LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand the guidance on fitness to be interviewed in Code C of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE)

• comprehend the framework and factors to consider when assessing an individual's fitness to be interviewed

• appreciate some of the practical issues involved when completing this assessment in an in-patient setting.

When the police interview someone suspected of committing a criminal offence, it is important that the interview evidence is reliable, to help prevent a miscarriage of justice (Gudjonsson Reference Gudjonsson1995; Green Reference Green, Shenoy and Kent2012). To this end, the police may request an assessment of the suspect's fitness to be interviewed if there are concerns that they are vulnerable because of a mental health condition or mental disorder that may impair the reliability of their evidence or may cause them to come to harm through the interview process.

Clarity as to the purpose of the assessment is important. This is because the police sometimes ask for a ‘capacity assessment’ and also have in mind the patient's fitness to plead and stand trial or their mental state at the material time and appear to think that, if the patient is unfit to plead and stand trial or has a mental condition defence, this is a reason for not proceeding with the investigation. It is often necessary to point out that these are separate considerations that should be addressed later in the investigatory process, as (a) they are offence specific and (b) they require expert opinion that is independent of the team providing care for the patient. It is not uncommon, when a potential crime is reported to the police, for an inexperienced police officer to say that there is no point in investigating the case or interviewing witnesses or the suspect because ‘they will get off with insanity’ or ‘they won't be fit to plead’ or even to suggest that there is no point in charging someone who is already detained under mental health legislation. It is therefore also necessary in some cases to explain how the enhanced measures for public protection, available in the form of a restriction order, whether on a finding of unfitness to plead or on a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity or on conviction where there is a risk of serious harm to the public, can only be deployed if the person is charged with a criminal offence. In some cases it may be necessary, in the statement as to the individual's fitness to be interviewed, to include a sentence to this effect:

‘For the avoidance of doubt, this is an opinion as to X's fitness to be interviewed. Issues such as fitness to plead and stand trial and possible mental condition defences are separate issues which will be influenced by the nature of the offence(s) charged and opinions on these issues must be sought from independent experts. It is considered unethical, other than in exceptional circumstances, for the treating psychiatrist to give an opinion on such issues.’

Most of the current UK guidance for assessing fitness to be interviewed is given in the context of police station interviews. However, with 46 107 reported assaults on National Health Service (NHS) staff members within mental health services during the 12 month period ending March 2016 (NHS Protect 2016) and numerous patient-on-patient assaults, the police are sometimes requesting these assessments and conducting their interviews while individuals are on in-patient psychiatric wards. Although we are not aware of any statistics, we have no reason to believe that this is any less of a problem in independent hospitals that provide mental healthcare.

The lack of training and guidance in assessing fitness to be interviewed was highlighted in the late 1990s by Protheroe & Roney (Reference Protheroe and Roney1996). Since then, detailed guidance has been produced for forensic physicians (Norfolk Reference Norfolk2001; Stark Reference Stark, Rix and Stark2020) and psychiatrists (Rix Reference Rix1997, Reference Rix2011; Rix et al Reference Rix, Mynors-Wallis and Craven2020, Ventress Reference Ventress, Rix and Kent2008). However, there has not been any specific guidance tailored to the assessment of fitness to be interviewed and its practicalities in the context of adult mental health in-patient settings. This article aims to review current research and recommendations in order to provide guidance and practical advice for this environment. The article focuses on practices in England and Wales, which share the same mental health and criminal legislation. The principles addressed here can be applied to other jurisdictions, such as Ireland, the Isle of Man and Northern Ireland, where there are similar provisions derived from statute law, and to Scotland under common law.

Interviews and the criminal justice process

Mental health in-patient settings routinely provide multidisciplinary care for people experiencing or recovering from a mental disorder. During their care, the safety of patients, their visitors and staff is paramount. Consequently, any assaults or other alleged crimes are encouraged to be reported internally within the NHS trust and, where appropriate, to the police.

When a crime is reported to the police, they will attend to gather complainant and witness statements, collect hard evidence, such as anything used as a weapon, and collect supplementary evidence, such as CCTV recordings. Complainant and witness interviews are usually completed first, as they are often required to substantiate a crime. These are generally not ‘formal’ interviews and can be conducted at various places, including the place of the incident, a home address or a police station. When verified by an appropriate statement of truth, they become formally admissible in evidence without the necessity to give oral evidence unless it is challenged by the defence. In contrast, suspect interviews are considered formal from the outset because they are conducted following a caution (Box 1).

BOX 1 The police caution

‘You do not have to say anything. But it may harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned something which you later rely on in court. Anything that you do say may be given in evidence.’

(Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), Code C, para. 10.5: Home Office 2019)If consideration is given to conducting a formal interview in an in-patient setting, it is at this point that the police may request the treating team to assess whether the suspect is fit to be interviewed. In England and Wales, an individual can be convicted of a crime solely on confessional evidence (Gudjonnson Reference Gudjonsson1995, Reference Gudjonsson2003). Therefore, it is essential that the suspect's interview evidence, obtained from the police, is admissible. Of note, as witness and complainant interviews are not held under police caution, fitness to be interviewed assessments are not required (Peel Reference Peel2017). However, where a complainant or witness has a mental disorder, which is very likely in the case of offences committed in an in-patient setting, a psychiatric opinion may be sought regarding the likelihood of there being reasonable doubt as to the complainant's, or the witness's, competence as a witness or as to their reliability. In comparison to a suspect's fitness to be interviewed, the threshold for judging a witness to be competent is low. A witness can be judged competent if they can understand the questions put to them and give answers to questions which can be understood (Youth Justice and Criminal Evidence Act 1999, section 53(3)). As was held in R v Barker [2010]:

‘The statutory provisions […] apply to individuals of unsound mind. They apply to the infirm. The question in each case is whether the individual witness […] is competent to give evidence in the particular trial. The question is entirely witness […] specific. There are no presumptions or preconceptions. The witness need not understand the special importance that the truth should be told in court, and the witness need not understand every single question or give a readily understood answer to every question.’

The question of competence as a witness is decided on the balance of probabilities. The test as to reliability is different. It is whether there is something about the witness's mental condition that would give rise to reasonable doubt as to their reliability.

The assessor and the location of the assessment

Historically, in police custody, fitness to be interviewed was primarily assessed by forensic physicians (previously called forensic medical examiners) (Ventress Reference Ventress, Rix and Kent2008), who are registered medical practitioners with additional training in this field (Crouch Reference Crouch2005). In recent years, this function has largely shifted to other healthcare professionals, primarily custody nurses. As these assessments occur in police custody, the police custody officer remains responsible for the welfare of the suspect (Ventress Reference Ventress, Rix and Kent2008). On a psychiatric in-patient ward, it would be the treating team who assess fitness to be interviewed and they would maintain responsibility for the interviewee's well-being along with the clinician in charge of the individual's care; this is usually a consultant psychiatrist.

If the suspect is not deemed fit for interview, then the police are likely to follow the team's assessment and not complete the interview at this time. If the patient is deemed fit, the interview can potentially be completed on the ward. There are several advantages to this, including both logistical and safety benefits. The physical environment of a police station can cause stress to the extent of impairing the suspect's interview performance (Stark Reference Stark, Rix and Stark2020). Interviews on the ward may reduce some of this stress and minimise further disturbance, as the patient can remain in a more comfortable environment and continue engaging in therapeutic activities while awaiting interview. As the patient remains in a setting in which trained and familiar staff are able to attend to their mental health needs, there is likely to be improved patient care. If the incident occurred within the hospital, this can aid police efficiency as the police could potentially conduct all interviews on the same visit. This process can reduce the delay in the criminal justice process, which is particularly important for certain offences, such as common assault, which have to be prosecuted within 6 months. Interviewing in this setting can also potentially deliver the message that having a mental disorder is not necessarily a barrier to prosecution and that alleged criminal acts are taken seriously. However, there are some disadvantages to this approach. Some may feel that the ward environment should be therapeutic and that it would be inappropriate to interview in this setting. As it is not a common process, there may be some initial resistance to interviewing in this environment. Consequently, this approach is reliant on good links with the local police service, which may take time to build. Although there may be cost savings on secure transport, there would be an administrative cost associated with organising these interviews and a room fit for this purpose would be required.

After the interview

If the interview goes ahead, then once it is completed, standard charging procedures would apply and the police would seek advice from the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) as to whether the two-stage test was fulfilled: whether there is enough evidence to secure a conviction and whether it would be in the public interest to prosecute (Crown Prosecution Service 2017). The CPS will then give guidance on what offence, if any, the suspect should be charged with (Crown Prosecution Service 2017). Alternatively, out-of-court disposals such as, but not limited to, fines or cautions, are also available. These depend on the severity of the offence and the wishes of the victim. If the threshold to charge is met, then the case will probably be tried and the interview may be used in evidence. If the patient is not deemed fit to be interviewed, they can still be charged without interview if the two-stage test is satisfied (evidentiary threshold and public interest). The patient can be arrested at any point during this process if their risk is deemed to be too high to be managed safely within their current ward setting or due to the severity of the alleged offence. This whole process can take several months to complete (Ministry of Justice 2019) and thus a patient will often be discharged from the ward before their court date.

Defining fitness to be interviewed

Fitness to be interviewed is a two-part assessment. The first part relates to whether harm is likely to be caused to the individual and the second part relates to the individual's reliability. Code C of the Codes of Practice of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE) codifies good practice in relation to the detention, treatment and questioning of persons by police officers (Home Office 2019). It defines fitness as being ‘at risk’ in an interview (Box 2). Risk in this context appears to be related to vulnerability, which is described in Box 3.

BOX 2 Definition of fitness to be interviewed

‘A detainee may be at risk in an interview if it is considered that:

(a) conducting the interview could significantly harm the detainee's physical or mental state;

(b) anything the detainee says in the interview about their involvement or suspected involvement in the offence about which they are being interviewed might be considered unreliable in subsequent court proceedings because of their physical or mental state.’

BOX 3 Definition of ‘vulnerable’

‘“Vulnerable” applies to any person who, because of a mental health condition or mental disorder […]:

(i) may have difficulty understanding or communicating effectively about the full implications for them of any procedures and processes connected with:

• their arrest and detention; or (as the case may be)

• their voluntary attendance at a police station or their presence elsewhere […] for the purpose of a voluntary interview; and

• the exercise of their rights and entitlements

(ii) does not appear to understand the significance of what they are told, of questions they are asked or of their replies;

(iii) appears to be particularly prone to:

• becoming confused and unclear about their position;

• providing unreliable, misleading or incriminating information without knowing or wishing to do so;

• accepting or acting on suggestions from others without consciously knowing or wishing to do so; or

• readily agreeing to suggestions or proposals without any protest or question.’

(Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), Code C, para. 1.13(d): Home Office 2019)

Assessing fitness to be interviewed

In the mental health in-patient setting, assessing fitness to be interviewed often falls to the ward psychiatrist. This may be reasonable having regard to their skill set in that, at the completion of UK general adult psychiatry training, psychiatrists are expected to have expertise in assessing mental disorders, knowing mental health legislation and the broader legal framework and having experience in writing reports for external agencies (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2019). Training in other UK psychiatric subspecialties (e.g. forensic and child and adolescent psychiatry) also includes more specific curriculum items directly related to fitness to be interviewed (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2017, 2018).

At the start of the assessment, the clinician should obtain the interviewee's consent and reassess them for this purpose, even if the individual is already known to them. The interviewee should then be assessed against the criteria having regard to both ‘harm’ and ‘reliability’. If the interviewee is not able to give consent and does not have capacity to make this decision, then they should be managed in their best interest (Department for Constitutional Affairs 2007).

Harm

The interview process can include particularly probing questions and the way this might affect an interviewee needs to be considered (PACE Code C, annex G, para. 3(c)). In the case of R v Miller [1986], it was argued that the police interview caused the defendant, who was known to have a history of mental illness, ‘to suffer an episode of schizophrenic terror’, which produced a ‘state of involuntary insanity’. This could be seen as causing harm. Any police interview is likely to cause some degree of stress or anxiety and it is up to the person assessing fitness for interview to decide where ‘normal’ anxiety and stress becomes psychological harm. Code C provides guidelines for the police to help reduce the risk of harm. These include ensuring that regular breaks are offered while a suspect is being questioned (Code C, para. 12.8) and ensuring that oppressive techniques are not being used (Code C, para. 11.5). Such measures can also help reduce unreliability. Physical health conditions such as those causing significant pain, or those requiring emergency treatment, also need to be considered, especially if police interview would interrupt their management.

Reliability

Reliability can be more complex to establish and requires consideration of the individual's abilities in multiple areas (Box 4). These abilities are relevant to understanding the police caution; if the caution cannot be understood, even when simplified, then it is likely that the individual will be unfit to be interviewed.

BOX 4 Factors to consider when assessing reliability

Does the suspect's physical or mental state affect their ability to:

• understand the nature and purpose of the interview

• comprehend what is being asked

• appreciate the significance of any answers given

• make rational decisions about whether they want to say anything

(Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 (PACE), Code C, Annex G, 3(a): Home Office 2019)

When establishing fitness to be interviewed, assessing the interviewee's ability to understand the nature and purpose of the interview and what is being said is often easily established. However, the ability for the interviewee to appreciate the significance of the interview and make rational decisions is more complex and difficult to ascertain. It can be very difficult to know what ‘rational’ means in this situation and, given that a person without a mental disorder can appear irrational in this setting, this needs to be approached with caution. It requires a careful assessment of the individual's mental state, in addition to considering factors such as suggestibility, compliance and acquiescence, which can contribute to false confessions (Gudjonsson Reference Gudjonsson1990, Reference Gudjonsson, Hayes and Rowlands2000).

Suggestibility in this context is the extent to which the person accepts and acts on plausible suggestions or messages from others during formal interview in a closed social interaction (Gudjonnson Reference Gudjonsson2003). This can be hard to detect without formal psychological testing.

With regard to compliance, a patient may comply and give false information owing to, for example, fear or the desire to remove themselves from a situation that they are unable to tolerate (Rix Reference Rix1997). This could occur in individuals who are highly anxious (Gudjonsson Reference Gudjonsson, Hayes and Rowlands2000). Personality traits, especially those of a dependent nature, may lead individuals to be more submissive, agree to a confession made to protect another person (Ventress Reference Ventress, Rix and Kent2008) or give unreliable information. In R v Lawless [2009], the defendant, who was charged with murder, was prone to making up stories to gain attention. He had allegedly made admissions to others following the alleged murder but did not repeat this during police interview. The prosecution relied heavily on these admissions, as other evidence was limited. The defendant was initially found guilty but the conviction was quashed on appeal, after expert evidence found that the defendant had a ‘pathological dependency on other people's attention and therefore it was unsafe to rely on the defendant's alleged confessions’.

Acquiescence is the tendency of the individual to ‘answer questions affirmatively regardless of the content’ (Gudjonnson Reference Gudjonsson1990, p. 227). This tends more commonly to occur in those of ‘low intelligence’ (Gudjonnson Reference Gudjonsson1990). Other individuals may have traits to suggest that they are likely to exaggerate events without understanding the full implications of their disclosure (Ventress Reference Ventress, Rix and Kent2008).

Specific mental disorders carry a higher risk of leading to unreliable interview evidence (Rix Reference Rix1997; Ventress Reference Ventress, Rix and Kent2008). Ventress et al (Reference Ventress, Rix and Kent2008) and Kent & Gunasekaran (Reference Kent and Gunasekaran2010) have explored this in detail and a summary of these disorder-specific factors can be found in Table 1. Note that a diagnosis alone cannot determine fitness and thus healthcare professionals should ‘consider the functional ability of the detainee rather than simply relying on a medical diagnosis’ (Code C, Annex G, para. 4). For example, a psychotic illness does not necessarily render an individual unable to give their account of the incident in a reliable fashion, although it may be noted that their motive for the alleged offence may have been psychotically driven (Ventress Reference Ventress, Rix and Kent2008; Kent Reference Kent and Gunasekaran2010). It is important to highlight that, although reliability is related to truthfulness, it is the capacity for truthfulness rather than actual truthfulness that is important. Similarly, when we assess for reliability, we are assessing the potential for unreliability, as actual unreliability is a matter for the court to decide.

TABLE 1 Factors to consider in specific mental disorders when determining fitness to be interviewed

Most of the factors in Table 1 can be ascertained from a standard psychiatric history and mental state examination. Assessment of suggestibility, acquiescence and compliance may require formal psychological testing, which can be completed by a forensic psychologist.

Safeguards

In completing a fitness to be interviewed assessment, it is important to make appropriate recommendations. These can range from advice on how to interact with an individual to formal safeguards. Examples include advising the use of simple language with an individual with an intellectual disability or informing the police of an individual's specific delusional beliefs that could affect their interview.

The appropriate adult

The use of an ‘appropriate adult’ is a specific safeguard. Their role and the requirement for their deployment is set out in Code C, Annex E (Box 5). Code C, para. 3.5(c)ii has created a requirement for there to be an appropriate adult if the interviewee is ‘vulnerable’ (Box 3). Given that many of the patients on an in-patient mental health ward are likely to be considered vulnerable, we recommend that all patients having formal interviews are seen with an appropriate adult. If there are concerns during the interview process, then the appropriate adult should raise them with the appropriate person. In police custody this would be an officer of the rank of inspector or above, as specified in Code C. However, this would not be possible in an in-patient environment and we therefore propose that, if the concerns are noted specifically during the interview, then the appropriate adult can make them known to the solicitor and suggest that the interview is suspended. If there are concerns outside the interview, then this can be raised with the person within the hospital who is responsible for liaising with the police. In the UK this would be the hospital police liaison officer within the trust or the local security management specialist. Across the UK there are a number of schemes for training individuals to become appropriate adults. In a ward setting, it is possible that a registered mental health nurse or another multidisciplinary team member could fulfil this role.

BOX 5 Definition and role of the appropriate adult

‘In the case of a person who is vulnerable, the “appropriate adult” means:

(i) a relative, guardian or other person responsible for their care or custody;

(ii) someone experienced in dealing with vulnerable persons but who is not:

• a police officer

• employed by the police;

• under the direction or control of the chief officer of a police force;

• a person who provides services under contractual arrangements […] to assist that force in relation to the discharge of its chief officer's functions,

whether or not they are on duty at the time.

(iii) failing these, some other responsible adult aged 18 or over who is other than a person described in the bullet points in sub-paragraph (ii) above.’

The appropriate adult's role is:

‘to safeguard the rights, entitlements and welfare of “vulnerable persons” […] to whom the provisions of this and any other Code of Practice apply. For this reason, the appropriate adult is expected, amongst other things, to:

• support, advise and assist them when, in accordance with this Code or any other Code of Practice, they are given or asked to provide information or participate in any procedure;

• observe whether the police are acting properly and fairly to respect their rights and entitlements, and inform an officer of the rank of inspector or above if they consider that they are not;

• assist them to communicate with the police whilst respecting their right to say nothing unless they want to as set out in the terms of the caution;

• help them to understand their rights and ensure that those rights are protected and respected.’

Training for the appropriate adult role

Whenever new practices are being brought into a hospital, training, education and awareness are all needed for the wider multidisciplinary team that may be involved in the process. With regard to the appropriate adult, Code C does not mandate any specific training for this role but this would need to be discussed at a local level to determine who would be best placed to fulfil this duty and decide what additional training should be provided. Given that this role is not passive and can be demanding, we would recommend training to ensure that the multidisciplinary team member has the necessary knowledge of the criminal justice system and of Code C and can apply appropriate interventions so as to ensure the fairness and reliability of the interview. However, it is acknowledged that there is a balance to be struck between this and having an appropriate adult who has not completed any additional training but knows the patient well enough to support them and facilitate better communication. As a parent or an adult friend can be an appropriate adult, this can be considered, especially if it would help the interviewer to conduct a better interview by putting the interviewee at ease.

The solicitor

All suspects undergoing formal police interview should be offered a solicitor to represent them and provide legal advice. Police stations have a duty solicitor 24 h a day who would be able to attend if the interviewee had not appointed their own. The police have a duty to inform the suspect of this right and an appropriate adult can further help in ensuring that the interviewee understands the benefit of a solicitor. We would recommend that all patients are interviewed with a solicitor.

Outcome of assessment

In custody, the role of the healthcare professional is ‘to consider the risks and advise the custody officer of the outcome of that consideration’ (Code C, Annex G, para. 7). It is then the custody officer who decides ‘whether or not to allow the interview to go ahead’ and ‘determine[s] what safeguards are needed’ (Code C, Annex G, para. 8). On the ward, this onus would lie with the clinical staff. Potential outcomes from fitness to be interviewed assessments are not specified in Code C but these have been helpfully suggested by a Home Office Working Group (Home Office 2001), which looked at different levels of ‘risk’ (Table 2).

TABLE 2 Outcomes for fitness to be interviewed assessments, with examples

Source: Home Office (2001).

If the individual is deemed unfit, being at definite or major risk, then the clinician should document whether this is likely to change with further management, whether reassessment would be appropriate and when this should occur. If they are deemed fit, it is important to note that, if there has been significant change in their health after the initial assessment but prior to the police interview, then fitness should be reassessed. Additional general recommendations can be given at any point.

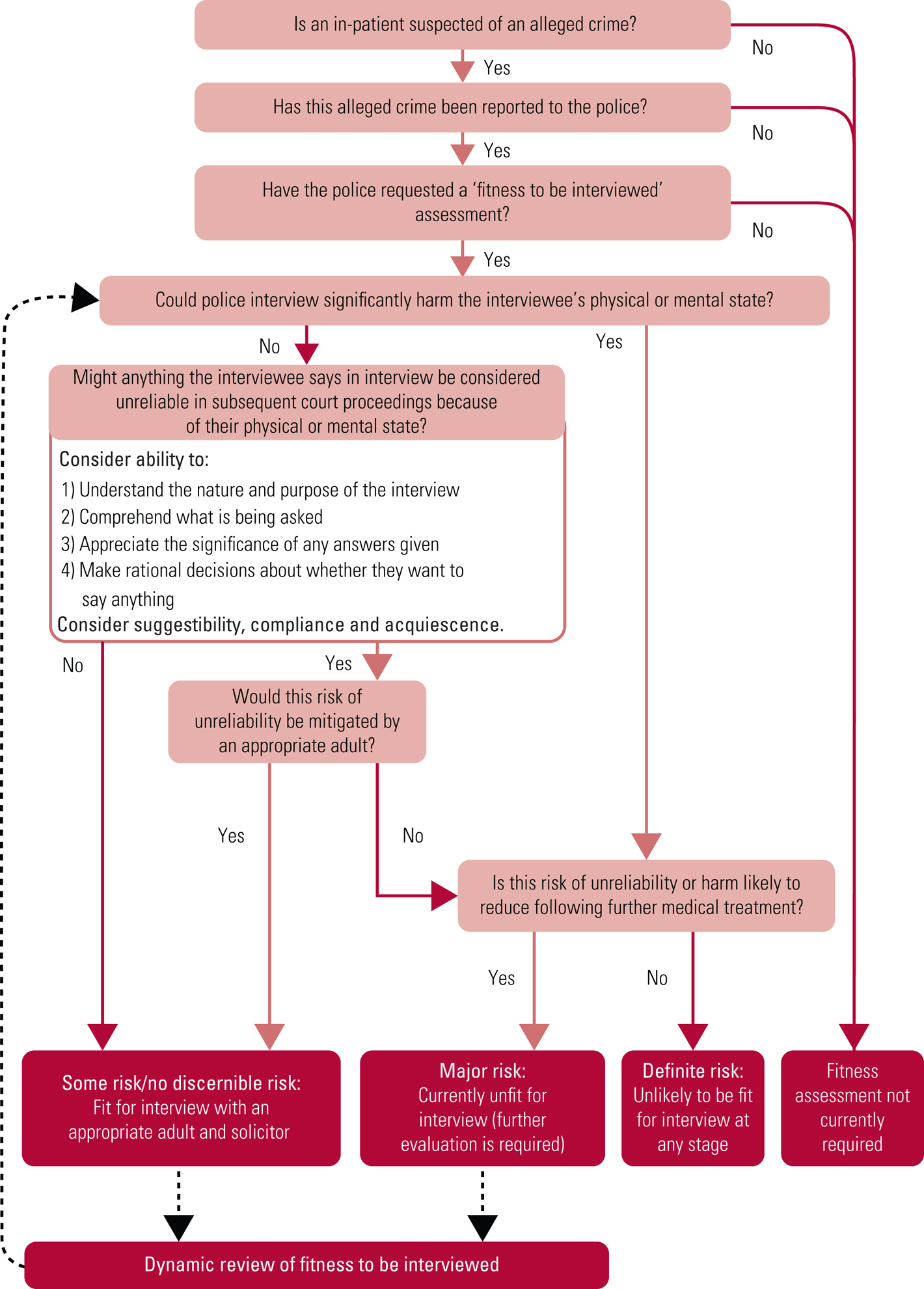

This whole process is summarised in Fig. 1.

FIG 1 Summary of assessing fitness to be interviewed in the in-patient setting.

Capacity versus fitness

Fitness to be interviewed assessments are commonly likened to mental capacity assessments (Kent Reference Kent and Gunasekaran2010). There are indeed some similarities but is it important for clinicians to know the differences. According to the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) a ‘person lacks capacity in relation to a matter if at the material time he is unable to make a decision for himself in relation to the matter because of an impairment of, or a disturbance in the functioning of, the mind or brain’ (MCA, s. 2(1)). Fitness assessments are distinct in that other physical health concerns are considered, not only those causing an impairment of the mind or brain. The MCA further states that a ‘person is unable to make a decision for himself if he is unable (a) to understand the information relevant to the decision, (b) to retain that information, (c) to use or weigh that information as part of the process of making the decision, or (d) to communicate his decision’ (MCA, s. 3(1)); it is this part that bears most resemblance to the fitness to be interviewed assessment. The similarities and differences are summarised in Table 3.

TABLE 3 Comparison between fitness to be interviewed and mental capacity assessments

Practical issues

With all new interventions, it is essential to think about clinical governance, quality assurance, the environment and patient safety. It is important to consider who would be the most appropriate person to complete the fitness assessment. Although the psychiatrist involved in the patient's care is likely to know the patient and could be in a better position to assess the patient more accurately, the potential risk of bias needs to be considered, particularly if the assessor knows or works with the complainant. Bias could present as not wishing an individual to be prosecuted and thus assessing the suspect as not being fit for interview or vice versa. Teams should be careful to avoid this.

Documenting the assessment

After the assessment has been completed, it should be documented. In police custody, fitness to be interviewed assessments are required to be written within the custody records. As clinical staff would not have access to this document, the fitness assessment could be documented on a witness statement form and a copy could be included in the patient's medical records. A template that could be used for this statement is included in the supplementary material, available at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2020.49. As information is being provided to the police, an external body, information governance and confidentiality need to be considered. In explaining and documenting a patient's fitness assessment, information about their medical history and mental state examination may need to be shared. The General Medical Council (2018) informs that doctors should ask for consent from patients before disclosing confidential information. If they do not have the capacity to consent, then disclosures can be made ‘if it is of overall benefit to the patient’ (General Medical Council 2018, para. 16).

The interview room

Once the interview date has been set, the interviewee should be made aware of the interview process, which may help to reduce any anxiety. A suitable room should then be booked. PACE Code C (para. 12.4) lists fairly basic requirements for an interview space, stating that the room needs to be adequately heated, ventilated and lit. As an authorised audio recording device (usually a portable tape recorder) would be required, the room would need to be quiet, confidential and have sufficient space to accommodate a table and all necessary persons (minimum of four). Panic alarms would provide additional safety and, ideally, a space off the ward within the hospital grounds would be preferable. This can help to maintain their confidentiality and separate the therapeutic environment of the ward from the place of criminal investigation. However, in some settings (such as secure facilities), this may not be practically possible and thus the interview would have to be completed on the ward.

Prosecution in the public interest

Following interview, the CPS may decide not to prosecute patients already admitted to a mental health unit, owing to concerns that it would not be in the public interest. However, Wilson et al (Reference Wilson, Murray and Harris2012) argue that there are potential benefits in reporting ‘non-trivial assaults’ to the police and they describe factors that can be considered as indicating a public interest to prosecute. These include discouraging violent behaviour, creating safer services, managing risk following hospital discharge (or transfer) and shared learning with different mental health teams to improve their care. Therefore, regardless of any perceived reluctance on the part of the police to investigate, there is an argument for reporting these alleged offences to the police and ensuring that, following the appropriate police investigation, the CPS has all of the necessary information for deciding whether it is in the public interest to prosecute.

Fictional case vignettes

Lucy

Lucy is a 55-year-old woman with a 3-month history of low mood. She was admitted following an overdose of 28 antidepressant tablets with the intent to end her life. On admission she reported anergia, anhedonia, early morning awakening and had lost weight as she believed that her bowels were shrinking and therefore she could not eat. She ruminated on negative thoughts, continually blamed herself for others’ difficulties and subsequently believed that she should be punished. While on the ward, her medication was changed. Her sleep, appetite and mood started to improve but she continued experiencing guilty and suicidal thoughts. While on the ward she was accused of assaulting another patient. The police asked whether she was fit to be interviewed.

Owing to Lucy's morbid guilty thoughts, there is a risk that she will give false incriminating evidence as a way to punish herself. This would increase her risk of unreliability and she would therefore be considered unfit to be interviewed. However, given that she is now responding to treatment, her fitness could be reassessed within an appropriate time frame, by which point there may be a further improvement in her symptoms and negative thoughts.

Mario

Mario is a 29-year-old man with an established diagnosis of schizophrenia. He was admitted with a relapse following non-concordance with his medication. He reported auditory hallucinations and expressed delusional beliefs that his neighbours were pumping toxic gas through his letter box and poisoning his food. While on the ward, he felt safe and engaged well in his treatment. His hallucinations and delusional beliefs were less intense though still present. One afternoon, Mario saw another patient wearing his shoes and he allegedly punched him several times, causing a significant injury. This was reported to the police, who asked whether Mario was fit to be interviewed.

Even though Mario is currently psychotic with active delusional beliefs, these are in the context of his neighbours at home and are not related to the alleged offence. In this situation he may still be able to provide reliable information about the incident, but it would be beneficial for the police to be aware of these delusional beliefs and for him to be seen with both an appropriate adult and a solicitor.

Conclusions

When a patient is suspected of being involved in an alleged crime in an in-patient psychiatric setting, psychiatrists have a clear role in conducting fitness to be interviewed assessments that are requested by the police. This article offers a summary of this decision-making process within this setting and highlights practical considerations. Ensuring that safeguards are available for all patient interviewees and that appropriately trained and experienced staff are aware of their ongoing responsibilities are key to ensuring a fair process and a just outcome for both the suspect and the complainant, ultimately helping to prevent a miscarriage of justice.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2020.49.

Author contributions

A.E.: substantial contributions to the conception, initial and final drafting of the paper. S.J.: substantial contributions to the reviewing and redrafting of the paper, particularly with regard to the criminal justice system and policing perspective. K.J.B.R.: substantial contributions to the reviewing and redrafting of the paper, particularly with regard to the legal aspect. F.S.: substantial contributions to the conception and reviewing of the paper, particularly with regard to the practicalities of using this assessment within an in-patient setting.

Declaration of interest

None.

ICMJE forms are in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2020.49.

MCQs

Miss Smith is a 37-year-old with a known history of schizoaffective disorder. She was admitted to a psychiatric ward following a manic relapse. She has allegedly assaulted another patient on the ward and the police have asked you to assess her fitness to be interviewed.

Select the single best option for each question stem:

1 When assessing Miss Smith's fitness to be interviewed, you do not need to consider:

a whether conducting the interview could significantly harm Miss Smith's physical or mental state

b whether she can appoint an appropriate adult

c whether she can comprehend what is being asked and appreciate the significance of her responses to questions

d whether she can make rational decisions about whether she wants to answer certain questions

e whether she can understand the nature and purpose of the interview.

2 The police want to interview another female patient who witnessed the incident. You need to consider:

a whether she can understand the special importance that the truth should be told in court

b whether she can understand the questions put to her and give answers to questions that can be understood

c whether she can understand every question put to her

d whether she can give a readily understandable answer to every question

e whether she is fit to be interviewed.

3 You feel that Miss Smith would benefit from having an appropriate adult in the interview. Of the following, the most appropriate person to fulfil this role would be:

a a clinical staff member who has received training on being an appropriate adult

b Miss Smith's mature 15-year-old daughter, who will be visiting her on the day of the interview

c one of the police officers attending who has extensive knowledge of the role of an appropriate adult and Code C of PACE

d the nurse in charge of the ward

e the psychiatric ward registrar.

4 When arranging a room for the interview, the basic requirements informed by Code C of PACE are that:

a it should be adequately lit, have a panic button and be quiet/confidential

b it should be well lit, ventilated and adequately heated

c it should have soft furnishings, be well lit and warm

d it should have reasonable lighting, ventilation and a panic button

e it should have good ventilation and heating; it should not have a window as this could breach confidentiality.

5 On the morning of the interview, Miss Smith absconded and used illicit drugs which exacerbated her symptoms and she is now acutely manic. You are not sure that she would now appreciate the significance of the interview and her responses to questions even with the presence of an appropriate adult. You should:

a cancel the interview, as she has a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder and thus would never have been fit for interview

b continue with the interview, as the fitness assessment has already been completed and indicates that she is fit to be interviewed

c continue with the interview, but make the solicitor and appropriate adult aware of the recent events

d go ahead with the interview, but ensure that there are both an appropriate adult and a staff member who knows her well in the interview

e reassess her fitness to be interviewed and cancel the interview if she is not fit.

MCQ answers

1 b 2 b 3 a 4 b 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.