Introduction

‘The voices had me believing that I wouldn’t be waking up in the morning. And um they said they were going to skin me um, rape me, all this horrible stuff ’ [voice hearer, V13]

Since the seminal paper by Chadwick and Birchwood (Reference Chadwick and Birchwood1994) over 25 years ago, substantial literature has amassed demonstrating that how voice hearers appraise voices affects both the degree of distress and the response (Birchwood and Chadwick, Reference Birchwood and Chadwick1997; Chadwick and Birchwood, Reference Chadwick and Birchwood1995; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Williams, Cooke and Kuipers2012; Varese et al., Reference Varese, Morrison, Beck, Heffernan, Law and Bentall2016). Targeting these appraisals using cognitive behavioural therapy leads to clinical benefits on hallucinations (Turner et al., Reference Turner, Burger, Smit, Valmaggia and van der Gaag2020). Building on this literature, and the development of targeted treatments for voice hearing (Birchwood et al., Reference Birchwood, Michail, Meaden, Tarrier, Lewis, Wykes and Peters2014; Birchwood et al., Reference Birchwood, Dunn, Meaden, Tarrier, Lewis, Wykes and Peters2018), we aimed to improve the cognitive understanding of one particular presentation of voices that has not been systematically investigated: derogatory and threatening voices (DTVs).

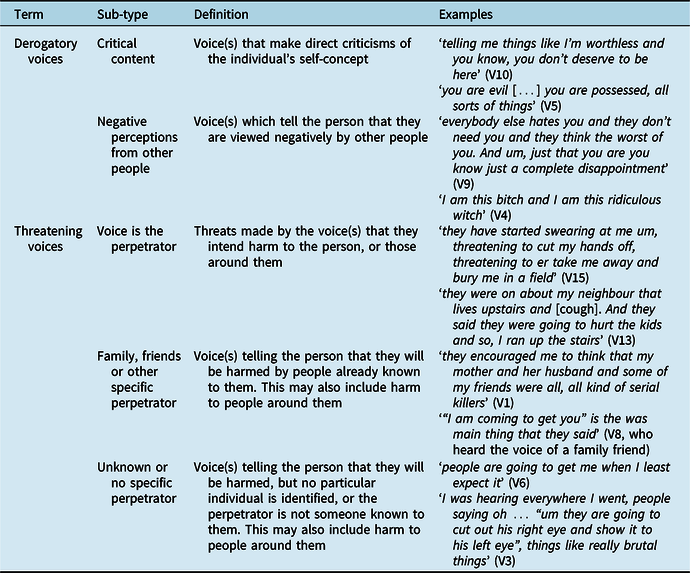

Around two-thirds of voices are derogatory or threatening to the patient (McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Trauer, Mackinnon, Sims, Thomas and Copolov2014; Nayani and David, Reference Nayani and David1996; see Table 1 for definition and examples). Voice hearers most often describe these voices as seeming very real (McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Trauer, Mackinnon, Sims, Thomas and Copolov2014), believable, and difficult to ignore. It is therefore understandable that depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation are common consequences. This paper seeks to identify appraisals which result in listening to and believing derogatory and threatening voice content. A crucial first step in this process is to listen and learn from the people who have this voice experience.

Table 1. Definitions of derogatory and threatening voices (DTVs) with illustrative examples

Note that participants may endorse more than one sub-type of DTV.

Method

Participants

A pilot stage, early in sampling, ensured specific diversity based on the following characteristics: age, duration of hearing voices and employment status. In-patient or out-patient status was also a characteristic; however, it proved difficult to identify in-patients who felt able to talk about their voice hearing. Subsequently, theoretical sampling was used to recruit participants who hear DTVs. Interviews were analysed concurrently with recruitment such that subsequent sampling was driven by the emerging theory and testing of it. A maximum of 20 participants was sought, but theoretical saturation (Corbin and Strauss, Reference Corbin and Strauss2015) was felt to have been reached by 15 participants and hence recruitment ceased. Theoretical saturation was defined as no new reasons for listening to or believing voices emerging from the data, and that each reason was sufficiently saturated and elaborated.

Participants were recruited from Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. Clinical teams referred patients to author B.S. who completed a telephone screening with the referrer and the potential participant. Inclusion criteria were: daily experience (either current or past) of DTVs; experience of DTVs for at least 3 months; a willingness and ability to recall and discuss their experience in detail; fluent in English; age 18–65 years; willingness and ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were: moderate to severe learning disability; voices caused by an organic syndrome (e.g. dementia, significant head injury) and voices occurring solely within the context of substance misuse, personality disorder or a mood episode (depression or mania). See Supplementary material section A for further detail on methods.

Procedure

The study was approved by an NHS research ethics committee (reference no. 18/SC/0443). An audio-recorded semi-structured interview was conducted using a topic guide by B.S. The interview intended to generate the participants’ own detailed description of their experience rather than merely responding to closed questions. The audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim by an external transcription company. For the interview process and topic guide, see Supplementary material section B. L.G. (a qualitative methodologist) consulted on the protocol, topic guide, emerging categories from an early interview and the subsequent coding framework.

Analysis

A grounded theory methodology (Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967) was used as it is intended to generate a theory about a complex process about which little is already known. NVivo 12 (QSR International Pty Ltd, 2018) facilitated coding. Free coding was used with the first three transcripts in order to generate an initial coding framework. The framework focused on psychological variables (beliefs, emotion and behavioural responses) alongside other pertinent descriptions of experience derived from the data (e.g. isolation, suicidal thoughts). A research diary was completed logging decisions in the theory generation, theoretical sampling and analysis. This ensured transparency in the iterative process. A second clinical psychologist who specialises in psychosis research acted as a second rater for one interview, using the framework generated by B.S. in order to enhance credibility of ratings. The coding framework and illustrative quotes were presented to a lived experience advisory panel (LEAP) who relabelled some of the codes and confirmed the appropriateness of the overall framework. This framework was subsequently applied to later interviews using the constant comparison method. New codes were added as they emerged, and all interviews were subsequently re-coded to enhance dependability. Finally, the results were discussed with the LEAP who confirmed the overall structure of the results, and either confirmed the appropriateness of each code, or adjusted the name after discussion with B.S.

Results

Fifteen participants were recruited. Table 1 shows analysis of the sub-types of DTV content that is listened to and believed. Table 2 provides demographic and clinical characteristics.

Table 2. Demographics and clinical characteristics (n = 15)

The impact of derogatory and threatening voices

Participants described severe anxiety (e.g. ‘it’s a scary, scary, scary, scary situation, I’ve had more fear in the last two years [pause] than anywhere in my life’, V15), depression (e.g. ‘when the torture starts […] I will feel so depressed I’m just in bed’, V4) and anger (e.g. ‘I haven’t had any kind of aggressive outbursts in terms of towards anybody else in the real world, but I’ve most definitely been aggressive towards the things in my mind’, V1). Isolation was a prominent theme (e.g. ‘it’s a pretty lonely place’, V15). Every participant described self-harm, suicidal ideation or attempts, despite not being directly asked about it (e.g. ‘the only thing I would do or felt I was able to do when I heard voices was to hurt myself and that’s the only way I could get it to stop’, V10).

Reasons for listening to and believing derogatory and threatening voices

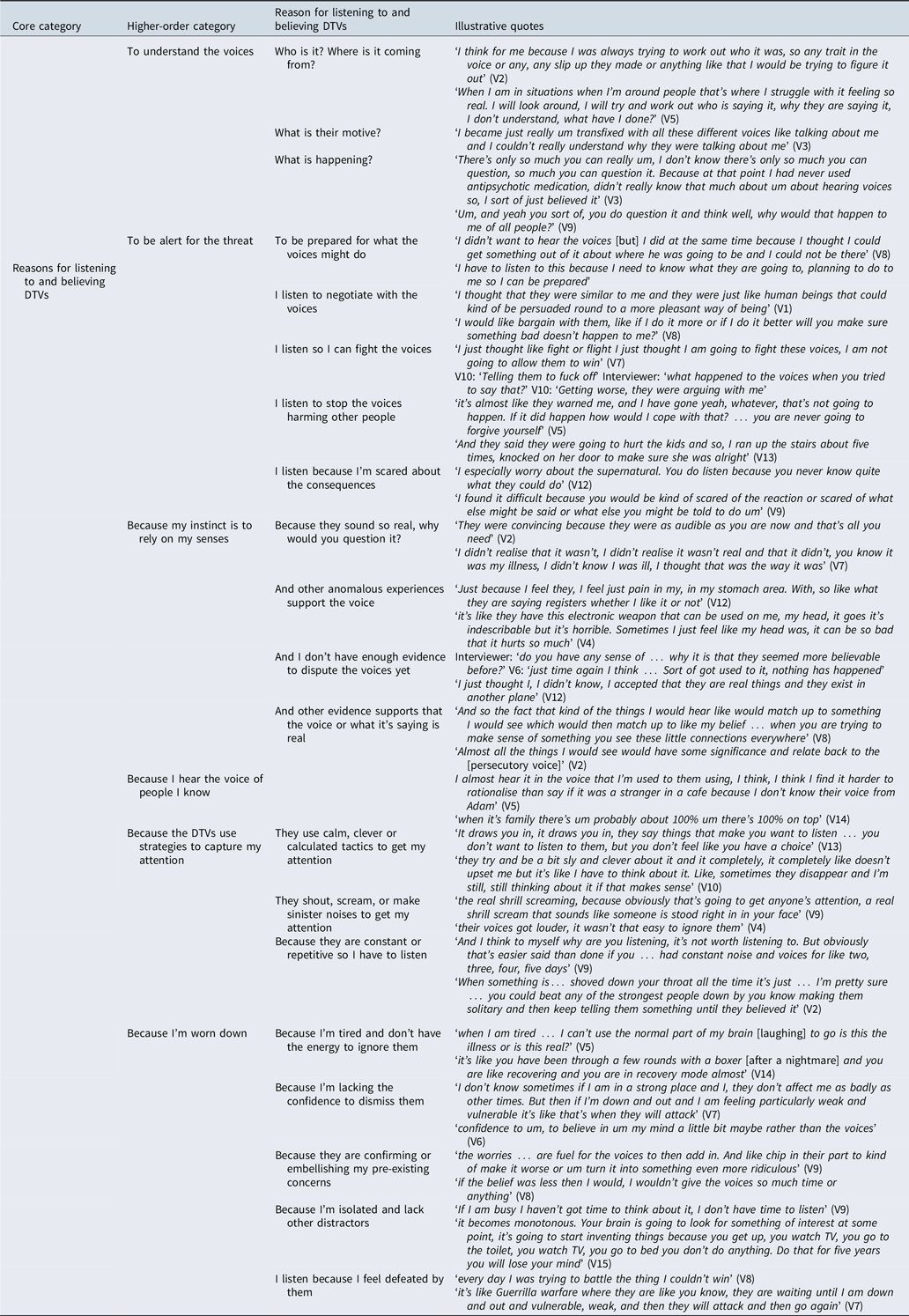

Six higher-order categories were derived. Within these higher-order categories were 21 reasons for listening to and believing DTVs (see Table 3). Each participant endorsed between three and nine reasons.

Table 3. Category structure of reasons for listening to and believing DTVs

Desire to understand the voices

V2: ‘If it killed me it didn’t matter, I just wanted to know what was happening’.

Participants described a range of questions (who, why, what, how and where) which served as reasons for listening to distressing content.

Who is it? Where is it coming from?

Several participants described keeping DTVs in their attention to work out who the voice was, for example ‘when I’m around people that’s where I struggle with it feeling so real. I will look around, I will try and work out who is saying it, why they are saying it, I don’t understand, what have I done?’ (V5). For V12, identifying the culprit was important to assess their ability to harm: ‘Because I don’t know who they are, what they represent, what they could do to me’. Identifying the location of voices served as another reason for focusing on them: ‘I just don’t understand where it’s coming from. It’s frustrating’ (V15). V2 explained that if he can see where the sound is coming from it is easier to ignore: ‘that’s the difference you know if you sit here calling me a paedophile and a cunt and everything…. No, that’s not just the difference, the difference is that I can see you saying it’.

What is their motive?

Many participants described wanting to identify the intention of the voice or work out why particular threats or derogatory remarks were made. For V13 this was associated with arguing with the voices: ‘I just don’t understand why they are doing it. I just can’t understand, some of the things they say, I argue with them every night’.

What is happening?

Several participants were trying to understand why they were experiencing DTVs and did not have an adequate explanation, for example ‘… didn’t really know that much about um about hearing voices so, I sort of just believed it’ (V3). V6 read a psychology textbook to learn about his condition and explained ‘it helped me not to believe in them so much’. V5 described how a friend shared a rationale for the DTVs which helped her question them on a bad day: ‘I reckon she was on and off the end of the phone for a good couple of hours before I realised okay, maybe she is right, I’m really tired, I’m really low, I’m really agitated. This is probably because of the muck up with my meds… So, when she talked me down I started to be able to rationalise things’. Explanations for DTVs that had been shared with participants by professionals were not always sufficient. V15 described: ‘I mean why would my brain tell me that I’m a paedophile when I’m not?’, and V3 explained that his diagnosis was helpful for questioning the DTVs, but only after some time: ‘I had been told by that psychologist that I had psychosis and even if I didn’t believe her I still had that in my head so’.

To be alert for the threat

To be prepared for what the voices might do

A few participants noted listening to threatening voices in order to be prepared for voices’ threat, e.g. ‘I’ve got to listen to this because I need to know what they are […] planning to do to me so I can be prepared’ (V15). This led to precautionary strategies and escape plans, for example ‘I make sure there’s no weapons lying around that they can get at, but I certainly know where things are that I can pick up’ (V15) and ‘my life was in jeopardy, so I acted on trying to find a safer place’ (V1).

To negotiate with the voices

Several participants described listening in order to reason with DTVs. This was pertinent for V1 who had tried persuasion ‘kind of persuade them to be nicer’ and doing things to change the voices ‘from […] playing music to kind of preaching about […] the awesomeness of existence’. V5 tried using logic: ‘I would be like “that’s ridiculous that’s not even logical, like I know they are not in [London] … So, how do you propose that you are going to do that there?”’. V8 tried to please the voices ‘I would like bargain with them, like if I do it more or if I do it better will you make sure something bad doesn’t happen to me?’ but did not negotiate with the most threatening voice ‘the main [voice] I don’t think I ever bargained, I think I was so scared that I would just sit and, I don’t think there was any point in bargaining’. Several participants noted reasons for not attempting to negotiate with DTVs (see Supplementary material section C).

Because I’m fighting them

The majority of participants described confronting the DTVs. They did not explicitly state that they listened in order to engage in a fight, but this is implied in the descriptions, for example: ‘I was just taking them on, I was like I’m not having this anymore … you are not going to rule over me all the time’ (V7). For some, a physical confrontation ‘okay, let’s go outside’ (V15), a mental argument ‘I’ve definitely been aggressive to the things in my mind’ (V1) or more passive strategies ‘I don’t need to fight back … I can just annoy them with cigarettes and alcohol’ (V12) were described. Reasons for fighting with voices are outlined in Supplementary material section C.

Because it’s my responsibility to stop them harming others

A few participants described feeling responsible for stopping DTVs harming others and this provided a rationale for engaging with them, for example ‘it’s almost like they warned me, and I have gone yeah, whatever, that’s not going to happen. If it did happen how would I cope with that? … you are never going to forgive yourself’ (V5).

Because I’m scared about the consequences

Several participants noted being scared of the consequences of not listening to the voices, or doing what they say ‘Oh, they will screw me more’ (V4). For some, there was a fear of voices getting worse: ‘I found it difficult because you would be […] scared of the reaction or scared of what else might be said’ (V9), or there being negative consequences after death (see Table 3, V12). One participant who did not listen to or believe his voices noted ‘[If] I dismiss something negative I’m not concerned that something negative will come out’ (V11) and two participants noted learning over time how to manage this fear: ‘if I tolerate it and try and keep going there’s less kind of retaliation from the noise and from the voices there’ (V9).

Because my instinct is to rely on my senses

Because they sound so real, why would you question it?

Several participants described initially accepting that the voices were real: ‘I didn’t realise it wasn’t real and that … it was my illness, I didn’t know I was ill, I thought that was the way it was’ (V7). V3 explained away why others were not hearing what he heard: ‘I thought that I had like superior hearing to other people […] because I was hearing these things that other people weren’t’.

Other anomalous experiences support the voice

A few participants reported tactile hallucinations linked to their voice hearing. V4 described this as ‘torture’ explaining: ‘they have this electronic weapon that can be used on me, my head… it’s indescribable but it’s horrible’. This directly linked to her listening to the DTVs: ‘you try to ignore him and that, that’s not acceptable to him. And he beats you up to force you to hear’. Some participants described visual hallucinations at the time of hearing voices: V5: ‘they were telling me that like a woman was coming with a gun, […] she would find a way to shoot me … I laid on my bed like battling about it and then I looked up and like in the doorway … she was just stood there’. A few participants described olfactory hallucinations which kept the DTVs in attentional focus. V5 described this as an early indicator of relapse: ‘I know I’m getting ill because one of the first things is everything starts smelling chemical … like as I’m smelling things they will be telling me that people are going to poison me’.

V8 experienced nightmares depicting the threats made by her DTV. Dreaming about being captured by the DTV made the voice’s threats more compelling: ‘Like, the dreams felt very real’. Several participants noted that acute fear from nightmares exacerbated voices. For V1 it triggered an acute episode of DTVs: ‘… the second time it was basically coming from the back of a very nasty experience in a dream’. V14 explained that he is less active the day after experiencing nightmares which means there are fewer distractions from the DTVs: ‘it’s like you have been through a few rounds with a boxer and you are like recovering and you are in recovery mode almost’.

Because I don’t have enough evidence to dispute the voices

Several participants who had experienced DTVs for several years noted initially believing them: ‘Well, it’s been so long and the thing that I’ve been thinking you know … none of the things that I was thinking about have actually occurred…’ (V1). For V6 both habituation (‘I got used to it’) and evidence gathering (‘nothing has happened’) enabled him to believe them less. Evidence was helpful for resisting demands: ‘since I was what 13, 14 so sort of 20 years, they have told me things are going to happen and they never have … Whether I’ve done it or not the things have never happened’ (V5) and improving mood: ‘it’s been a couple of years now … nothing particularly bad has happened and I can [pause] find a lot more peace … So, I’m quite, happier really, but they are still there’ (V12). Not all participants, however, noted a change over time: ‘I don’t think it has, just the same’ (V11).

Because other evidence supports that the voice and/or what it’s saying is real

Many participants described evidence which supported the veracity of what the DTVs said, or that they are real entities. V1 found the voice content difficult to comprehend but considered ‘the second world war. And you think well, those people were totally evil, they would be thinking the same kind of things in terms of murdering anything they didn’t like’. He also felt victimised whilst playing a computer game and thought ‘Maybe you are a victim in some kind of way … so that was kind of reinforcing the kind of thinking that it’s all a reality in terms of having real people in my mind’. V5 described concrete evidence that people she knew were DTVs: ‘if you were to say something at the same time and I saw your mouth moving as they said it I might think it was you. And it’s happened, like with my mum it happens quite a lot’. Some participants described a confirmatory bias: ‘Almost all the things I would see would have some significance and relate back to the [DTV]’ (V8).

Because I hear the voice of someone I know

A number of participants described hearing the voice of family members, friends, ex-friends, famous people and other people they had met momentarily which made DTVs more difficult to question or ignore. For some, the voice content was congruent with what was known about the person ‘they are doing exactly what they did when I fell out with them’ (V13) and for others it was incongruent ‘technically you would think I should go “well, I know them, they wouldn’t say that”’ (V5). Four participants commented that hearing a voice of someone familiar was more difficult: ‘when it’s family there’s um probably about 100% um there’s 100% on top’ (V14).

There were a range of reasons why these were more difficult to ignore, including: ‘it’s one of the voices that you trust more than anything’ (V14), because the voice content could reflect an already difficult relationship ‘with in laws… you don’t know what they think about you’ (V2), because of prior experience of the person’s intentions ‘I think they are just trying to finish the job’ (V13), because the person is used to listening to that voice ‘I hear them in the voice that I’m used to them using’ (V5), because hearing a famous person can lead you to ‘get immersed in it like you are almost famous’ (V14), and simply because they exist ‘this guy must be real, it must be the guy that I saw two months ago … because it’s his voice I’ve been hearing’ (V3). One participant conversely found that if he heard voices of people he recognised they were easier to dismiss than other voices ‘the ones that are people I know they are the ones I can, I can sort of rationalise if you like: “well this is ridiculous…there’s no way I can hear your thoughts”’ (V7).

Because the DTVs use communication strategies that capture attention

Because the voices use calm, clever or calculated tactics

Participants described a range of ways that the DTVs are ‘calm and calculated in what they say’ (V10) and that this captured attention. This was central for V10 who described that DTVs were captivating because: (1) they were quieter and easier to listen to than angry ones because ‘it’s not as scary I suppose’ and (2) they intentionally say things to provoke intrigue ‘because sometimes I don’t understand it like and it makes me think about what they are saying … maybe that’s why they are doing it’. Four other participants described finding that when voices are quiet or whisper, this encourages listening, for example: ‘the quieter they get the more … I find myself trying to really listen to it’ (V5). However, V5’s reason for listening was different from V10’s: ‘I guess the louder they are the more clearly, I know what’s being said … and can rationalise what’s being said’. For V13 this whispering was an intentional tactic: ‘because the sound, it makes you want to listen, the voices, the voices do it as well and it just makes you want to listen to them’. DTVs provoking intrigue was also described by others. They triggered forgotten memories ‘the memories like, when they say things from the past and that, things you had forgotten like and you remember it. Sort of grabs your attention’ (V13), had unexpected knowledge ‘it’s things… you just think people shouldn’t know about you’ (V3), and asked questions ‘they’re going “oh, hasn’t he worked it out yet?”… so I’m thinking, what haven’t I worked out?’ (V15). For one person it was the intelligence of the DTV: ‘you hear something intelligent back you tend to be more alert, your ears prick up a bit’ (V14).

Because the voices shout, scream or make sinister noises

Several participants noted ‘the voices got louder, it wasn’t that easy to ignore them’ (V4). For others it was their manner as well as volume: ‘a real sick, sick kind of manner’ (V1). For V9 a noise served as a means of the DTV capturing attention: ‘when the voices have got your attention that’s when the conversation can kind of start … like the derogatory and the violent comments’. She noted that some noises she has habituated to over time ‘it’s not as effective as it used to be, it’s been going on for so long’, but this hasn’t happened with other noises ‘I get like a sinister laugh which I still get like even to this day. That’s probably the only thing now that would get my attention more because it’s quite unnerving’ and because this noise is uncomfortable: ‘I’m almost listening for it’.

Because they are constant or repetitive

Several participants noted listening to or believing voices because they are constant, or repeat what they say, e.g. ‘And I think to myself why are you listening, it’s not worth listening to. But obviously that’s easier said than done if you […] had constant noise and voices for like two, three, four, five days’ (V9).

Because I’m worn down

Because I’m tired and don’t have the energy to ignore them

All participants reported disturbed sleep or energy levels. Many participants reported sleep disruption leading to voices being more difficult to ignore. One participant explained ‘Yeah, it’s not so much the voices are any different to any other day it’s my ability to rationalise them’ (V5), whereas another said that they have less control ‘when I haven’t slept that’s, that’s when I struggle to, to even like er, I struggle to like even make them stop’ (V10) and V13 described that sleep disruption led to the DTVs becoming louder: ‘They would be a lot louder and I would hear them more’.

Because I’m lacking self confidence

Almost all participants described difficulties with self-confidence. A few noted that their own lack of physical strength meant that an attack from the voices would be more likely to succeed: ‘I don’t have the strength or physical ability to defend myself […] and it is kind of compounded the fear factor’ (V1). Others noted that voices intentionally targeted them when they were vulnerable (V7, Table 3) and the content embellishes pre-existing concerns: ‘I’m feeling stupid or I’m feeling overweight or whatever and […] that’s what I will hear’ (V7). For others, confidence was required in order to test whether the DTVs were real; for example, V6 was asked what prompted him to ask friends ‘did you just say that?’ and explained ‘Maybe I sort of got a bit more self-confident’. He also noted that this questioning relies on the ‘confidence … to believe in um my mind a little bit maybe rather than the voices’. For V14, a low opinion of his intelligence impacted on his perception that he could rationalise the voices ‘not intelligent enough to’ and his desire to seek psychological therapy ‘if I ever started talking it wouldn’t be anything constructive, or anything good, or anything valuable coming out of my mouth’.

Because the voices are confirming or embellishing pre-existing concerns

Several participants described DTVs confirming, exaggerating or embellishing pre-existing concerns. V9 explained ‘I would panic people would get in the house. And then obviously the voices would kick in and say someone is going to be in the house, someone is going to take this, people are going to do this…’. For some participants their primary problem appeared to be paranoia (V8: ‘if the belief was less then […], I wouldn’t give the voices so much time’). For others their low mood and associated negative thoughts made them more inclined to believe derogatory remarks: ‘I mean I suffer from depression … you have always got that thing in the back of your mind that you are […] no good, a no-good character’ (V14).

Because of isolation and lack of mental stimulation

Inactivity and lack of stimulation was common, e.g. ‘not going outside at all for a month’ (V3) and provided time to listen to the voices: ‘If I’m busy I haven’t got time to think about it, I don’t have time to listen’ (V9). Night-time was problematic because of the quiet and lack of distraction: ‘it’s so quiet and everything is still and you listen because you hear more. And it’s almost like sometimes you lay there waiting to hear it’ (V9). For some participants, being busy was also an opportunity to gain new information: ‘it gives you another out, another perspective on a day rather than spending it cooped up in your flat thinking’ (V14).

Because I give up, I’m defeated by them

Participants frequently described managing the voices as an ongoing battle: ‘every day I was trying to battle the thing I couldn’t win’ (V8). Given the persistent nature of the voices, however, nine participants described listening because they felt defeated by them. For some, this directly led to times of vulnerability for attacks from the voices: ‘it’s like Guerrilla warfare where […], they are waiting until I’m down and out and vulnerable, weak, and then they will attack’ (V7) and feelings of suicidal ideation ‘the worst thing is to feel that self-destructive sort of “oh, I’ve got a solution for all this, I will just end it”’ (V7). Conversely, however, one participant described his ability to not listen to the voices as resulting from mental strength. When asked how he could ignore the voices, he explained: ‘it’s just from mental strength … having a strong mind, being sure of yourself’ (V11).

Discussion

This study identified 21 reasons for listening to and believing derogatory and threatening voices from patient interviews. Reasons were diverse and included aspects related to the self (e.g. emotional state, self-confidence), to the voice itself (e.g. its identity and the acoustic experience) as well as an overall drive to understand the experience. Whilst some reasons have been previously identified as important aspects of the voice-hearing experience, for example voice identity (Chadwick and Birchwood, Reference Chadwick and Birchwood1994), acoustic properties (McCarthy-Jones et al., Reference McCarthy-Jones, Trauer, Mackinnon, Sims, Thomas and Copolov2014; Moritz and Larøi, Reference Moritz and Larøi2008; Nayani and David, Reference Nayani and David1996) and aspects of the self (Thomas et al., Reference Thomas, Farhall and Shawyer2015), other factors, for example, a drive to understand the voice, and the specific threat appraisals were novel.

Patients described that listening to DTV content led to them feeling depressed and anxious. In addition, all participants discussed self-harm or suicidal ideation despite not being asked directly about this. Clinical interventions that enable the patient to distance their attention from and challenge such detrimental voice content should be of benefit. However, to shift attention away from the content, our view is that clinicians will need to consider the sorts of reasons for listening to DTVs identified in this study. The range of reasons includes modifiable cognitions that can be addressed through CBT interventions. For example, the appraisal ‘I listen to stop the voices harming other people’ can readily be addressed via behavioural experiments which test the impact of listening versus distancing responses on the feared outcome. However, other themes (e.g. to understand the voice) may require alternative approaches or further treatment development work. Irrespective, the therapist sharing a list of reasons why these voices can be so believable and difficult to ignore can guide a therapist in working with the patient to build up a more thorough, detailed and efficient formulation of the problem of listening to and believing malevolent voices.

There are limitations to the current study. The most severe DTV presentations are not represented because several acutely unwell patients approached in this study said they were unable to talk about their experiences. In addition, people not in touch with clinical services and those experiencing DTVs in diagnoses other than non-affective psychoses may offer alternative perspectives.

The problem of being consumed by believable DTVs resonated with patients and reasons were readily identified in interviews. The study is a first step in developing a theory about reasons for listening to and believing DTVs. The clear next step is to develop assessment measures to assess key concepts in this approach. This will allow the emerging theory to be refined and tested using quantitative methods.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000429

Acknowledgements

We are enormously grateful to the participants who shared their stories as part of this research. We thank Rachel Temple and Tillie Cryer at the McPin Foundation for facilitating the lived experience consultation.

Ethical statement

All authors have abided by the ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct set out by the APA.

Conflicts of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Financial support

B.S. is supported by an NIHR clinical doctoral fellowship (ICA-CDRF-2017-03-088), which funded the current study. L.I. is supported by an NIHR clinical doctoral fellowship (ICA-CDRF-2016-02-069). D.F. is supported by an NIHR Research Professorship (NIHR-RP-2014-05-003). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR, or the Department of Health and Social Care. L.J. is employed by Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.