Introduction

In France, as in many other countries, Alzheimer's disease embodies the ‘archetypical figure of “ageing going badly”’ (Ngatcha-Ribert Reference Ngatcha-Ribert2012: 7). Following changes in its medical categorisation and through the combined actions of health professionals, the media and families’ associations, Alzheimer's disease has gradually emerged as a major social issue, leading public authorities to make it a priority concern. In France, for example, Alzheimer's disease became a major public policy issue in the 2000s, leading to the creation of an ‘Alzheimers and related disorders’ plan (2008–2012) that received significant financial support under the presidency of Nicolas Sarkozy.Footnote 1

Alzheimer's disease's public exposure was accompanied by the construction of a very sombre imagery. The family and friends of people with Alzheimer's disease have been described as collateral victims of the illness, weighed down by the ‘burden’ of care (Zarit, Orr and Zarit Reference Zarit, Orr and Zarit1985) and exhausted by the magnitude of the tasks they have to assume. At the same time, people with the disease were seen as having lost the core of their humanity – their memory and ability to reason – condemning them to identity loss and a zombie-like state (Behuniak Reference Behuniak2011). More fundamentally, in a ‘hypercognitive’ culture and society that emphasises people's powers of rational thinking and memory (Post Reference Post1995), people suffering from Alzheimer's disease tend to represent radical alterity. Also, ageing with Alzheimer's disease is considered to be a form of ageing apart today, in contrast to contemporary norms of ‘active ageing’, ‘successful ageing’ or ‘ageing well’. This negative image of people with Alzheimer's disease is relatively uniform, since the category of ‘Alzheimer's sufferer’ tends to obfuscate all differences. People are only considered in terms of their cognitive deficit and are reduced to an attributed illness-based identity, the assumption being that their disease is in an advanced stage.

Of course, these representations are unsatisfactory for the social sciences, which have sought an alternative perspective on the illness through the development of particular methodologies and analytical tools. Methodologically, researchers study the experience of people with Alzheimer's disease directly through their narratives and accounts in order to understand the lived experience of the illness, and re-situate these experiences in context. Research conducted in the United States of America, the United Kingdom and, more recently, in France has gradually included the long-neglected viewpoint of people with Alzheimer's disease, at least those in the early stages who are able to speak about their experience (Cotrell and Schulz Reference Cotrell and Schulz1993; Cowdell Reference Cowdell2008; Downs Reference Downs1997). Several studies have explored daily life with the illness (MacRae Reference MacRae2008), how threats to identity are managed (Beard Reference Beard2004; Clare Reference Clare2002, 2003), the tension between acceptance and denial (Macquarrie Reference Macquarrie2005), and the connections between identity maintenance and narrative processes (Bouchard Ryan, Bannister and Anas Reference Bouchard, Bannister and Anas2009; Hyden and Örulv Reference Hyden and Örulv2009). This research focuses on how people with Alzheimer's disease confront it and sometimes fight back, ‘making the best you can of it’ or declaring ‘we'll fight it as long as we can’ (Clare Reference Clare2002).

In addition to detailed description of the strategies employed, sociological research focusing on the lived experience of people with Alzheimer's disease has two major strengths. The first is that it shatters the uniform image of the experience of the illness: Hulko (Reference Hulko2009) demonstrates that having Alzheimer's disease may be experienced as a great drama or it may not be, emphasising the variability of an experience ‘ranging from “not a big deal” to “hellish”’. Such research also demonstrates the gap between the usual representations of the illness and the actual experience of people afflicted with it, for whom it is not always a disaster, some relativising their difficulties and managing to preserve their identity (Beard Reference Beard2004; Chamahian and Caradec Reference Chamahian and Caradec2014; Clare Reference Clare2002; MacRae Reference MacRae2008). The second strength of this approach is that it considers the illness from a perspective other than the physiological. The illness is seen as part of a context that simultaneously provides an interpretive template and the resources for confronting it (Downs Reference Downs2000; Kitwood Reference Kitwood1990; Lyman Reference Lyman1989). This context is first and foremost socio-historical and cultural: depending on the era and culture, cognitive difficulties can be thought of as challenges inherent to ageing whose dramatisation would serve no point, as in China (Lupu Reference Lupu2009), or as symptoms of a specific cognitive pathology requiring diagnosis and treatment, as in western societies today. The context also includes the social background of sufferers, as Hulko (Reference Hulko2009: 136) has demonstrated in the observation that Alzheimer's disease is less tolerable among higher social class groups, where identity tends to be formed around cognitive performance. Lifecourse experiences are also part of the context, as shown in Lichtenberg's (Reference Lichtenberg2009) observation that African Americans are faced with more risk factors for developing dementia over the course of their lives, especially poor childhood nutrition. Lastly, the extent and quality of the social environment of people with Alzheimer's disease are significant (Chamahian and Caradec Reference Chamahian and Caradec2014; Kitwood and Bredin Reference Kitwood and Bredin1992; Surr Reference Surr2006).

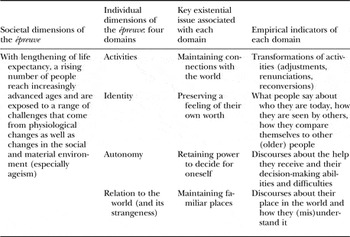

This paper builds on the sociological perspectives of the research cited above, but in a specific way, since its aim is to examine the épreuve (literally translated as ‘challenge’) of ageing with Alzheimer's disease. The concept of épreuve was formulated by French sociologist Danilo Martuccelli, who was inspired by Sartre's existential philosophy, phenomenological sociology and its concern for analysing modern experiences, and Charles Wright Mills’ assertion that it is necessary to ‘connect personal problems and the social structures that generate or amplify them’ (Martuccelli and de Singly Reference Martuccelli and Singly de2009: 73). Martuccelli holds that a society can be characterised by the épreuves it presents to the individuals composing it, ‘historical, socially produced, unequally distributed épreuves that individuals are forced to confront’ (Martuccelli Reference Martuccelli2006: 12). This concept has been used by French sociologists of ageing to characterise the épreuve of ageing based on research conducted with people without cognitive problems. They have identified four domains of épreuve: activities, identity, autonomy and relationship to the world (Caradec Reference Caradec2007). This paper aims to apply this template to research conducted with people with Alzheimer's disease. It demonstrates how people with Alzheimer's disease experience changes in their relationship to themselves and the world and aims to understand the extent to which their ageing experience differs from that of people without the illness and whether these changes alter the épreuve of ageing.

We first introduce the template for analysing the épreuve of ageing and its four domains. This is followed by a presentation of our study on the experience of people with Alzheimer's disease. Lastly, we evaluate how well this épreuve of ageing template applies to our corpus.

Background

Over the past 20 years, French sociologists have been influenced by theoretical approaches that give increasing attention to individuals and their experiences (Martuccelli and de Singly Reference Martuccelli and Singly de2009), chief among them Berger and Luckmann's constructivism, Schütz's phenomenological psychology, and Beck and Giddens’ theories of individualisation. In the field of social gerontology this trend is evident in a body of research aiming to account for the process and experience of individual ageing. Some French scholars have focused on transitions related to ageing, such as retirement or being a widow(er), analysed using the concept of identity (Caradec Reference Caradec2004). Other studies (Barthe, Clément and Drulhe Reference Barthe, Clément and Drulhe1988; Clément and Membrado Reference Clément, Membrado and Carbonnelle2010; Mallon Reference Mallon2004) have elaborated the concept of déprise, designating the process of converting one's life to overcome or compensate for difficulties linked to the ageing process. More recently, Caradec has proposed gathering prior research contributions under Martuccelli's concept of épreuve (Caradec Reference Caradec2007; Martuccelli Reference Martuccelli2006). Since individuals are forced to confront historically, socially produced and unequally distributed épreuves, the concept is thus an analytical operator where the macro- and micro-sociological levels meet: the épreuves have both a societal dimension (since it is the social context that gives them form) and an individual dimension (since they are felt by individuals, and differently according to their resources).

This perspective prompts us to argue that contemporary western societies oblige a growing number of individuals to confront a range of challenges by allowing them to reach an increasingly advanced age. These challenges come from physiological changes (health problems, functional limitations, accumulating fatigue) and changes in the social and material environment (the death of peers, family and friends’ increased anxiety and attention due to their growing old, a more hostile outside world where older people are considered burdensome and face a variety of forms of ageism). They vary according to social class, and are part of what could be called the ‘épreuve of ageing’, leading to gradual changes in how people reconstruct their identities and relate to the world. These changes can be sorted into four domains, each touching on a central existential issue for ageing: the domain of activities draws attention to the issue of preserving connections with the world; the domain of identity refers to the way that older people try to preserve a feeling of their own worth; the domain of autonomy raises the question of retaining power to decide for oneself; and the domain of the relationship to the world (and its strangeness) broaches the issue of maintaining places familiar to the ageing person. Table 1 presents the épreuve of ageing template; we will develop each domain in greater detail in the text that follows.

Table 1. Template of the épreuve of ageing

The first is the domain of everyday activities. Because of the aforementioned challenges, with advancing age it may become difficult to pursue certain activities. Ageing people are consequently in a process of reorganising their lives under an increasing number of constraints, going through a series of adjustments, renunciations and reconversions. As previously mentioned, French sociologists have called this phenomenon déprise. Although the French term is reminiscent of disengagement (Cumming and Henry Reference Cumming and Henry1961), there are at least four differences between them. Firstly, the theory of déprise does not stop with the observation that certain activities are abandoned with the advancement of age, going on to emphasise that some activities are retained, abandoned activities may be replaced by others, and certain activities may be voluntarily set aside in order to ‘hold on to’ others, following the principle of the ‘economy of strength’ (Clément and Membrado Reference Clément, Membrado and Carbonnelle2010: 118). Secondly, whereas disengagement was presented as an inevitable process, déprise is a probabilist phenomenon that prompts changes in habits which are increasingly likely to appear as age advances, but they may also not arise. Thirdly, déprise recognises that individuals have the capacity for action: when confronted with challenges, people deploy strategies according to the extent of their ability to adapt. From this perspective, the concept of déprise has a degree of family resemblance with ‘selective optimization with compensation’ (Baltes and Cartensen Reference Baltes and Cartensen1996), which also emphasises strategies for adapting to ageing. Its aims are wider, though, since it envisages ageing not only in its successes (the ability to adapt to new limitations) but also in its more negative dimensions (giving up activities that the person was very attached to, which could be qualified as the ‘ultimate déprise’ (Clément and Mantovani Reference Clément and Mantovani1999). Consequently, déprise is a socially differentiated process, both because difficulties are unevenly distributed (as data on morbidity and disabilities attest) and because the deployed strategies depend on the resources available to individuals. Fourthly, the theory of déprise is not intended to offer a reading of ageing as external to individuals. On the contrary, it leads us to emphasise that one of the major existential issues for older people is continuing meaningful activities as long as possible, or put another way, preserving significant connections with the world.

The second domain is that of identity, the existential issue concerning ageing people's ability to preserve a feeling of social worth, which is likely to be challenged in a variety of ways. Research has shown that there are four aspects to identity in elders. The first is a tension between ‘being’ and ‘having been’: the issue is knowing the extent to which self-esteem can still be based on current engagements, or if people have no other solution than to base their social value in the past, in what they used to be and do (Caradec Reference Caradec2004). The second aspect refers to how ageing people manage others’ perceptions that reduce them to ‘old age’: can they manage to distance themselves from this view, or do they let themselves be closed in by it (de Beauvoir Reference de Beauvoir1972; Minichiello, Browne and Kendig Reference Minichiello, Browne and Kendig2000)? The third is related to the fact that older people's self-evaluation is also forged by how they compare themselves with others of the same age. From this perspective, the strategy of ‘downward contrast’, which is the comparison with someone judged to be less good than oneself, is by far the older person's most frequent comparison strategy (Beaumont and Kenealy Reference Beaumont and Kenealy2004). Lastly, the fourth concerns the way in which ageing individuals position themselves in relation to ageing: do they think they are getting old, or that they are old forever after (Balard Reference Balard2013; Caradec Reference Caradec2004; Cavalli and Henchoz Reference Cavalli, Henchoz, Oris, Widmer, de Ribaupierre, Joye, Spini, Labouvie-Vief and Falter2009)?

The third domain concerns the control that ageing people manage (or fail) to keep over their lives. Indeed the prevalence of functional limitations and activity restrictions increases with age (Cambois, Robine and Romieu Reference Cambois, Robine and Romieu2005), as does the risk of frailty or becoming dependent for activities of daily living (Guilley et al. Reference Guilley, Ghisletta, Armi, Berchtold, Lalive d'Epinay, Michel and de Ribaupierre2008; Lalive d‘Epinay and Spini Reference Lalive d'Epinay and Spini2008). Although we must remember that not all older people have functional limitations, an increasing number of them do need family or professional help to perform certain tasks as they age (shopping, house cleaning, personal care, etc.). The issue that arises is the maintenance of their ‘decisional autonomy’, or their ability to decide their own affairs when their ‘autonomy of execution’ declines, to use Collopy's (Reference Collopy1988) distinction. Existing research stresses that older people struggle to maintain their decisional autonomy, a fundamental value in contemporary western societies. They use a range of strategies to this end: hiding potentially worrying incidents – like falls – from their loved ones so that they will not intervene even more often; rejecting the home assistance social workers planned for them when they do not want them and their intervention chips away at their autonomy (Gucher et al. Reference Gucher, Alvarez, Chauveaud, Laforgue and Warin2011); for those living in a retirement home, protesting instructions about hygiene, food or medication, or refusing to participate in group activities (Mallon Reference Mallon2004: 147–56). We should add that another kind of figure emerges in some studies, albeit one sketched with less precision: people who develop a sort of indifference to things as they age, letting their family or professionals make decisions for them and thus delegating their autonomy (Collopy Reference Collopy1988; Membrado Reference Membrado1999).

The fourth and last domain is that of the relationship with the world. Indeed with advancing age there is a tendency to develop a feeling that the world is strange and foreign: the impression of having an increasingly difficult time understanding the society in which one lives, and being part of it. Older people could thus be thought of as paradigmatic figures of the gap between objective and subjective cultures that Simmel considered to be a major characteristic of modernity (Simmel Reference Simmel1968); put in other terms, they could be seen as ‘immigrants in time’ (Dowd Reference Dowd and Marshall1986). Among various statements from interviews or the journals of quite elderly writers (Argoud and Veysset Reference Argoud and Veysset1999), we cite an illustrative example from Claude Lévi-Strauss, who at the age of 96 declared, ‘we are in a world to which I already no longer belong. The one I knew, the one I loved, had 1.5 billion inhabitants. The current world has 6 billion humans. It's no longer mine’.Footnote 2 This difficulty in subscribing to current society is borne of multiple mechanisms. Abandoning activities that make people feel like they are still engaged with the world risks imposing an even greater distance from it. In parallel, the deaths of peers that lived through the same eras, who ‘could read your mind’ (Clément Reference Clément2000) and shared a degree of complicity, contribute greatly to this feeling. The same holds true for changes in the environment, such as technological developments or modifications in the urban environment that result in one becoming a stranger in one's own town or neighbourhood. Faced with this growing foreignness of the world, the existential issue is to maintain parallel familiar spaces. There are two general strategies that stand out. The first consists of fighting this feeling of strangeness, and some people adopt new technologies to be able to ‘stay with it’. The second strategy is to shut oneself into a close space, familiar and safe, that counter-balances the strangeness and insecurity of the outside world: ‘home’.

In conclusion, we emphasise that there are many ways of responding to the existential issues raised by these four domains. When facing the épreuve of ageing, resources are unequally distributed along two criteria. One is that resources come from the past, such as financial resources, health more or less preserved depending on the kind of work one did, and abilities to adapt resulting from educational levels and past experiences. The other is that they come from the present environment, which may offer more or less favourable support, be it relational or material, such as transportation and urban facilities.

In sum, the épreuve of ageing breaks down into four domains: activities, identity, autonomy and relationship to the world. It is important to remember that these domains have been designated on the basis of research with people without cognitive problems. The question now is whether it applies to people who are ageing with Alzheimer's disease.

Methods

Our corpus is composed of 27 interviews conducted with people attending the Memory Consultation Centre at the Regional University Hospital Centre (Centre Hospitalier Régional Universitaire) in Lille, France.Footnote 3 There were two criteria for inclusion in the sample. Firstly, we decided to interview only people who had been diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease and informed of the diagnosis. Consequently, we excluded other forms of neuro-degenerative dementia (vascular, Lewy body, fronto-temporal), since the goal was to assemble a diagnostically homogeneous population in order to be able to explore the variety of experiences. Secondly, our interviewees had to be capable of speaking coherently about their experience. We thus retained people in the ‘mild’ or ‘moderate’ stages of the illness based on their Folstein test scores (Mini-Mental State Examination; Folstein, Folstein and McHugh Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975) obtained through memory consultations. Most of our interviewees had a score at or superior to 20/30, and a few slightly below 20.

We next diversified the socio-demographic characteristics of our sample. It consisted of 11 women and 16 men, aged 52–92.Footnote 4 Nearly all lived at home (although one lived in a religious community and four in retirement homes). The majority of people we met (18) had left their professional activities several years previously, but some (two) were still professionally active and others’ (seven) work had been cut short following diagnosis, when they were put on disability benefits or retired. Concerning social positions, people in our corpus were mainly in the middle and upper classes, but just over a third (N = 10) were former labourers, basic employees or farmers. Lastly, we paid particular attention to domestic situations: 17 lived with a spouse or partner, six lived alone and four lived with one of their children. Although research was primarily with the ill people themselves, whom we tried to interview alone without family present, when possible we ended meetings by also speaking with a family member (a partner or a child).

Our resolutely qualitative methodological approach is inspired by the Weberian and Schützian traditions aiming to understand and reconstruct the social worlds experienced by individuals. It is an interpretive sociology (Angermüller Reference Angermüller2005) in which ‘comprehensive’ interviews (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2008) are considered as ‘an interindividual configuration where one person invites another to speak about a topic whilst effectively recognizing the right to inter-subjectivity, in other words, a right to an independent subjectivity’ (Matthey Reference Matthey2005: 5). We contacted people at the memory centre or by telephone, either directly with the person we wished to interview or through a family member. There were no refusals to participate in the study. All but two interviews were conducted at the interviewees’ residence, which is a protective setting for their identity (Hellström et al. Reference Hellström, Nolan, Nordenfelt and Ulla2007).

The interviews lasted from 30 minutes to three hours, and began with the following statement: ‘You have been diagnosed as having Alzheimer's disease. Can you tell me how you experience life with this disease?’ This made it possible for us to explore the two main lines of the interview guide. The first one concerns daily life with Alzheimer's disease. Several dimensions were explored: their previous or current occupational career and the effects of diagnosis on its advancement; family life and the nature of ties with relatives around and supporting people with Alzheimer's disease; social life and leisure. Lastly, an emphasis was placed on everyday life and daily tasks (driving, shopping, cleaning, etc.). More broadly, we tried to gather a wide-ranging discourse on social representations of the illness and ageing. The second line concerns the disease over time, trying to understand the history of the illness's development from their first problems up to the interview. We asked about the context of the appearance of their first difficulties, their decision to consult a doctor, the process leading to the diagnosis and the experience of receiving it. We also included questions on identity dynamics through these steps (claims to be ill or not, and in which contexts) and their potential evolution over time. The domains of the épreuve of ageing template were not directly addressed, as the idea was to collect discourses on these domains and the related existential issues through narratives on how people lived today and what the disease changed in their lives, but not through direct, leading questions.

Interviews were carefully transcribed then analysed in a two-phase process. In the first phase, each interview was analysed internally to identify its salient points and reconstruct its logic. This internal analysis was conducted both inductively and using a template for analysing the épreuve of ageing. Discourses corresponding to each domain of the épreuve of ageing were assembled in order to analyse them inductively, allowing the two researchers to discuss the interpretation. In the second phase, we conducted a transversal analysis in which we inserted discourse from all interviews into each of the domains on the épreuve of ageing template. In this phase of the analysis we paid particular attention to the variety of postures adopted, which we tried to reconstruct by building ideotypical typologies (Schnapper Reference Schnapper1999).

Findings

We now return to the épreuve of ageing's four domains to use them as a template for reading the interviews we conducted. This will show the extent to which this analytical template applies to our corpus and the ways in which it helps shed light on the épreuve of ageing with Alzheimer's disease. The results are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2. The épreuve of ageing with Alzheimer's disease

The domain of everyday activities, between déprise and holding on

In the first domain, we conclude that the déprise approach aptly applies to the people in our corpus. They told us how they came to give up activities they could no longer practice or that had been forbidden to them while trying to maintain others. This déprise is particularly present in certain kinds of activities.

It is first of all the case for reading, especially books, which becomes gradually more difficult as memory problems worsen. Thus Martine (age 76, former librarian) gave up reading books and contents herself with reading pamphlets of two or three pages, explaining, ‘not a whole book, because I don't know what I read at the beginning any more. That's how it is now’. Likewise, Michèle (66 years old, former businesswoman) buys herself little books of very short stories that allow her to continue ‘reading stuff’, even though it is increasingly difficult for her. Akso Paul (age 59, engineer) no longer reads novels, only technical journals.

Déprise next concerns the participants’ ability to go from place to place, whether on foot, by public transportation or by car. Indeed these trips become difficult when they lose their sense of orientation or become potentially dangerous behind the wheel. The practical and symbolic importance of this kind of activity has already been demonstrated (Balard Reference Balard2013; Caradec Reference Caradec2004), and it is a particularly good illustration of how déprise is built through interactions with family and health professionals, who may go so far as to force an afflicted person to stop driving. For instance, Lucie (76, former housecleaner) explains why she stopped taking the train:

It's not that I don't want to anymore, it's my head. I asked the doctor if I should go out or anything, if I wanted to go see my granddaughter, but you have to take the train to Paris, and you have to change trains to take another one. And he said no… so it's over, I can't go any more.

Lastly, there is a third area of activities that is especially diminished for the participants: communication. We will address this and give some illustrations in our discussion of the fourth domain, since it is also raises the question of the relationship of familiarity study participants have with the world.

Confirming the findings of previous work on déprise (Clément and Membrado Reference Clément, Membrado and Carbonnelle2010), the participants use these conversions to do what they can to continue activities that are especially important to them, and which they struggle to keep: running errands; cooking meals; reading (for Martine, cited earlier); writing books (Serge, a former professor, 66 years old, who is hesitant to give lectures because he no longer feels as sure of himself verbally); or taking care of one's animals as one has always done (Albert, a 55-year-old former labourer who lives in the country).

As in other work on déprise (Caradec Reference Caradec2007), we also observe the establishment of strategies such as taking notes, making lists or keeping a diary to compensate for memory problems. As we indicated earlier, these strategies depend both on participants’ previous trajectories and their available resources. For one thing, they depend on resources accumulated over their lifetimes. For instance, date calendars are familiar objects to some participants who used them in their professional lives or as a newly retired person, while others had never used one, such as Louis, an 80-year-old former farmer, or Roland, a former high-ranking civil servant of 64 whose secretary had always managed his schedule for him. But these strategies also come from the resources available in the present. Paul (59, engineer) was able to keep his job as a local civil servant by taking advantage of a specific illness leave programme and due to his director's particularly understanding attitude. Another example: Daniel's wife bought him (54, former architect) a dog that would subsequently play a central role in his life: it gives him company while his wife is at work and gives a rhythm to his days through regular walks that give him the chance to see the building superintendent and neighbours. We could add that these strategies may be more or less constrained: sometimes there is little flexibility left, as when an ill person is required to stop driving or, for those who are not yet retired, when the employer summarily puts an end to their professional activity.

Although the phenomenon of déprise is quite present in the interviews, it is also sometimes difficult to characterise because occasionally the interviewees’ speech seems ambivalent or even contradictory about how some of their practices have changed. The entangled and confused speech that runs throughout some interviews can be summed up by two formulations. The first is, ‘I don't do it anymore/I still do it’. Accordingly, Emile (former engineer, 76) – who we know no longer drives – explains that he now lets his wife drive because ‘she likes it a lot’ while assuring us that ‘that doesn't stop me from taking my car and going someplace by myself’. The second formula can be summed up as, ‘I don't do it anymore, but I still know how’. In fact, we could consider statements along these lines coherent if we account for two things: firstly, that they typically place different periods of their recent lifecourse into the same temporal frame, and secondly, that interviewees are emphasising skills that they think are preserved, even if they no longer use them, and try to present an identity little affected by the illness.

The domain of identity: self-presentation and definition

The identity issue seems to be essential for our interviewees, as their identities are threatened on two fronts. One is society's view of the illness (Kitwood Reference Kitwood1997; Langdon, Eagle and Warner Reference Langdon, Eagle and Warner2007). The participants in our study refuse to be thought of exclusively as ‘Alzheimer's sufferers’, knowing they are at constant risk of being discredited (Goffman Reference Goffman1963) and reduced to this single characteristic. The other is that their identity is threatened by the cognitive problems affecting them (Clare Reference Clare2003). The participants wonder how far these problems have advanced and ask themselves what they are still capable of doing and what they are worth, as in the case of Elisabeth, age 83, who doubts herself and wonders if she is still ‘up to’ her grandchildren. This double threat to identity opens two analytical paths towards self-presentation and self-definition.

We start by examining the first. Diagnosed people like those in our study wonder whether they have to tell people other than their closest family and friends that they have the illness (Beard Reference Beard2004). There are two general strategies. The first is trying to hide the illness to avoid being discredited. For example, Etienne (69, former engineer) refrains from mentioning his diagnosis to anyone outside his family circle for fear of being considered crazy: ‘I avoid talking about it, because people have such a negative connotation, um, of that thing, that they practically take you for, like, a nutter or talk to you like you're, y'know, a child, which I really want to avoid’. This strategy conforms to the observations of Langdon, Eagle and Warner (Reference Langdon, Eagle and Warner2007), who have stressed people's reticence to talk about their illness beyond their closest friends and family. In the opposite direction, the second strategy consists of stressing the diagnosis in order to justify certain strange behaviours and to try to limit other people's negative judgement. This is Michèle's (66, former businesswoman) strategy. She explains that ‘it's too obvious now … they [other people] really have to understand. Otherwise they might say, “but she's crazy!”’ Although this strategy seems to be the opposite of the previous one, the goal is similar since it, too, is about keeping her distance from the figure of a crazy person. But in the second case, it seems preferable to be taken for sick than for crazy. The transition from the first to the second of these strategies can moreover be observed when the former no longer seems tenable. This is the case for Alain (71, former doctor), who recounts how he came to tell his bridge partners of his illness:

Alain: So when I'm in public, like when playing bridge, well, I listen, but I don't, y'know, talk much, to not show too much that I have memory problems. Not long ago I used to always make like there was nothing, y'know. No, no, it hasn't been very long since I spoke up about it.

Interviewer: So actually, how did it get decided to talk about it?

Alain: Well, when I was forgetting the cards, then … Well, for that matter, maybe I did it like that. When I forgot cards, uh, I'd say ‘oh, that's right, I've got a…’ or ‘oh, I never remember anything!’, it began with remarks like that, y'know. How it happened exactly, that I couldn't say anymore (laughs).

Interviewer: Yes (laughing).

Alain: But that's exactly the problem. Now at least they know.

The second path for analysis opened by the domain of identity is that of self-definition. People with an illness find themselves faced with the question of knowing to what extent their identity is altered by their illness. Clare (Reference Clare2003) suggests that the answers are placed on a continuum between two extremes, running from ‘self-maintaining’ (when people normalise the situation and minimise the difficulties in maintaining continuity with their prior sense of self) to ‘self-adjusting’ (when they confront threats head on and try to integrate changes into the self). In our study, the participants’ discourses led us to distinguish between three postures, which could be called preserved identity, threatened identity and altered identity.

The discourse of preserved identity is that of interviewees who feel that their identity is little affected by the illness. They think that their problems are benign, that they are external to the self, and that they have few consequences on their lives. These minor problems do not change who they are, to the point that some of them even challenge the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Thus Louise (84, former preschool teacher) was shocked by the diagnosis because it is so far from the image she has of herself, as someone with the memory of an elephant. Today she lives as though the illness did not really concern her: ‘I still have the impression that I don't really have it … I don't know how to put it … I don't feel different! I still have my memories, I have everything’.

The second type is threatened identity. The illness has not yet touched the core of identity, but it is more present. What predominates in interviews, then, is worry about how it will develop and its future consequences, as well as the on-going fight to contain its progression through memorisation exercises or participating in therapeutic trials. We cite the example of Serge (65), a former professor specialised in the writer Verlaine, who presents himself as such and who explains that ‘so long as I'm still able to do intellectual work, I figure I am not entirely done for’. He still writes, especially as ‘it makes the neurons work’. But he fears the future because he knows that his problems will get worse and he has the impression he is in a race against time.

Lastly, the third type is altered identity. In this situation, the interviewees have the feeling that the illness has deeply affected who they are and they emphasise what they have lost (their previous capacities, activities they can no longer pursue, their autonomy), and consequently on the changing of their identity. Here we can cite the case of Michèle, a 66-year-old former businesswoman, who tells us what the illness has changed in her life. She cites everything she can no longer do: she can no longer write, she can barely read anymore, she has no more conversations. She stresses how much she has changed: ‘I was worth something, and then … and then … I had to decline’.

The domain of autonomy: between proclaimed autonomy and delegated autonomy

The basis of Alzheimer's disease is altered cognitive and decision-making functions, and it is thus commonly associated with the loss of decisional autonomy. At earlier stages of the illness, however, the situation seems more complex and varied. In our interviews, the question of autonomy leads to two positions: proclaimed autonomy and delegated autonomy.

First of all, as in research conducted on ‘normal’ ageing, many of our interviewees try to preserve their autonomy. Some do it with the support of their loved ones, like Paul (59, engineer) who regularly does memory exercises and whose wife endeavours to stimulate his mind so he does not let himself go. She explains that ‘when you focus on it, it comes back to you, it's not … It comes back, even if for a minute he goes “what are we doing this weekend?” and uh, I tell ’im “we already talked about it”. So, well, if he forces himself, he knows it. So I also try to not always repeat’. Loved ones, then, have to arrive at what we could call the ‘right amount’ of support, as Alain (71, former doctor) mentions in speaking of his wife:

Alain: It's her role that's the hard one, actually, because, knowing when she should intervene, um … So sometimes she intervenes too quickly, when I'd actually understood.

Interviewer: It's maybe in anticipation of your problems?

Alain: Yes, that's it, that's what's not easy for her to judge … there's a learning curve for accepting the gaps and for the others to adapt, and for us to adapt, too.

This is a good example of what Collopy (Reference Collopy1988: 16) called ‘positive autonomy’, in opposition to a ‘negative’ view of autonomy that asks for non-interference. Spouses struggle together to enhance the ill person's autonomy. Finding the right balance is an arduous task, however. Serge (65, former professor) captured it well when he explained that he gets irritated ‘when my wife repeats what she's already told me ten times … because it's kind of about pride, y'know – I'm not as far as you think!’ Participants’ autonomy may also be maintained by the balance of power with friends and family, holding their excessive solicitude at bay in order to limit their tendency to make decisions for them and demonstrate that they can still take care of themselves. Lucie (76, former housecleaner) decided to renovate her kitchen without first discussing it with her children, and although she lets people take her shopping, once she is in the store she wants to do it alone and choose her purchases herself. Protecting one's autonomy from loved ones nevertheless presupposes great vigilance, because it is important to not make a slip that might worry them and lead them to intervene more: Lucie is always very careful to check several times that she has turned off the gas.

Inversely, there are also situations where ill people seem to have renounced their autonomy and left all everyday life decisions to a family member, usually a spouse. In such cases autonomy is delegated to loved ones with whom they voluntarily build ties of dependence. This kind of situation aligns with analyses that, in opposition to a long intellectual tradition claiming the contrary, emphasise that autonomy does not mean independence. It ‘cannot be viewed as separate from the relationships within which individuals are embedded’ (Hillcoat-Nallétamby Reference Hillcoat-Nallétamby2014: 420) and might be compatible with a situation of care and solicitude (Agich Reference Agich2003; Holstein, Parks and Waymack Reference Holstein, Parks and Waymack2010; Rigaux Reference Rigaux2011). In this regard, delegated autonomy should be recognised as a valid form of autonomy (Collopy Reference Collopy1988). In some cases in our corpus, however, this delegation seems particularly radical, because it is not limited to some areas but touches all aspects of life. It is important to point out that such delegation of autonomy may be accompanied by a certain sense of wellbeing or even an affirmation of the pleasure of being alive. Emile (76, former engineer), who now relies on his wife, sums up how he experiences his current situation by saying, ‘I think I'm happy the way I am’. Charles (82, former accountant) stresses how indispensible his wife's presence is for him, as much emotionally as materially. She and his daughter are the only reasons he has left to live. He is no longer interested in anything, lets his wife make all the decisions and feels happy that way because, he explains, he thinks that ‘I've done my share’. This wellbeing expressed by the person delegating his or her autonomy may or may not be shared by his or her spouse (Caradec Reference Caradec2009). Charles’ wife feels rather good about the situation because her top priority is keeping her husband by her side, so she prefers seeing him ill to losing him forever. But Emile's wife emphasises her exhaustion from having to manage everything herself without getting the recognition she needs, and expresses her pain in seeing her husband change and become something other than what he was.

The domain of relationship to the world: the communication question

The domain of relationship to the world, which is associated with the feeling of foreignness that tends to develop with age, brings us to an essential question concerning people with Alzheimer's disease: communication with others. Indeed, the issue of maintaining a certain familiarity with the world revolves around communication for people with Alzheimer's because the illness tends to complicate both of the fundamental conditions for communication – possessing communication skills (knowing how to listen, remember and express oneself) and having a minimal social life (which presupposes having other people around and being listened to).

The illness affects these two conditions variably, leading us to distinguish three pathways where communication ends up being weakened. In the first case, the difficulties mainly arise from reduced communicational skills when the social setting is favourable. For example, Michèle is still well tolerated by her husband and friends, but she participates less and less in discussions because, as she explains, ‘there are conversations that last … I don't know how long, with everyone and all that. And I don't say anything. I can't because I don't understand anything. I can't say a word’. In the second case, the difficulty lies less in the loss of communicational skills than in the weakness of social relations. Elise (66, former teacher) thus painfully explains that her family and friends have grown distant ‘since she's in Alzheimer's’ and that she lives in a retirement home, a place where ‘people don't talk much’, ‘that is empty’, where ‘nothing happens’. Lastly, in the third case, communicational skills are preserved and there is family present, but relations are tense because the ill person feels like what he or she has to say is no longer legitimate. This kind of conflict-ridden setting is what causes people to close in on themselves. Our interview with Lucie (76, former housecleaner) thus illustrates a communicational situation marked by great tension that obliges her to evaluate constantly whether she can risk speaking up: ‘I pay attention. When I want to say something, sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn't. Well then, I say, I get it, next time I won't say anything, period, and that's that’. Faced with these difficulties, people with Alzheimer's disease implement a variety of strategies that can be grouped into two clusters: looking for palliative solutions to maintain communication and abandoning customary ways of communicating with others.

The first strategy consists of trying to maintain communication by using a variety of resources to make it possible to pursue conversations and ‘save face’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1967). These resources may be material objects, which play the role of memory supports and facilitate conversation. Over the course of our interviews, for example, one interviewee took recourse to a digital tablet with images that helped back up what he was saying, and another went to get a product label to be able to give its name. It may also be a matter of mobilising what Goffman called ‘safe supplies’ (Goffman Reference Goffman1953: 206–16), by developing clichéd comments on the passage of time or urging the interviewer on with expressions like ‘onward! next!’ in order to hide his or her inability to continue with what he or she had been saying, to give a couple examples. Still other resources come from the past, interviewees using that which is the most accessible to them in their memories. Louis (80, former farmer) thus enjoys talking about the past with his sister, distancing himself from the memory problems that are particularly associated with recent events: ‘We talk about the past, we understand the past, we remember it (laughs). But the present, there, these machines, these new things that kind of lose us, we didn't learn soon enough’. Lastly, it is also possible to fall back on humour to manage a disphoric interaction situation, disrupted by strange behaviour or speech (Goffman Reference Goffman1953: 259–72). A dash of humour thus allows someone to save face and put the conversation back on course while shifting the awkwardness to other participants. This is what Martine (76, retired librarian) tells us: ‘I don't like it when people make unpleasant comments to me … So, um, in cases like that I laugh and say “well sure, that's how it is, I'm the village idiot!” Then people are a little … bothered, of course. They are uncomfortable’.

The second strategy consists of abandoning the usual ways of communicating with others. Some speak little, or even withdraw from conversations they can no longer follow (like Michèle, cited earlier), thus making it necessary to find less-demanding or especially tolerant conversational partners. So it is that Daniel (54, former architect) sometimes slips away from the adult table during large family meals to take refuge with the children to shelter himself from being present for conversations making him feel like a stranger. Also Philippe's wife remarks on her husband's painting teacher's skill communicating with him (57, former labourer) when even she has the feeling she cannot get ‘through his bubble’:

She has a way of talking with him. Like, he's not stressed, I'll say. Sometimes he makes mistakes in his pictures, I am almost watching what he's doing because I'm afraid that he doesn't know, while the teacher is super cool with him and always tells him in a funny way, so he laughs, even if he forgot … He takes it well, basically, something that sometimes, with us, he doesn't take so well.

It could also be favouring interactions with animals, which prove to be more readily accessible than people and do not challenge failing relational skills. The relationship between Daniel and the dog his wife gave him is revealing on this point. The dog, which as we saw earlier has a major role in keeping him occupied in daily life, is also a precious resource for maintaining a degree of communication and a space for speaking, since Daniel has some problems in this regard. Throughout the interview he struggles to find words and organise his thoughts, but he seems much more self-confident when he interacts with his dog. The interview was constantly interrupted by the orders he gave his dog: ‘What are you doing?’, ‘To the rug!’, ‘Sit and stay!’, ‘We don't run around in circles by the television!’ The dog seems to be his favoured interlocutor, much more than the interviewer – ‘a companion’, he says, attentive and possible to communicate with: ‘you have the impression that he understands … I talk to him, he tries to talk, too’. We should also point out that such undemanding partners in interaction also include technological devices like television or radio, which speak without expecting a response.

Discussion and conclusion

This paper applied the concept of the épreuve of ageing to people at a mild or moderate stage of Alzheimer's disease. The concept of épreuve has the benefit of articulating the macro- and micro-sociological levels. While épreuves are socially produced and vary from one country to the next, the concept is an invitation to study how people face them. It then leads to the emphasis of key existential issues for people in their home society.

When applied to the field of ageing in French sociology, this approach leads to the elaboration of a template of the épreuve of ageing, which is an attempt to think ageing otherwise than through the lens of decline or successful ageing. The template differentiates four domains (activities, identity, autonomy and relationship to the world) and highlights four associated existential issues: maintaining connections with the world, social value, autonomy and familiar spaces in the world. It was developed based on research with older people, most of them over the age of 80 and thus in ‘the fourth age’ (Lalive d’Epinay and Cavalli Reference Lalive d'Epinay and Cavalli2013; Lloyd et al. Reference Lloyd, Calnan, Cameron, Seymour and Smith2014). These studies were based on semi-structured interviews with people without cognitive problems, although we cannot exclude the possibility that some may have slipped into the sample. This analytical template is thus valid in the field of so-called ‘normal’ ageing, since it excluded people experiencing what might be referred to as ‘pathological’ ageing. Hence, this raises the question of whether it might be applicable to people at a mild or moderate stage of Alzheimer's disease, thus shedding light on the épreuve of ageing with the disease.

The domain of activities shows few differences from findings of previous studies on ‘normal’ ageing. Some areas of activity are more affected, especially reading, getting around and communication. As for the issue of identity, the situation seems worse because the illness presents a double challenge: managing how one presents oneself to others and the risk of being stigmatised, and reacting to the question of how much the illness is affecting one's identity (is it preserved, threatened or altered?) In the domain of autonomy, our study supports previous findings emphasising that ageing people struggle to maintain their autonomy, but it also fleshes out the existence of a situation that is only roughly outlined in work on ‘normal’ ageing: autonomy delegated to a loved one, in a relationship characterised by heavy dependence. Lastly, the domain of the relationship to the world reveals a major aspect of the experience of ageing with Alzheimer's disease – weakening communication – which can lead people with Alzheimer's disease to limit challenging interactional situations and to take refuge in their inner worlds. They thus construct a form of strangeness with the world that is more radical than what is observed in other research on ageing.

The research presented in this paper demonstrates that ageing with Alzheimer's disease does have its specificities. For all that, interviews with people at a mild or moderate stage of the illness do have points in common with interviews in studies of ‘normal’ ageing. We have seen that the épreuve-of-ageing model described how ageing people confront a range of challenges that are more frequent with age: health problems, functional limitations, the deaths of their peers, their loved ones’ worry, ageism. In fact, Alzheimer's disease appears as one of these challenges and, at least at the outset of the disease, people affected by it deal with it as other ageing people confront their problems: by using the resources at their disposal and implementing strategies to adapt to it and by maintaining their sense of self through perseverance (Lloyd et al. 2104). From this perspective, the experience of ageing in earlier stages of Alzheimer's disease is not a radically different form of the épreuve of ageing. Instead it exacerbates issues – at least until the moment when communication becomes difficult and the tools of phenomenological sociology become powerless for analysing what is happening.

This research also more generally urges us to think about the role of age in the ageing process. In the model of the épreuve of ageing that we presented here, age itself is not put into question, but rather the fact of being confronted with difficulties that are increasingly likely to appear with advancing age. From this point of view, our corpus contains several ‘young’ sufferers who were diagnosed before the age of 60. They could be thought of as experiencing a sort of early ageing, as they face problems that usually appear later in life. The results are therefore an invitation to enlarge the study of ageing by comparing people at different life stages who are confronted by the same challenges (Chamahian and Lefrançois Reference Chamahian and Lefrançois2012).

The analytical template has proved to be valuable for analysing the interviews in our corpus. The four retained domains and the four associated issues were a useful framework for describing what comprises ageing with Alzheimer's disease in a society where there is a dark imaginary about this disease which is viewed as a stigma. This template also allowed us to identify the diversity of experiences of people who, from a medical point of view, present a similar profile. The épreuve of ageing template therefore looks promising for analysing and comparing other situations of ageing, for example the ageing of people with other diseases, such as cancer, or the ageing of people with disabilities, or at the opposite the ageing of people reaching 90 or 100 with no disease, and for asking what is specific and what is common in these experiences. As the challenges are not the same, we can assume that déprise takes different forms and that identity, autonomy and relations to the world are not affected in the same way, but that there is a common endeavour to cling to what is important in life and to preserve a sense of self. The template is also promising for analysing ageing in different geographical areas and in different relational contexts, and for asking how material and relational environment impact the different dimensions of the épreuve. In particular, the épreuve of ageing could be studied more specifically for people who age with no close family, since relationships with close family appear so important. More broadly, the concept of épreuve could be applied to some specific moments in the ageing process, such as retirement, with the possibility of a comparison between different countries, since it allows one to connect how people live the transition with both their social resources and the conditions of retirement in their country (age of retirement, amount of pension income, incentive to continue working).

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Professor Florence Pasquier, professor of neurology and head of the Memory Consultation Centre at the Regional University Hospital Centre in Lille, France and to the whole staff of the Memory Consultation Centre for making possible this research by facilitating access to people with Alzheimer's disease. This study was funded by the Fondation de Coopération Scientifique pour la Recherche sur la Maladie d'Alzheimer et les Maladies Apparentées (Foundation for Scientific Co-operation for Research on Alzheimer's Disease and Related Illnesses).