Analysis of 89 European Iron Age glass objects from the Mathay-Mandeure Celtic sanctuary in Doubs, France, has led to the discovery of seven previously unnoticed La Tène engraved glass beads. Evidence for the Late Iron Age working of cold glass is extremely rare, with only a single Celtic engraved glass bead known from the Müsingen-Rain cemetery in Switzerland (Gambari & Kaenel Reference Gambari and Kaenel2001). Examination and elemental analysis of the objects increases our understanding of the depositional practices carried out at the Mathay-Mandeure sanctuary. The discovery also encourages greater attention to the potential of glass beads as a medium for bearing engravings.

Excavations carried out by Clément Duvernoy (Reference Duvernoy1883) at the monumental sanctuary of ‘Clos du Château’ between 1882 and 1883 yielded almost a tonne of melted Gaulish coins. This prompted a series of unofficial excavations, particularly by local antiquarian Aimé Péquignet. Beneath a Roman landfill level, Aimé Péquignet discovered a large pit containing many artefacts. Although glass items predominated, the assemblage also contained iron objects, bronze ornaments (including two zoomorphic figurines), coins, ceramic vessels and gold artefacts. Of the glass finds, 356 beads, 147 bracelets and a dozen other items are now housed in the National Museum of Archaeology in Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

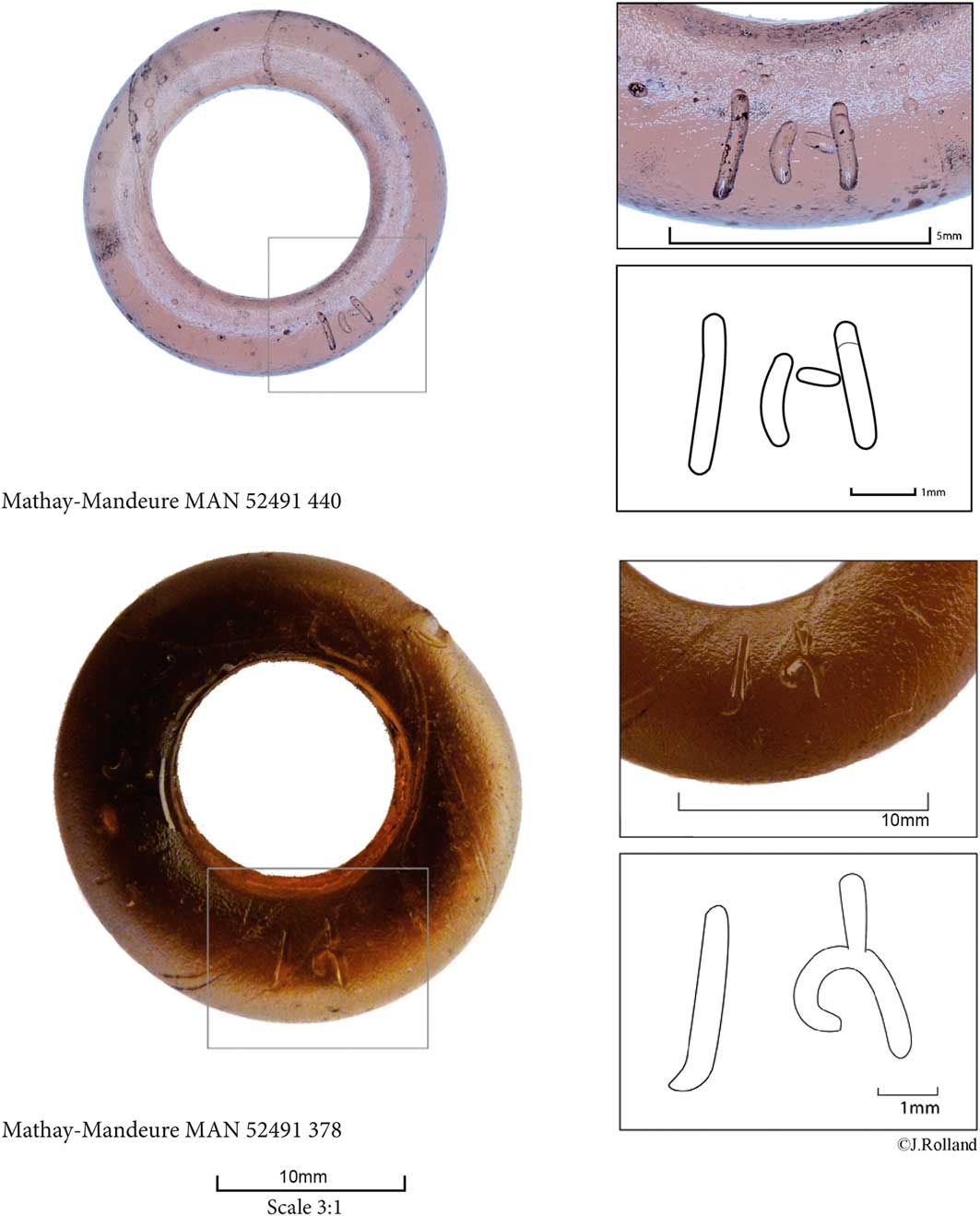

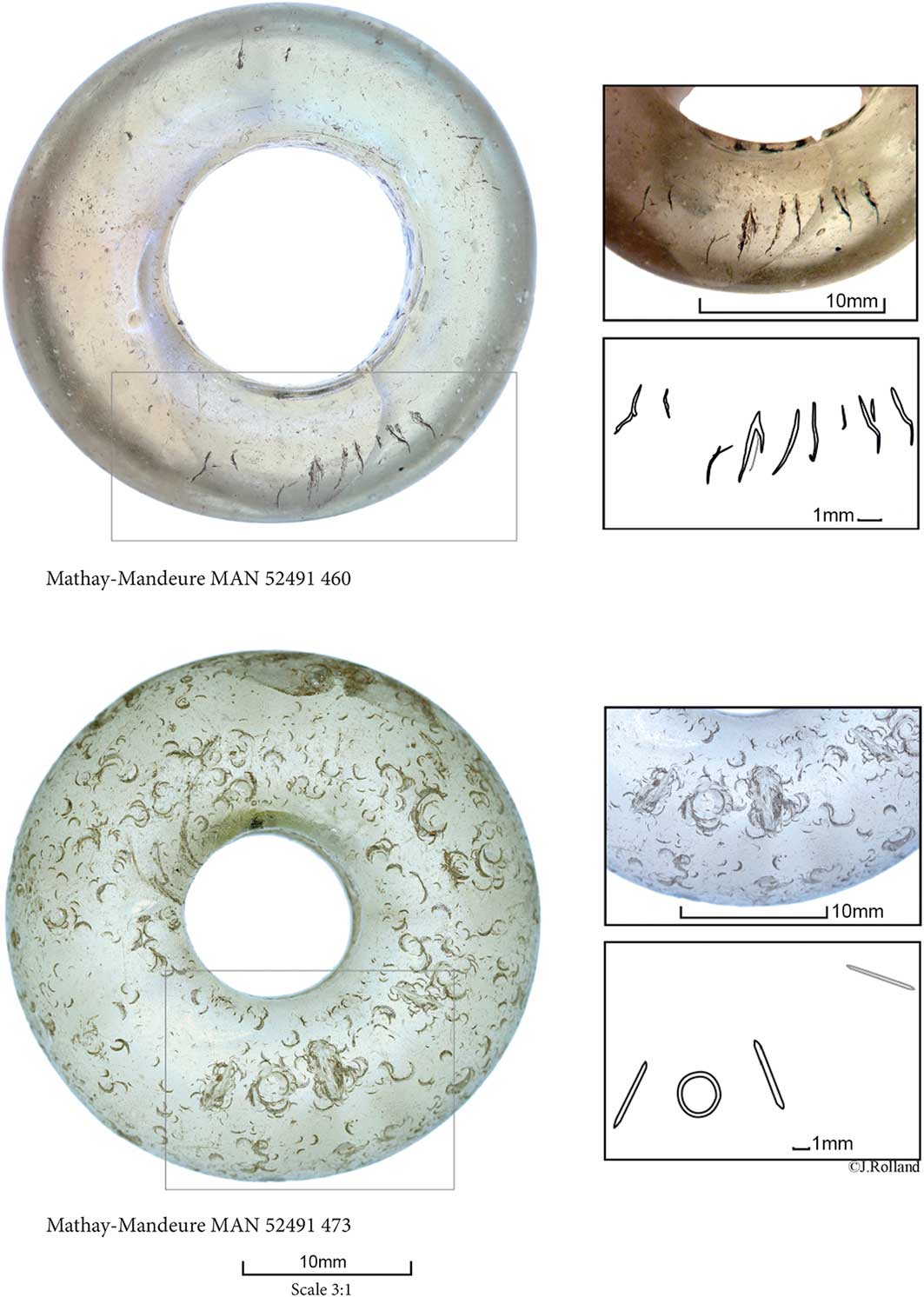

The glass assemblage is composite in nature, comprising a mixture of worn glass objects, dating from the La Tène C2 period (200–150 BC) and homogeneous sets of La Tène D period (150–25 BC) beads (Guillard Reference Guillard1989; Bride Reference Bride2000; Barral Reference Barral2009). In terms of form, the similarity of these La Tène D bead sets is such that some of them were probably made at the same time, by the same craftsperson. The absence of wear traces on these sets suggests a very short interval between their manufacture and their deposition. The composite nature of the deposit is also observed on the seven engraved beads. The two amber and purple glass beads (52491.378 and .440) are characteristic of the La Tène D period (Haevernick Reference Haevernick1960; Gebhard Reference Gebhard1989) (Figure 1). The remaining colourless beads can be divided into four different types, according to their profile shape and the presence of an inner layer of yellow glass (Figures 2–4). These types were produced at the end of the La Tène C2 period, but also during the La Tène D period. Our elemental analysis, however, has allowed us to refine the chronology for the manufacture of these beads further.

Figure 1 Engraved beads n° 52491.440 and .378 from the Mathay-Mandeure sanctuary (National Museum of Archaeology in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, images by J. Rolland).

Figure 2 Engraved beads n° 52491.460 and .473 from the Mathay-Mandeure sanctuary (National Museum of Archaeology in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, images by J. Rolland).

Figure 3 Engraved beads n° 52491.465 and .475 from the Mathay-Mandeure sanctuary (National Museum of Archaeology in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, images by J. Rolland).

Figure 4 Top) engraved beads n° 52491.464 from the Mathay-Mandeure sanctuary; bottom) the seven engraved beads (National Museum of Archaeology in Saint-Germain-en-Laye, images by J. Rolland).

To identify major, minor and trace elements (Gratuze Reference Gratuze2016), the seven engraved beads from Mathay-Mandeure were analysed using a LA-ICP-MS (mass spectrometer) at the CNRS, IRAMAT/CEB, in Orleans, France. Analysis reveals that all samples comprise soda-lime glass, using a mineral source—Natron—as the soda flux (Figure 5). Published data (Karwowski Reference Karwowski2004) and recent results (Rolland Reference Rolland2017) show that La Tène C2- and La Tène D-period mineral-natron glass is characterised mainly by low zirconium and high strontium contents, the mark of the Levantine origin of the sands used (Nenna & Gratuze Reference Nenna and Gratuze2009; Rolland Reference Rolland2017). Furthermore, the manganese content of all La Tène glass generally increased over time (Huisman et al. Reference Huisman, Van Der Laan, Davies, Van Os, Roymans, Fermin and Karwowski2017; Rolland Reference Rolland2017). The lower manganese content of bead 52491.473 from Mathay-Mandeure suggests that it could be the oldest of the seven. Covered with traces of wear, this bead was probably worn before its deposition (Figure 2). The engraving on the bead, however, resembles those on beads 52491.378, .440 and .475. Therefore, while bead .473 appears to have been manufactured at an earlier date, the engraving was probably added at the same time as the other engravings—perhaps specifically for the purpose of deposition.

Figure 5 Average compositions of the engraved beads expressed in oxide weight percentage.

The Mandeure deposit and the presence of glass objects in other sanctuary contexts suggest that these valuable objects were discarded as part of ostentatious social practices. As with the glass bead from the Müsingen-Rain cemetery, the Mandeure engravings appear to use a Lepontic or Insubro-Lepontic script. The deciphering of such engravings will undoubtedly open interesting avenues for future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Bernard Gratuze for his collaboration in the analysis of the beads, and Thomas Markey for his research on the inscriptions.