Introduction

Amarna (ancient Akhetaten) is our best preserved pharaonic city and of central importance for the study of ancient Egyptian urbanism (Kemp Reference Kemp2012). The city dates to the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069 bc) and the reign of the monotheistic pharaoh Akhenaten, who promoted the cult of the sun god Aten above, and generally to the exclusion of, other state deities. The reign of Akhenaten is considered a transformative phase of Egyptian social history, a key episode within a broader milieu from which developed changes in religion and personal expression (Assmann Reference Assmann, Strudwick and Taylor2003; Meskell Reference Meskell2002, 196–8). Akhetaten, ‘horizon of the Aten’, was founded in Akhenaten's year 5 as the cult home for the Aten, and was famously short-lived, being largely abandoned in the years after the king's death in his year 17. During its short occupation, Akhetaten served as home to the royal family and an estimated population of up to 50,000 people (Kemp Reference Kemp2012, 271–2) who relocated to the site from other parts of Egypt, bringing with them memories of past spaces, experiences and communities. The people of Akhetaten faced an environment in which the royal family was promoted both as intermediaries to the Aten and divine figures and where—in what was a particularly radical change—there were no longer temples or state celebrations for gods other than the Aten.

Since the late nineteenth century, archaeologists have exposed large swathes of the urban landscape of Akhetaten (Kemp Reference Kemp2012), offering a remarkable snapshot of a city that underwent foundation, occupation and abandonment within a single generation. For much of its excavation history, though, Amarna was known as a settlement site without cemeteries. The tombs of the royal family and the city's elite, large rock-cut monuments, were identified early on, but the main public burial grounds remained undiscovered until 2001/2003. Excavations at the latter began in 2006, and this work continues today (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Stevens, Dabbs, Zabecki and Rose2013; also multi-authored reports from 2005 in the Journal of Egyptian Archaeology).

This fieldwork has added enormous breadth to the archaeological landscape of Amarna. The site is now one of few worldwide where we can match a population represented by a large sample of human remains to the precise urban environment they occupied. Of obvious importance for the study of health in the ancient world, this also brings opportunities to consider death as part of the experiential landscape of an ancient city, giving voice too to the population beyond the elite, still vastly understudied within Egyptology.

This paper takes a step towards understanding Amarna as a site with cemeteries, in which I seek to reintegrate the settlement and its burial grounds both as social datasets and part of a collective lived landscape. My approach is partly that of observer of, and participant in, the physical landscape as field archaeologist. Place is central to the study of these necropoles (cf. Silverman & Small Reference Silverman and Small2002; Tilley Reference Tilley1995), and arriving with any confidence at an understanding of them comes only after long-term immersion in the landscape and the amassing of a multitude of observations concerning how past human actions (choice of grave size, shape, orientation, etc.) intersected with local conditions (bedrock levels, ground slope, etc.). I am interested in exploring these intersections in the context of the religious and social milieu of the Amarna period, to approach how the city's population reconciled the physical and spiritual landscape of Akhetaten with their past experiences of death and burial, and what the cemeteries in turn indicate of Akhetaten as a city. Broader themes of core and periphery are engaged (Smith Reference Smith2014), particularly as regards the capacity of the city's population to take care of the dead. I first provide a general overview of the setting and character of the cemeteries, followed by a thematic discussion of their development in which burial data from each cemetery are looked at in more depth, and consider finally the spiritual implications of these data.

The urban landscape of Akhetaten

Understanding the built, natural and conceptual components of urban landscapes collectively is central to writing effective biographies of ancient cities. In pharaonic Egypt, spaces for the living and dead interacted somewhat differently with the natural landscape: in general terms, while settlements were constructed over the landscape, cemeteries—because of the belief in secure (subterranean) interment, amongst other factors—were more embedded within, and influenced by it. This is a tendency that is readily visible at Akhetaten.

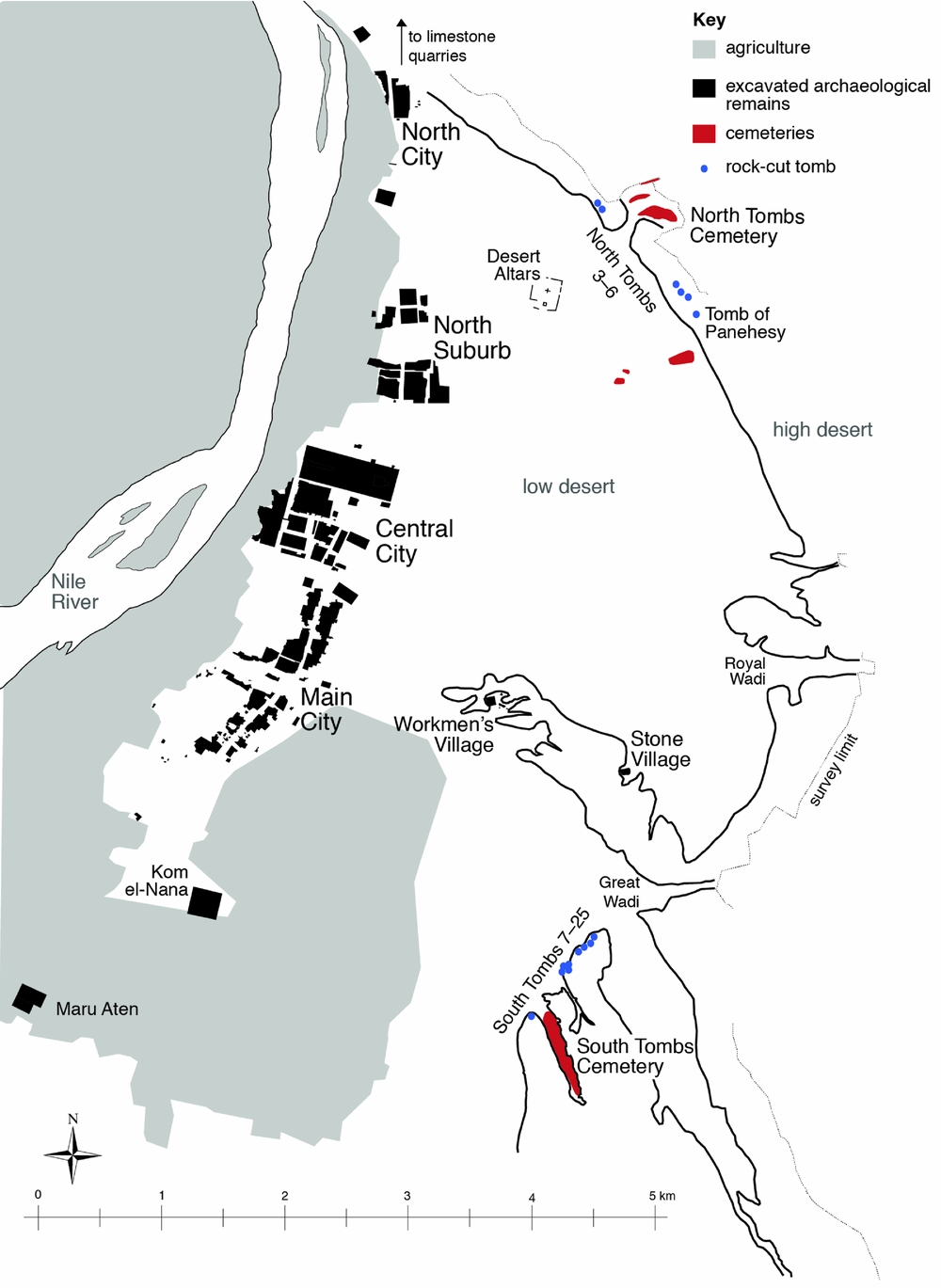

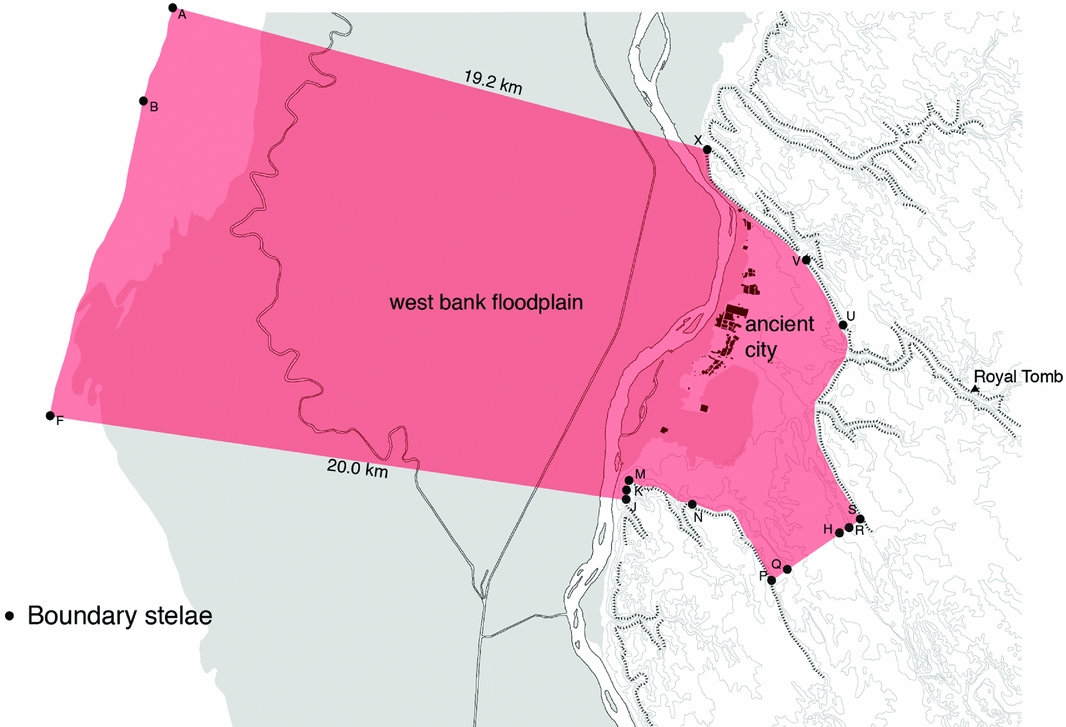

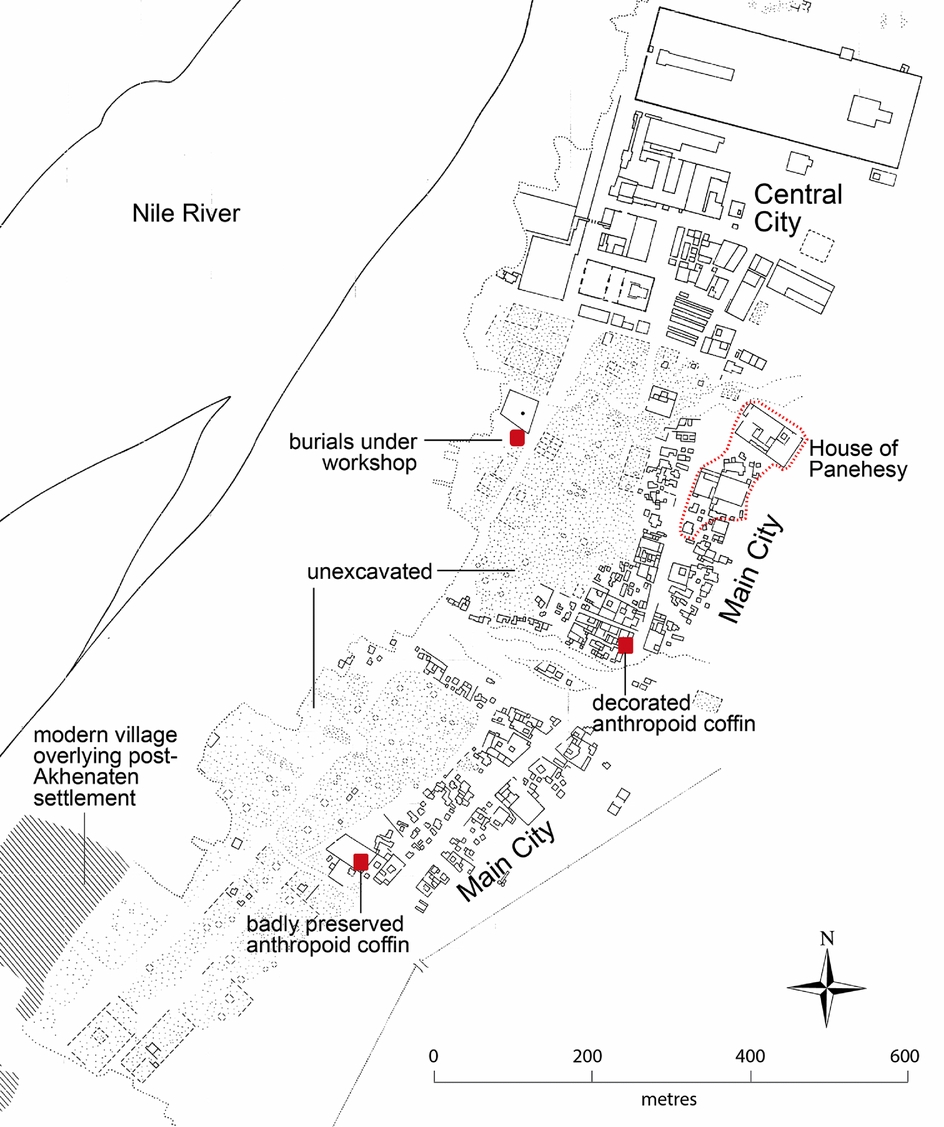

Here, the main components of the city lay within a wide desert bay on the east bank of the Nile river (Fig. 1), which has been the focus of archaeological investigation at the site. The broader landscape was also exploited for its natural resources, with a network of quarries in the limestone cliffs to the north (De Laet et al. Reference De Laet, van Loon, Van der Perre, Deliever and Willems2015), and the floodplain on the west bank seemingly used as agricultural land. The broader periphery of the city—demarcated by Akhenaten through a series of Boundary Stelae (Fig. 2)—is poorly understood and now largely lost under fields, but likely included a substantial population, partly comprising farming communities that existed before Akhetaten itself, along with satellite settlements connected with the new city (De Laet et al. Reference De Laet, van Loon, Van der Perre, Deliever and Willems2015; Kemp Reference Kemp2012, 40; Willems et al. Reference Willems, Vereecken and Kuijper2009).

Figure 1. Amarna map with the main non-elite cemeteries shown in red. (Base map: Barry Kemp, including survey data by Helen Fenwick.)

Figure 2. The Boundary Stelae of Amarna. (Reproduced courtesy of Barry Kemp.)

Within the eastern bay, the urban landscape, both built and natural, was divided into three parts.

The riverside city

Spread along the riverbank was the core city, its hub a cluster of temples, palaces and civic buildings (the Central City). Residential areas extended to the south and north: the Main City, North Suburb and North City (Fig. 1). The large exposures of mud-brick houses here have prompted two fundamental observations on urban society at Akhetaten. The first is that, when the frequencies of house ground-floor areas are plotted, the profile suggests a population that was relatively evenly graded in socio-economic status (Kemp Reference Kemp1989, 298–300; Fig. 3), albeit with a fairly distinct division at about the 100 sq. m mark that probably separates residences of officials and administrators from those of workers and craftsmen (Shaw Reference Shaw1992, 159–60). Smaller houses, in turn, tend to cluster around larger estates in a manner that suggests a patron-provider model, officials and artisans living in the latter acquiring goods and services from occupants of smaller houses on behalf of the state in return for basic provisions (Kemp Reference Kemp2012, 43–4); the Main City may have been the hub of urban industry and the North Suburb perhaps occupied especially by mid-level scribal officials (Shaw Reference Shaw, Bourriau and Phillips2004, 23). There remain, however, many questions about the interactions between people, and with the built and natural environment, that gave Akhetaten life and shape (cf. Smith Reference Smith2010, 173).

Figure 3. The frequency of houses excavated across Amarna with different ground-floor areas. Sample size 793. (Reproduced courtesy of Barry Kemp.)

The low desert

The second element of the eastern bay was an expanse of flat, fairly featureless desert that extended to the cliffs of the high desert (Fig. 1). A striking feature here is a network of roadways thought to have served in part as patrol routes and potentially boundary markers (Kemp Reference Kemp2012, 155–61; Petrie Reference Petrie1894, 4–5; Stevens Reference Stevens2012, 77–80, 414–21). They co-exist with tomb scenes showing soldiers monitoring the probable outskirts of Akhetaten (e.g. Davies Reference Davies and de1906, 17–18, pl. XXVI), seemingly to guard against incursions, but also to regulate activity here.

The main built elements on the low desert were a group of isolated cult complexes, one of them possibly connected with elite mortuary cult (Kemp Reference Kemp and Kemp1995, 448); and two small villages, constructed against a low plateau, the Workmen's Village and Stone Village (Fig. 4). These housed workers engaged in desert-based activities, including the construction of the royal, and perhaps elite, tombs (Kemp Reference Kemp1987; Stevens Reference Stevens2012). Each had its own cemetery, apparently quite small, although neither has been extensively excavated (Stevens Reference Stevens2012, 384–411; Stevens & Rose forthcoming; Weatherhead & Kemp Reference Weatherhead and Kemp2007, 407–14). While it is difficult to incorporate the village cemeteries into broader narratives, two points can be noted: they lie very close to living areas, and the excavated graves are shaft-and-chamber tombs, rather than pit graves. The latter is a product, at least in part, of the plateau having a crust of clay-like rock that can easily be carved. The Workmen's Village also had a series of chapels used partly as spaces to commemorate ancestors (Bomann Reference Bomann1991; Weatherhead & Kemp Reference Weatherhead and Kemp2007).

Figure 4. The desert villages, showing the location of their cemeteries. (Workmen's Village base map: Barry Kemp; survey data by Helen Fenwick incorporated into both.)

The eastern cliffs and cemeteries

The third element of the bay was the cliff face that bounded it to the east, broken by several wadis, two of which are particularly prominent. One was chosen for a new royal cemetery, extensively surveyed and containing at least four tombs, including that of Akhenaten (see Fig. 2). The second (the ‘Great Wadi’) has a profile that recalls the hieroglyph for ‘horizon’ and may have prompted Akhenaten to choose this particular stretch of land for his city (Aldred Reference Aldred1976). It was here at the cliff face that the main cemeteries were located, forming two groups to the northeast and southeast of the riverside city (Fig. 1).

The non-elite cemeteries

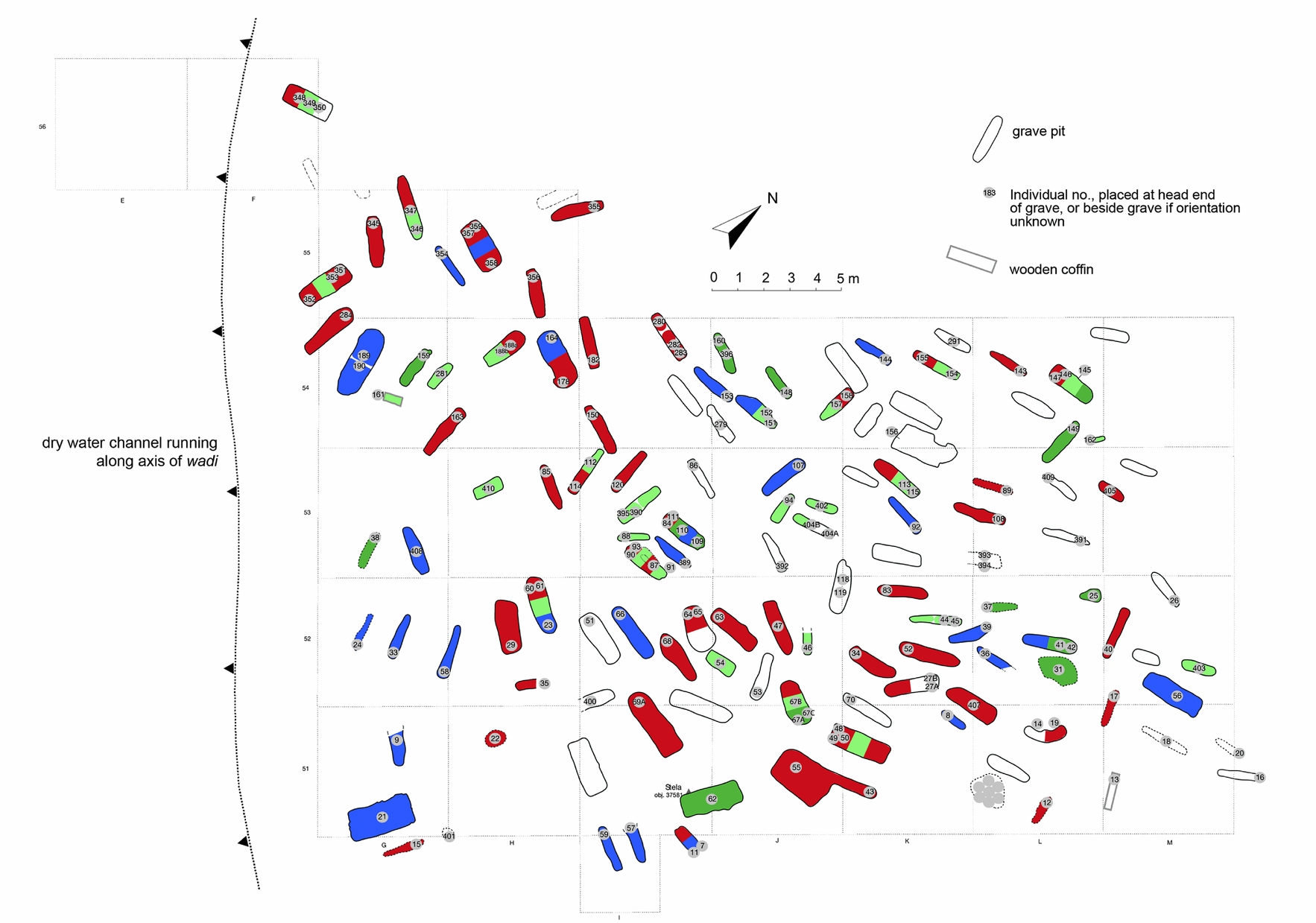

Each cemetery combined rock-cut tombs in the cliffs (the North and South Tombs; Fig. 1) with large expanses of primarily pit graves. Excavation has focused mainly on the South Tombs Cemetery, where 381 graves were excavated from 2006–13 across four main sample areas (Fig. 5). The graves lie in a long, sand-filled wadi, where the soft rock of the desert villages barely outcrops. The site has been badly robbed, probably in the distant past, but much burial evidence remained. It is a mixed burial ground of adult men and women, subadults and infants, its demography consistent overall with that expected of a cemetery of this antiquity (see Fig. 10).

Figure 5. The South Tombs Cemetery, showing excavated areas (bottom) and the general landscape (top). In the photograph, the Lower Site is in the foreground, with the view to the southeast. (Base map by Helen Fenwick.)

The deceased was wrapped in textile and enclosed in a roll of matting, or occasionally in a coffin of wood, pottery or mud; there was probably no attempt to preserve the body other than through wrappings. Finds of pottery vessels, sometimes with botanical remains, suggest offerings to sustain the deceased in the afterlife. Other grave goods were rare, comprising mostly amulets and jewellery.

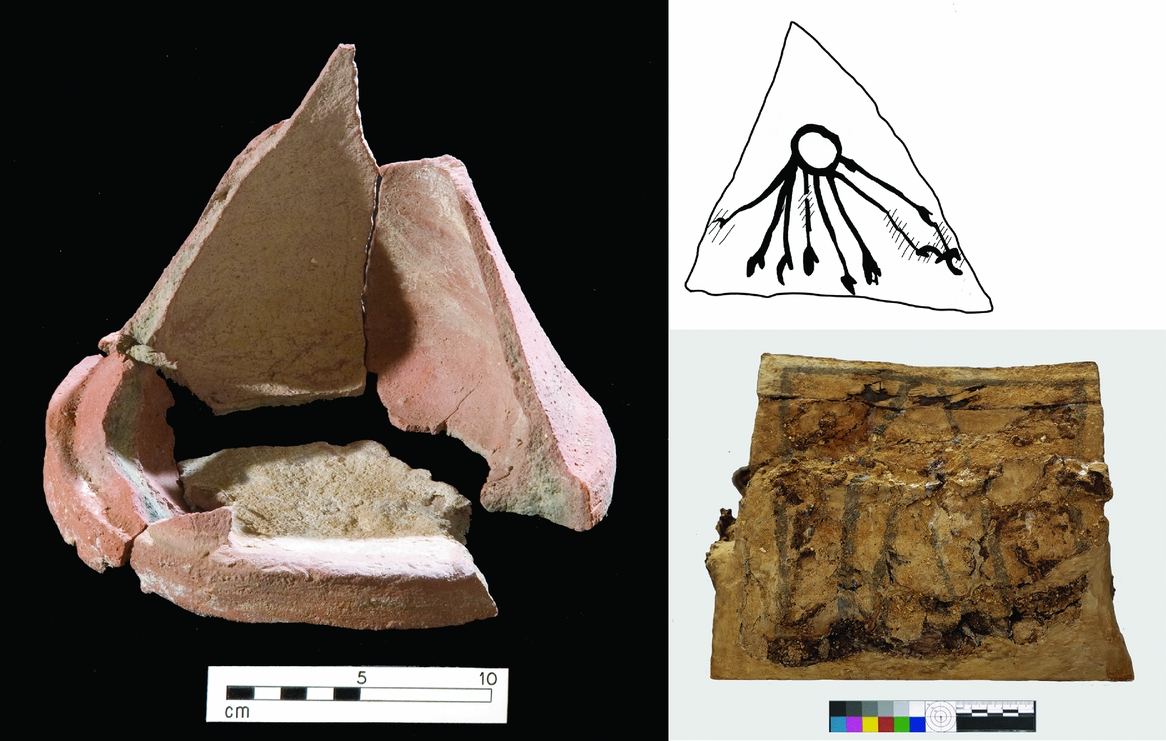

Although most of the original surface has been destroyed, the majority of burials seem to have been marked only by a cairn of limestone boulders (Fig. 6), while scattered pieces of mud brick may represent occasional brick superstructures (cf. perhaps Kampp Reference Kampp1996, vol. 1, 107, fig. 81). Two limestone pyramidians (miniature pyramids) were recovered, along with up to 15 stelae, most with a distinctive pointed shape (Fig. 7). Carved decoration surviving on three examples can be resolved into an image of the deceased receiving offerings. The stelae were presumably erected as grave markers. They are amongst the earliest examples of pointed stelae; these, and pyramids at private tombs, were gaining popularity under Akhenaten's father, Amenhotep III, but are more widespread in the post-Amarna period (Bosse-Griffiths Reference Bosse-Griffiths1955, 60, fig. 1; Kampp Reference Kampp1996, vol. 1, 5–109; Kampp-Seyfried Reference Kampp-Seyfried, Strudwick and Taylor2003, 9, n.39). The Amarna pointed stelae and pyramidians seem intended to combine a memorial representation of the deceased with a model of a rock-cut tomb, serving as self-contained body–tomb substitutes (see also Tawfik Reference Tawfik2013, with references). Jointly, they potentially took on roles as landscape modifiers, markers of ritual and liminal space, and solar symbols.

Figure 6. Reconstruction of the South Tombs Cemetery. View from the Lower Site, facing southeast into the wadi. The location of graves in the foreground is based upon excavated burials, and the positions of stelae here likewise projected from excavation data. The reconstruction is intended to convey the starkness of the landscape, overall anonymity of the site and manner in which the cemetery might have spread in clusters from the mouth of the wadi along its length. (Reconstruction: Fran Weatherhead.)

Figure 7. A selection of stelae and a pyramidian found at the South Tombs Cemetery.

At the north of Amarna, three separate burial grounds have been identified (Fig. 1). The largest is again contained within a break in the cliff face (Fig. 8). Two seasons of fieldwork have been undertaken here, in 2015 and 2017, with over 140 graves excavated (Dabbs & Rose Reference Dabbs and Rose2016; Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Dabbs, Shepperson and King Wetzel2015). These contained at least 232 individuals, 105 of which have been subject to bioarchaeological analysis so far (Dabbs & Rose Reference Dabbs and Rose2016; Stevens et al. Reference Stevens, Dabbs, Shepperson and King Wetzel2015). The site is similar to the South Tombs Cemetery in that it contains modest pit graves, although important differences exist. The rate of artefact recovery here is extremely low, and not a single wooden coffin has been found. The number of graves containing more than one person is also striking (c. 43 per cent at present, which may change somewhat as commingled burial groups are analysed). While multiple burials occurred at the South Tombs Cemetery, they were not typical of the site, attested mostly in one sample area (the Upper Site, comprising at least 21 per cent of burials here; see Fig. 14). At the South Tombs Cemetery, graves containing multiple interments were usually cut wider than normal to accommodate bodies side-by-side, whereas at the North Tombs Cemetery it is far more common to find bodies stacked one on top of another in graves only slightly wider than normal, although sometimes longer than seems necessary (Fig. 9). Most striking is the demography of the site, with the individuals so far analysed revealing a population almost entirely of late subadults and young adults, c. 7–25 years of age (Dabbs & Rose Reference Dabbs and Rose2016; Fig. 10).

Figure 8. The North Tombs Cemetery, showing areas excavated in 2015 and 2017, and general landscape (top) facing northeast from near the mouth of the wadi. (Base map by Helen Fenwick.)

Figure 9. A multiple burial at the North Tombs Cemetery, containing four individuals interred in three layers.

Figure 10. Comparison of the age distribution across the South and North Tombs Cemeteries (based on samples of 392 and 105 respectively). (Analysis led by Jerry Rose and Gretchen Dabbs.)

The other two northern burial grounds, yet to be excavated, are smaller. One lies at the base of the cliffs containing the officials’ tombs, lying just beyond the southernmost of the tombs that were substantially finished. This belonged to an official named Panehesy, who was responsible for offerings made to the god in the Great Aten Temple (Fig. 1; Davies Reference Davies and de1905a, 9–32). Based on surface evidence, the burials at this cemetery are again pit graves. The second burial ground lies a few hundred metres to the west (Fig. 1) and seems to comprise both pit graves and larger chamber tombs, the latter cut into the edge of a low rise where the clay seen at the desert villages again outcrops.

We must now have a fairly complete spectrum of burial places for the population of Akhetaten, at least those living on the east bank, allowing that other small cemeteries may remain undiscovered. It is also conceivable that some officials constructed their tombs in hometowns beyond Akhetaten (particularly those of lower rank: Auenmüller Reference Auenmüller, Dębowska-Ludwin, Jucha and Kołodziejczyk2014); not all officials known to have had a villa are represented at the rock-cut tombs (Arp Reference Arp2012). We cannot rule out the possibility that others amongst the population, too, repatriated their dead if they had the means, especially those who came to Akhetaten from nearby settlements. There is some evidence that the occupants of the Workmen's Village removed their dead to Thebes when Akhetaten was abandoned (Stevens & Rose forthcoming), although only after first interring them in the hillside behind the village. We may also be missing some burials of extremely poor or outcast individuals for whom ad hoc methods of disposal were perhaps employed (Baines & Lacovara Reference Baines and Lacovara2002, 12–13).

In terms of numbers, extrapolating the individuals excavated at the South Tombs Cemetery across the area covered by the cemetery as a whole gives an approximate figure of 6000 deceased. The number for the North Tombs Cemetery is more difficult to estimate because of variability in burial density across the site, but likely falls in the range of 4000–5000. It is too early yet to model population counts for the other northern cemeteries, but these will certainly be lower, while the numbers of dead at the desert villages seem unlikely to have exceeded 100–300 or so. Overall, therefore, we can estimate that at least 10,000–13,000 people were buried in the east bank cemeteries of Akhetaten. As regards the study of human remains, both South and North Tombs Cemeteries show widespread dietary deficiencies and heavy labour and pathogen loads, implying poor overall health and difficult working lives (Dabbs et al. Reference Dabbs, Rose, Zabecki, Ikram, Kaiser and Walker2015; Rose & Zabecki Reference Rose, Zabecki, Ikram and Dodson2009). The human remains provide a far more acute view of the hardships of everyday life than the ruins of the city itself, where we are probably still inclined to see the best in the quaint mud-brick houses.

Placing cemeteries in the urban landscape

The question of who was responsible for situating the cemeteries of Akhetaten is a fundamental one. Despite the long tradition of funerary studies within Egyptology, little is known of how non-elite cemeteries were organized, both internally and as regards urban space and populations. Detailed written evidence is scarce and social analyses of burial data are undeveloped, particularly for historic periods (Richards Reference Richards2005, 49–74), while the urban contextualization of burial data is often hampered by difficulties isolating coeval settlement and cemetery horizons.

Akhetaten offers an example of a specific type of Egyptian city, at which the royal family themselves were resident, and which was created as a cult arena. It was not unique in these aspects, but because it was abandoned so close in time to its foundation, we can suppose that there remained a level of commitment to Akhenaten's vision, as far as this existed. Did public burial space figure in this, and to what extent did background ideas regarding death and burial influence the development of the broader urban environment?

Vision has been a key theme of discussions of Akhetaten as a city, particularly the question of whether it was designed according to a symbolic blueprint (see Kemp Reference Kemp2000). It is widely accepted that the city's open-air temples engaged with the display of the sun-god overhead, while the alignment of the Small Aten Temple to the royal wadi suggests the elevation of the eastern horizon, or part of it, to a ‘symbolic landscape’. While some view the city as a carefully designed stage for the Aten cult, others see little symbolic significance in its layout (Kemp Reference Kemp2000, with references); they draw upon foundation texts that Akhenaten had inscribed upon the Boundary Stelae (Murnane & Van Siclen Reference Murnane and Van Siclen1993), which give little indication of symbolic vision, a reminder that the king's ideas for Akhetaten were not necessarily fully formed at the time of its foundation.

Few would argue that death was one of the forces that explicitly shaped Akhetaten—this is not in keeping with what we know of Egyptian cities—but attitudes towards death and the dead must have been an underlying influence. The ancient Egyptians had well-formed ideas regarding space for the dead. The belief that the afterlife was effectively an idealized continuation of life itself created a degree of parallelism between space for the living and the deceased, with tombs conceived of as houses for the dead, elite tomb chapels reflecting elements of domestic architecture and necropoles sometimes referred to as niwt or ‘town’ (Snape Reference Snape2014, 120–21). Concurrently, a degree of separation between spaces for the living and dead was preferred, probably stemming from the idea that the dead could move beyond the grave and act against the living. The degree to which this was maintained depended on local landscape and the availability of inhabitable ground (Bietak Reference Bietak and Weeks1979, 101), but communal burial grounds outside settlement limits were always favoured over interment within occupied settlement spaces.

Amarna presents a rather neat illustration of an ideal Nile Valley landscape, with something like a zone of the living (the riverside city) and of the dead (the eastern cliffs), and perhaps even a ‘no-man's-land’ in between, although this should not be pressed too far. Jointly, it demonstrates the flexibility in how much separation was necessary between the living and the dead at the desert villages, where the cemeteries are very close to the settlements. At the Stone Village, the cemetery seems to be contained to a piece of land enclosed within ‘roadways’, raising the possibility that these served as symbolic barriers to define and contain the liminal space of the dead (Stevens Reference Stevens2012, 78).

For the North and South Tombs Cemeteries, the collection of large numbers of deceased in burial grounds distant from living areas suggests a degree of collective planning regarding organization of the dead that went beyond household- or small-community-based decision making. If the latter were predominant, we might expect more small cemeteries like those at the desert villages: perhaps a string of burial grounds along the desert adjacent to the riverside city. A degree of city-level organization is supported, too, by the idea that fairly tight control was exerted over the eastern boundary of Akhetaten, making it an unlikely location for the spontaneous development of community cemeteries, although the little cemetery in the desert west of the North Tombs (Fig. 1) has something of this character. The Boundary Stela texts state that the king will allow for the cutting of tombs for the priesthood in the eastern mountain (Murnane & Van Siclen Reference Murnane and Van Siclen1993, 41, 171, 174), implying, it seems, that access to the cliffs required a royal decree, at least to construct a monumental tomb (also Arp Reference Arp2012, 139).

Burials in the Main City: adding a temporal dimension

For perspective on the development of the cliff-side cemeteries, we can look to excavations that took place in the Main City in 1924, when large-scale clearance exposed burials interspersed amongst houses (Griffith Reference Griffith1924, 302) that are not obviously examples of much later intrusive graves. One concentration was found at a large estate at the northeast edge of the Main City belonging to a man named Panehesy, probably the same Panehesy who owned the tomb with nearby pit-grave cemetery at the north of the site (Fig. 11). The graves continued to appear sporadically along the eastern fringe of the city, but were not found moving westwards (Griffith Reference Griffith1924, 302).

Figure 11. Preliminary distribution map showing burials below and around houses in the Main City; others likely remain to be identified amongst the excavation records. (Base map: after Kemp & Garfi Reference Kemp and Garfi1993.)

The excavation archive (of the Egypt Excavation Society) indicates that they were simple pit graves, and represent two phases of activity. Some predate the Amarna period houses, being well embedded beneath architecture (Fig. 12), but others run alongside walls as though cut secondarily to these. Some of the latter contained pottery consistent with a late Dynasty 18–early Dynasty 19 date (Pamela Rose pers. comm., 2016); another yielded a ring inscribed for Tutankhaten (obj. 24/686), in whose reign the royal court abandoned Akhetaten. This prompted the suggestion that some of these burials were ‘survivors of the inhabitants who lingered on when the place had been partly deserted’ (Griffith Reference Griffith1924, 302). Assuming the ring is not an heirloom or reused, this seems a reasonable idea. We now know that a small settlement remained in the eastern bay for some time, its ruins buried beneath a modern village at the south end of the ancient city (Kemp Reference Kemp and Kemp1995, 466–8; Fig. 11). Another house burial, discovered in 1912 (Borchardt & Ricke Reference Borchardt and Ricke1980, 106, plan 29; Fig. 11), contained a wooden coffin with painted decoration that has some characteristics of coffins from the South Tombs Cemetery and is not obviously later in style (Bettum Reference Bettum2015, 32 and pers. comm., 2016). We can probably add to these burials a group of graves found beneath an Amarna period workshop on the southern edge of the Central City (Fig. 11; Nicholson & Hart Reference Nicholson, Hart and Nicholson2007).

Figure 12. An early burial, over which one of the Main City houses has been constructed. (Egypt Exploration Society Amarna Archive Negative 24/56.)

Can we view these scattered burials as temporal ‘bookends’ to the large cliff-side cemeteries? No earlier settlement has ever been identified to which we might assign the early graves. One might have been lost under cultivation, but it seems telling that the burials trail along the eastern edge of the Main City, as though respecting the early limit of Akhetaten itself here. They are conceivably graves of the first inhabitants of Akhetaten, including workers preparing the city in advance of the main settlement, the burials gradually overbuilt by the expanding settlement. The workshop excavators, while acknowledging this, suggested there might have been reticence to disturb recent graves, and preferred to see these burials as somewhat earlier in date (Nicholson & Hart Reference Nicholson, Hart and Nicholson2007, 31). But pragmatism may have won out, spurred on by disconnections as regards personal relations and status between the deceased and incoming settlers; Panehesy is unlikely to have had family members amongst the poor burials that underlay his house.

These early burials could suggest that somewhat impromptu solutions to the disposal of the dead were implemented in the founding years of Akhetaten and something then prompted a centralized solution to the disposal of the dead: the influx of settlers, perhaps, or, after a delay, the inconvenient mixing of settlement and burial space that was beginning to occur. This scenario provides a possible explanation for an unusual burial at the South Tombs Cemetery, containing two adult females and two children, where one of the adults seems to have been reburied (Ind. 90: Fig. 13). Her entire skeleton was present, but disarticulated, the bone padded out with mud-brick, potsherds and a roll of matting to restore its shape. Was she one of these early burials: not forgotten, but relocated to the South Tombs Cemetery at a time when other family member/s had died?

Figure 13. A grave at the South Tombs Cemetery containing the reburial (?) of an adult female (Ind. 90). (Illustration: Mary Shepperson.)

The secondary burials speak, on the other hand, to the abandonment of the cliff-side cemeteries, perhaps soon after the royal family left. It must have been partly a matter of convenience, but security likely played a role: the threat of tomb robbery was probably considerable. The practice of inserting burials into abandoned settlements, while common in ancient Egypt, is not well researched. The concentration of burials around the house of Panehesy is striking and raises the question of whether this was prompted by community memory of a pre-existing cemetery, or of Panehesy's important position in the Aten cult.

The Main City burials provide archaeological testimony to the fairly logical notion that central involvement was necessary to maintain the cliff-side cemeteries, and that community-level responses to the disposal of the dead were the natural fallback when this was absent. Here, the city takes on something of the responsibility of disposing the dead, performing an ‘urban service’ of sorts (for which, see Smith et al. Reference Smith, Dennehy, Kamp-Whittaker, Stanley, Stark and York2016; this designation need not rob burial of its social importance). The level of state interest in the public cemeteries, nonetheless, can probably be characterized as low-level. On the Boundary Stelae, there is no mention of provision of burial space for the broader population, nor of the urban aspect of Akhetaten generally (Murnane & Van Siclen Reference Murnane and Van Siclen1993, 171). It is clear that the housing areas developed in a fairly organic way, although with a sense of lead-and-follow: elite residences placed on the landscape, and those of lower-ranking households then built around them. We might extend this to the non-elite cemeteries. It is probably no coincidence that the rock-cut tombs lie adjacent to fairly enclosed sand-filled wadis, which provided contained and sheltered locales for the two largest burial grounds. There are not many other wadis of this kind, suggesting that when the location for the elite tombs was chosen, provision for burials of the broader population was simultaneously made. At the same time, there is little obvious built infrastructure connected with the public cemeteries, such as check-points, guard posts or roadways. Any protection that they were afforded might simply have been a side-effect of their location near the elite tombs and the general strong-arm approach to controlling the city's eastern boundary. A sense of state detachment fits the fact that there was scope for the development of community cemeteries at the workers’ villages, and perhaps at the little burial ground out in the desert west of the North Tombs.

An internal view: shaping burial space

The South Tombs Cemetery: kinship, community and status

At an internal level, the South Tombs Cemetery conveys an overall sense of organic development; there is no obvious spatial framework in the layout of the graves, and the term ‘self organized’ seems a good fit. Burials of adult women, adult men, and subadults and infants are intermixed (Fig. 14), and it is a reasonable guess that family-level agency was a leading force in shaping the burial landscape; ongoing human remains analysis may help to clarify this.

Figure 14. Upper Site (South Tombs Cemetery) showing graves of adult women (red, aged 15+ years), adult men (blue, aged 15+ years), juveniles (dark green, aged 7–14 years) and infants/young children (pale green, aged up to 7 years). Uncoloured graves contain too little skeletal material to analyse in respect of sex. (Skeletal analyses led by Jerry Rose and Gretchen Dabbs.)

Careful excavation has allowed a closer view of the dynamics of grave cutting that supports this idea. The graves, although simple, are often very well shaped, especially when cut into sand that is deep and reasonably compact. Care is taken to create near-vertical walls, the graves never intersect, and they often end at a horizon of sand that is only slightly more compact than the overlying fill. There are also subtle variations in the shape of the grave according to the type of burial container used (Fig. 15) and, across much of the cemetery, a careful matching of grave and coffin size. This suggests a consistency in approach and familiarity with local geology that places grave cutting as a specialized role, and not a task undertaken ad hoc by funerary parties. Consecutively, though, it implies that graves were not pre-prepared, but cut only once these parties had brought the coffin out to the cemetery, and had presumably selected the grave location itself.

Figure 15. Sample graves from the South Tombs Cemetery showing how pits containing matting coffins tend to have rounded ends; those with wooden box coffins are often cut with squarer ends; and graves with anthropoid coffins can be cut with one curved and one blunt end, mimicking the shape of the coffin.

Beyond possible kinship in the organization of the graves, other social relationships, including those that might reflect urban sub-communities, are far more difficult to elucidate. This is partly due to the modest and largely uninscribed nature of the remains and loss of the original surface. The cemetery may, however, have been a confusing and anonymous landscape for those in the past, too, and families perhaps relied in part on memory to negotiate it, with distinctive grave markers and landscape features serving as navigational aides. We can only wonder to what degree people were buried in the neighbourhoods in which they lived, communities that were probably underpinned by a strong sense of extended family. It is also possible to imagine ways in which living communities were re-ordered: people may have married into other ‘village clusters’, but sought burial close to their families, for instance. The large size of the cemetery, and perhaps the restricted shape of the wadi, potentially exacerbated the re-ordering of communities from life to death, family plots, as far as they existed, becoming difficult to hold on to as the cemetery grew and negotiations regarding the use of space became increasingly complex.

One relationship that does not obviously translate into the burial environment is that of co-dependence between the elite and workers. We might have expected small burial grounds below individual rock-cut tombs, modelling in death the ‘villages’ of dependents around the large urban estates. The one case where this might occur is at the cemetery close to the tomb of Panehesy. If this connection is purposeful, Panehesy's elevated position in the Aten cult seems pertinent: is this a burial ground for temple staff who served him in life? The cemetery, however, covers a fairly substantial area (it is at least 200 m long) and may be too large for this role alone, raising the possibility that it served more as a general burial ground for the residents of the northern suburbs. Future excavation may shed light on this.

At the South Tombs Cemetery, we might have something of a reversal of this dynamic, in which relatives of officials owning rock-cut tombs were perhaps integrated in the wadi cemetery. These families must have suffered deaths during the occupation of Akhetaten, yet few of the rock-cut tombs show evidence of burial remains or shafts, either inside or nearby (for exceptions: Davies Reference Davies and de1905b, 2, 16–17, 26–7; Reference Davies and de1906, 9, 21, 25; Reference Davies and de1908, 8, 12). The deceased were perhaps interred in tombs beyond Akhetaten, but if not we might look to those graves in the wadi containing decorated wooden coffins in seeking their burials. Such coffins were found in around 5 per cent of graves and are the most obvious surviving ‘status markers’, spread along the wadi in a way that leaves little impression of socio-economic zoning.

Other than the use of different coffin types, there is little direct scope to model socio-economic profiles, although this needs more thought. There is clearly a correlation with the house-size profile (Fig. 3) in that there are small numbers of rock-cut tombs and large numbers of pit graves. Allowing for the possibility that some officials are not present at all in the funerary record of Amarna, there remains potential for the integration of higher-ranking families into communal burial areas and the flattening-out of expressions of difference through the lower end of the spectrum (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Stevens, Dabbs, Zabecki and Rose2013, 74), the pit graves being so uniform in appearance and content. Landscape undoubtedly played a role here, the sandy geology not suited to the cutting of complex tombs, including family graves, and we may in part be seeing a shift from collective to individual expression. The significance of the multiple burials at the South Tombs Cemetery remains to be clarified: some could be family tombs, but whether for individuals who died at the same time, or as attempts to create chambers that were re-opened, is not clear. In this milieu, it is possible that the funerary stelae—model tombs—might sometimes be aspirations to more elaborate family tombs, or memories of these left behind in hometowns.

Overall, the South Tombs Cemetery seems to fit a regular suburban population presented with a burial landscape that was not necessarily one they would have chosen for themselves, but who were then the leading agents in dictating how it developed. It seems a good fit to a population represented by the Main City (Fig. 1), which is the natural guess as a primary, although not necessarily sole, feeder population, given its location. If we accept a figure of 6000 dead, and an occupation period of 15 years, there would have been around one funeral a day at this cemetery: an alternative perspective of the impact of death on urban society at Akhetaten, somewhat difficult to grasp in age-at-death profiles.

The North Tombs Cemetery: a hidden urban community

At the north end of Amarna, a more complicated picture is emerging as regards the organization of the burial grounds and their relationships to settlement areas. There is little immediate sense at the North Tombs Cemetery of family agency in the arrangement of the graves, given the restricted age range of the deceased, while the general impression of poverty and large number of multiple burials, often roughly laid out, suggests reduced overall ‘care for the dead’.

In seeking to explain the unusual burial profile, several interpretive pathways present themselves. One is a disease-driven explanation: an epidemic strike, or the different treatment of a diseased portion of society at the time of death. To explain the restricted age-at-death profile, however, it seems necessary to introduce a further variable. Could they be a workforce, selected on the basis of youth and then subject to such difficult working and living conditions—emerging in the preliminary study of the human remains (Dabbs & Rose Reference Dabbs and Rose2016)—that they were particularly susceptible to diseases, including those endemic to the region, resulting in large numbers of deaths?Footnote 1 The stacking of bodies, sometimes in graves that are cut too large, supports this: we might imagine a designated gravedigger pre-cutting a generously sized pit to receive a toll of dead for the day, or a few days. There is little doubt that the multiple graves often represent individuals buried at the same time. Although many were badly disturbed, in only one grave was there evidence in the form of layers of sand between skeletons that might suggest the grave was filled progressively. More often, the bodies are so tightly packed that they seem likely to have been placed in the grave together; sometimes they are wrapped together in the same burial mat, in which case there is no doubt.

The North Tombs Cemetery, with its large number of young individuals, may offer evidence of the enforced labour system known to have been used on major projects in ancient Egypt, but rarely witnessed archaeologically. It may be noteworthy that the main limestone quarries, from which the stone for Akhenaten's temples and palaces was sourced, are also located north of the city. We might imagine these labourers perhaps carting materials to and from building sites, amongst other tasks connected with the city's construction and maintenance (making mud-bricks, carrying water, etc).Footnote 2

The absence of obvious family groupings at the cemetery suggests that they were living separately from their families at the time of death, at least as a whole, and were not returned to them for interment. It is not clear where they were living, however, or where they originally came from. There are few traces of settlement around the quarries themselves. These settlements could have been very basic work camps with few solidly built structures, although we would still expect some archaeological trace, particularly pottery. Perhaps they were living in areas now lost under agriculture, or amongst the desert wadis, some of which are subject to flash floods capable of washing away shallow archaeological remains. If they were conscripted originally from the east bank city, we might expect families to have been able to claim the bodies for burial (although this is perhaps an idealized view). An alternative is that they came from peasant farming families living in the city's hinterland, including the west bank of the Nile, the river forming a barrier preventing the return of bodies upon death, or that they were brought to Akhetaten entirely separate from their families, potentially from outside Egypt itself. They need not, of course, have had a single origin. In any case, while the hinterland and peripheral settlements of Akhetaten may now be largely inaccessible, burial data from the South and North Tombs Cemeteries may offer an alternative pathway to access something of the city's core–peripheral dynamic, particularly as regards patterns of inequality in the experience of death and burial.

Death at the horizon of the Aten

The cemetery excavations also provide an unparalleled point of reference for public reaction to Akhenaten's monotheism. ‘Atenism’ tends to come across as a philosophy of life and less developed, or less expressive, in its frameworks for understanding death (Assmann Reference Assmann, Strudwick and Taylor2003, 51; Hornung Reference Hornung and Lorton1999, 95–104, 137–8). Evidence from elite tombs suggests the dead now survived in the world of the living, sleeping in the tomb and worshipping the Aten at sunrise inside temples; tomb owners petition Akhenaten, Nefertiti and the Aten to see the sun-god after death, and receive a proper burial and offerings (Wilson Reference Wilson1973, 239–40). The pre-eminent funerary god Osiris is largely absent, and state festivals for traditional gods that incorporated offering and feasting for the dead did not continue.

The cemetery work is taking place against a backdrop of broader investigation on how the city's religious institutions might have served a private funerary cult; the discovery of possible private mortuary installations in the Great Aten Temple is particularly significant (Kemp Reference Kemp2015, 14–15; see also Stevens Reference Stevens2006, 313; Williamson Reference Williamson2013, 147–51; forthcoming). Something of a rethink is jointly occurring regarding public interaction with the Aten cult, prompted partly by a move towards archaeological data and issues of reception and personal agency (e.g. Bickel Reference Bickel2003; Fitzenreiter Reference Fitzenreiter2008; Stevens Reference Stevens2006). Was the worship of the royal family/Aten via domestic icons simply a hollow response on behalf of the elite, or was real concern for the dead sometimes a motivation for this activity (e.g. Kemp Reference Kemp2012, 232; Stevens Reference Stevens2006, 294; Reference Stevens2015, 82, fn 1)? It has long been observed that the large open spaces within the city's temples would seem suited to crowds gathering during festivals and celebrations for the god (Kemp & Garfi Reference Kemp and Garfi1993, 54–5, 61) and it is not far-fetched (if not directly provable) to suggest that they did so in the context of remembering ancestors.

The view from the non-elite cemeteries as regards belief frameworks is a multifaceted one, as a landscape-oriented approach illustrates. Interment of the non-elite dead in the eastern mountain, horizon of the Aten, potentially implied that they were in the company of the god. Yet there is no clear sense that funerary parties engaged with symbolic frameworks in positioning the dead. A study of burial orientation at the South Tombs Cemetery (also Kemp Reference Kemp, Hawass and Richards2007, using early excavation results), where we have the largest exposures of graves, suggests that local topography was a leading influence, but with little obvious symbolic meaning (Fig. 16). Graves cut into flat ground tend to follow the line of the wadi, a natural directional prompt, but when cut into sloping ground, along the wadi sides, they tend to run across the slope, the head of the deceased usually placed upslope. The possibility that the dead were being laid down as though in sleep, as in the elite tombs, is one that should not be overlooked. There is little indication, however, that funerary parties referenced the local ‘horizon’ at the end of the wadi or cardinal east/west. At this distance, it is impossible to understand fully how the eastern horizon of Akhetaten was conceived and exploited for its symbolic potential; it is worth noting the double-peaked stela (obj. 39446: Fig. 7), recalling the hieroglyph for ‘horizon’. The question can be asked, though, whether greater engagement with the movement of the sun in positioning the dead might be expected if this landscape was presented to the population, and/or engaged by them, as a symbolically meaningful one?

Figure 16. Grave orientation at the Lower Site (South Tombs Cemetery). The circles containing individual numbers are at the head end, where known. The correlation between topography and orientation is clearest here, where ground slope is quite marked, but the general trend can be detected across the site (see Figure 14).

Further insight on belief frameworks is found in the artefact record. Amongst the decorated coffins there are examples in a style that continues pre-Amarna period coffin iconography, showing traditional funerary deities and texts assimilating the deceased with Osiris, but also a new ‘godless’ style (Bettum Reference Bettum2015). A rethink as regards coffin decoration was clearly under way—although the retention of traditional iconography is a potentially important indicator of religious freedom at the city (Stevens forthcoming). The use of pointed imagery for stelae and other grave markers (Fig. 17) also suggests engagement with solar cult, the pyramid an ancient solar symbol thought to mimic the rays of the sun. Not widely used in the artistic repertoire of the Amarna period, it was nonetheless well suited to the iconography of the Aten (Fig. 17). The use of pyramidal superstructures prompts the question whether individuals were defining for themselves domains where they would be in the company of the Aten after death (Kemp et al. Reference Kemp, Stevens, Dabbs, Zabecki and Rose2013, 76).

Figure 17. A pottery ‘offering place’ (left, obj. 37853) and triangular motif on a child's coffin (lower right, obj. 40106) that recall tomb/tomb chapel/pyramid models. At top right, an ostracon with Aten image from the Workmen's Village (obj. 836), showing the overlap in iconography of the god and the triangle/pyramid. (Photographs: Gwil Owen (pottery model); Nicole Peters (coffin).)

The role of grave markers was also presumably to identify places where offerings could be left for the deceased. Yet one of the striking features of the cliff-side cemeteries is their distance from the riverside suburbs: it is just under 3 km from the Main City to the South Tombs Cemetery, for example (Fig. 1). This raises the question of how active these were as ritual landscapes after the funeral. Testing post-burial engagement is difficult because of the loss of surface remains. No trace has been found of structures to support events, although ritual feasts often utilized just tents, or mats on the ground (Green Reference Green, Knoppers and Hirsch2004, 210–12). There are hints that pottery vessels were sometimes left at the graveside, but the quantity of pottery from the South Tombs Cemetery is not particularly large and at the North Tombs Cemetery there is remarkably little so far (Pamela Rose pers. comm., 2016). This must raise some doubt over whether offerings were left in pottery vessels on any substantial scale after the funeral (we have few comparative assemblages: Harrington Reference Harrington2013, 90).

Overall, a model of fairly low-level post-burial engagement may be a reasonable fit with the surviving evidence. If the cemeteries were regularly visited spaces, we can also ask whether there would be more individualization and diversification amongst the graves, including in terms of status marking. The Workmen's Village offers one example of a landscape in which cemetery and settlement were more closely integrated and a more elaborate framework of ritual facilities developed at the private chapels, although the skilled nature of this community needs to be considered (Stevens Reference Stevens2015, 80–81); at the Stone Village, the second of the desert villages, there are no chapels of this kind. At the desert cemeteries, funerals could have provided opportunities to visit tombs of other family members, but there may otherwise have been little scope for casual encounters with these landscapes. It is appropriate to ask: how much time did people have in their everyday lives to trek out to the cliffs? For some individuals, who lived closer to cemeteries and family tombs before the Amarna period, this may well have diminished their experiences regarding commemoration of the deceased at the new city. We can only speculate on how far this may have been counteracted by celebrations at the city's temples, with public involvement in such events so difficult to measure.

Conclusion

The short-lived nature of Akhetaten provides a unique opportunity to build reflexive interpretations across settlement and cemetery space. Preliminary work indicates both continuity and a sense of disjunction in this respect, the latter most acutely visible at the North Tombs Cemetery, while differences in life experiences and treatment of the dead are also appearing across the burial grounds. Just as social analysis, including the pursuit of urban sub-communities, is difficult via housing data beyond economic co-dependence, it remains elusive within the burial record. Partly due to the loss of data over time, and the modest nature of the burials, the muting of expressions of personal and socio-economic differences is itself nonetheless one of a series of transformations in social presentation from life to death that require further elucidation.

The North Tombs Cemetery, both in its burial record and size, containing almost as many interments as the South Tombs Cemetery, offers a reminder of how unrepresentative the surviving ground plan of Akhetaten is of the city's broader urban environment, if the latter is taken to include settlements for labourers and agricultural communities. The house-size chart (Fig. 3) is likewise relevant to only a limited portion of Amarna society: those living in mud-brick houses in the core city, who seem to have been largely involved in manufacturing goods (e.g. Kemp & Stevens Reference Kemp and Stevens2010) and in the running of the city itself. To represent the urban landscape more widely, even if just to incorporate east-bank labourers’ settlement/s, we need to imagine the chart extending considerably to the left, and presumably incorporating living spaces that did not have the typical character of houses.

At Akhetaten, the notion of an ideal burial in a rock-cut tomb was a leading factor in dictating the choice of burial landscape for officials, and inadvertently for the non-elite, most of whom were assembled into large public burial grounds nearby. Overarching organization of the non-elite dead may be a signature of larger settlements, which needed planned responses to the disposal of large numbers of dead, and it is probably detectable at Amarna because we are viewing the cemeteries so close to their time of origin. City-level organization of the non-elite dead need not, however, have been accompanied by any particular concern for their welfare or brought much advantage for the population, especially if they did not view the setting of the cliff-side cemeteries as spiritually significant.

The people of Amarna nonetheless retained a role in shaping the city's burial grounds, especially at an internal level: further evidence, in a way, that urban services in pre-modern cities developed often from individual and community agency (Smith et al. Reference Smith, Dennehy, Kamp-Whittaker, Stanley, Stark and York2016). At the South Tombs Cemetery, families were probably the main agents in creating the burial landscape, and local communities likewise at the desert villages. The North Tombs Cemetery, in contrast, cautions against reading pit-grave cemeteries as necessarily self-organized, its multiple burials probably reflecting something other than family-level interment of the dead. Someone was preparing these bodies for burial—wrapping them and sometimes providing simple burial goods—but if the dead were (re)integrated into family and community environments during this process, it has not obviously carried over to their permanent incorporation into family units after death. Urban inequality may be reflected here in the degree to which individuals are separated from family environments during the transition from death to burial, tied to peripheral living environments.

Multivalent lines of evidence suggest that the living and dead interacted across varying platforms at Akhetaten—in the home, cemeteries and, for at least some, in the city's temples—although the importance of each remains to be more fully elucidated. With the cliffs set back so far from the river, and little archaeological evidence to date for post-funeral rituals, contact with the non-elite necropoles may have been relatively limited. The excavations underscore the need for more work on informal burial grounds to rebalance our understanding of mortuary ritual based on formal tombs. Notions that the tomb retained central importance after the funeral as a place for making offerings (e.g. Meskell Reference Meskell2002, 203) and that the deceased in the New Kingdom were buried with their head westwards to face the rising sun (Assmann Reference Assmann2005, 317–24) are not easily transferrable to Amarna's non-elite cemeteries.

As regards spiritual responses to death and burial, while the cemeteries, and Amarna generally, offer a somewhat disjointed body of evidence, it is not necessary to force this into a neat narrative. The evidence could fit a population that is, to a considerable extent, left on its own to navigate a new city and the physical and spiritual changes it presented to them, remembering that we are looking only at the first 15 years of the city's history. The work prompts a central question as regards the character of Akhetaten: did its population have a sense of collective social identity? Place of origin was an important factor in constructing and conveying personal identity in ancient Egypt. The elite show a strong sense of attachment to home-town in choosing their burial place, particularly lower-ranking officials, under less obligation to the capital (Auenmüller Reference Auenmüller, Dębowska-Ludwin, Jucha and Kołodziejczyk2014), and it is conceivable that repeated use of burial grounds helped form community identity more widely, perhaps most apparent when away from home. While collective memory itself was probably short-lived (Meskell Reference Meskell, Van Dyke and Alcock2003, 37), thousands of people consecutively faced severed ties to traditional burial grounds during the initial settlement of Akhetaten, where there was evidently little chance of repatriation upon death for most. Allegiance to a local god, however, offered another means of constructing and conveying identity, especially from the New Kingdom, when such figures were also increasingly invoked as benefactors of burial (Assmann Reference Assmann2002, 232–3). While it is Akhenaten who has been placed in the latter role at Akhetaten (Assmann Reference Assmann2002, 232), the king is largely absent from the iconography preserved at the non-elite burial grounds. The scattered solar imagery that is instead emerging here could suggest a milieu in which the Aten was beginning to develop an early and direct following as a true city god, spurred by personal concerns for the dead; a hint of emerging civic identity at Akhetaten from within a short-lived urban community that would soon face the further upheaval of the city's demise.

Akhetaten stands as an ancient world example of the antithesis of the modern city, the latter defined partly by its infrastructure that serves (and increasingly shapes) its human occupants, who remain barely aware of its existence (Amin & Thrift Reference Amin and Thrift2017). At Akhetaten, it was the people who were the infrastructure, of a city that only barely took them into account. They retained, nonetheless, degrees of agency in the treatment of their dead, which in turn formed one basis of differentiation of people's experiences across, and of, their urban environment. How far this was unique to Akhetaten as a rapidly built cult arena, or was typical of Egyptian cities more broadly, is a question that remains.

Acknowledgements

The cemetery study has been generously supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities (grant no. RZ-51672-14), British Academy (grant no. SG121253), National Geographic, King Fahd Center for Middle East Studies (University of Arkansas), USAID (American Research Center in Egypt), McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Amarna Research Foundation, Aurelius Trust, Thriplow Trust, Amarna Trust, Institute for Bioarchaeology, Pasold Research Fund and public donations. Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed here do not necessarily represent those of the National Endowment for the Humanities.

The fieldwork is possible through the support of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities. For their comments on drafts of this paper, I am indebted to Gretchen Dabbs, Jerry Rose, Anders Bettum, Pamela Rose, Alan Clapham, Johanna Petkov and the CAJ reviewers and editors, and for discussions on the cemeteries to Mary Shepperson, Wendy Dolling, Melinda King Wetzel, Barry Kemp, Lucy Skinner and many others. Thanks are due to the international team who have retrieved, cared for and studied the burial remains, and especially to the bioarchaeological team headed by Jerry Rose and Gretchen Dabbs, whose work is integral to the discussion presented here. The cemetery study forms part of the Amarna Project directed by Barry Kemp, in collaboration with the University of Arkansas and Southern Illinois University. For information on supporting the Amarna Project, please visit www.amarnatrust.com.