Collective attitudes toward the appropriate roles of women and men in society—whether labeled “culture,” “norms,” “ideology,” or “public opinion”—constitute one of the primary explanations for women's exclusion from the traditionally masculine public sphere of the workforce, political power, and policy influence (see, for example, Paxton, Hughes, and Barnes Reference Paxton, Hughes and Barnes2021, 113–14). Yet, even a half-century after Rule Krauss (Reference Rule Krauss1974, 1719) called for more and better data on these collective attitudes, what we have available to us remains inadequate for fully examining their causes and consequences. In the decades since, national and cross-national surveys have included a plethora of relevant questions, but sustained focus has been scant and the variety of these survey items renders the resulting data incomparable. As a consequence, cross-national research has been constrained to studying countries at just one or a few time points (see, for example, Alexander Reference Alexander2012; Glas and Alexander Reference Glas and Alexander2020; Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003) or to relying on proxies, such as predominant religion or the percentage of women in office (see, for example, Barnes and O'Brien Reference Barnes and O'Brien2018; Burns, Schlozman, and Verba Reference Burns, Schlozman and Verba2001, 340–1; Claveria Reference Claveria2014). Cross-national and longitudinal investigation of, for example, the argument that such “attitudes influence both the supply of, and demand for, female candidates” has remained persistently a topic for future research (Paxton, Hughes, and Painter Reference Paxton, Hughes and Painter2010, 47).

In this letter, we present the Public Gender Egalitarianism (PGE) dataset, which is based on the host of national and cross-national survey data available and recent advances in latent-variable modeling of public opinion that allow us to make use of these sparse and incomparable data. It provides comparable estimates of the public's attitudes on gender equality in the public sphere of politics and paid work across countries and over time. We show that these PGE scores are strongly correlated with responses to single survey items, as well as with measures of women's participation in the workforce and in the boardroom. We expect that the PGE data will become an invaluable source for broadly cross-national and longitudinal research on the causes and effects of collective attitudes toward gender equality in the public sphere.

Examining the Source Data on Public Gender Egalitarianism

National and cross-national surveys have often included questions tapping attitudes toward equality for women and men in the public sphere over the past half-century, but the resulting data are both sparse, that is, unavailable for many countries and years, and incomparable, as they are generated by many different survey items. In all, we identified 51 such survey items that were asked in no fewer than five country-years in countries surveyed at least twice; these items were drawn from 123 different survey datasets.Footnote 1 Together, the survey items in the source data were asked in 126 different countries in at least two time points over 50 years, from 1972 to 2022, yielding a total of 3,036 country-year-item observations. Observations for every year in each country surveyed would number 6,300, and a complete set of country-year-items would encompass 321,300 observations. Compared to this complete set of country-year-items, the available data can be seen to be very, very sparse. From a more optimistic standpoint, we note that there are 1,301 country-years in which we have at least some information about the public gender egalitarianism of the population, that is, some 46 per cent of the 2,825 country-years spanned by the data we collected. However, there can be no denying Claveria's (Reference Claveria2014) observation that the many different survey items employed renders these data incomparable and difficult to use together.

Consider the most frequently asked item in these data, which asks respondents whether they strongly agree, agree, disagree, or strongly disagree with the statement: “On the whole, men make better political leaders than women do.” Employed by the Americas Barometer, the Arab Barometer, the Eurobarometer, the Latinobarómetro, the Pew Research Center, and the European Values Survey (EVS), and the World Values Survey (WVS), this question was asked in a total of 455 different country-years. That this constitutes only 16 per cent of the country-years spanned by our data—and it should be remembered that this is the most common survey item—again underscores just how sparse the available public opinion data are on this topic.

The upper-left panel of Figure 1 shows the dozen countries with the highest count of country-year-item observations. The United States, with 177 observations, is far and away the best represented country in the source data, followed by Germany, Sweden, Poland, and South Korea. At the other end of the spectrum, three countries—Cambodia, Sri Lanka, and Suriname—have only the minimum two observations required to be included in the source dataset at all. The upper-right panel shows the twelve countries with the most years observed; this group is similar, though with Czechia and Italy joining the list and Japan and Australia dropping off. The bottom panel counts the countries observed in each year and reveals just how few relevant survey items were asked before 1990. Country coverage reached its peak in 2008, when respondents in seventy-eight countries were asked items about gender egalitarianism in the public sphere. In the next section, we describe how we are able to make use of all of these sparse and incomparable survey data to generate complete, comparable time-series PGE scores using a latent-variable model.

Fig. 1. Countries and years with the most observations in the PGE source data.

Estimating Public Gender Egalitarianism

There has been a recent blossoming of scholarship developing latent-variable models of public opinion based on cross-national survey data (see Caughey, O'Grady, and Warshaw Reference Caughey, O'Grady and Warshaw2019; Claassen Reference Claassen2019; Kolczynska et al. Reference Kolczynska2020; McGann, Dellepiane-Avellaneda, and Bartle Reference McGann, Dellepiane-Avellaneda and Bartle2019). To estimate public gender egalitarianism across countries and over time, we draw on the latest of these methods that is appropriate for data that are not only incomparable, but also sparse: the Dynamic Comparative Public Opinion (DCPO) model presented by Solt (Reference Solt2020b). The DCPO model is a population-level two-parameter ordinal logistic item response theory (IRT) model with country-specific item-bias terms (for a detailed description of the DCPO model, see Appendix C in the Online Supplementary Material and Solt [2020b, 3–8]). Here, we focus on how it deals with the principal issues raised by our source data: incomparability and sparsity.

The DCPO model accounts for the incomparability of different survey questions with two parameters. First, it incorporates the difficulty of each question's responses, that is, how much public gender egalitarianism is indicated by a given response. That each response evinces more or less of our latent trait is most easily seen with regard to the ordinal responses to the same question: strongly agreeing with the statement “both the husband and wife should contribute to household income” exhibits more public gender egalitarianism than responding “agree,” which, in turn, is more egalitarian than responding “disagree,” which is a more egalitarian response than “strongly disagree.” However, this is also true across questions. For example, strongly disagreeing that, “on the whole, men make better business executives than women do” likely expresses even more egalitarianism than strongly agreeing merely that both spouses should have paying jobs. Secondly, the DCPO model accounts for each question's dispersion, that is, its noisiness with regard to our latent trait. The lower a question's dispersion, the better that changes in responses to the question map onto changes in public gender egalitarianism. Together, the model's difficulty and dispersion estimates work to generate comparable estimates of the latent variable of public gender egalitarianism from the available but incomparable source data.

To address the sparsity of the source data—the fact that there are gaps in the time series of each country, and even that many observed country-years have only one or few observed items—DCPO uses local-level dynamic linear models, that is, random-walk priors, for each country. That is to say, within each country, each year's value of public gender egalitarianism is modeled as the previous year's estimate plus a random shock. These dynamic models smooth the estimates of public gender egalitarianism over time and allow estimation even in years for which little or no survey data are available, albeit at the expense of greater measurement uncertainty.

We estimated the model on our source data using the DCPO package for R (Solt Reference Solt2020a), running four chains for 4,000 iterations each, discarding the first half as warm-up and thinning the remainder by eight, which left us with 1,000 samples. The ![]() $\hat{R}$ diagnostic had a maximum value of 1.02, indicating the model converged.

$\hat{R}$ diagnostic had a maximum value of 1.02, indicating the model converged.

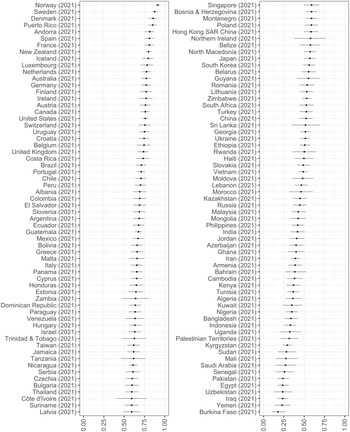

The dispersion parameters of the survey items indicate that all of them load well on the latent variable (see Appendix A in the Online Supplementary Material). The result is estimates of mean public gender egalitarianism, what we call PGE scores, in all 6,200 country-years spanned by the source data. Figure 2 displays the most recent available PGE score for each of the 124 countries and territories in the dataset.

Fig. 2. PGE scores, most recent available year.

Note: Gray whiskers represent 80 per cent credible intervals.

The Scandinavian countries and France are at the top of this list, along with Puerto Rico, which has had women of both of its major parties serve as chief executive and had a woman from each party holding the two most prominent elected offices on the island as recently as 2020. The latest scores for Burkina Faso, Yemen, Iraq, Uzbekistan, and Egypt have them as the places where public opinion is least favorable to gender equality in the public sphere.

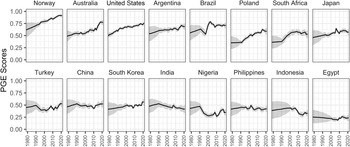

Figure 3 displays how PGE scores have changed over time in sixteen countries. Like Figure 2, it underscores the geographic breadth of the PGE dataset, which allows the study of countries and regions too often neglected in political science research (see Wilson and Knutsen Reference Wilson and Knutsen2022). Figure 3 also shows that while public opinion favoring gender equality in the public sphere has risen steadily in some countries, such as Norway and Australia, attitudes have changed little over time in others, like South Korea and the Philippines, or have fallen in some, as in Indonesia. They have even advanced and retreated, as in Brazil, or have declined and recovered, as in Nigeria. There is much to do to explain the causes and consequences of these trends in public gender egalitarianism.

Fig. 3. PGE scores over time within selected countries.

Notes: Countries are ordered by their PGE scores in their most recent available year. Gray shading represents 80 per cent credible intervals.

Validating PGE Scores

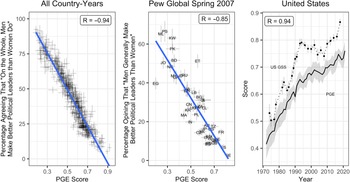

Such future research, however, depends on the validity of the PGE scores. Like Caughey, O'Grady, and Warshaw (Reference Caughey, O'Grady and Warshaw2019, 684–5), we provide evidence of our measure's validity with convergent validation and construct validation. Convergent validation refers to showing that a measure is empirically associated with alternative indicators of the same concept (Adcock and Collier Reference Adcock and Collier2001, 540). Here, we compare PGE scores to responses to individual source-data survey items that were used to generate our estimates, that is, we provide an “internal” validation test (see, for example, Caughey, O'Grady, and Warshaw Reference Caughey, O'Grady and Warshaw2019, 689; Solt Reference Solt2020b, 10). In the left panel of Figure 4, we examine the four-point question on political leaders mentioned earlier, which is the most common item in the source data across all country-years. Then, in the center panel, we look at the question that provides the most data-rich cross-section in the source data, which asked whether respondents felt “Men generally make better political leaders than women” and was included in Pew Global's spring 2007 survey. Finally, in the right panel, to evaluate how well the PGE scores capture change over time, we focus on the item with the largest number of observations for a single country in the source data, which asked respondents to the US General Social Survey whether they agreed or disagreed that “Most men are better suited emotionally for politics than are most women.” In every case, the correlations—estimated taking into account the uncertainty in the measures—are in the expected direction and very strong.

Fig. 4. Convergent validation: correlations between PGE scores and individual PGE source-data survey items.

Note: Gray whiskers represent 80 per cent credible intervals.

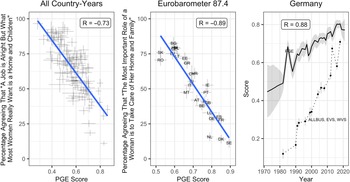

We continue, then, to construct validation, which refers to demonstrating for some other concept believed causally related to the concept a measure seeks to represent that the measure is empirically associated with measures of that other concept (Adcock and Collier Reference Adcock and Collier2001, 542). In Figure 5, we look to individual survey items not included in our source data, but tapping a related category of gender egalitarianism, namely, questions that ask how women should balance opportunities in the public sphere with their traditional duties in the private sphere. Assuming that attitudes that women should prioritize housework and childcare over paid employment and politics—or convictions that there will be negative consequences if they do not—will lead to less gender egalitarian opinions with regard to these latter, public-sphere activities, evidence for this theoretical relationship will provide construct validation for the PGE scores. Exemplars of such items across all available country-years (“A job is alright but what most women really want is a home and children” from the WVS and EVS), in cross-section (“The most important role of a woman is to take care of her home and family” from the Eurobarometer 87.4), and in time series (“A pre-school child is likely to suffer if his or her mother works” from the German ALLBUS, WVS, and EVS) all show strong correlations with the PGE scores.

Fig. 5. Construct validation: correlations between PGE scores and individual “balancing” gender egalitarianism survey items.

Note: Gray whiskers and shading represent 80 per cent credible intervals.

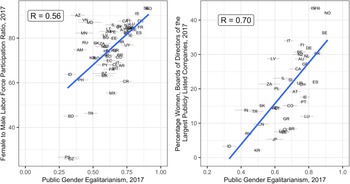

Finally, Figure 6 shows additional tests of construct validation. As attitudes toward gender egalitarianism in the public sphere plausibly both cause and are caused by women's gains in the workplace, strong relationships between the PGE scores and measures of workplace gender equality provide construct validation for our measure. In the left panel of Figure 6, we compare the PGE scores to the ratio of women's to men's labor force participation rates in 68 countries in 2017, drawing on data compiled by the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Statistics Division (2020). In the right panel, we plot the PGE scores against the percentage of women on the boards of directors of the largest publicly listed companies in 43 countries, also in 2017 (see OECD 2020). Both correlations are strong. Together, this evidence of construct validation and convergent validation attests to the validity of the PGE scores as measures of public opinion toward gender equality in the public sphere.

Fig. 6. Construct validation: correlations between PGE scores and indicators of workplace gender equality.

Note: Gray whiskers represent 80 per cent credible intervals.

Using the PGE Dataset

Version 1.0 of the PGE dataset includes PGE scores for 124 countries for as many years as possible from 1972 to the present, for a total of 2,787 country-years. It can be accessed in two ways: via a user-friendly web application on the PGE website, which plots scores for as many as four countries for easy comparison of levels and trends; and via the Harvard Dataverse, where the entire dataset is available for download for use in statistical analysis.

One aspect of latent-variable estimates of public opinion like the PGE dataset that is easy for researchers to overlook is the quantified uncertainty in the estimates. However, neglecting to incorporate this uncertainty by using only the mean estimate for each country-year in an analysis can lead one to mistakenly conclude that the analysis supports the hypothesis (see Tai, Hu, and Solt Reference Tai, Hu and Solt2022), as well as to mistakenly conclude that it does not support the hypothesis (see Crabtree and Fariss Reference Crabtree and Fariss2015). Therefore, taking the uncertainty in the PGE scores into account is crucial to reaching well-grounded conclusions. Step-by-step instructions for doing this via simulations, with examples, are included in the data download.

The PGE dataset will allow researchers not only to better address such long-standing questions as how collective attitudes on gender roles have influenced the election of women to national legislatures, and vice versa (see, for example, Alexander Reference Alexander2012; Paxton and Kunovich Reference Paxton and Kunovich2003), but also, for example, to pursue both new and more nuanced lines of inquiry on issues of policy responsiveness and policy feedback (see Busemeyer, Abrassart, and Nezi Reference Busemeyer, Abrassart and Nezi2021; Kittilson Reference Kittilson2008). We will revise and update the dataset as new survey data on public gender egalitarianism become available, and we look forward to a rapid growth in research that advances our understanding of the relationships between collective attitudes on gender roles and a wide range of other political phenomena.

Supplementary Material

Online appendices are available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123422000436

Data Availability Statement

Data replication sets for this article are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/T3UP6R

The most recent PGE dataset is available at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/WF3USY

This article's complete revision history is on Github at: http://github.com/fsolt/dcpo_gender_roles

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for helpful comments by DCPO Lab members Hyein Ko, Yuehong Cassandra Tai, and Yue Hu, as well as those received at the 2022 annual meeting of the Midwest Political Science Association.

Financial Support

None.

Competing Interests

None.