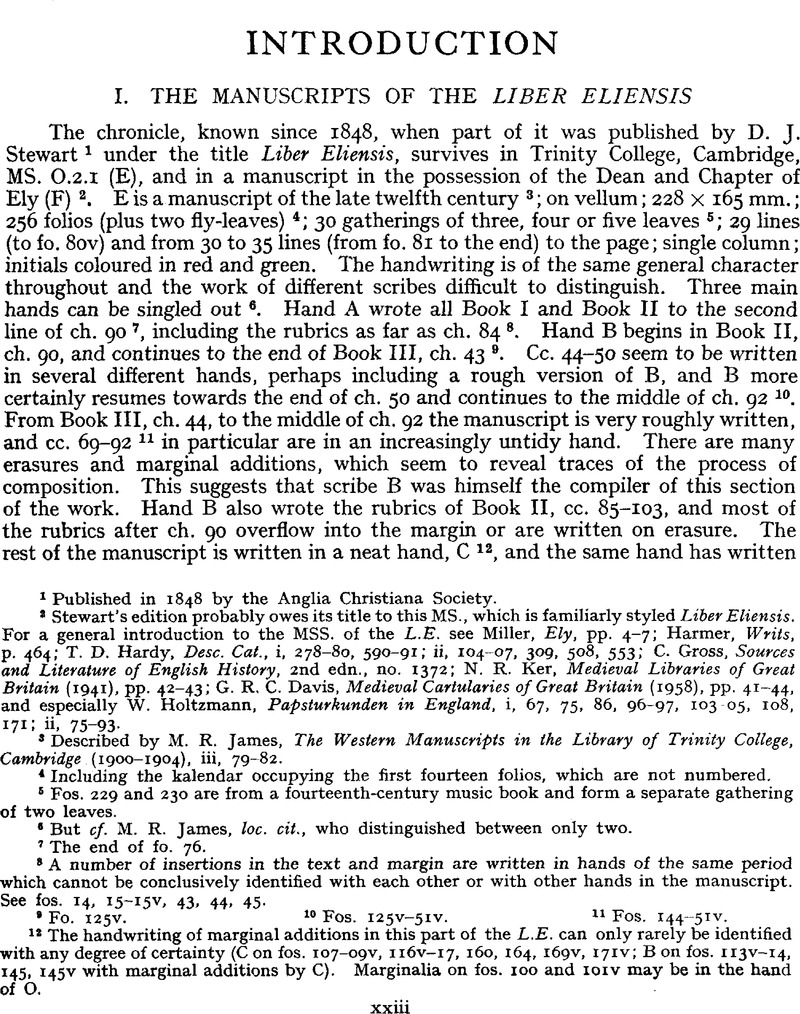

page xxiii note 1 Published in 1848 by the Anglia Christiana Society.

page xxiii note 2 Stewart's edition probably owes its title to this MS., which is familiarly styled Liber Eliensis. For a general introduction to the MSS. of the L.E. see Miller, Ely, pp. 4–7; Harmer, Writs, p. 464; T. D. Hardy, Desc. Cat., i, 278–80, 590–91; ii, 104–07, 309, 508, 553; C. Gross, Sources and Literature of English History, 2nd edn., no. 1372; Ker, N. R., Medieval Libraries of Great Britain (1941), pp. 42–43Google Scholar; Davis, G. R. C., Medieval Cartularies of Great Britain (1958), pp. 41–44Google Scholar, and especially W. Holtzmann, Papsturkunden in England, i, 67, 75, 86, 96–97, 103–05, 108, 171; ii, 75–93.

page xxiii note 3 Described by James, M. R., The Western Manuscripts in the Library of Trinity College, Cambridge (1900–1904), iii, 79–82Google Scholar.

page xxiii note 4 Including the kalendar occupying the first fourteen folios, which are not numbered.

page xxiii note 5 Fos. 229 and 230 are from a fourteenth-century music book and form a separate gathering of two leaves.

page xxiii note 6 But cf. M. R. James, loc. cit., who distinguished between only two.

page xxiii note 7 The end of fo. 76.

page xxiii note 8 A number of insertions in the text and margin are written in hands of the same period which cannot be conclusively identified with each other or with other hands in the manuscript. See fos. 14, 15–15v, 43, 44, 45.

page xxiii note 9 Fo. 125v.

page xxiii note 10 Fos. 125v–51v.

page xxiii note 11 Fos. 144–51v.

page xxiii note 12 The handwriting of marginal additions in this part of the L.E. can only rarely be identified with any degree of certainty (C on fos. 107–09v, 116v–17, 160, 164, 169v, 171v; B on fos. 113v–14, 145, 145v with marginal additions by C). Marginalia on fos. 100 and 101v may be in the hand of O.

page xxiv note 1 Printed by F. Wormald, Benedictine Kalendars after 1100, vol. ii. Cf. also B. Dickins, Leeds Studies in English and Kindred Languages, vi, p. 15.

page xxiv note 2 Both edited by N. E. S. A. Hamilton as part of his I.C.C. See infra, p. 426.

page xxiv note 3 The pencil foliation has been used in this edition and the duplicate folios are here numbered 78a and 84a. An older foliation excludes fo. 1 and numbers the remainder 1–189.

page xxiv note 4 This includes the index of chapter headings to Book II which was added later. The end of this index was written on a separate folio which was originally bound to precede fo. 39, but when the manuscript was re-bound in 1930 it was misplaced and is now fo. 36.

page xxiv note 5 E.g. on fos. 47 and 92.

page xxiv note 6 Infra, p. xxxviii.

page xxiv note 7 For a brief description see Historical Manuscripts Commission, 12th report, appendix, part ix, p. 393.

page xxiv note 8 Infra, pp. 1, 62, 63, 245. Although this would be a more correct title for the chronicle, the conventional title has been retained to avoid confusion.

page xxv note 1 The hand of O occurs also in a list of bishops and kings in Brit. Mus., MS. Cotton, Vespasian A.xix, fo. 51, which confirms the date. The hand, format and decoration also recalls Liber M, written about the same time. See infra, p. xli.

page xxv note 2 Cf. Holtzmann, Papsturkunden in England, i, 75; Hardy, Desc. Cat., ii, 36; Davis, Medieval Cartularies, p. 43. Space does not permit so detailed a description of these subsidiary MSS. mentioned here as that given for E, F and O. Further details can be found in my unpublished dissertation, Historia Eliensis, Book III (Cambridge University Library).

page xxv note 3 Infra, p. xliv.

page xxv note 4 Infra, p. 410.

page xxvi note 1 The relation of the contents of the Chronicon to the L.E. is best illustrated by the edition of H. Wharton in Anglia Sacra, i, 591–688. The chronological notes are taken from Book I (especially the De situ and ch. 41) and Book II (especially cc. 1–4 and 86) with additions from Bede, lib. i, and Florence. The genealogy corresponds largely with Book I, although the order is sometimes changed and new material added. There is no prologue to Books I and II. The history of the restoration of the abbey is abbreviated from Book II, cc. 2–4, 7, 37 and 50 and the rest is told in the form of a gesta abbatum: Abbots Brihtnoth (from cc. 6, 52–54, 56), Ælfsige (from cc. 57, 76–77, 79, 80), Leofwine (from ch. 80), Leofric (from cc. 80, 85–86, 94), Wulfric (from cc. 94, 97–98), Thurstan (from cc. 98, 101–03, 109, 111–13), Theodwin (from cc. 113, 115, 116, 114), Symeon (from cc. 118–19, 128, 130–37) and Richard (from cc. 140–43) with the second translation of Etheldreda (from cc. 144–48). Under the life of Bishop Hervey part of the prologue of Book III is retained, followed by excerpts from cc. 1–9, 17, 21, 25, 26, 28–36, 38, 41–43. The life of Nigel is abbreviated from cc. 44, 45, 47–54, 61, 64, 69, 73, 77–78, 82, 86, 89, 92, 96, 122–23, 137–41

page xxvi note 2 But cf. Wharton, op. cit., p. xlvi, who distinguished only three hands, ending at 1388, 1434 and 1486 respectively.

page xxvi note 3 Lambeth, MS. 448, fos. 78–91.

page xxvi note 4 This version of the Chronicon, apart from being bound up in the same volume, has no connection with the version of L.E., Book II and the cartulary mentioned supra, p. xxv.

page xxvi note 5 Now MS. Titus A.i, fos. 141–45, ending in 1435.

page xxvi note 6 A life of the bishops only, described by James, M. R., Descriptive Catalogue of the Manuscripts in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge (1912), ii, 56–58Google Scholar.

page xxvi note 7 A full Chronicon to the installation of John Morton (1479–86). The MS. is described in Historia Eliensis, Book III.

page xxvii note 1 A number of later transcripts have also been examined, but these add nothing to the tradition of the surviving MSS. (See especially Brit. Mus., MSS. Add. 6261, fos. 15–42v; 33491, fo. 28; Cotton Faustina E.iv, fo. 105; Claudius A.viii, fos. 119–23v; Vespasian B.xv; Vespasian A.xviii; Harley 258; Lansdowne 207 E.6; Lansdowne 320; Bodl., Rawlinson C.850, fos. 97–98v; Tanner 441; Tanner 118; also a fragment of Book II in a MS. belonging to Miss M. A. Arber. See also the valuable collections of James Bentham, C.U.L., Add. 2945, 2950, 2951, 2953, 2962 and of Bishop Wren, Ely Diocesan Registry, G.2.)

page xxvii note 2 T. Hearne, Leland's Collectanea, i, pt. ii, pp. 588 ff.

page xxvii note 3 P. 87.

page xxvii note 4 Anglia Sacra, i, 591–688. His marginal references to Cottonian i and Cottonian ii are to Titus A.i and Nero A.xv/xvi. He also knew C.C.C., 287 and excerpted sections from MSS. Cotton, Vespasian A.xix (pp. 678–81), Titus A.i (part i) (p. 682), and Domitian xv (p. xxxix) for the beginning of Book III, Book II, ch. 178 and the general prologue respectively.

page xxvii note 5 Vol. ii, 707 ff.; from MS. Cotton, Domitian xv.

page xxvii note 6 The Bollandist edition was based on a transcript owned by the college at Douai (and used also by Mabillon). This was copied later for Bolland and collated with the original in the Cotton Library (which must be Domitian xv). This collated transcript, no longer complete, survives as Vol. I of Phillipps MS. 8174 olim Heber, which was presented to Ely by Canon V. H. Stanton in 1897 and is now in the possession of the Dean and Chapter. Vol. II of this MS. gives extracts from Titus A.i. It is not clear whether this volume was copied from a transcript kept at Douai or directly from Titus A.i. See Bollandist Acta Sanctorum (1st edn.) Junii, iv, 489 ff.

page xxvii note 7 And other extracts; see supra, p. xxvi, n. 1.

page xxvii note 8 Pp. 463 ff.

page xxvii note 9 Printed from his MS., which is now at Trinity College, Cambridge, O.2.41, from which he also printed seven Anglo-Saxon charters and the privilege of Pope Victor II (Book II, cc. 5, 9, 58, 77, 82, 92, 93, 95).

page xxvii note 10 Infra, p. xxxiv.

page xxvii note 11 Omitting cc. 53, 55, 69 and 70.

page xxvii note 12 The transcript used to be P.R.O. Transcripts 31/5, no. 75, but it was sent to the secretary of the Anglia Christiana Society and not returned.

page xxvii note 13 Papsturkunden in England, ii. Detailed references are given in the footnotes to the text. He also prints the index of chapter headings of Book III with references to another printed edition of it (Stubbs, C. W., Historical Memorials of Ely Cathedral, 1897Google Scholar).

page xxviii note 1 E.g. Bede, i, 15; ii, 15; iii, 7–8; iii, 18; iv, 3 and especially iv, (17) 19. The Eccl. Hist, is sometimes expressly cited under such titles as Anglorum historia (infra, Book I, ch. 8) and once strangely as liber sermonum Bede presbiteri (ch. 9).

page xxviii note 2 Ed. T. Mommsen, M.G.H., Chron. Min., iii, 314–15 (infra, Book I, ch. 34).

page xxviii note 3 Infra, Book I, cc. 2 and 8.

page xxviii note 4 Infra, Book II, cc. 86, 100–01, 140. For comments on this MS. see Memorials of St Edmund's Abbey, ed. T. Arnold (R.S., 1890), i, pp. viii, 340 f., and J. R. H. Weaver, The Chronicle of John of Worcester, Anecdota Oxoniensia, Medieval and Modern Series, Part xiii (1908).

page xxviii note 5 Infra, Book I, ch. 15; Book II, ch. 80. The A.S.C. used must have been a version of the E type. The 673 entry is in all versions, but Abbot Leofwin is mentioned only in E and F. Another reference, to the A.S.C. s.a. 798 (in Book II, ch. 147), must be to an addition in F, which alone has this information, but it does not indicate the source used by the L.E., since ch. 147 is part of a passage borrowed from a Life of St Wihtburga. Cf. infra, p. xxxvii.

page xxviii note 6 Book II, ch. 90. Cf. Encomium Emmae Reginae, ed. A. Campbell (Camden third series, vol. lxxii), pp. lxv ff.

page xxviii note 7 Infra, Book II, cc. 107, 110, 111.

page xxviii note 8 Ibid., cc. 107, 109, 110.

page xxviii note 9 See Gesta Guillelmi, pp. xv and 270.

page xxviii note 10 Hist. Eccl., ii, 197, 196, 184, 197–98.

page xxviii note 11 See infra, p. 286.

page xxviii note 12 See notes to Book II, ch. 107, and cf. Gesta Guillelmi, p. 200 and Orderic Vitalis, Hist. Eccl., ii, 149.

page xxviii note 13 Hist. Eccl., ii, 217–18; Gesta Guillelmi, p. xv.

page xxix note 1 Infra, Book I, ch. 7.

page xxix note 2 Ibid., ch. 8.

page xxix note 3 Ibid., prologue and cc. 8–10.

page xxix note 4 Ibid., De situ, ch. 8; also cited in the general prologue and Book II, ch. 105.

page xxix note 5 Infra, Book II, proem and cc. 53, 72. The Life by Adelard (Memorials of St Dunstan, ed. W. Stubbs, R.S., 1874, pp. 53–68) may also have been used. See infra, Book I, ch. 42; Book II, cc. 53, 72.

page xxix note 6 Infra, Book II, ch. 71.

page xxix note 7 Infra, Book I, ch. 37.

page xxix note 8 Infra, Book I, ch. 6.

page xxix note 9 Ibid., ch. 2.

page xxix note 10 Ibid., prologue.

page xxix note 11 Ibid., ch. 36.

page xxix note 12 Ibid., ch. 6.

page xxix note 13 Infra, Book II, ch. 62.

page xxix note 14 Infra, Book I, ch. 42.

page xxix note 15 ‘ cum plurimo comitatu ducum et procerum, quos enumerare honerosum est, in cronica vero describuntur ’ (Book I, ch. 39).

page xxix note 16 Ibid.

page xxix note 17 Infra, Book II, ch. 79.

page xxix note 18 Infra, Book III, ch. 143.

page xxix note 19 Ibid., ch. 25.

page xxix note 20 In ch. 46 Stephen's actions immediately after his accession are described in words which Florence (i, 224–25) uses for the reign of Harold (also used in L.E., Book II, ch. 101). Ch. 72 describes the state of England before the battle of Lincoln (1141) in words taken from the Florence annal for 1136 (ii, 96). This cannot be derived from Bodl., MS. 297 which ends in 1131. But it occurs in other chronicles associated with Bury—Brit. Mus., MSS. Harley 447 and 3775 s.a. 1136.

page xxix note 21 E.g. in a chapter, not in E or F, added after Book II, ch. 54. See infra, p. 126.

page xxix note 22 E.g. in Book II, ch. 79.

page xxix note 23 Infra, p. 126, n. 2.

page xxx note 1 O, fos. 109v–112v, 115v, 118–24, 161. These notes concern the consecration of Geoffrey Ridel (Diceto, i, 391–95), the death of Henry II (Diceto, ii, 65), the death of Geoffrey Ridel (Diceto, ii, 68), the election of William Longchamp (Diceto, ii, 69, 75), the election of Eustace (Diceto, ii, 159), the death of Richard I (Diceto, ii, 166; but O has a different set of verses), and the accession of John (Diceto, ii, 166).

page xxx note 2 For the accession of John (Howden, iv, 87–88) and some passages concerning Richard's crusade and captivity (Howden, iii, 112, 182, 185).

page xxx note 3 See the introduction to The Historical Collections of Walter of Coventry, ed. W. Stubbs (R.S., 1872). The shared passages concern the end of the interdict and the coronation of Henry III (Walter of Coventry, ii, 216–17, 225–26, 229–30 and 244).

page xxx note 4 Infra, p. 6.

page xxx note 5 Cc. 1–2.

page xxx note 6 Ch. 3, beginning ‘ Beata et gloriosa regina Ætheldretha …’

page xxx note 7 Cc. 26–31.

page xxx note 8 Ch. 32.

page xxx note 9 Cc. 39–49.

page xxx note 10 Infra, Book III, ch. 33.

page xxx note 11 They are included also in Book III as cc. 33–36.

page xxx note 12 He refers to the miracles of Hervey's time as nostro tempore and prefaces the first of them with a eulogy on Henry I. Cf. C. W. Stubbs, Historical Memorials of Ely Cathedral, p. 66. The metrical version ends incomplete after the first of these miracles and the scribe of the MS. left a space in his index of chapter headings for the three remaining miracles. This suggests that this copy was made while Gregorius was still at work and therefore belongs to the reign of Henry I. Also one of the miracles of Bishop Nigel's time (Book III, ch. 60) is dated 1134–35 and this was presumably not yet available for copying into the Corpus book. The handwriting and the decorated initial at the beginning of the MS. would suit a date in the second quarter of the twelfth century. Cf. G. Zarnecki, The Early Sculpture of Ely Cathedral (1958), pp. 31 and 43, n. 20. The MS. is described in M. R. James, Desc. Cat. of the MSS. in the Library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, ii, 251–53.

page xxx note 13 See Analecta Bollandiana, xlvi, 86–88.

page xxxi note 1 These are indicated in the footnotes to the text infra.

page xxxi note 2 E.g. ch. 4.

page xxxi note 3 See notes to cc. 4, 10, 21, 26, 27, and 28.

page xxxi note 4 Ch. 15, which adds the construction from the Hebrew on which this interpretation rests.

page xxxi note 5 See notes to ch. 21.

page xxxi note 6 Other surviving Latin Lives of Etheldreda closely follow Bede, iv (17) 19. Cf. Hardy, Desc. Cat., i, 264, 282–84; Analecta Bollandiana, xvii, 67; xxix, 76; xlvii, 244; liv, 342; lvi, 336; also Cat. Cod. Hag. Lat., ii, 355. Only the Life in Brit. Mus., MS. Cotton, Tiberius D.III departs appreciably from the language of Bede and introduces some rhyming prose. But it shares no significant parallels with Dublin or Corpus.

page xxxii note 1 See ch. 49,‘ Hec breviter memorantes, in libro miraculorum beate virginis plene disseruntur’.

page xxxii note 2 Cc. 44–48.

page xxxii note 3 Ch. 41, and also in ch. 49.

page xxxii note 4 Ch. 42.

page xxxii note 5 At the point where the L.E. inserts the miracles, the Dublin/Corpus Book omits them, but refers to ‘ que prescripta sunt miracula ’.

page xxxii note 6 They are indicated in the footnotes to the text.

page xxxiii note 1 Cc. 44–47.

page xxxiii note 2 B is a manuscript of the thirteenth century or later and, even if we assume that the collection of miracles existed in an earlier manuscript version, which is likely, it cannot have been composed before 1174, as one of the miracles refers to Bishop Geoffrey Ridel (fo. 72, col. b). The collection also retains phrases which make sense only in the context of the L.E. (e.g. ‘ ut supra memoravimus’, Book II, ch. 122; ‘ cuius iam supra meminimus’, Book III, ch. 138; Richard Fitz Neal, ‘ supermemoratus ’, Book III, ch. 138; Ranulf, ‘ memoratus’, Book III, ch. 47).

page xxxiii note 3 See notes to Book II, ch. 1.

page xxxiii note 4 See notes to Book II, ch. 3.

page xxxiii note 5 Book II, ch. 4.

page xxxiv note 1 See notes to Book I, cc. 18, 32, 35. The passages there noted occur also in a Life of Sexburga in Trinity College, Cambridge, MS. O.2.1 to which they intrinsically belong. As this life is a copy appended to the manuscript of which the L.E. forms the first part, the compiler must have used it in an earlier manuscript version. The collections of Lives in Brit. Mus., MS. Cotton, Caligula, A.viii, and C.C.C., MS. 393 contain only a set of lectiones on Sexburga which have not been used.

page xxxiv note 2 See ch. 36, where a parallel is noted with the Life in Trinity, MS. O.2.1, which is related to, but not identical with, the lectiones in MS. Cotton, Caligula A.viii, and Corpus, 393.

page xxxiv note 3 Except cc. 5, 6, 9, 16, 28, 29, part of 39, 40.

page xxxiv note 4 Described in detail in Historia Eliensis, Book III.

page xxxiv note 5 Described by James, M. R., The Western MSS. in the Library of Trinity College, Cambridge, iii, 145–46Google Scholar.

page xxxiv note 6 Infra, p. xl.

page xxxiv note 7 A and C share an omission due to a scribal error which is made good in E and F. The latter must therefore derive from an earlier manuscript version of the Libellus, while A, which has two omissions not in C (infra, Book II, cc. 18, 32), is probably a copy of C.

page xxxiv note 8 Infra, Appendix A, p. 395.

page xxxiv note 9 Infra, Book II, proem. Cf. also Book III, cc. 119 and 120, where it is referred to as ‘ liber terrarum quern librum sancti Æðelwoldi nominant ’. Cf. also Whitelock, D., ‘The Conversion of the Eastern Danelaw’, Saga-Book of the Viking Society, xii (1941), p. 160Google Scholar. For further comments see Professor Whitelock's Foreword, supra, pp. ix–xviii, and also infra, p. li.

page xxxiv note 10 Infra, Book II, ch. 107.

page xxxiv note 11 Printed by C. T. Martin as an appendix to Gaimar's Lestorie des Engles (ed. Sir T. D. Hardy and C. T. Martin, R.S., 1888, ii, 339–404) under the title Gesta Herwardi incliti exulis et militis. References will be made to this edition. For a notice of the earlier editions by T. Wright and F. Michel see ibid., p. xlvii, and for a later edition see De Gestis Herwardi Saxonis, ed. S. H. Miller, Fenland Notes and Queries, iii (1895–97). Cf. Hardy, Desc. Cat., ii, 22; F. Liebermann, Über Ostenglische Geschichtsquellen, p. 14; H. W. C. Davis, England under the Normans and Angevins (13th edn., 1949), App. III, pp. 525–26; Freeman, Norman Conquest, iv, note OO, pp. 804–12.

page xxxv note 1 Gesta Herwardi, p. 339.

page xxxv note 2 Book II, cc. 104–07.

page xxxv note 3 See notes to cc. 104 and 105. The common passages in cc. 106 and 107 have not been noted for lack of space.

page xxxv note 4 Gesta Herwardi, pp. 375–76.

page xxxv note 5 Ibid., p. 381.

page xxxv note 6 Ibid., p. 383.

page xxxv note 7 Ibid., pp. 387–88.

page xxxv note 8 Ibid., p. 390.

page xxxv note 9 E.g. Deda's report on the resources of the island and on the privileges of the abbey. Other phrases are introduced from William of Poitiers in ch. 107.

page xxxv note 10 In Deda's report (ch. 105), Gesta Herwardi, p. 379.

page xxxv note 11 Ibid., in William of Warenne's reply.

page xxxv note 12 In its account of the skirmish at Reach (ibid., pp. 382–84), the fight in the king's kitchen (pp. 385–88), and the last battle (pp. 388–90).

page xxxv note 13 P. 377.

page xxxv note 14 Ch. 104.

page xxxv note 15 P. 377.

page xxxv note 16 Ch. 104.

page xxxv note 17 Pp. 380–81.

page xxxv note 18 Ch. 105.

page xxxv note 19 P. 381.

page xxxv note 20 Ch. 105.

page xxxvi note 1 P. 381.

page xxxvi note 2 Ch. 105. There are similar examples in ch. 106 (Gesta, pp. 382, 384).

page xxxvi note 3 Gesta Herwardi, p. 340.

page xxxvi note 4 He describes his first attempt as ‘ crudam materiam … minus dialecticis et rhetoricis enigmatibus compositam et ornatam ’ (ibid., p. 340).

page xxxvi note 5 Ibid., pp. 339–40.

page xxxvi note 6 The point is made by Liebermann, loc. cit.

page xxxvi note 7 See infra, p. xlviii.

page xxxvi note 8 If the vestra dilectio, addressed in the preface, is—as is likely—a bishop of Ely, the Gesta were probably written before 1131, since the addressee also is stated to have seen two of Hereward's knights and it is improbable that they, maimed as they were, lived long enough to meet Bishop Nigel.

page xxxvi note 9 Fos. 33 ff.

page xxxvii note 1 Corpus gives the names of those who inspected Wihtburga's body at a point corresponding to the middle of Book II, ch. 147, where the L.E. says quos supra memoravimus, having already named them in ch. 144. Evidently the source used by the L.E. had the names in the same place as Corpus.

page xxxvii note 2 Also the chronological calculations in ch. 147 ‘ De huius quippe … ostensa est corpore ’ are given later in Corpus, as the last passage of the Life (cf. infra, ch. 148). This position is more appropriate and there is no reason why the L.E. should have advanced it. The most likely explanation is that it was a marginal addition in the source used by both.

page xxxvii note 3 Fos. 236v–240v. The Trinity and Corpus Lives are for the most part identical. Corpus cannot be derived from Trinity, since a number of phrases, which it does not share with Trinity, fit too naturally into the stylistic pattern of the whole to be regarded as later additions. Also Corpus makes no use of much historical and genealogical information which Trinity adds to the prologue. These additions in Trinity are made in a simple prose quite distinct from the rhyming prose of the matter shared with Corpus; yet Trinity cannot be based on Corpus, since it ends with a miracle which occurs earlier in Corpus and it is Corpus, not Trinity, which acknowledges a change of order (‘ His e diverso tempore assimilatis et ex similitudine annexis, ad superiora proposita reditus detur associabilis ’). Corpus therefore must have worked from a source which placed the miracle in the same position as it occupies in Trinity, and it is this source, of which no manuscript version has survived, to which both owe their common stock. The Trinity Life in its present state does not include the two translations, but it ends abruptly—the last few lines being added in a later hand—and they may well have been part of its source. Another collection of Wihtburga's miracles in Caligula A.viii bears no close relationship to either Trinity or Corpus and does not help to determine their common source.

page xxxvii note 4 Ed. C. Horstmann (1901), i, 36.

page xxxviii note 1 Vaughan, R., Matthew Paris (1958), p. 200Google Scholar.

page xxxviii note 2 Ibid., pp. 198–204.

page xxxviii note 3 Cf. Bentham, Ely, i, 85.

page xxxviii note 4 Cc. 62, 65, 71, 72, 75, 86, 87 and 99.

page xxxviii note 5 In every case, with the exception of Bishop Osmund, the date of death is given in a similar form. Each is said to have been translated inter alios (or some similar phrase) and the opening passage of the chapter about Wulfstan clearly was intended to introduce a narrative treating of them all (‘ primum eum in serie aliorum collocantes, quos subsequens narratio declarabit’—and this in ch. 87 when in the L.E. only the account of Osmund remains to be given). The compiler explains the change of sequence: ‘ Horum primus est in ordine vir optimus Wlstanus, licet aliquorum, exigenti narrationis serie, supra meminimus ’.

page xxxix note 1 ‘ Ad hoc monacus Ricardus auctor huius operis et hanc historiam stilo commendavit, causam negotiumque pro ecclesia suscipiens … de arbitrio domini pape decidendum appellavit ’ (ch. 96). See infra, p. xlvii.

page xxxix note 2 ‘ Pretermitto plurima que in opusculis fratris nostri historiarum studiosissimi deserti et eloquentissimi viri plenius referuntur ’ (ch. 44). ‘ Hec quidem latius scriberem, sed, quoniam in venerabilis iam dicti patris Ricardi opusculis plene inveniuntur, ad alia festinamus ’ (ch. 45).

page xxxix note 3 They are indicated in the footnotes to the text. The argument is more fully set out in ‘The Historia Eliensis as a Source for Twelfth-Century History’, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, xli (1959), pp. 311–16Google Scholar.

page xxxix note 4 E.g. ‘Itaque cara et preclara Eliensis metropolis luxit et elanguit, suo orbata presidio a iugo destituta solatio … et de more pro pastore in vigiliis, in ieiuniis …’ (ch. 44); ‘… cuius honestas totam curiam illustrabat, potestas regebat, largitas extollebat …’ (ibid.); ‘… verba pretendit … monita adiungit … ferre commonuit … devote spopondit …’ (ch. 45); ‘… vir impius, inventor sceleris … multipliciter afflixit … gravamina intulit … contumeliis lacessivit … rapere non timuit … ’ (ch. 96). If Richard is taken to be the compiler of the L.E. itself as well as the author of these opuscula, the evidence from style cannot of course be admitted to help determine the contents of the opuscula. See infra, p. xlvii.

page xxxix note 5 His complaints at the curia covered a wide range (cc. 102, 101) and a digest of them might well have been included in the Stetchworth historia.

page xxxix note 6 In B (Book of Miracles) these four chapters are given as one continuous story, but, as this is clearly derived from a source which had previously mentioned Nigel's clerk Ranulf, it is probably taken from the L.E. The only other narrative sources taken into Book III are the miracle stories in cc. 33, 35 and 43. The most interesting of these is ch. 33, concerning the liberation of Bricstan, which is adapted from a story composed by Abbot Warin of St Evrout, another version of which has found its way into Orderic Vitalis, Hist. Eccl., iii, 122–34. Like other miracle stories in Book III these probably belonged to a collection of miracles from which they were copied in approximately chronological order into the L.E.

page xl note 1 Book II, cc. 9, 39, 58, 72.

page xl note 2 Book III, ch. 53.

page xl note 3 Book II, ch. 39.

page xl note 4 Book II, cc. 5, 9, 39, 58, 82, 92, 93, 95, 116–17, 120–27, 136; Book III, cc. 2–7, 10–13, 15–16, 18–19, 26, 55, 54, 56, 65–67.

page xl note 5 Book III, ch. 55 precedes ch. 54.

page xl note 6 Cc. 28, 77, 114 and 139.

page xl note 7 Cc. 8, 14, 20–24 and 40, 49, 63.

page xl note 8 Except one letter of Archbishop Theobald in D. See infra, Book III, ch. 91.

page xl note 9 Cc. 68, 85, 79, 84, 80–81, 83 (end of the second hand in C), 95, 105 and part of 104 (end of C and change of hand in D); only in D, cc. 91 (followed by another version of this which is not in the L.E.), 90, 106, 134.

page xl note 10 See textual notes to e.g. Book II, cc. 117, 126, 127, 136 and Book III, cc. 79, 85. For omissions in D only see e.g. Book III, cc. 2, 6, 7, 13, 81, 83.

page xli note 1 This relationship between C, D and E matches the suggestion made by J. H. Round for the versions of the I.E. in the same manuscripts. Refuting the conclusions of N. E. S. A. Hamilton—who took the version in E to be derived from C—he held that the D version was an inferior copy of C and that E, which corrects C's inaccuracies, derived from a source held in common with C. Cf. Hamilton, I.C.C., pp. 97 ff. and xiii ff. and Round, Feudal England, pp. 124–25. They use the letters A for Tiberius A.vi (D), B for Trinity, O.2.41 (C), and C for Trinity O.2.1 (E). Cf. also G. R. C. Davis, Medieval Cartularies, pp. 42–44.

page xli note 2 It also lacks Book II, ch. 128 (added in the margin of F only) and Book III, ch. 133 (in the margin of E only). Book III, ch. 114 is entered twice. While the cartulary seems to have begun originally with Book II, ch. 116, four charters were later copied in to precede it (Book II, cc. 92, 93, 9. 39) and one was added at the end (Book II, ch. 77). It ends with fifteen documents, not in the L.E., mainly connected with the election of a successor to Bishop Nigel, three of which have been printed by R. Foreville, ‘ Lettres “ Extravagantes ” de Thomas Becket …’ (Mélanges d'histoire du Moyen Age dédiés à la mémoire de Louis Halphen, no. xxix, pp. 225–38).

page xli note 3 Book III, cc. 8, 14, 71, 75, 76. It also includes the inventory in Book II, ch. 114 (in the margin of E), but not that in Book II, ch. 139.

page xli note 4 Book III, cc. 49, 63, 70, 71, 75, 76, 87, 88, 114. These are followed in G by letters of Innocent II (Book III, cc. 54–55, 65–67, 56) after which the order of the L.E. is resumed, except that ch. 128 precedes ch. 127. Also Book III, ch. 8, precedes ch. 7.

page xli note 5 See textual notes to e.g. Book II, ch. 114; Book III, cc. 2, 5, 16, 18, 22, 23, 66, 71, 85, 98, 103, 106, 129, 140.

page xli note 6 See the concluding phrases of Book II, cc. 116 and 117, Book III, cc. 4 and 5. In Book II, ch. 136 G adds igitur and idem with E and F—words which do not belong to the charters and are omitted from C and D—and in several instances shares other readings with E and F against C and D (e.g. Book III, ch. 54).

page xli note 7 One error which clearly originated in E led to amendments in G and F. In E the last word on fo. 172 is Dei, the first on fo. 172v is legiis. G amends the latter to legibus, F (on erasure) to privilegiis (ch. 134). It is, however, possible that G preserves the original version. In Book III, ch. 85 F reads in aquis sicut solebant, where E and G omit sicut (E adding in quibus in the margin), and in ch. 14 G and E read scilicet which is omitted in F.

page xli note 8 Cc. 114, 139.

page xli note 9 See infra, p. xliv.

page xlii note 1 Cf. G. R. C. Davis, Medieval Cartularies, p. 43. The manuscript resembles O in handwriting and general appearance.

page xlii note 2 Book II, cc. 114, 138; Book III, cc. 8, 14, 32, 71, 75, 76.

page xlii note 3 Fos. 144–51v (Book III, from the end of ch. 68 to the middle of ch. 92). But the autograph may begin already earlier. See supra, p. xxiii.

page xlii note 4 This would explain the errors shared by E and F in Book III, cc. 15, 54, 56, 95, 134, 137, 138. F has several omissions and inferior readings which could be the result of careless copying (cc. 26, 35, 36, 60, 96, 116) or attempted correction (cc. 38, 43, 74, 121). For a variant which can probably be traced to an error in E see supra, p. xli.

page xlii note 5 It adds an excerpt from William of Poitiers in ch. 90 and also the cc. 69, 70, 138.

page xlii note 6 The strongest piece of evidence for E as the direct source of F is the inclusion of the word perrexit in the text of ch. 142. This occurs at the corresponding place on the line in E, but is part of the inset rubric. As this is written in red in E, F's error is unnatural, and it may be that E exactly reproduced the lay-out of an earlier recension with the rubric in the same shade of ink as the text.

page xlii note 7 E.g. in cc. 55, 66, 69, 85, 109, 111, 134.

page xlii note 8 E.g. in cc. 83, 104, 105, 106, 137. In ch. 78 E reads ornamentis, followed by ornatibus lined through: yet F reads ornatibus only.

page xlii note 9 It also wrote the rubrics to the text as far as Book II, ch. 84.

page xliii note 1 The rubric to ch. 108 was originally missing also from the index of F, as was that of ch. 109, and they were added in the margin. But this seems to be without significance, as the index in F was copied in after the completion of F Book II and as the additions are in the same hand as the rest of the folio on which they occur, presumably correcting an accidental omission by the scribe.

page xliii note 2 I.e. 73, 77, 80, 74, 75, 78, 79, 84, 85, 81, 82, 86–89, 83, 90.

page xliii note 3 The only exception is ch. 80, which ends with the election of Abbots Leofwine and Leofric in the reign of Cnut. But here too the chief time reference is the death of Abbot Ælfsige tempore regis Æthelredi, which would account for its insertion at this point.

page xliii note 4 For instance, if F did not work from E, the recension from which it did work must have had an abbreviated version of the Libellus like E. F gives the phrase ‘ Collectis igitur omnibus terris … habenturque ibi hyde lx ’ as the last sentence of both cc. 23 and 24. If F had been prepared from a Book II giving the Libellus in full, the sentence would have come only in ch. 24. E, however, omits the chapter of the Libellus, corresponding to ch. 24 in F, except for this last sentence which it appends to ch. 23 without a new rubric. Presumably the F version copied ch. 23 from an abbreviated version like E, then supplied ch. 24 in full from the Libellus and repeated its last sentence.

page xliv note 1 The cartulary in G gives Godfrey's inventory after ch. 117, which suggests that G was here following the archetype and not E. As it omits Ranulf's inventory altogether this suggests further that the archetype did not give this inventory in full in a form suitable for inclusion in a cartulary. The omission of the same inventory from O must have a different explanation, as O gives cc. 113–15 in the order of F. As, like E, O also omits ch. 138, it may have been following F at one point and E at the other. Cf. infra, p. xliv.

page xliv note 2 It omits cc. 5, 9, 28, 39, 58, 77, 82, 92, 93, which are documents; cc. 6, 50–57, 71–72, 76, 79, 80, 84–87, 91, 94, which are narrative chapters not concerned with the Ely lands, and ch. 15, which is a later marginal addition in F. The only anomaly in this selection is the inclusion of ch. 90, recording the betrayal of Alfred in 1036.

page xliv note 3 B is the later manuscript. Its readings generally agree with G—especially where the order of words differs from E and F (e.g. cc. 8 and 11). In ch. 74, where the word Berchinges occurs in EFO, it has been erased in G, while it is entirely omitted from B.

page xliv note 4 E.g. BG and F share omissions against E in ch. 62.

page xliv note 5 BG frequently have a different word order from F, where F agrees with E and the Libellus (e.g. cc. 8 and 11).

page xliv note 6 E.g. it keeps the phrases introducing charters, even when the charters themselves do not follow (cc. 8, 38).

page xliv note 7 See the textual notes to ch. 29.

page xlv note 1 E.g. in cc. 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 17, 18.

page xlv note 2 E.g. adoptatam E: adoptivam F (ch. 14); salute E: statu F (ch. 16); vestimentis E: vestibus F; reperiit E: habuit F (ch. 16).

page xlv note 3 He would not otherwise have copied the fragment of Book II, nor separated Book II from Book I by inserting between them the tract on the second translation (which comes at the end of the full Book II) and the book of miracles.

page xlv note 4 In cc. 8 and 9 E and F have lengthy additions on erasure which are not in B. It is unlikely that B could have copied F before the additions were made, since they are made in a hand which looks earlier than that of B. B could therefore derive from a copy of F Book I, taken before these additions were made, or from a source shared by E and F. In ch. 8 also B (with O) has a variant from E and F, which may come from such a common source (super Deirorum provinciam … super provinciam Eboracam adhibuit E, showing signs of erasure; super Deirorum et Berniciorum provincias … super provinciam Eboracam adhibuit F; super Deirorum, on erasure, provinciam … Eboracam hoc est Berniciorum adhibuit B; super Deirorum etc. as B, but without erasure, O). All versions make the error of not realising that the province of York is the same as that of Deira. But B and F seem to have used a source, which could not be E, with the word Berniciorum in it, perhaps as a suggested correction of the erroneous Deirorum, misunderstood by B and F.

page xlv note 5 E.g. in cc. i, 54, 55, 61, 62, 65, 66, 69, 85, 101.

page xlv note 6 E.g. in cc. 102, 109, 131, 136, 142, 148.

page xlv note 7 E.g. in cc. 104, 105, 106 (F alone adds eiusdem domus), 133, 134 (F alone adds ab illo), 137. The chief exceptions from this rule are in cc. 31 (EO add two verbs not in F); cc. 59 and 67 (where omissions in FBG are made good in EO); ch. 78 (ornamentis followed by ornatibus lined through, E; ornatibus, F; ornamentis, O) and ch. 83. Also after ch. 101 FO sometimes agree against E; e.g. ch. 101 (occurrere, E and Florence; concurrere, FO); ch. 109 (impegre, FO; omitted in E). The same distribution applies approximately where F adds words, not in E, by interlining. Up to ch. 105, with a few exceptions, these added words are in the text of O; after that they are omitted from O, as from E.

page xlv note 8 Ch. 2 (favore, EFBG; fervore, AC; favore … vel fervore, O); ch. 73 (perpetuo, with final o on erasure, F; in perpetuum, E; perpetuo vel in perpetuum, O); ch. 100 (edoctum, E; eductum, F; eductum vel edoctum, O). Cf. also ch. 89, where O shares a long addition with F, but also one sentence which is only in E.

page xlvi note 1 Book II, cc. 134, 137, 148.

page xlvi note 2 Book II, cc. 15, 128.

page xlvi note 3 O continues its preference for E up to Book III, ch. 55 (e.g. it does not share F's omission in ch. 26 and misreading in ch. 38), but follows F in bad readings in cc. 54, 56, 69, 74, 92. In cc. 95, 127, 135 it agrees again with E, and in a passage in ch. 138, where E is unintelligible, it first followed E and then produced its own emendation. In Book I, O generally agrees with F, but cf. supra, p. xlv, n. 4, where it shares a reading with B, which may represent an older version of Book I.

page xlvi note 4 It includes cc. 1, 2, 5, 6, 9, 25, 33, 41, 44–47, 51–56, 62, 72–73, 137.

page xlvi note 5 E is still a copy up to this point, and the second copyist's hand, which took over at the beginning of Book II, ch. 90, stops after ch. 43. If G cartulary used this manuscript of the L.E. it would explain why it abandons the sequence of the L.E. with the first charter (ch. 49) after ch. 43. Also ch. 43, the last chapter dealing with Bishop Hervey's time, is in itself a likely place for a break in the composition of the L.E. See supra, p. xxiii.

page xlvi note 6 By previous editors of the L.E. and the Chronicon. Their findings, discussed in Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, xli (1959), pp. 309–10, need not be examined in detail, since they are all based on the evidence of Book III, cc. 44, 45 and 61, which is cited below. The difference between them lies, not in their conclusions, but in that they found this evidence in a variety of MSS. Wharton had to rely on Book III in A, which has cc. 44 and 45, and on the book of miracles in B, which includes a copy of ch. 61. Mabillon and Papebroch had the evidence of B only. Gale had a manuscript (E) of the L.E., as had Stewart, but the latter printed only a few, incomplete notes made by H. Petrie. Cf. also Liebermann, Über Ostenglische Geschichtsquellen, pp. 225 ff. and M. Bateson in D.N.B. under Thomas of Ely.

page xlvii note 1 The nearest approximation to his style in works produced at Ely is to be found in the version of the Book I miracles in Corpus, MS. 393, Trinity College, Dublin, B.2.7 and B.

page xlvii note 2 He was one of the party which represented the monks at the election of Geoffrey Ridel (G, fo. 54v).

page xlvii note 3 He succeeded Salomon in 1177 (Bentham, Ely, i, 216–17) and was not himself succeeded before 1189 (ibid., p. 217. Bentham does not give his authority for this date, but this must be the concord ‘ facta die Sabbati prox’ post festum Sancti Andr’ anni primi electionis domini Willelmi de Lungchamp ’ which Bentham copied into Vol. VII of his notebook, C.U.L., MS. Add. 2950, from Brit. Mus., MS. Cotton, Tiberius B.ii, fo. 255). This Richard is not to be identified with the monk Richard said to have written the Gesta Herwardi (see supra, p. xxxvi), who must have been dead by the time Book II was copied into E (where he is referred to as beate memorie).

page xlvii note 4 Catalogus Scriptorum Ecclesiae, C.U.L., MS. Add. 3470, no. 169.

page xlvii note 5 De Scriptoribus Anglicis, ed. Hall, A., Commentarii de Scriptoribus Anglicis (Oxon., 1709), i, 245Google Scholar. Cf. Leland's Collectanea, ed. T. Hearne, i, pt. ii, 598 ff.

page xlvii note 6 Ed. R. L. Poole and M. Bateson (1902), p. 344.

page xlvii note 7 Scriptorum Illustrium Maioris Britanniae Catalogus (1557), p. 269.

page xlvii note 8 P. 405.

page xlvii note 9 Anglia Sacra, i, p. xlv.

page xlvii note 10 Notitia Monastica (1774), p. 35.

page xlviii note 1 Liber Eliensis, p. vi.

page xlviii note 2 See infra, App. E, p. 436.

page xlviii note 3 See supra, p. xxiii.

page xlviii note 4 See supra, p. xlvi.

page xlviii note 5 See The Chronicle of John of Worcester, ed. J. R. H. Weaver, pp. 9–10.

page xlviii note 6 See infra, Book II, Proem.

page xlviii note 7 The date of Prior Alexander's translation of the relics of the ‘ confessors ’ buried at Ely (Book II, ch. 87). This evidence for the date of Book II is roughly corroborated by Book II, ch. 54, which cannot have been written before 1144, since it mentions a silver cross ‘ quam Nigellus episcopus tulit ’ and this must be one of three crosses mentioned in Book III, ch. 89. The same chapter includes a letter from Henry of Huntingdon, described as a venerable old man, which refers to events of about 1150.

page xlviii note 8 ‘ Tempore adhuc superstitis domini Nigelli episcopi ’ …

page xlviii note 9 This agrees with the evidence of the kalendar, which precedes the L.E. in E and which gives the obit for Nigel, but not for Geoffrey Ridel. Cf. F. Wormald, Benedictine Kalendars after 1100, vol. ii and B. Dickins, Leeds Studies in English and Kindred Languages, vi, p. 15. The passio of St Thomas could also have become available by then. See Walberg, E., La Tradition Hagiographique (1929), pp. 133–34Google Scholar.

page xlix note 1 See supra, p. xxxix.

page xlix note 2 See supra, p. xxxix. This more cautious conclusion is adopted in my article, Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, xli, p. 311.

page xlix note 3 See infra, Book II, cc. 131, 132; Book III, ch. 58. Cf. Knowles, D., The Monastic Order in England (1949), pp. 118–19Google Scholar.

page xlix note 4 Book III, ch. 9.

page xlix note 5 Book III, ch. 48.

page xlix note 6 Book II, cc. 118, 141.

page l note 1 Book II, ch. 5.

page l note 2 Book II, ch. 92.

page l note 3 Book II, ch. 116.

page l note 4 Book II, ch. 93.

page l note 5 Book III, cc. 26 and 54.

page l note 6 The versions which have survived as Brit. Mus., Harley Cart. 43.H.4 and 43.H.5 appear to be not originals, but scriptorium copies (see infra, cc. 26, 54). The contents of Nigel's charter are taken over verbatim into the papal confirmations of 1139 and 1144 (Book III, cc. 56 and 85). Nigel's charter was later confirmed by himself (Book III, ch. 135; Ely, D. and C., Cart. 55) and it served as the basis for William Longchamp's charter of confirmation (Ely, D. and C., Cart. 57).

page l note 7 Ely, D. and C., Cart. 51; printed by Miller, Ely, pp. 282–83. Cf. ibid., p. 76.

page l note 8 William the Breton. The clerk Gocelin of Ely, who became a member of Nigel's familia, also witnesses this charter. Cf. Book III, cc. 78, 89, 90, 92.

page l note 9 See infra, Book III, ch. 25.

page li note 1 The manors are arranged under the headings ad victum, ad vestitum, ad luminare, ad operationem, and some of these arrangements continued to be observed after the priory gained full control. See infra, Book III, ch. 105 and F. R. Chapman, Sacrist Rolls of Ely (1907), i, 120.

page li note 2 ‘… res monachorum a rebus episcopalibus separatim ordinavi, et … separatim possidere permisi …’

page li note 3 This explanation accounts also for other differences between the charters. Manors named in the Ely charter, but absent from ch. 26, had probably been alienated (e.g. Willingham, Hardwick and Hatfield were later held as knights' fees of the bishop, Miller, Ely, pp. 183–84. Kingston was recovered by Nigel in 1135, infra, Book III, ch. 48. Hoo was exchanged, Liber M, p. 146). Of the additional possessions in ch. 26 Nigel confirms elsewhere that the monks had held Winston (‘ sicut illam melius et liberius quando ad episcopatum venimus tenuerunt ’, Liber M, p. 155) and their own court (Book III, ch. 135) in Hervey's time, and he is not likely to have been deceived, as he made a survey of the Ely revenues soon after his accession (Book III, ch. 48).

page li note 4 Book III, cc. 139–41.

page li note 5 Book II, cc. 60–70, 73–75, 81–82, 88–89.

page li note 6 Book II, cc. 7–8, 10–14, 16–27, 30–49.

page li note 7 Cc. 11, parts of 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 20, 21–23, 26, 31, 36–40, 42–49.

page li note 8 Cf. Robertson, Charters, nos. XXXI, XXXVII-XL, LIII. There are other instances concerned with Rochester, Christ Church, Canterbury, and Hereford (ibid., nos. XLI, XLIV, LIX, LXVI, LXIX, LXXVIII, LXXX).

page li note 9 E.g. pp. 48–51, 59–61, 76–79. Cf. F. M. Stenton, The Latin Charters of the Anglo-Saxon Period (1955), p. 44.

page li note 10 The proem to Book II and the concluding phrase of Book III, ch. 119 (which quotes the Latin Libellus verbatim) suggest only that there was a liber de terris sancti Ædelwoldi in the Latin translation. But the introductory phrase to Book III, ch. 120 (which proceeds also to quote the Latin Libellus) seems to imply that such a book existed before its translation into Latin (‘ in libro iam dicto sancti Ædelwoldi Anglice composuerunt, sed nunc temporis in Latinum transmutatum …’).

page lii note 1 Cc. 8–24 (except for the intrusion of transactions concerning Cambridge in cc. 18–20).

page lii note 2 See infra, Book II, ch. 24. It is unlikely that, as has been suggested, the hidage figures here given have been adjusted to agree with those sworn to at the Domesday inquest, since they rarely coincide with the totals in Domesday Book and since in cases where the tenth-century estate has been re-organised before the Norman conquest no attempt is made to identify it with the corresponding Domesday estate. See infra, Book II, cc. 8 and 9, and notes.

page lii note 3 See especially the group of estates at the end of the Libellus (infra, Book II, cc. 42–49), bought and later lost by Æthelwold, with the apparently contemporary comment that now the bishop, or the church, lacks both land and purchase money; also ch. 11, where an account of the purchase of land at Chippenham is added to the descriptio of Downham with the final comment on the six and a half predia which cost sixty shillings, while no one with any sense would value them at more than twenty.

page lii note 4 See Robertson, Charters, no. XXXIX for a list of Æthelwold's gifts to Peterborough and no. XL for a list of sureties for the purchase of estates for Peterborough.

page lii note 5 Book II, ch. 7.

page lii note 6 Except for Harting, given to Edgar in exchange.

page lii note 7 See infra, Book II, ch. 5. These details do not appear either in the Old English version of the Stowe charter nor in the other surviving version of Edgar's grant to Æthelwold of the monastery of Ely with the estates at Melbourn and Armingford.

page lii note 8 Book II, ch. 9.

page lii note 9 Book II, ch. 39.

page liii note 1 Book II, ch. 11 refers to Æthelred ‘ futurum regem tunc vero comitem’, but this could be the translator's interpolation.

page liii note 2 His name occurs in some of the transactions, but elsewhere the title abbas is used without qualification, which may indicate that Brihtnoth had not been succeeded at the time of writing. The calculation of the total hidage of the island of Ely may be connected with the measuring of the island by Leo, the prepositus in Brihtnoth's time (Book II, ch. 54).

page liii note 3 See Miller, Ely, pp. 16–25, 66–70, 74–77, 155–62, 165–75.

page liii note 4 See Professor Whitelock's foreword, supra, pp. ix–xviii.

page liii note 5 See infra, Book III, cc. 96–114.

page liii note 6 They include the place of her birth, given as Exning (Suffolk), a legendary account of her journey south from Coldingham, the dates for her marriage to Tonbert (652) and his death (654–55), and a mistaken attempt to prove that Etheldreda was the daughter of Hereswith (see infra, Book I, cc. 2, 3, 4, 13).

page liii note 7 The date is given as 970 iuxta cronicum (Book II, ch. 3, q.v.).

page liii note 8 See infra, Book II, cc. 57, 80, 84, 94, 98, 112, 113, 115, 118, 137, 140, 150 and App. D, pp. 410–13.

page liii note 9 See infra, Book II, ch. 5.

page liii note 10 Book II, ch. 92. Cf. Book I, ch. 15.

page liii note 11 The problem is discussed by Miller, Ely, pp. 9–15 and V.C.H., Cambs., iv, 1–8. The grant of the Ely hundreds and the Suffolk hundreds is included in the Stowe version of Edgar's charter and also in the summary of what may be another version of this charter in the Libellus (supra, p. lii). The Suffolk hundreds were certainly in the abbey's possession before Æthelwold's death in 984 (infra, Book II, ch. 41). That the hundred and a half of Mitford was acquired in Edgar's time we have on the authority only of the L.E. (ibid., ch. 40).

page liv note 1 Book III, cc. 9, 39, 48. Cf. Miller, Ely, pp. 165–75.

page liv note 2 See infra, App. D, pp. 426–32.

page liv note 3 E.g. Book III, cc. 37, 101; Book II, ch. 54; also Book III, cc. 78, 89, 92, 101.

page liv note 4 Even in Book III there are mistakes. A muddled introductory phrase to four papal letters (cc. 65–68) obscures the fact that Nigel himself visited Rome in 1140 (ch. 68) and four of Stephen's writs (cc. 49, 70, 71, 76) have been misplaced. See infra, App. E.

page liv note 5 Book I, ch. 1.

page liv note 6 Book I, ch. 6.

page liv note 7 Book II, ch. 91.

page liv note 8 Book II, ch. 85.

page liv note 9 Book II, ch. 91, where he is said to have been brought up in the monastery.

page liv note 10 Book II, ch. 87.

page liv note 11 Book II, cc. 98, 103.

page liv note 12 Book II, ch. 71.

page liv note 13 Æthelstan (Book II, ch. 65), Ælfgar (cc. 72, 75), Ælfwin (ch. 86). There is also a reference to the death of Asgar the Staller in captivity (ch. 96), to the death of William de Warenne (ch. 119) and the probably erroneous information that Henry I was crowned by Archbishop Thomas of York (ch. 140).

page liv note 14 E.g. on the death of Alfred at Ely in 1036 (Book II, ch. 90).

page liv note 15 Book II, cc. 102–11.

page lv note 1 See infra, Book II, cc. 109–10.

page lv note 2 Extracts from the annal for 1071 are followed by an account of the siege dated 1069 (ch. 102), followed in turn by extracts from 1067 (ch. 103), and from 1067, 1085 and 1069 (ch. 104).

page lv note 3 Cf. also accounts other than Florence dependent on A.S.C. as Henry of Huntingdon, Hist. Anglorum, p. 205 and Simeon, ii, 195 (using Florence); also Orderic Vitalis, Hist. Eccl., ii, 215–16. Freeman's view is generally accepted ‘ that the whole campaign took place in the course of the year following the departure of the Danish fleet ’ (Norman Conquest, iv, 475) in the summer of 1070 (A.S.C, E).

page lv note 4 See infra, App. D, p. 412.

page lv note 5 Book II, cc. 104–07.

page lv note 6 Book II, ch. 102.

page lv note 7 Book II, cc. 109–11.

page lvi note 1 For these details see infra, Book II, cc. 104–11 and notes. The story of the capture of the rebels is quite unreliable. Edwin, whose presence at Ely at this time is most unlikely, is said to have been captured there, while Morcar, who is reliably reported to have been captured there, is in the L.E. said to have escaped.

page lvi note 2 See infra, App. D, p. 430.

page lvi note 3 Orderic Vitalis, Hist. Eccl., ii, 185.

page lvi note 4 This might have induced the compiler to extend Abbot Thurstan's life beyond 1075.

page lvi note 5 Florence, s.a. 1070; cf. infra, Book II, cc. 101, 102.

page lvi note 6 Gesta Herwardi, p. 374.

page lvi note 7 See the Peterborough addition to A.S.C., E, s.a. 1070.

page lvii note 1 Cf. also the version of the siege in Orderic Vitalis, Hist. Eccl., ii, 215–16, suggesting that Morcar was tricked into surrender.

page lvii note 2 See infra, Book II, ch. 102.

page lvii note 3 V.C.H., Cambs., ii, 381–85, with map on p. 382, and Bentham, Ely, i, 104, n. 2, which refers to the later legend that William's army was encamped to the south of the causeway on Belsar's Hills, on the edge of the fen, in the manor of Willingham.

page lvii note 4 See H. C. Darby, Medieval Fenland, p. 110.

page lvii note 5 See T. Lethbridge in P.C.A.S., xxxiv, pp. 90–91; xliv, pp. 23–25 and in V.C.H., Cambs., i, 332–33. His view has the support of Astbury, A. K., The Black Fens (1958), pp. 49–51Google Scholar.

page lvii note 6 Book III, ch. 46, which is the source of the briefer account in Diceto, i, 248.

page lvii note 7 It adds a new date—18 December—to an already varied tradition. See infra, Book III, ch. 46.

page lvii note 8 Book III, ch. 72. There is also an interesting description of the miserable living conditions in the isle during the ‘ anarchy ’ which bears out reports from Peterborough and Ramsey (Book III, ch. 83; cf. J. H. Round, Geoffrey de Mandeville, pp. 213–20).

page lviii note 1 Book III, ch. 122. The evidence of this chapter has been needlessly condemned as a ‘ scandalous and highly imaginative narrative ’ on the grounds that it refers to Bishop Alexander of Lincoln and Pope Eugenius III who were no longer alive in 1158 (Richardson, H. G., ‘Richard Fitz Neal and the Dialogus de Scaccario’, Engl. Hist. Rev., xliii (1928), pp. 163–66Google Scholar). The compiler, however, is here making two points: (i) Etheldreda's ‘ palla ’ was pawned to provide money for the purchase of the treasurership when the king was preparing his Toulouse campaign in 1158, and (ii) this palla had already been pawned on a previous occasion (‘ similiter altera vice’) when Bishop Alexander had presented it to Eugenius III at whose command it was restored to Ely (presumably in 1145 when Alexander paid one of his visits to Rome, Henry Hunt., Hist. Anglorum, p. 278).

page lvii note 2 See infra, App. E.

page lvii note 3 It has found its way into only one major chronicle. Ralph of Diceto had good contacts with Ely in Richard Fitz Neal and William Longchamp (Diceto, i, p. lxxiv; ii, pp. xxxi–xxxii). He derived his note on the insurrection at Ely (ibid., i, 252–53) from Book III, cc. 47, 51–53, on Hugh Bigod's oath at Stephen's accession (ibid., i, 248) from Book III, ch. 46, on Archbishop Wulfstan from Book II, ch. 87 (ibid., i, 172). For the value of the L.E.'s tradition that an insurrection against Stephen and Bishop Nigel was planned in 1135–37 see infra, Book III, ch. 47.