The New Book Chronicle has covered a vast array of themes in recent years, from antiquarians to innovations, taking in connectivity, cities and empires along the way, but ‘art’ has seldom featured. The sometimes uneasy relationship between art and archaeology has been under the archaeological spotlight of late, from the recent focus on ‘Celtic art’ as a proxy for broader societal change (Gosden et al. Reference Gosden, Hommel and Nimura2016), to rethinking the theoretical underpinning of Palaeolithic art (Palacio-Pérez 2010). With a recent influx of books relating to Classical art on the Antiquity reviews shelf, it is perhaps pertinent to consider the state of such studies in the area that supports so much of our interpretation of the Classical world. As incoming reviews editor, with a background in Classical and Byzantine archaeology, it also allows me to revisit some of the subjects that inspired my own career in archaeology.

Despite art's often ambiguous place in archaeology, one might ask what better way is there to understand society than through its visual culture? Yet such an understanding largely depends on the approach that is taken. The books we look at in this NBC vary in the focus of their period and media, but common themes emerge that feature heavily in current studies of art. Challenging ourselves to find new ways of looking at art and in turn to reconceptualise how we understand art's place in social discourse is certainly a shared aim among the authors of our first two books.

Draycott, Catherine M., Raja, Rubina, Welch, Katherine & Wootton, William T. (ed.). 2018. Visual histories of the Classical world: essays in honour of R.R.R. Smith (Studies in Classical Archaeology 4). Turnhout: Brepols; 978-2-503-57632-9 €140.

Cormack, R.. 2018. Byzantine art (2nd edition). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 978-01978-7879-0 £19.99.

Classicist and archaeologist R.R.R. ‘Bert’ Smith arguably shifted Classical art into the mainstream as a lens for understanding ancient history. Challenging the traditional approach to art as divorced from its setting and independent of its maker, owner or commissioner, he has pioneered new ways of understanding art as inseparable from its context. Smith's work does not limit art to a standalone subject, and instead challenges the way that public architecture of cities such as Aphrodisias is understood, through art and visual culture. Aside from honouring Smith and recording the impact of his contribution, Visual histories of the Classical world aims to highlight the diverse areas that have been influenced by his work. Papers range in their focus from Archaic Greece to Late Antiquity, taking in the whole Mediterranean and a selection of provinces of the Roman Empire.

The book is divided into 10 sections that address key themes and periods, including case studies of particular objects, which highlight methods of best practice when approaching visual evidence. Caspar Meyer's paper in the ‘Approaches, methods and materials’ section, for example, challenges traditional and prosaic explanations for the discard of objects, which are based in binary understandings of objects as either gift or commodity. Instead, Meyer suggests we understand ownership as a process through which the biography of an object, its fluctuating value and the subtleties of the intrinsic power of objects can be read. Figural, verbal and decorative aspects are layers of complexity to be read and understood in the appearance of an object, and through these visual qualities, objects might fulfil roles as “social agents” (p. 44). The volume also includes essays on the ways in which historical phenomena can be visible in, and read through, visual remains. Anna Leone's paper on the social and economic significance of the use of statuary in Late Antique North Africa is one example, in which she explores the third- and fourth-century rise in refurbishment activity in private houses and what the reuse of statuary in this process can reveal about North African society. Another is Esen Ogus's consideration of why emblematic representations of individuals took the place of naturalistic depiction in Late Antiquity. Ogus investigates style, historical circumstances, power relations and the perception of statues to understand the increasing disparity between the man (the discussion centres on the male image) and his portrait. The difference, we learn, is due to the increasing use of stylistic traits to emphasise good qualities that gradually became emblematic of the power of an individual. Freedom from naturalistic concerns and increasing use of symbolic qualities led to a disconnect between the male body and its representation.

Of course, Smith's work at Aphrodisias is well represented, with one of the sections devoted to ‘Aphrodisias and Aphrodisians’. In this section, papers investigate: statuary in context (Julia Lenaghan); the sculptor's workshop (Julie Van Voorhis) and earthquakes (Andrew Wilson). The latter are explored in light of how they affected the monumentality of the city and indeed how far earthquakes can be considered to explain the end of classical monumental urban life in Asia Minor. Further papers examine the cemetery of Bingeç (Christopher Ratté) and a new inscription (Angelos Chaniotis). The volume includes a short personal note by Katherine Welch revealing the joys and challenges of studying with Bert Smith and a bibliography of Smith's work. With 41 papers and over 360 beautifully reproduced illustrations, this excellent book demonstrates the vibrancy of current scholarship on classical art and certainly reflects Smith's enormous contribution to the discipline.

Robin Cormack also encourages us to revisit the way that we think about the context of Byzantine art in his volume of the same name. Written for the Oxford History of Art series, and now in its second edition, Byzantine art takes a broadly chronological approach from which he draws out important themes. ‘Rethinking Byzantine art’ represents a new section for the second edition, in which Cormack revisits the assumptions and thinking on art that informed the first edition. The new section appears at the end of the book as an epilogue, but should really be read first to brief the reader on the reasoning that shapes the rest of the volume. Cormack draws a distinction between his art-historical approach, singling out significant and often high-status pieces, and assessing art as a material culture. Cormack deals deftly with the exploration of a huge subject in a relatively slim volume. He addresses variously: the complexities of reading Byzantine art as a product of a transformation of the Roman Empire; the nature of Byzantium as a faith culture and how traditional views of Byzantine society as intensely and predominantly religious shape our understanding of its art, and why an overestimation of this might mislead us in our interpretation of how society functioned in practice. The disconnect between art and text is also investigated in terms of how manuscripts can aid (or hinder) the interpretation of art. This represents a major challenge for Byzantinists, not least because of the tendency for texts to focus on personalities and the opportunity that provides for hyperbole, polemic and other bias. Text are used judiciously in Byzantine art as Cormack believes “processes rather than individuals like the emperor were the key agencies for change in the state” (p. 205).

The volume begins with a discussion of what constitutes Byzantine art; this considers the dominance of religious imagery in the genre, the geographic scope traditionally attributed to it and the timelessness of Byzantine art, which arguably outlived the society after which it is named. The chapters then follow the broad chronological periods of the Byzantine Empire with sections devoted to the sixth century AD and some of the most recognisable examples of Byzantine art from the Justinianic era—St Sophia, Ravenna and the Barberini Ivory; the seventh to ninth centuries focusing on iconoclasm and the response to the rise of Islam; and Middle Byzantine art with its revival of icons and influence from the West. A chapter focused on the new spirituality of the eleventh century addresses how church art became associated with the imperial image and considers the dissemination of artistic trends between centre and periphery and whether this model is a sustainable way to understand the movement of ideas. The final chapter explores Late Byzantine art, ‘Westernisation’ and the impact of a clash of Orthodox and Catholic theology. The book is peppered with information boxes offering concise explanations of subjects that are beyond the scope of the text but crucial to the subject: ‘The Orthodox church’, ‘How to date a dated inscription’ and ‘How to paint an icon’. Eminently readable, well illustrated and supported by a timeline detailing key historical events, imperial reigns and the most significant visual arts, this volume is an excellent way to understand the fluidity of Byzantine art and the importance of how we read it.

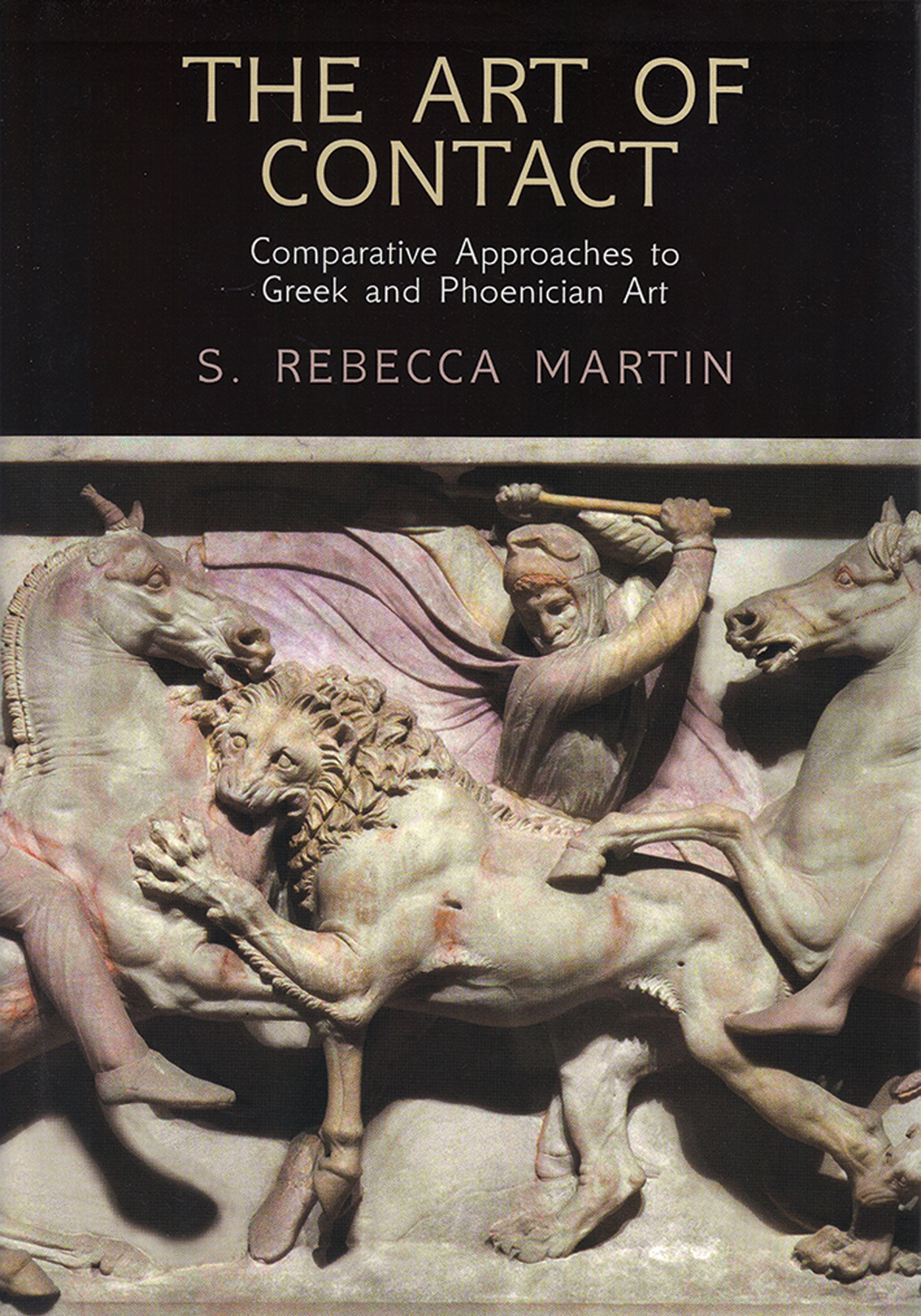

Martin, S. Rebecca. 2017. The art of contact: comparative approaches to Greek and Phoenician art. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 978-0-8122-4908-8 £50.

Elsner, Jaś. 2018. The art of the Roman Empire AD 100–450. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 978-0-19-876863-0 £19.99.

Another theme that looms large in the study of visual culture is the place of art in culture contact, the art that emerges when societies interact and identities are reinforced, reinterpreted or reshaped. This phenomenon is a focus, to a greater or lesser extent, for our next two volumes. Greek-Phoenician art studies have traditionally focused on ‘culture contact’, the idea that physical proximity may result in mutual influence. Familiar and—as S. Rebecca Martin sees it—flawed themes in this vein are ‘Orientalising’ and ‘Hellenisation’. Martin sets out to challenge the dominance of Hellenisation, arguing that the traditional Hellenocentric approach does not address the agency of human actors or objects and assumes limited or no impact on the Greeks and Greek culture from other societies. Beginning with a robust critique of the centre-periphery model of Hellenisation and the premise that current models for understanding ancient history are plagued by “misleading primordialist narratives” (p. 4) Martin sets out to show the ways in which a re-evaluation of art can enhance our understanding of Greek and Phoenician identities and the interrelationship between the two cultures. Starting from the premise that art is a key tool for understanding Greek-Phoenician contact, the book uses select examples of art as case studies to challenge and deconstruct existing dichotomies, terminology and ideas that currently shape the field of study. Martin's approach values the ‘other’ in terms of the contribution Phoenician culture makes to the understanding of contact, rather than privileging Greek sources.

The chapters run by theme and are broadly chronological. Each presents a self-contained methodological study striking a balance between detail and readability. Taken together, the chapters gradually marshal evidence to demonstrate that the ways in which art is affected by interaction are not fully explained by current approaches. The individual studies include an interesting comparison between the iconic Greek kouros (a sculptural representation of the male form) and the picture mosaic—typified by examples such as floor mosaics from Morgantina and Pella—in which Martin exposes the dualism in approaches to arts of contact. The two genres are traditionally evaluated in completely opposite ways. The focus of studies of kouroi have emphasised the importance of the location of manufacture and display over the stylistic origins; conversely, studies of mosaic have prized motif and stylistic origins over the site of production and presentation. The case study highlights the extent to which conventions of interpretation shape perceptions of art and how much these can be, and indeed are, influenced by the prominence of the ancient Greek world in modern scholarship. Other chapters chart the rise of Phoenician art by evaluating statues, epigraphy and sarcophagi to demonstrate that the emergence of Phoenicianism in material form did not happen until the Persian and Hellenistic periods; these chapters also consider the concept of hybridity through a reappraisal of the iconic Alexander Sarcophagus.

Martin does not propose a new overarching theory to shape the study of Greek and Phoenician art, but rather calls for a greater awareness of existing theoretical approaches (the volume is influenced by the work of Alfred Gell) in the understanding of ancient art. The take-away messages from this volume are: that ‘barbarians matter’; that Greek art and Phonecian art should be ‘contested spaces’; that critical use of theory should continually be used in studies of art to challenge the way we understand Mediterranean art history; that contact art is critical to understanding expressions of identity; and that influence is a two-way phenomenon.

In another volume from the Oxford History of Art series, Jaś Elsner's accessible approach to the arts of the Second Sophistic (the Greek cultural movement of the first to third centuries AD) and Late Antiquity provides a thoughtful and compact guide to key themes in the study of the visual arts. Tackling a leviathan subject through a synchronic and thematic treatment allows the reader to dip in and out without losing context. The book is divided into four parts, the first three dealing with the overarching themes of power, society and transformation, followed by the fourth in the form of an epilogue that considers some of the economic aspects of art including artists’ earnings and the value of art. The volume considers the big themes in art such as: images and power; imperial imagery; centre and periphery; and death and the expression of identity through art. Despite clearly signposted themes for each section, chapters are nicely nuanced so that themes do not dominate, and the objects are allowed to tell their own stories without being shoe-horned into the narrative of any particular theme. While Elsner is self-critical about the burgeoning weight of public and imperial artworks over smaller private pieces, the selection appears very well balanced, as does the geographic range.

The main difference from the first edition is the addition of a new chapter investigating the movement of Roman art to the east and the influence of Asian material and visual culture on the Roman world. Here Elsner picks up themes that we have seen in Martin's Art of contact. The implications for this cultural mixing form the basis for the new chapter: ‘The Eurasian context’. This deals with the appropriation of visual culture and images and the interconnectedness of artistic culture. Throughout Roman visual culture, external foreigners, or ‘the other’, are frequently depicted alongside the multiple cultures that were subsumed under the rule of the empire. Foreigners were often depicted as vanquished foes of Rome, and this motif in turn was borrowed and expressed in other cultures. Similar templates of conqueror and vanquished appear, for example, in the reliefs cut into the rock below the tomb of Darius at Naqsh-e Rostam, where the depiction of two Roman Emperors humbled before the mounted Persian Shah (Shapur) draw parallels between his victories and those of Darius the Great.

The economic and physical aspects of art are also investigated here; much of the material that adorned Roman art was imported from beyond the frontiers. Jewels for imperial crowns, elephant ivory for diptychs and the incense that staged the visual and sensorial performance of the Christian liturgy all had to be acquired from elsewhere. The result is a complex map of an interconnected material cultural network demonstrating the consumption in the Mediterranean of products from far beyond the empire, as distant as China and India.

The examples are supported throughout by Graeco-Roman sources to enhance the interpretation of reception and cultural context. Clearly in the same vein as Visual histories of the Classical world, The art of the Roman Empire privileges the ways in which visual imagery was integral to social construction.

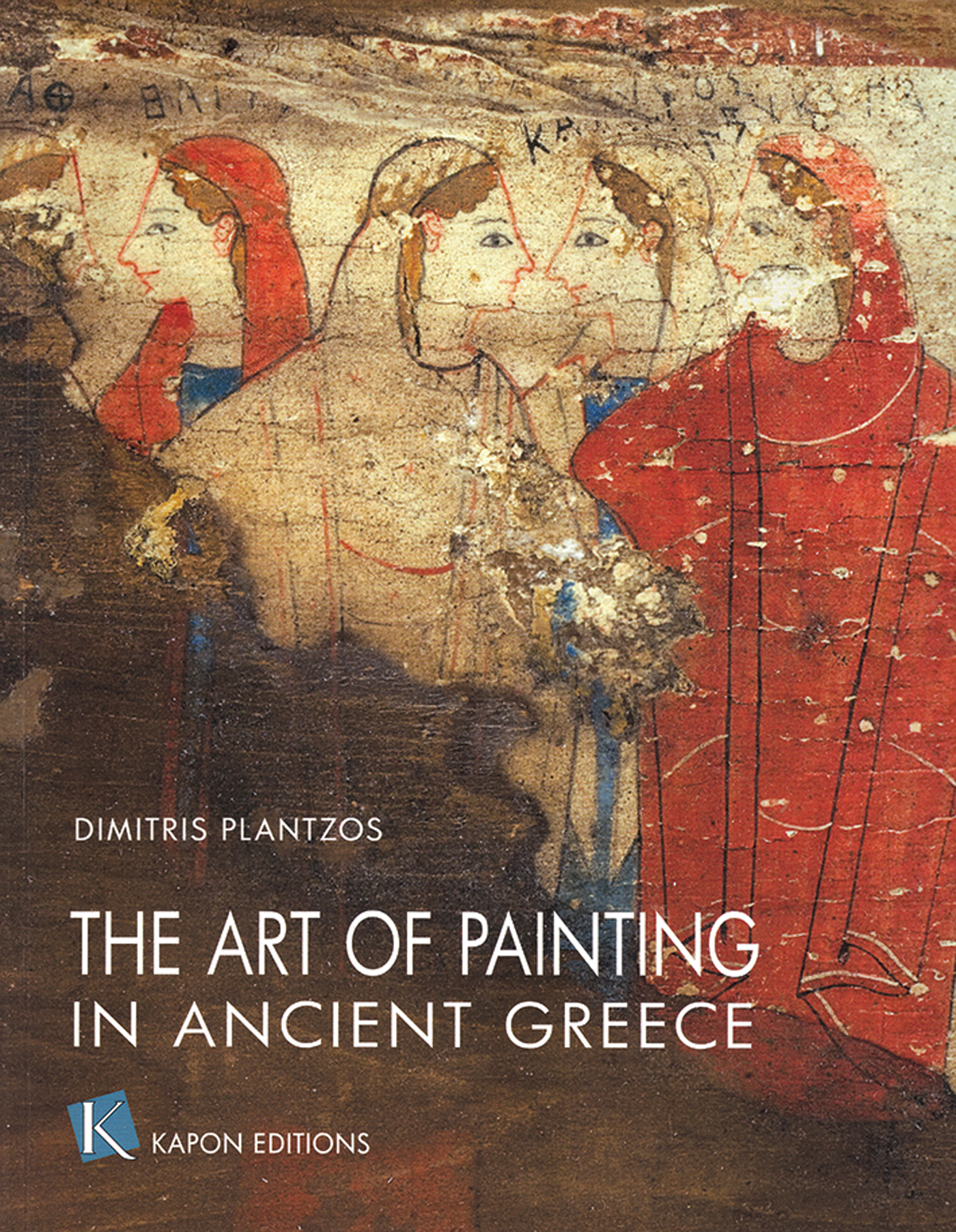

Plantzos, Dimitris. 2018. The art of painting in ancient Greece. Athens: Kapon; 978-618-5209-20-9 €47.60.

Our final book highlights the ways that the different mediums of visual culture, and particularly its manufacture, can be understood. Dimitris Plantzos's glossy and colourful volume sets out to investigate the history of depiction in ancient Greece. This is framed within the developments of painting from the seventh century BC to the Late Hellenistic period. The book is informed with examples situated in their archaeological and cultural context, and supported where possible by literary evidence, but the approach is not as driven by agency and theory as the methodologies of Visual histories of the Classical world and The art of contact. The book draws a distinction between painting on pottery—which it considers a lowlier form of art through its association with craftsmen labouring in workshops—and wall or panel painting whereby images were painted either onto a wall surface or a wooden panel. While drawing stylistic comparisons with the former, this study is focused on the latter ‘monumental’ technique, which was considered a noble pursuit and something that should be part of the accomplished Greek man's cultural repertoire.

Beginning with an assessment of the sources and methodology, techniques and materials and the state of current scholarship, the volume takes a chronological journey through the techniques of tetrachromy and shadow-painting, the ‘Greek gaze’, verisimilitude and the illusion of three-dimensional space, and portraiture. The unexpected inclusion of a section on mosaics draws out interesting questions on the influence of monumental painting on the craft of the mosaicist, with parallels drawn between the tonal gradation and shadowing techniques of the freehand painter and the careful choice of coloured tesserae by the mosaicist to achieve similar effects. The book covers quite a time span, beginning in the Greek Bronze Age with early Cycladic forerunners, and ending up in the Villa Boscoreale in first-century AD Pompeii. Along the way we learn of the importance of literacy in the appreciation of Greek art with the synoptic or multitemporal technique that requires the viewer to be educated in mythology and Homeric literature; art in the staging of drama; and the debated origin of skenographia. A significant theme, particularly from the Hellenistic period onwards, is the use of portraiture, used frequently on grave markers. The portrayal of individuals in this way, especially in relation to their deaths is well illustrated in a study of painted grave markers. Some of the highlights of this study are Hellenistic tombstones from Alexandria and Demetrias showing women who had died in childbirth. The images show the women post-mortem and are filled with sentiments of grief. This bucks the trend for depicting the deceased alive in an idealised portrayal of life. While Plantzos explains that this kind of depiction would have been unthinkable before the shifts in religious and social thinking of the Hellenistic period (and in fact they never became the norm), we are left wishing that this phenomenon had been explored more fully to understand why death in childbirth might merit full and frank depiction, while death in war, for example, did not.

It is clear from these volumes that art is increasingly part of mainstream archaeological discourse and can no longer be treated as a distinct area of study. Classical archaeology, once considered somewhat lacking in theoretical orientation (Johnson Reference Johnson1999), is now demonstrating its engagement with concepts of agency, the biography of objects and cultural contact perspectives, which are transforming the very essence of how we perceive the role of art in past societies.

Books received

This list includes all books received between 1 November 2018 and 31 December 2018. Those featuring at the beginning of New Book Chronicle have, however, not been duplicated in this list. The listing of a book in this chronicle does not preclude its subsequent review in Antiquity.