Antimicrobial use (AU) tracking is a critical component of any antimicrobial stewardship program (ASP). Reference Barlam, Cosgrove and Abbo1 Initially developed in 2015 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the standardized antimicrobial administration ratio (SAAR) is an AU measure that has potential to allow for national benchmarking and interfacility comparison. Reference O’Leary, Edwards and Srinivasan2 Thousands of hospitals have voluntarily submitted data to the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) Antimicrobial Use and Resistance (AUR) Option, Reference O’Leary, Edwards and Srinivasan2 and we believe that the SAAR has significant promise as a public health and stewardship tool. However, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) has announced that beginning in 2024, all acute-care hospitals and critical-access hospitals will be required to report to the NHSN AUR module. 3 In light of this change, our commentary is meant to caution against public reporting and inclusion in value-based programs tied to reimbursement. Rushing the measure to have consequences for hospital reimbursement before it is ready risks unintended consequences, including a forced redistribution of limited resources, and may be harmful to hospitals and ultimately, patient care. We critique the SAAR and offer past examples of similarly flawed measures used for public reporting without an adequate evidence base.

The SAAR

The SAAR is similar to the more well-established standardized infection ratio (SIR) used to track healthcare-associated infections (HAIs). Similarities include the use of an observed-to-predicted framework to guide facilities. However, a critical difference is that while the optimal number of HAIs is zero, the optimal amount of antibiotic use is unknown. Antibiotics are lifesaving medications to patients with severe infections. The ideal amount of antibiotic use is an elusive benchmark because it can be variable by setting and patient and is, to some degree, subjective. Reference Spivak, Cosgrove and Srinivasan4 Most inpatient ASPs determine appropriate use through some amount of chart audit and feedback, which allows for incorporation of individual clinical scenarios and patient-level variables in decision making. Developing a risk-adjusted SAAR for national benchmarking is a laudable goal, but for ASPs to be able to use it constructively, the details matter.

SAAR is not a single metric but a multifaceted one. The SAAR creates a metric for adult, pediatric, and neonatal populations using 17 patient location types across 22 antimicrobial agent categories. This framework results in 47 possible SAARs (Appendix 1). 5 Certainly, variability in antimicrobial utilization would be expected between these types of units. However, a vast difference of expected use may remain even within these unit types, limiting the value in comparison. For example, a “hematology oncology” unit that cares primarily for solid-tumor cancer patients would have significantly different expected antibiotic use from one that cares primarily for hematologic malignancies with stem-cell transplant patients, where antimicrobial prophylaxis may be appropriate and where neutropenic fever is common. Similarly, in some facilities, solid-organ transplant units may be categorized as any of the ward types, and expected antimicrobial use would undoubtedly differ from similarly categorized wards that do not care for such patients. Although a facility stewardship program with specific knowledge of each of their units may be able to use the SAAR for internal benchmarking and initiatives, the absence of this level of detail would make broader comparisons at the regional, state, or national level of limited value. More importantly, a move toward pay for performance with financial penalties for higher-than-expected use, without such adjustments, would be a disservice to those facilities caring for more vulnerable patients and may increase disparities by income and race. Stewardship in immunocompromised patients is an important and growing area of focus, Reference So, Hand and Forrest6 and peer comparison with similar units or facilities may be valuable for those caring for such patients. However, the SAAR requires further refinement to allow for such comparisons. Reference So, Nakamachi and Thursky7

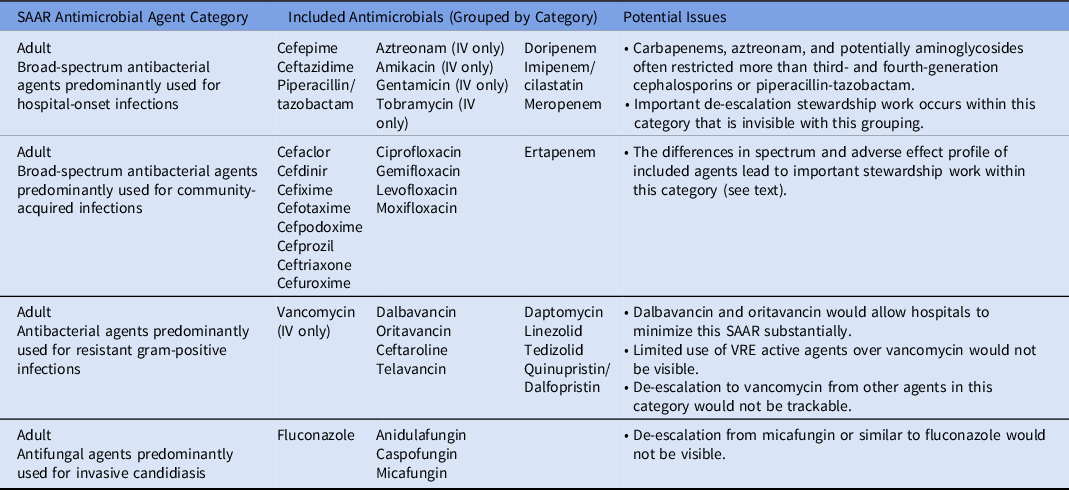

Beyond the lack of granularity of location types, the current SAAR antimicrobial groupings are similarly too broad to allow for meaningful tracking or comparison. For example, ertapenem and fluoroquinolones are grouped with cefuroxime and ceftriaxone under “adult broad-spectrum antibacterial agents predominantly used for community-acquired infections.” Important stewardship work for community-acquired intra-abdominal infections may include promotion of second- or third-generation cephalosporin use plus metronidazole and discouragement of fluoroquinolone use (due to higher resistance expected for the typical pathogens and the adverse effect profile) and of ertapenem use (given lack of need for need for such broad coverage in most locations). However, such work would be invisible within the current SAAR categorization. Worse, de-escalation from ertapenem would actually increase the “all antibacterial agents” SAAR. Under threat of financial penalties, it is not difficult to imagine a facility moving from ceftriaxone and metronidazole to ertapenem for such infections, which would improve their SAAR but would be worse for patient care, selection of resistance, and overall cost of care. There are similar potential issues in other SAAR antimicrobial groupings (Table 1).

Table 1. Selected Standardized Antimicrobial Administration Ratio (SAAR) Antimicrobial Groupings and Potential Issues

Note. SAAR, standardized antimicrobial administration ratio; IV, intravenous; VRE, vancomycin-resistant enterococci.

To further demonstrate the need for risk adjustment, consider a region in which the community rate of ESBL Enterobacterales is high enough to warrant empiric ertapenem for community-acquired intra-abdominal infections. Even if antimicrobial grouping is rectified in future SAAR iterations, to appropriately compare facilities regarding expected antimicrobial utilization, antimicrobial resistance data would need to be considered. This analysis may be possible with the requirement of submission to the Antimicrobial Resistance Option, and preliminary investigations into utilization of antimicrobial resistance data have been done. Reference Santos, Martinez and Won8 However, any pay-for-performance initiative designed prior to its inclusion would be premature.

Importantly, the SAAR does not adjust for any patient-level factors. Patient-level data are needed to appropriately benchmark antimicrobial utilization. Reference Yu, Moisan and Tartof9 Because inclusion of patient-level variables can substantially influence how hospitals rank, Reference Goodman, Pineles and Magder10 further research into which patient-level variables should be included is necessary to guide further refinement of the SAAR before any consideration of public reporting or using such data for reimbursement. Such refinement is being considered by the CDC. Reference O’Leary, Edwards and Srinivasan2

Finally, feasibility of mandated reporting must also be considered. Smaller-to-midsize community facilities often have fewer financial resources, lower content expertise, and less information technology capability to facilitate the required reporting. Lack of time, technical support, and salary support are known barriers for AUR reporting. Reference Werth, Dilworth and Escobar11 Critical-access hospitals, which voluntarily report to the AU option at a lower percentage compared to all hospitals, Reference O’Leary, Edwards and Srinivasan2 will be required to report to NHSN by 2024. 3 Although the CMS has delayed implementation of AUR reporting by a year from the previously proposed 2023, they estimate a median cost of $187,400 to purchase or build an AUR reporting solution. 3 Especially for smaller facilities who do not already have this in place, mandating reporting by 2024 remains an aggressive timeline with considerable financial and administrative barriers.

The slippery slope

Premature requirement of infectious disease metric reporting has occurred in the past, with negative impacts on patients. In 2004, The Joint Commission instituted a core measure for community-acquired pneumonia that included requirements for drawing blood cultures as well as administration of antibiotics within 4 hours of arrival at the emergency department. Reference Walls and Resnick12 These measures, which were publicly reported and linked to reimbursement, led to unnecessary blood-culture ordering (the routine use of which may lead to false-positive results, unnecessary antibiotics, and increased length of stay Reference Metlay, Waterer and Long13 ) that continued despite revisions to the measure to limit use to a sicker subset of patients. Reference Makam, Auerbach and Steinman14 They also led to unnecessary antibiotic administration by emergency physicians to meet the metric. Reference Nicks, Manthey and Fitch15 Not supported by high-quality evidence, Reference Wilson and Schünemann16 the pneumonia measure has since been retired.

Similarly, adherence to the Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock Early Management Bundle (SEP-1), implemented by the CMS in 2015, has not led to improved patient outcomes, Reference Baghdadi, Brook and Uslan17,Reference Barbash, Davis, Yabes, Seymour, Angus and Kahn18 but these data continue to be required and publicly reported. Citing concerns of antibiotic overuse, the Infectious Diseases Society of America, with the support of the American College of Emergency Physicians, American Hospital Association, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society, Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America, Society of Hospital Medicine, and Society of Infectious Diseases Pharmacists, has called for major revisions to the measure. Reference Rhee, Chiotos and Cosgrove19 Although well intended, these examples should serve as warnings that national requirements that precede a firm evidence base can lead to wasteful or harmful patient care and unnecessary administrative burden. Mandated reporting of AU data to the NHSN is one step closer to mandated public reporting and use of the SAAR for financial penalties to hospitals, for which it is not nearly ready.

In summary, we applaud the CDC for continued exploration of the SAAR as a risk-adjusted, validated AU metric available for national benchmarking. However, the SAAR is not ready for mandatory use. It needs granularity and risk adjustment for the metric to improve antibiotic use. The CDC is aware of many of these limitations to the SAAR and has highlighted the potential for improvements in future iterations. Reference O’Leary, Edwards and Srinivasan2 With AUR reporting now mandated by the CMS by 2024, we caution policy makers not to go further by requiring public reporting or inclusion of SAAR metrics in value-based programs because doing so prematurely could lead to significant unintended financial and, more importantly, patient safety consequences.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2023.143

Acknowledgments

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Conflicts of interest

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.