Gene-by-environment interactions have been a widely touted, but often difficult to replicate, concept in psychiatric genetics.Reference Karg, Burmeister, Shedden and Sen1 In particular, a considerable focus has been devoted to potential interactions between the serotonin transporter gene-linked polymorphic region (5-HTTLPR) and adverse life experience. A common 44-base pair insertion/deletion polymorphism in 5-HTTLPR is known to be involved in the reuptake of serotonin by the serotonin transporter in the brain through transcriptional efficiency of the long (L) and short (S) alleles.Reference Lesch, Bengel, Heils, Sabol, Greenberg and Petri2 The seminal report of a prospective longitudinal study by Caspi and colleaguesReference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig and Harrington3 showing S-allele carriers to be more vulnerable to depression upon exposure to environmental adversities was followed by many studies which varied in their success to replicate this finding.Reference Kendler, Kuhn, Vittum, Prescott and Riley4–Reference Covault, Tennen, Armeli, Conner, Herman and Cillessen6 Furthermore, several meta-analyses focusing on the interaction between 5-HTTLPR and environmental stress, with depression as the outcome variable, demonstrated inconclusive results.Reference Risch, Herrell and Lehner7, Reference Chaouloff8 Nevertheless, the diversity of studies and ongoing controversy have led to an increasing interest in stress-related biological pathways mediated by the serotonergic system in the development of psychopathology.

The hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis is one of most well-studied mechanisms through which 5-HTTLPR might interact with stressors.Reference Van der Doelen, Deschamps, D'Annibale, Peeters, Wevers and Zelena9 The serotonergic system has been suggested as ideally positioned to regulate glucocorticoid secretion via its ability to influence neural activity at the hypothalamic, pituitary and adrenal levels.Reference Chaouloff8 Based on the observations of altered HPA axis activity in a broad range of stress-related psychiatric disorders,Reference Dinan10 a number of studies have focused on the associations between the 5-HTTLPR genotype and HPA axis reactivity to acute stress.Reference Gotlib, Joormann, Minor and Hallmayer11–Reference Mueller, Armbruster, Moser, Canli, Lesch and Brocke18 Thus far, contradictory results have been found. Several studies demonstrated that being homozygous for the S allele in 5-HTTLPR is associated with an elevated cortisol response to psychosocial stress.Reference Gotlib, Joormann, Minor and Hallmayer11–Reference Dougherty, Klein, Congdon, Canli and Hayden13 However, other studies failed to support these initial findings,Reference Alexander, Kuepper, Schmitz, Osinsky, Kozyra and Hennig14–Reference Verschoor and Markus17 or even reported opposite results.Reference Mueller, Armbruster, Moser, Canli, Lesch and Brocke18 Recently, a meta-analysis (N = 1686) has been published in which the authors reported a statistically significant association of small effect between 5-HTTLPR genotype and HPA axis reactivity to acute psychosocial stress, with the SS variant demonstrating higher cortisol responses than the SL or LL variant of 5-HTTLPR.Reference Miller, Wankerl, Stalder, Kirschbaum and Alexander19 In addition, there is increasing evidence that the association between 5-HTTLPR and HPA axis reactivity is stronger when stressful environmental factors are taken into account.Reference Dougherty, Klein, Congdon, Canli and Hayden13, Reference Wüst, Kumsta, Treutlein, Frank, Entringer and Schulze16 Two previous studies with sufficient samples sizes (approximately N = 100) have suggested that the effects of 5-HTTLPR on cortisol reactivity are stronger in individuals with a history of stressful life events.Reference Alexander, Kuepper, Schmitz, Osinsky, Kozyra and Hennig14, Reference Mueller, Armbruster, Moser, Canli, Lesch and Brocke18

Taken together, the nature of the relationship between 5-HTTLPR and cortisol reactivity remains unresolved. Our primary goal was to assess whether cortisol reactivity to psychosocial stress varies as a function of 5-HTTLPR genotype, with a specific focus on women. In light of the previously demonstrated gender-dependent influences on HPA axis functioning, and considering the higher prevalence of stress-related disorders in women, our aim was to improve our understanding of the underlying physiological mechanisms of stress regulation in women as a function of mental health, and in particular personality pathology. In addition, we aimed to examine whether the magnitude of cortisol reactivity is modulated by an interaction between 5-HTTLPR genotype and childhood adversity. Although a certain degree of challenge during childhood may enhance lifelong coping skills,Reference Fergus and Zimmerman20 overwhelming early life stress has been strongly associated with an increased lifetime risk of psychopathology.Reference Heim and Nemeroff21 It is generally hypothesised that the major determinants of personality disorders are a combination of intrinsic biological vulnerabilities and early life exposure to traumatic experiences.Reference Fonagy and Bateman22 Our focus on personality pathology, particularly borderline personality disorder (BPD), was motivated on the basis that this sample would include clinically significant childhood trauma, thereby giving us the opportunity to evaluate a broader range of childhood maltreatment severities. Accordingly, we included both medication-free women recently diagnosed with personality disorder and demographically matched healthy controls.

Method

Participants

The study sample comprised 151 female participants of reproductive age (18–45 years). Women were self-referred in response to advertisements (n = 66) or recruited from mental health out-patient clinics (n = 85). Women with a diagnosis of personality disorder, cluster C personality disorder or BPD were classified into the psychopathology group for additional statistical analysis. Psychiatric diagnoses were obtained by Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR (2000) (SCID) for Axis I disorders.Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams23 Psychodiagnostic assessments were performed by a psychologist who underwent specialised training to perform SCID interviews. People were excluded from the study if they had a medical or comorbid diagnosis of bipolar disorder, schizophrenia or current major depression. The indicated exclusion criteria in the patient cohort were two-fold: (a) depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have all been reported to affect HPA axis activity, and (b) these disorders almost invariably involve treatment with psychotropic medications that have significant effects on HPA axis physiology. Notably, other comorbid Axis I disorders such as anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and eating disorders were eligible for participation in the study. Therefore, including participants with personality psychopathology with less severe Axis I symptoms provided us with the opportunity to evaluate the effect of a broad range of childhood trauma severities on the relationship between 5-HTTLPR genotype and cortisol responsivity.

Women screened for the control group were excluded on the basis of any DSM-IV Axis I or II diagnosis, or any history of psychiatric or psychological treatment. In addition, global exclusion criteria for both groups included current medication (with the exception of oral monophasic contraceptives containing a combination of ethinylestradiol and androgenic progestin), pregnancy, lactation, irregular menstrual cycle and body mass index (BMI) of <18 or >30. In addition, women were excluded on the basis of any prior diagnosis of endometriosis, polycystic ovary disease or gynaecological infection. Naturally cycling women were studied in the luteal phase of their menstrual cycle. Women using oral contraceptives were tested during the active pill weeks. The majority of the sample were of Dutch white Caucasian ethnicity (n = 139). Some women (n = 12) were of Netherlands Antilles heritage or mixed ethnicity.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was conducted according to the declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Medical Ethical Research Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam.

Procedure

Structured interviews were performed by telephone to confirm inclusion and exclusion criteria, after which participants were invited to the first session comprising the SCID interview.Reference First, Spitzer, Gibbon and Williams23 In addition, participants completed the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)Reference de Beurs and Zitman24 to evaluate psychological distress and the short form of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ)Reference Thombs, Bernstein, Lobbestael and Arntz25 to assess the severity of multiple forms of abuse and neglect.

The experimental session was scheduled during the second visit. Participants were asked to abstain from alcohol, nicotine, caffeine and intense physical activity for at least the prior 24 h. All measurements were performed between 14.00 and 16.00 h to minimise potential circadian influences on cortisol responses. After an acclimatisation period of 15 minutes, a baseline saliva sample was obtained. Subsequently, participants underwent the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST). Immediately following the TSST, additional saliva samples were obtained at +1, +15, +35 and +55 minutes. Participants were debriefed after the last saliva sample was collected.

Questionnaires

The BSIReference de Beurs and Zitman24 is a self-report questionnaire with 53 items on a four-point Likert scale and it assesses general psychological difficulties (total score) including somatisation, anxiety, depression and hostility (nine subscales). The BSI has adequate psychometric properties and good sensitivity to therapeutic changes.

The 28-item CTQ was used to assess the severity of multiple forms of abuse and neglect during childhood.Reference Thombs, Bernstein, Lobbestael and Arntz25 The CTQ has five domains: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect and emotional neglect. The total CTQ score was used as an index of childhood trauma.

The TSST

The TSST was administered according to the protocol of Kirschbaum and colleagues.Reference Kirschbaum, Pirke and Hellhammer26 Participants were informed about the procedure and asked to prepare a 5-minute speech (in which they would convince a panel of judges that they were a good candidate for their ideal job) while seated (anticipation period). Next, the two-member panel entered the room and participants were invited to stand and deliver their speech (public speaking task, PST). The PST was followed by a 5-minute mental arithmetic task (MAT). During the PST and the MAT, the panel monitored the participants' performance without offering verbal or non-verbal feedback, while maintaining an effectively neutral facial expression. Furthermore, the participants consented to audiovisual recording of the session and the camera and tripod were positioned prominently within the room, in direct view of the participant.

Cortisol assay

Saliva samples were collected using Sarstedt Cortisol Salivette® cotton swab collection tubes. Participants were asked to chew on the swabs for 2 minutes to stimulate saliva flow. Samples were stored at −20°C until analysis. The free salivary cortisol was measured using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Demeditec Diagnostics, Kiel, Germany, DES6611). The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were below 10 and 7%, respectively.

5-HTTLPR genotyping

DNA was isolated from the saliva collected with the Salivette® device using an adapted version of the Qiagen Buccal Brush DNA purification kit. Purified DNA was amplified by polymerase chain reaction, using the following primers: forward, 5′-TGCGGGGGAATACTGGTAGG-3′; reverse, 3′-GAACGTGGGAGGCAGCAGAC-5′. Amplified DNA was separated by electrophoresis using a 2% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide. Electrophoresis was performed at 120 V and 100 mA for 2 h. The 5-HTTLPR genotype was determined based on the relative height and number of DNA bands.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM, version 21). Results are expressed as mean ± s.e.m., unless otherwise specified. A priori power analysis yielded an estimate that a total sample of 159 participants for cortisol responsivity would be required for the detection of an interaction with Eta squared (η2) of ≥0.15 and power of 0.80, at a significance level of α = 0.05. Data per parameter were tested for normality of the distribution by visual inspection of quantile–quantile plots and Levene's tests for homogeneity of variance. To meet the normality assumption, cortisol data were logarithmically transformed. For descriptive purposes, the mean data shown in Fig. 1 and Table 2 are presented in original units. The Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was determined based on the total 5-HTTLPR sample (N = 151) using χ2-tests. Initial group comparisons between women with personality disorders and healthy controls were conducted using χ2-tests and analyses of variance (ANOVA). In subsequent analyses, main effects and interactions between the 5-HTTLPR genotype (bi-allelic genotype classification) and CTQ total scores on the cortisol stress response were assessed. The cortisol response to the TSST was computed by subtracting baseline cortisol from the peak value, 15 minutes after the stress test. In accordance with previous studies, we identified oral contraceptive use (non-users v. users) and personality psychopathology (healthy controls v. Cluster C personality disorder v. BPD) as variables associated with altered cortisol reactivity, and therefore these variables were included as fixed factors in the analyses. Additional analyses were performed controlling for age, BMI and ethnicity to ensure the results were robust. Greenhouse–Geisser corrections were applied where appropriate and adjusted results are reported. Effect sizes were calculated by partial η2. P-values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. Furthermore, ANOVAs were conducted across two subsamples of women with and without personality psychopathology. To control for the effects of the presence of PTSD and eating disorders on cortisol responses, the primary analyses were re-run to serially exclude each of these diagnostic groups individually.

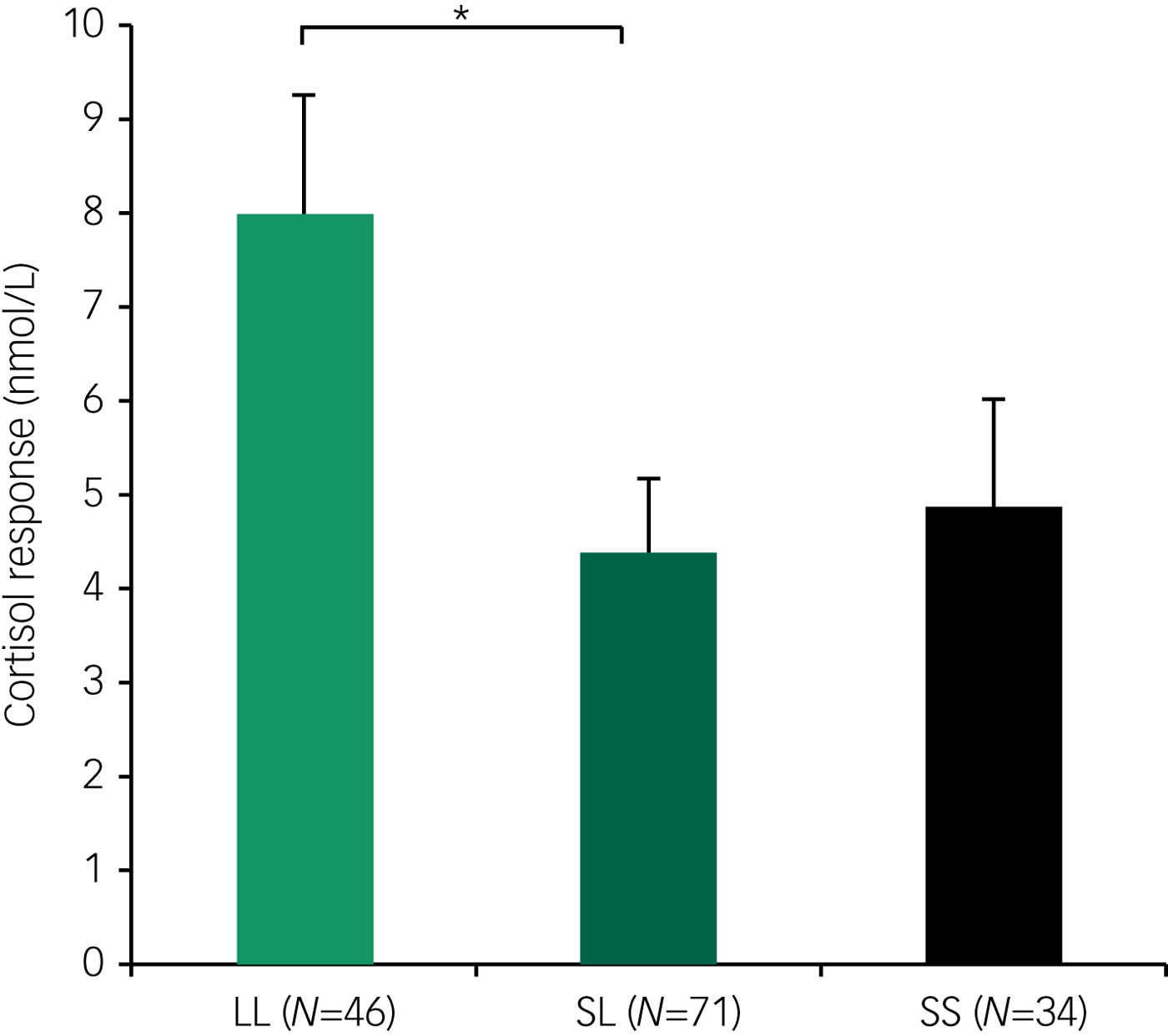

Fig. 1 Mean (±s.e.m.) salivary cortisol response to the Trier Social Stress Test (computed by subtracting the baseline measurement time point from the peak value 15 minutes post-stress) as a function of 5-HTTLPR genotype in female participants (* P < 0.05).

Results

Sample characteristics of the participants classified by 5-HTTLPR genotype are shown in Table 1. Participants were divided on the basis of a bi-allelic classification (SS, SL and LL). Genotype frequencies were consistent with the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium [χ2 (1) = 0.43; P = 0.51]. No differences were observed across 5-HTTLPR genotypic classes regarding age, BMI, ethnicity, oral contraceptive use, personality psychopathology, CTQ total score or psychological distress score (P ≥ 0.10; Table 1).

Table 1 Sample characteristics (mean, s.d.) categorised by 5-HTTLPR genotype

BMI, body mass index; CTQ, Childhood Trauma Questionnaire; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory.

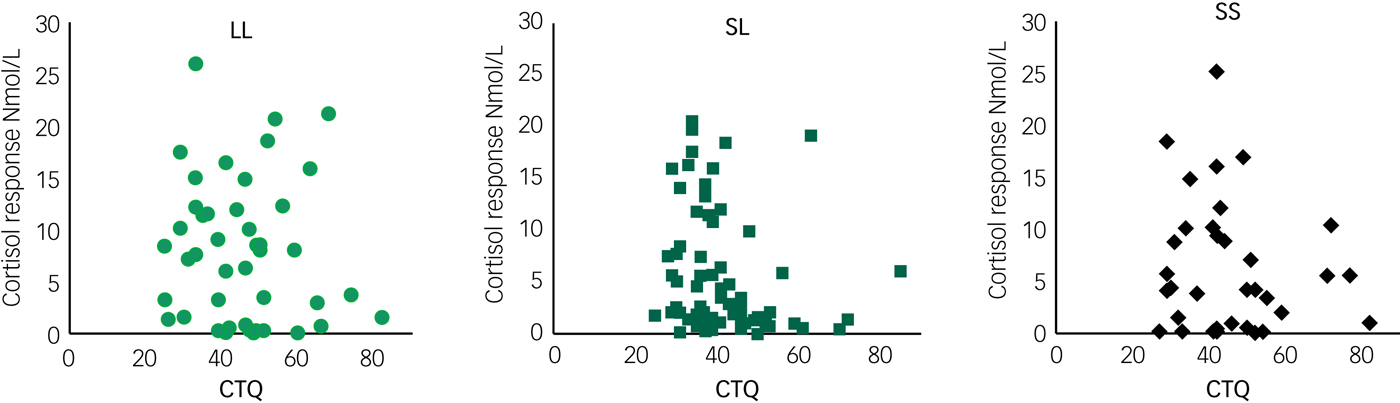

We found a significant effect of the 5-HTTLPR genotype on cortisol responsivity to the TSST [F(2, 142) = 3.46, P = 0.03, η2 = 0.05]. Specifically, LL allele carriers demonstrated the highest cortisol responsivity to psychosocial stress (post hoc pairwise analyses: LL > SL, P = 0.03; LL > SS, P = 0.07) (Fig. 1). Analysis of covariance revealed no significant influence of the CTQ score on cortisol responsivity to the TSST [F(1, 44) = 0.07, P = 0.80], nor was there a significant interaction of 5-HTTLPR with CTQ score [F(2, 142) = 0.66, P = 0.52] (Fig. 2). To further examine whether cortisol responsivity varied as a function of the interaction between 5-HTTLPR and CTQ score, we performed additional independent analyses in the patient and healthy control samples. Analyses of the interaction between 5-HTTLPR and CTQ score revealed no significant interactions of cortisol responsivity in either patients (P = 0.42) or controls (P = 0.33). The main effect of the 5-HTTLPR genotype remained significant when controlling for personality psychopathology and oral contraceptive use, as well as when age, BMI and psychological distress were included as covariates. In addition, no effect of ethnicity was found on cortisol responsivity to the TSST. Women with BPD showed significantly lower cortisol responses to the TSST [F(2, 141) = 3.28, P = 0.04, η2 = 0.05], which was considered a significant main effect of personality psychopathology. Moreover, we observed a significant main effect of oral contraceptives [F(1, 141) = 12.82, P < 0.0001, η2 = 0.08] as women using oral contraceptives had significantly lower cortisol responsivity to the TSST.

Fig. 2 Correlations between cortisol response and Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) total score. No significant associations were observed between cortisol response and CTQ for any 5-HTTLPR genotype. Analysis of covariance yielded no significant influence of the CTQ score on cortisol responsivity to the TSST [F(1, 44) = 0.07, P = 0.80], nor was there a significant interaction between 5-HTTLPR and CTQ score [F(2, 142) = 0.66, P = 0.52].

To ensure that the observed effects of 5-HTTLPR on cortisol response were not influenced by sample stratification regarding personality psychopathology or contraceptive use, the relationship between 5-HTTLPR genotype and cortisol responsivity to the TSST was examined independently for each oral contraception and psychopathology group. No significant differences were found within both the oral contraception and psychopathology groups (P ≥ 0.12) (Table 2). Additional ANOVA analyses were repeated, excluding (1) participants with PTSD and (2) participants with an eating disorder. These analyses further supported both the magnitude and direction of the effects observed for the total sample, suggesting that the results cannot be explained by either comorbid PTSD or eating disorders within our sample (PTSD: F(2, 140) = 2.34, P = 0.19; eating disorder: F(2, 129) = 2.74, P = 0.21).

Table 2 Mean salivary cortisol response to the Trier Social Stress Test in each psychopathology and oral contraceptive group by 5-HTTLPR genotype

HC, healthy controls; BPD, borderline personality disorder.

Discussion

The results of our study demonstrated that 5-HTTLPR genotype is significantly associated with cortisol responsivity to psychosocial stress in women. In particular, women with the LL genotype exhibited significantly higher free salivary cortisol responses to the TSST compared with women carrying at least one S allele. Furthermore, the association of the 5-HTTLPR genotype with cortisol responsivity was not moderated by the burden of early life adversity, as quantified by the CTQ.

Although our results are in line with those of Mueller et al,Reference Mueller, Armbruster, Moser, Canli, Lesch and Brocke18 they are difficult to reconcile with other studies.Reference Gotlib, Joormann, Minor and Hallmayer11–Reference Verschoor and Markus17 However, gender-based influences might be one of the important factors mediating this distinction because most studies have not been designed to specifically address gender-based differences. Two earlier studies observed that cortisol responsivity to stress was particularly enhanced in female homozygous S allele carriers.Reference Gotlib, Joormann, Minor and Hallmayer11, Reference Jabbi, Korf, Kema, Hartman, van der Pompe and Minderaa27 In contrast, we observed a significant association in the opposite direction. Several reasons might be responsible for the differences between earlier studies and our study. First, there are notable differences in age. The majority of previous studies investigated particularly young cohorts, including newborns and adolescents;Reference Gotlib, Joormann, Minor and Hallmayer11, Reference Dougherty, Klein, Congdon, Canli and Hayden13–Reference Bouma, Riese, Nederhof, Ormel and Oldehinkel15, Reference Verschoor and Markus17 whereas our study included adult females with a mean age of 28 years, in a period of reproductive hormonal cycling that is highly distinct from children and young adolescents. A broad range of behaviours and effects on physiological systems are highly influenced by ovarian steroid functioning.Reference Ebner, Kamin, Diaz, Cohen and MacDonald28 In addition to the well-known effects of the menstrual cycle on HPA axis activity, several studies have suggested that ovarian steroids exert a strong influence on the serotonergic system.Reference Hiroi, McDevitt and Neumaier29, Reference Lu, Eshleman, Janowsky and Bethea30 Therefore, the modulating effect of 5-HTTLPR on the cortisol response to stress might be different across qualitatively distinct, reproductive-age cohorts. Accordingly, age accounts for a substantial proportion of the variance across 5-HTTLPR genetic association studies of depression.Reference Uher and McGuffin31

The influence of hormonal contraceptives containing ethinylestradiol should also be noted. Considering that the majority of women during their reproductive age rely upon hormonal contraceptives, we ensured that we were adequately powered to examine the influence of oral contraceptives. Our inclusion criteria required that oral contraceptives contained the most commonly used preparation of ethinylestradiol in combination with androgenic progestins. Cortisol responsivity was significantly attenuated in women using oral contraceptives. This finding is consistent with the well-established oestradiol-induced increase in corticosteroid-binding globulin levels, thereby enhancing the buffering capacity of serum cortisol with a reduction of free cortisol availability.Reference Vange van der, Blankenstein and Koosterboer32 However, oral contraceptive use did not alter the association between 5-HTTLPR genotype and cortisol responsivity to the TSST. For future studies, an even greater emphasis on endogenous and exogenous hormones is needed to identify the underlying mechanisms by which hormonal status influences HPA axis functioning in women and the corresponding relationship to the serotonergic system.

More than half of the women included in our study were diagnosed with a personality disorder and seeking out-patient psychological treatment. Although our sample has notable distinctions from the majority of previously investigated samples, some of the clinical features such as stress vulnerability are comparable to previous samples at high risk for depression.Reference Gotlib, Joormann, Minor and Hallmayer11, Reference Jabbi, Korf, Kema, Hartman, van der Pompe and Minderaa27 Indeed, we observed that altered HPA axis reactivity to stress was associated with personality psychopathology. Although the inclusion of women with personality disorder provided us with an opportunity to examine a wide range of childhood trauma severities, we acknowledge that evaluation of women with personality psychopathology likely complicates the interpretation of the direct relationship between 5-HTTLPR genotype and cortisol reactivity. It has previously been suggested that psychopathological state affects both the HPA axis and the serotonergic system.Reference Caspi, Sugden, Moffitt, Taylor, Craig and Harrington3, Reference Hankin, Barrocas, Jenness, Oppenheimer, Badanes and Abela33, Reference Nater, Bohus, Abbruzzese, Ditzen, Gaab and Kleindienst34 Nevertheless, when controlling for personality psychopathology, the main effect of 5-HTTLPR genotype on the cortisol response to the TSST was unchanged.

Regarding childhood trauma, our study conflicts with two earlier studies demonstrating that 5-HTTLPR genotype interacts with stressful life events in the cortisol response to psychosocial stress.Reference Alexander, Kuepper, Schmitz, Osinsky, Kozyra and Hennig14, Reference Mueller, Armbruster, Moser, Canli, Lesch and Brocke18 However, it is important to note that the operational definition of adverse life events was somewhat different in our study than in these two previous studies. Alexander et al Reference Alexander, Kuepper, Schmitz, Osinsky, Kozyra and Hennig14 demonstrated that homozygous S allele carriers had significantly higher cortisol responsivity, but this was only observed in people with a high burden of stressful life events. Mueller et al Reference Mueller, Armbruster, Moser, Canli, Lesch and Brocke18 demonstrated that individuals carrying the LL allele showed a higher cortisol response to stress than S allele carriers, but this pattern was reversed when individuals were exposed to three or more stressful life events during the first 5 years of life. Our findings highlight the lack of a significant interaction between 5-HTTLPR genotype and burden of early life events on the cortisol response to psychosocial stress.

We employed the CTQ scale for the assessment of early life adversity.Reference de Beurs and Zitman24 The CTQ is a retrospective self-report inventory, intended to measure childhood abuse or neglect during the first 15 years of life. Therefore, it is plausible that retrospective recollection and/or reporting biases of early adversities, most notably regarding the nature of the event and the neurodevelopmental period when the event occurred, might be a source of inconsistent findings. Unfortunately, we were not able to divide the CTQ score into more specific lifetime periods, nor to define whether the traumatic events were incidental or chronic. In addition, retrospective methods of assessment might result in impaired accuracy of answers due to recall bias. Nevertheless, good correlations have been reported between CTQ scores and clinician ratings obtained by semi-structured interviews.Reference de Beurs and Zitman24 Furthermore, it has been suggested that sexual abuse and the 5-HTTLPR genotype have stronger effects on depressive symptoms than other forms of maltreatment.Reference Aguilera, Arias, Wichers, Barrantes-Vidal, Moya and Villa35 Therefore, subtypes of maltreatment may interact more specifically with genetic factors on HPA axis functioning and the aetiology of stress-related disorders. In addition, stressful events occurring in childhood have been shown to be more consistently associated with neurobiological changes than those limited to adulthood.Reference Sibille and Lewis36, Reference Kobiella, Reimold, Ulshöfer, Ikonomidou, Vollmert and Vollstädt-Klein37 Adversities in early childhood, compared with those limited to adulthood, have been demonstrated to interact with 5-HTTLPR as a predictor of clinical depression.Reference Karg, Burmeister, Shedden and Sen1 However, a recently published collaborative meta-analysis casts doubt upon the effect size of any putative interaction between life stress and 5-HTTLPR genotype on increased risk of depression.Reference Culverhouse, Saccone, Horton, Ma, Anstey and Banaschewski38

The TSST has repeatedly been shown to be a reliable tool for eliciting robust endocrine and cardiovascular responses in the vast majority of participants.Reference Dickerson and Kemeny39 Notably, some studies that used modified TSST protocols (e.g. by leaving out the presence of an evaluative audience) failed to observed an association between the 5-HTTLPR genotype and cortisol reactivity, suggesting the particular importance of the psychosocial stressor.Reference Alexander, Kuepper, Schmitz, Osinsky, Kozyra and Hennig14, Reference Bouma, Riese, Nederhof, Ormel and Oldehinkel15 However, several studies have demonstrated a significant impact of 5-HTTLPR on cortisol response to a mild stressor in psychologically vulnerable participants, which might suggest different relationships between genetic determinants and specific physiological and psychological processes.Reference Gotlib, Joormann, Minor and Hallmayer11, Reference Jabbi, Korf, Kema, Hartman, van der Pompe and Minderaa27

Several limitations should be taken into account when evaluating our findings. We did not consider modulatory polymorphisms of the L allele, designated as LA and LG, which have been reported to provide different levels of transporter expression.Reference Nakamura, Ueno, Sano and Tanabe40 The LG and S allele were demonstrated to have a similarly lower serotonin transporter expression compared with the LA allele.Reference Nakamura, Ueno, Sano and Tanabe40 However, other studies found no significant differences between classifications based on inferred levels of transporter expression.Reference Gotlib, Joormann, Minor and Hallmayer11, Reference Wüst, Kumsta, Treutlein, Frank, Entringer and Schulze16 Moreover, given that our study was focused specifically on women, it remains unknown to what extent these findings might extend to men. Our sample was also characterised by a limited ethnic heterogeneity; however, although women were primarily Dutch white Caucasian (92.1%), no significant differences were observed in the distribution of genotypes among ethnic groups. Although we enrolled a considerable sample of women (n = 151), it should be noted that the statistical power of our analyses was still relatively limited and should be regarded as exploratory.

Future studies are needed to clarify the potential contribution of biological and environmental factors to the HPA axis reactivity to stress, alongside the influence of 5-HTTLPR allelic variation.

Funding

This study was funded by internal resources of the Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam and Mental Health Clinic, Riagg Rijnmond. The Erasmus University Medical Center Rotterdam and Riagg Rijnmond had no role in the design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.