No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

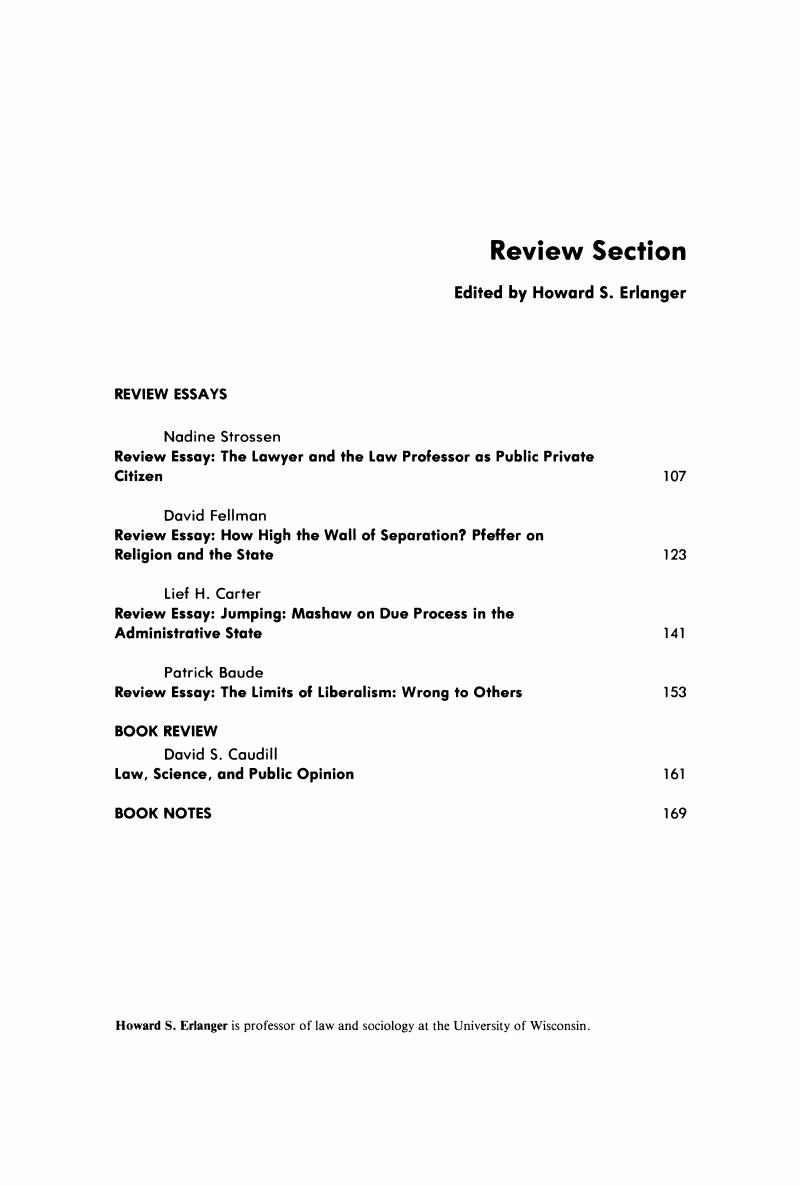

The Lawyer and the Law Professor as Public Private Citizen

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 November 2018

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essay

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Bar Foundation, 1986

References

1 Mason, Brandeis: A Free Man's Life (1946).Google Scholar

2 Friendly, Book Review, 56 Yale L.J. 423, 426 (1947);Kaplan, Book Review, 60 Harv. L. Rev. 165, 169 (1946).Google Scholar

3 See, e.g., Ulman, , Book Review, 47 Harv. L. Rev. 735, 735 (1934). See also French, Book Review, 170 Law & Soc. Ord. 167, 170 (1970) (author, former law clerk to Justice Frankfurter, recalls his saying that “when he taught students about constitutional law, he taught the biographies of the justices”).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

4 See H. Abraham, Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court 338 app. A(2d ed. 1984) (65 scholars rate Brandeis and Frankfurter as 2 of 12 “great” justices). See also Friendly, Learned Hand: An Expression from the Second Circuit, 29 Brooklyn L. Rev. 6, 7 (1962) (rates Brandeis as one of four greatest American judges of first half of twentieth century).Google Scholar

5 See, e.g., L. Baker, Felix Frankfurter (1969); P. Kurland, Mr. Justice Frankfurter and the Constitution (1971); A. Todd, Justice on Trial (1964); M. Urofsky, A Mind of One Piece: Brandeis and American Reform (1971). See also books cited infra note 6. One scholar of history and American studies recently observed: “Brandeis may enjoy the honor of having drawn more biographers than any other modern American public figure.”Murphy, , Book Review, 1984 Wis. L. Rev. 1391, 1391 (1984).Google Scholar

6 See N. Dawson, Louis D. Brandeis, Felix Frankfurter and the New Deal (1980); A. Gal, Brandeis of Boston (1980); H. N. Hirsch, The Enigma of Felix Frankfurter (1981); T. McCraw, Prophets of Regulation: Charles Francis Adams, Louis D. Brandeis, James M. Landis, and Alfred E. Kahn (1984); B. Murphy, The Brandeis/Frankfurter Connection: The Secret Political Activities of Two Supreme Court Justices (1982); L. Paper, Brandeis: An Intimate Biography of One of America's Truly Great Supreme Court Justices (1983); M. Parrish, Felix Frankfurter and His Times (1982); M. Silverstein, Constitutional Faiths: Felix Frankfurter, Hugo Black, and the Process of Judicial Decision Making (1984); M. Urofsky, Louis D. Brandeis and the Progressive Tradition (1981).Google Scholar

7 See, e.g., Letters of Louis D. Brandeis, ed. M. Urofsky & D. Levy. 5 vols. (1971-78).Google Scholar

8 In 1917, Brandeis established in a Boston bank a “Joint Endeavors for the Public Good” account on which Frankfurter could draw. From 1917 through 1925, Brandeis deposited a total of $4,500 in this account in irregular installments. From 1926 until Frankfurter's appointment to the Court in 1939, Brandeis contributed $3,500 per year to the account. In addition to reimbursing Frankfurter for expenses incurred in his public interest activities, these funds were intended to supplement Frankfurter's personal income and to help defray the costs of psychiatric care required by Frankfurter's wife, Marion. Frankfurter had discussed with Brandeis the possibility of supplementing his professorial salary through private legal work in order to meet these costs. Brandeis, however, insisted on providing the necessary funds himself, explaining: “Your public service must not be abridged. Marion knows that Alice [Mrs. Brandeis] and I look upon you as half brother, half son” (Baker at 243). See infra note 46.Google Scholar

9 For example, Murphy contends that Brandeis's financial support to Frankfurter was conceived from the beginning as “a long-term lobbying effort” (Murphy, supra note 6, at 40) in which Frankfurter would be Brandeis's “paid political lobbyist and lieutenant”(id. at 10). See Schlesinger, An Ideological Retainer, N.Y. Times, Mar. 21, 1982, § 7 (Book Review) at 5 (Murphy conveys “the impression of a sinister Bran-deis-Frankfurter conspiracy to run national affairs from the highest judicial bench”). Notwithstanding his book's pervasive innuendos, Murphy does not directly answer the two questions he proposes for evaluating the propriety of Brandeis's and Frankfurter's extrajudicial conduct: (1) whether they adhered to their own standards of propriety, and (2) whether they adhered to the standards of their judicial colleagues and predecessors. Even Murphy seems to acknowledge that the first question should be answered affirmatively, at least regarding Brandeis (Murphy, supra note 6, at 33), and there is much support for an affirmative answer to the second question as well. See, e.g, Danelski, Book Review, 96 Harv. L. Rev. 312, 323–27 (1982); Frank, Book Review, 32 J. Legal Educ. 432,438-44 (1982). Murphy's ultimate judgment is that Brandeis's financial assistance played “no significant part in [Frankfurter's] decision to do what he did,” and that both men were “forces for good” (at 342). In an earlier study, Murphy concluded even more clearly that Brandeis acted strictly in accordance with his acute sense of judicial propriety and that, through their joint efforts, both men made significant contributions to liberal causes. See Levy & Murphy, Preserving the Progressive Spirit in a Conservative Time: The Joint Reform Efforts of Justice Brandeis and Professor Frankfurter, 1916–1933, 78 Mich. L. Rev. 1252, 1302–3 (1980): There is no evidence that Brandeis, despite his normal sensitivity to the requirements of judicial propriety, was much troubled by the questions raised by his relationship with Frankfurter…. Certainly Brandeis never regarded Frankfurter as a mere “employee,” nor could he objectively do so. Brandeis never asked the professor to undertake projects or to act on suggestions that did not command Frankfurter's independent approval and allegiance…. No shred of evidence survives to suggest that Brandeis ever asked Frankfurter to perform tasks intended to enhance Brandeis's personal reputation, increase his financial holdings, or discredit some persona] opponent. This nobility of purpose—as Brandeis perceived it—must have gone a long way toward quieting any nagging doubts about the propriety of the arrangement. Whatever verdict is rendered on the matter of judicial propriety, one conclusion remains clear: for sixteen years, in an environment of social and political conservatism, Louis D. Brandeis and Felix Frankfurter had combined their efforts to further a wide range of traditional, progressive causes…. The surprising thing … is not that they did not always achieve their purposes, but that two individuals were able to accomplish so much…. Brandeis and Frankfurter played a substantial role in preserving the spirit of American liberalism during he intervening years [between the first years of the century and the reform movement of the 1930s].Google Scholar

10 Relying on the theories of Erik Erikson and Karen Homey, Hirsch diagnoses Frankfurter as having suffered a prolonged crisis concerning his Jewish identity, which led to an inflated, idealized self-image.Google Scholar

11 See, e.g., Cover, The Framing of Justice Brandeis, New Republic, May 5, 1982, at 17, 21 (book contains “shoddy scholarship and commercial exploitation,” resulting in “a scandal-mongering distortion”); Kurland, “Brandeis-Frankfurter” Sensationalizes Serious Issue, Legal Times, Apr. 12, 1982, at 10 (scholarly contribution flawed by melodramatic tone); Resnik, Book Review, 71 Calif. L. Rev. 776, 794 (1983) (Murphy employs “careless history and provocative prose”); Schlesinger, supra note 9 (criticizes book's suggestion of conspiracy through its language, subtitle, and jacket illustration depicting Brandeis and Frankfurter as “villains in a Hitchcock movie”); Wheeler, Book Review, 81 Mich. L. Rev. 931, 932 (1983) (Murphy presents his interpretations “as conclusive when his facts merely create an arguable case for them”).Google Scholar

12 See, e.g., Dorsen, Book Review, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 367, 372–74 (1981) (book manifests author's personal hostility toward Frankfurter); Stone, Book Review, 95 Harv. L. Rev. 346 (1981) (criticizes Hirsch's psychological analysis).Google Scholar

13 See, e.g., Friendly, supra note 2, at 426 (in Mason's 1946 Brandeis biography “the adulatory note is a little too strongly struck”); Dorsen, supra note 12, at 376 n.35 (“With few exceptions, contemporaneous scholarly commentary on Justice Frankfurter, usually written by former students or law clerks, tended to be flattering and uncritical”). See also Marcus, Book Review, 95 Yale L.J. 195, 204 (1985): “The hagiographic view of Brandeis began during his lifetime with the publication in 1936 of Alfred Lief's biography, Brandeis: The Personal History of an American Ideal.Google Scholar

14 Baker specifically refutes a number of assertions in Murphy's book. See Baker at 244, 384, 413.Google Scholar

15 Accord, e.g., Danelski, supra note 9, at 325: “From Brandeis'perspective, financing Frankfurter's public interest work was not at all wrong; indeed it was to Brandeis positively right—a contribution to the betterment of society. His code of propriety concerning his assistance to Frankfurter and to social causes generally [while on the Supreme Court] was… that he do no more than‘(1) to think on the main problems of the cause; (2) to give moral support; and (3) to give financial support’” (quoting letter from Brandeis to Jacob de Haas, dated Mar. 28, 1928). Brandeis's financial assistance to Frankfurter was also consistent with his munificent financial contributions to numerous organizations and other individuals whose work he supported. Between 1890 and 1939, when there were no tax incentives for charitable gifts, Brandeis donated $1 million to organizations, and $500,000 to friends and relatives. Moreover, he sometimes suggested that people who owed him money donate the loaned sum to charity instead of repaying him (Baker at 242). The individual beneficiaries of Brandeis's financial assistance included other law professors. See Frank, supra note 9, at 436 (“He contributed, for example, funds to both Wilbur Katz, later Dean of the University of Chicago Law School, and James Landis, later Dean at Harvard, to help the work in which they were engaged”).Google Scholar

16 Strum also refutes Allon Gal's theory (see A. Gal, supra note 6, at ix, 76) that Brandeis was driven to Zionism by his exclusion from Boston Brahmin society. She finds no evidence that Brandeis was rejected by Boston's upper classes because of his religion. To the contrary, Strum explains that Brandeis was initially well received by the Brahmins but subsequently fell into disfavor with them because of the progressive political and economic causes he espoused. Strum at 22 & n. 16, 29–30 & n.33, 225–29.Google Scholar

17 See introductory note supra.Google Scholar

18 Baker's emphasis on how U.S. anti-Semitism affected Brandeis and Frankfurter contrasts with Strum's downplaying of this subject. Strum largely dismisses the impact of anti-Semitism on Brandeis's life, concluding that his Judaism neither impeded his brilliant legal career in Brahmin-dominated Boston nor accounted for the fierce opposition to his Supreme Court nomination (Strum at 15–18, 293–95). Strum's deemphasis of anti-Semitism is at least partly attributable to the fact that American anti-Semitism was less pronounced during Brandeis's young adulthood than during Frankfurter's (Baker at 71–72). Also, consistent with Strum's overall focus on Brandeis's Zionism and other political beliefs, she attributes the hostility he faced following his Supreme Court nomination and at other points in his career not to his Jewish heritage but rather to his Zionist and other political beliefs (see, e.g., 226, 236, 294). In contrast, Baker points to specific instances of anti-Semitism that directly affected Brandeis: he quotes the opinion of Brandeis's law partner, who represented him during the Senate hearings on his Supreme Court nomination, that anti-Semitism was a major factor underlying the vitriolic opposition (at 102); cites certain anti-Semitic attacks on Brandeis's character when he was being considered for Wood-row Wilson's cabinet (at 86); notes that following Brandeis's Supreme Court appointment he had trouble finding housing in Washington because of anti-Semitism (at 182); and points to the snubbing he received from his fellow justice, James McReynolds, an avowed anti-Semite (at 370 and notes accompanying photographs on third page following 216).Google Scholar

19 Brandeis's parents emigrated to the United States from Germany in 1849. He was born in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1856. See, e.g., Strum at xviii, 1.Google Scholar

20 Frankfurter emigrated to the United States from Vienna with his parents when he was 12 years old. When he arrived in this country, he “never had heard a word of English spoken and never had spoken an English word … not one word!” H. Phillips, Felix Frankfurter Reminisces 4 (1960).Google Scholar

21 The great American Zionist leader Rabbi Stephen Wise ranked Brandeis with Chaim Weizmann, the first president of Israel, as the two individuals who did the most to create a Jewish state (Baker at 75). Baker concludes that Frankfurter also deserved to be called “a father of the Jewish development in Palestine” (at 291–92).Google Scholar

22 See, e.g., Danzig, , Justice Frankfurter's Opinions in the Flag Salute Cases: Blending Logic and Psychologic in Constitutional Decisionmaking, 36 Stan. L. Rev. 675, 695–99 (1984). According to Danzig, Frankfurter “believed that assimilation could be made compatible with a distinctive ethnic and religious identity by insisting on the irrelevance of” the latter for professional and public purposes. Id. at 696. Frankfurter therefore refused to hide his Jewish background. For example, Frankfurter rejected the suggestion of the hiring partner at a Wall Street firm, where he sought to work following his law school graduation, that he change his name. Although the partner thought Frankfurter's decision was “very foolish,” Frankfurter became the first Jewish lawyer employed by the firm. Phillips, supra note 20, at 36–39; Baker at 63. Nonetheless, Frankfurter's adamant belief that his Jewish background was irrelevant to his professional and public identity contrasts sharply with Brandeis's staunch belief in the fusion of his two roles as a Jewish patriot and an American one. See, e.g., Strum at 258; Baker at 79.Google Scholar

23 See, e.g., Danzig, supra note 22.Google Scholar

24 West Virginia Bd. of Educ. v. Barnette, 319 U.S. 624, 646 (1943) (Frankfurter, J., dissenting); Minersville School Dist. v. Gobitis, 310 U.S. 586, 591 (1940) (Frankfurter, J., writing for majority).Google Scholar

25 Phillips, supra note 20, at 37. Professor Hirsch explains Frankfurter's Zionist undertakings as ‘“a defense of Jews, as human beings, against genocide, persecution and discrimination; it was never an attempt, consciously at least, to perpetuate Jewish identity.’” Hirsch, supra note 6, at 219 n. 129 (quoting D. Hollinger, Morris R. Cohen and the Scientific Ideal 212 (1975)).Google Scholar

26 Phillips, supra note 20, at 38.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

27 See generally Levy & Murphy, supra note 9. Fully living up to Dean Acheson's description of him as an “incurable optimist” (Strum at 329), Brandeis believed that individual liberty—which, according to Strum (at x), he valued more highly than anything else—would in the long run be strengthened even by actions that curtailed it in the short run. For example, responding to one assault on civil liberties, Brandeis counseled: “By such follies is liberty made to grow, for the love of it is reawakened. Of course there are growing pains; but with the throes come also the joys of the struggle and of creation” (Baker at 255, quoting Brandeis's note to Zechariah Chafee).Google Scholar

28 Thomas, , Book Review, 13 Revs. Am. Hist. 94, 104 (1985).Google Scholar

29 See also Baker at 367, 396, 491; note 32 infra & accompanying text.Google Scholar

30 See, e.g., Danzig, supra note 22, at 706–10.Google Scholar

31 See, e.g., id. at 698–700.Google Scholar

32 See, e.g., Phillips, supra note 20, at 17–19, 26–27. For example, Frankfurter stated: “I have a quasi-religious feeling about the Harvard Law School. I regard it as the most democratic institution 1 know anything about. By ‘democratic’ I mean regard for the intrinsic and for nothing else.”Id. at 19.Google Scholar

33 Thus, in criticizing Brandeis's political ideology, the socialist philosopher Morris Cohen delcared that, for some individuals, “to be let alone” by the government was not, as Brandeis had proclaimed in his famous Olmstead dissent, “the greatest right,” but to the contrary, “the worst calamity.”Cohen, , Book Review, 47 Harv. L. Rev. 165, 167 (1933). Compare Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438,478 (1928) (Brandeis, J., dissenting): “[The Fourth and Fifth Amendments] conferred, as against the government, the right to be let alone—the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.”.Google Scholar

34 277 U.S. at 485. The high status that Brandeis accorded to education was also reflected in his view that government could not impinge on education in the absence of a clear and present danger. See, e.g., Strum at 322. Brandeis also believed that individual citizens have the responsibility to “educate” government officials concerning individual rights through all available means, including lobbying and litigation. Deeply disturbed by the governmental invasions of civil and political liberties during World War I and its aftermath, Brandeis wrote to Frankfurter in June 1926: “I think the failure to attempt such redress as against government officials for the multitude of invasions… is also as disgraceful as the illegal acts of the government… in enacting the statutes…. Americans should be reminded of the duty to litigate.” Letter to Felix Frankfurter (June 25, 1926), reprinted in 5 Letters of Louis D. Brandeis, supra note 7, at 225–26. Consonant with this encouragement, Frankfurter was one of the founders and early leaders of the American Civil Liberties Union, which was dedicated to seeking redress against governmental infringements of individual freedoms (Baker at 253).Google Scholar

35 See, e.g., Danzig, supra note 22, at 683.Google Scholar

36 Cited supra note 24.Google Scholar

37 Frankfurter's majority opinion in the earlier of those cases, Minersville School Dist. v. Gobitis, was seen by some contemporary observers as reflecting his especially heightened patriotism following the Nazi invasion of France, and was accordingly dubbed “Felix's Fall of France opinion.” See, e.g., Frank, supra note 9, at 442.Google Scholar

38 See, e.g., Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234, 255 (1957) (concurring opinion) (academic freedom precludes state attorney general from investigating political affiliations of state university instructor); Illinois ex ret. McCollumv. Boardof Educ, 333 U.S. 203 (1948) (establishment clause bars provision of religious instruction on public school premises during school hours to children who choose to receive it).Google Scholar

39 Oliver Wendell Holmes had pioneered this innovation, and Brandeis was one of the first justices to follow suit.Google Scholar

40 See, e.g., Hutchinson, Felix Frankfurter and the Business of the Supreme Court, O.T. 1946-O.T. 1961, 1980 Sup. Ct. Rev. 143, 164–203.Google Scholar

41 See, e.g., Levy & Murphy, supra note 9. The hostile response to the causes that Brandeis had championed surfaced most clearly during the bitter struggle to confirm his Supreme Court nomination. See, e.g., Baker at 98–115. Although Frankfurter's Supreme Court nomination did not arouse any serious opposition, Frankfurter's liberal activism had previously evoked strong opposition. See, e.g., Baker at 150, 260, 363–64.Google Scholar

42 After several years on the Court, Brandeis declined Robert M. La Follette's invitation to become his running mate in the 1924 presidential election (Strum at 157).Google Scholar

43 Brandeis represented many important clients, including major businesses, and became very wealthy. See, e.g., Strum at 226 (by 1914, Brandeis was “the best-known lawyer in the United States, and by far one of the richest”).Google Scholar

44 As a Harvard Law School faculty member, Frankfurter was a dynamic teacher as well as a prodigious and influential scholar. See, e.g., Baker at 225–28 (quoting Frankfurter's students regarding his stimulating and demanding teaching style); Dorsen, supra note 12, at 368 & n.5 (Frankfurter wrote “a series of important books and law review articles” and “was a major stimulant of new ideas”).Google Scholar

45 Brandeis's view that he could “best serve the people” as a “public private citizen” (Strum at 204) was shared by others. For example, when Brandeis was approached to run for the position of Massachusetts governor or U.S. senator, one newspaper commented:'’ As a private citizen he weighs more than a carload of Murray Cranes [Massachusetts governor and U.S. senator]. Anyone who has ever heard him … must realize how little the senatorial toga would add to the stature of a real statesman, patriot and lover of his kind” (Strum at 205).Google Scholar

46 Baker offers no theory for reconciling Frankfurter's adamant refusal to accept compensation from public interest clients with his eventual acceptance of what he initially refused also—Brandeis's stipends to support this work. See supra note 8. Perhaps by the time Brandeis began to make regular payments to Frankfurter's account, Frankfurter was more in need of money because of his wife's deteriorating health. See, e.g., Baker at 241–42.Google Scholar

47 See also id. at 225.Google Scholar

48 See Stone, supra note 12, at 347.Google Scholar

49 Brandeis initially struggled in choosing between an academic career and private practice (Strum at 360). He at first leaned toward academia, because of “the almost ridiculous pleasure which the invention of a legal theory gives me” (Baker at 25). However, he ultimately decided that he wanted “to become known as a practicing lawyer”(id. at 26). Nevertheless, Brandeis did teach evidence at the Harvard Law School from 1882 to 1883, and he also taught business law at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology from 1892 to 1894. See, e.g., Strum at 35–37.Google Scholar

50 See, e.g., Levy, & Murphy, , supra note 9, at 1291–96; Freund, Mr. Justice Brandeis: A Centennial Memoir, 70 Harv. L. Rev. 769, 769–75 (1957).Google Scholar

51 Warren, & Brandeis, , The Right to Privacy, 4 Harv. L. Rev. 193 (189091). Regarding the importance of that article, see, e.g., Strum at 37–38 (Harvard Law School Dean Roscoe Pound later stated that it “did nothing less than add a chapter to our law”); Kalven, , Privacy in Tort Law—Were Warren and Brandeis Wrong? 31 Law&Contemp. Probs. 326, 327 (1966) (refers to the Warren and Brandeis article as “that most influential law review article of all”); Siegel, Privacy: Control Over Stimulus Input, Stimulus Output, and Self-regarding Conduct, 33 Buffalo L. Rev. 35, 38 (1984) (describes article as “the singular prominent example of the potential for the legal academic community to influence courts”).Google Scholar

52 See, e.g., Rauh, , Felix Frankfurter: Civil Libertarian, 11 Harv. Civ. Rts.-Civ. Lib. L. Rev. 496, 498–501 (1976).Google Scholar

53 See, e.g., J. Lash, From the Diaries of Felix Frankfurter 39 (1975).Google Scholar