All psychiatric trainees who wish to take the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ examinations must attend an MRCPsych course. The establishment of the Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board (PMETB) led to changes in postgraduate psychiatric training, both in the curriculum and in the way that training is assessed, and MRCPsych courses have had to adapt in order to reflect these changes (Reference BhugraBhugra 2007). However, the manner in which they have done so has not been set down by the College. This article will review the history of MRCPsych courses and how they have evolved.

In the UK, MRCPsych courses are usually provided locally by trusts or university departments. There are a number of websites designed to complement these local courses, including www.trickcyclists.co.uk, www.superego-cafe.com and www.vjpsych.ie. The revision courses that are designed for intensive cramming before the College examinations (sometimes also referred to as MRCPsych courses) fall outside the scope of this article. A more detailed account describing how changes have been implemented on the Birmingham MRCPsych course (Reference Vassilas, Haeney and BrownVassilas 2008) will be given. The different delivery methods utilised both locally and further afield will be described, and the theoretical background that lies behind these different approaches will be explained.

Background and historical development

The Basic Specialist Training Handbook of the Royal College of Psychiatrists (2003) states that:

All trainees must attend a recognised MRCPsych course comprising a systematic course of lectures and/or seminars covering basic sciences and clinical subjects relating to basic specialist training and the published MRCPsych curriculum.

Although in the past the College has held conferences for MRCPsych course organisers in the UK and Ireland to discuss the content and objectives of their courses (Reference CoxCox 1996), there is currently little advice offered on how to run a course other than the above statement.

Courses have evolved in different ways across the UK. In Southampton, for example, a day-release course was set up in 1966 – this was designed to help trainees pass the Diploma in Psychological Medicine of the College's forerunner, the Royal Medico-Psychological Association. This course continued to develop after the Association became the Royal College of Psychiatrists in 1971, with the subsequent introduction of the MRCPsych examination (Reference NottNott 1990).

There are now 30 different MRCPsych courses available to psychiatric trainees in the UK and they fall into two categories: one is a specific MRCPsych course, and the other is a Masters degree course, which offers preparation for the MRCPsych examinations as part of the course. Proponents of Masters courses argue that close links with a university ensure that teaching is of a high quality and that the academic aspects of psychiatry are promoted (Reference Sullivan and JonesSullivan 1997). On the other hand, such courses are often costly in terms of both finance and time, and may not focus sufficiently on the essential task of preparing trainees for the MRCPsych examinations. There has been a decline in the number of Masters courses from 11 in 1995 (Reference Shoebridge and McCartneyShoebridge 1995) to 8 currently.

The PMETB was established in 2003 and took overarching responsibility for setting the standards for training in postgraduate medical education in the UK in 2005. It became ‘the sole competent authority responsible for the approval of training such as posts and programmes that directly contribute to the award of a CCT [Certificate of Completion of Training]’ (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board 2008). To carry out this function, PMETB worked closely with the medical Royal Colleges and with the UK Deaneries. The medical Royal Colleges are responsible for developing curricula and assessment processes, which the Deaneries and local education providers deliver (Postgraduate Medical Education and Training Board 2008). In psychiatry, this resulted in the introduction of new examinations and the development of workplace-based assessments. These changes have coincided with the Modernising Medical Careers agenda and the European Working Time Directive (EWTD, fully implemented in August 2009). Both of these changes have meant that there is less time available for training in psychiatry. The limited time available for education therefore needs to be used more efficiently and this is bound to have an impact on how MRCPsych courses develop.

Responsibility for regulating all stages of medical education in the UK now lies with the General Medical Council (GMC), after PMETB merged with the GMC in April 2010.

Theoretical principles

When describing how to set up an educational programme, it is useful to consider the theoretical background. The ideas described below are all important within medical education and have been supported by findings in the field of cognitive psychology (Reference Regehr and NormanRegehr 1996).

Andragogy

The first important notion to consider is that of andragogy. Alexander Kapp, a German secondary school teacher, first introduced the term in 1833 to describe the learning process in adults. Andragogy describes learning strategies that are focused on adults, for whom learning is self-directed and teachers act as facilitators rather than simply delivering content. The term was popularised in North America by Reference KnowlesKnowles (1973), who distinguished andragogy (from the Greek ‘man-guiding/leading’) from the commonly used pedagogy (from the Greek ‘child-guiding/ leading’). He initially described four assumptions about adult learning, which were later expanded to five (Knowles 1984). These in turn form the basis of seven principles of andragogy that Reference KaufmanKaufman (2003) has usefully summarised (Box 1).

BOX 1 The seven principles of andragogy

-

1 Establish an effective learning climate, where learners feel safe and comfortable expressing themselves

-

2 Involve learners in mutual planning of relevant methods and curricular content

-

3 Involve learners in diagnosing their own needs – this will help to trigger internal motivation

-

4 Encourage learners to formulate their own learning objectives – this gives them more control of their learning

-

5 Encourage learners to identify resources and devise strategies for using the resources to achieve their objectives

-

6 Support learners in carrying out their learning plans

-

7 Involve learners in evaluating their own learning – this can develop their skills of critical reflection

Deep and surface learning

Two models of learning are commonly used to describe how students learn. The first model, by Reference Newble and EntwistleNewble & Entwistle (1986), suggests that students have different approaches to learning and that broadly these can be divided into surface, deep and strategic learning. Strategic learning is motivated by a desire to be successful and leads to patchy and variable understanding. Surface learning is motivated by fear of failure and a desire to complete a course, with students tending to rely on learning ‘by rote’ and focusing on particular tasks. Deep learning is characterised by learners having an interest in the subject matter and considering it to be relevant.

Deep learning is more likely to be associated with better-quality learning outcomes (The Council for National Academic Awards 1992). Reference GibbsGibbs (1992) suggested three ways to help learners adopt a deep approach:

-

• motivational context – adults learn better when what they need to know enables them to carry out tasks that matter to them, so the content should reflect their day-to-day working experiences;

-

• learner activity – students need to be active rather than passive;

-

• interaction with others – this is an important way that learners can grasp new ideas.

The way the teaching is delivered can be structured to encourage deep learning using these principles. Some of the methods that may be used to achieve this are described below.

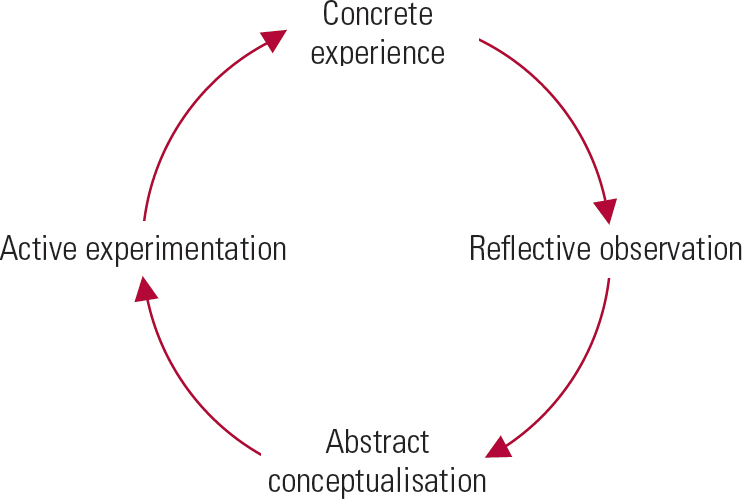

The second theory to consider is that of Reference KolbKolb (1984). His experiential learning theory builds on the work of three earlier educationalists that were important figures in developing educational theory: John Dewey, Kurt Lewin and Jean Piaget. Kolb defined learning as ‘the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of experience’ and described four approaches:

-

• concrete experience (experiential learning) – this is the starting point for the learning process;

-

• abstract conceptualisation – development of analytic strategies and theories;

-

• active experimentation – learning through action and risk-taking;

-

• reflective observation – viewing problems from multiple perspectives before deciding how to proceed.

Figure 1 illustrates Kolb's cycle and shows how the four approaches are linked together.

FIG 1 Kolb's educational cycle. (After Reference KolbKolb 1984, with permission.)

Reflective practice

Reflection is an important part of the learning process for adult learners. Reference BouchBouch (2003) has written that, as psychiatrists, ‘reflecting on our experiences at work is … of central importance to learning’. The concept was originally developed by Reference SchönSchön (1987) who described a theory of professionalism and reflective practice. Schön defined reflection as an active process which does not occur spontaneously; in particular, he describes ‘reflection-on-action’, which is a retrospective feeling about an experience. By reflecting on experience in a structured way, learning can take place that will influence future practice. This observation and also reflection on experience were considered by Kolb as important parts of the learning cycle (Reference Kolb, Fry and CooperKolb 1975).

Reference KaufmanKaufman (2003) summed up the above theories in the following way:

learners must have the opportunity to develop and practise skills that directly improve self directed learning. These skills include asking questions, critically appraising new information, identifying their own knowledge and skill gaps, and reflecting critically on their learning process and outcomes.

The educational climate

The surroundings in which learning takes place is referred to as the educational climate or environment. There is a proven connection between the environment and the outcomes of students’ achievements, satisfaction and success. Reference Chambers and WallChambers & Wall (2000) divide the educational climate into three parts:

-

1 the physical environment: comfort, food, room temperature and ventilation;

-

1 the emotional climate: whether the learners feel that it is safe to speak, receive positive reinforcement, etc.;

-

1 the intellectual climate: whether the teaching is evidence-based, up to date and follows best practice.

To maximise learning, any programme of teaching must address these areas.

Methods of teaching

Various MRCPsych courses across the UK and Ireland have developed different ways of delivering teaching. By way of illustration, we focus on one course being run in Birmingham.

On this course, the teaching has been traditionally delivered in a lecture format. Small-group teaching was identified as one means of increasing inter-activity within the teaching sessions. Discussions took place as to whether the entire course should be delivered in this format. This would have required one or two facilitators for three or four groups of trainees in each of the 3 years of the revised MRCPsych course. It was decided not to deliver the whole course in a small-group format because of resource limitations and also because trainees wanted to retain lectures. A mixture of teaching methods was used instead. The course has also moved from a loose ‘ragbag’ of lectures towards a modular format in order to increase coherence and compatibility with the MRCPsych curriculum.

Small-group teaching – theory and practice

Small-group teaching takes place when learners work together in groups of about 12 or fewer. Three characteristics are described: all learners actively participate; the group has an explicitly learning-defined task; and the experience of the learners encourages reflective learning to take place (Reference CrosbyCrosby 1996). It is an effective method of teaching (Reference Springer, Stanne and DonovanSpringer 1997) and is a way of enabling deep learning to take place.

There can be difficulties with this approach; for example, Reference JaquesJaques (2003) describes learners not preparing for lessons, learners not talking to one another or teachers talking too much. He then describes a variety of strategies for dealing with these, emphasising the need for the group facilitator to structure the group effectively while not intervening excessively. Jaques suggests that the facilitator should ensure that all group members understand what is expected of them both during group meetings and in terms of preparation for teaching sessions. Group members can be encouraged to speak by the facilitator consciously not repeating or reformulating a question or not speaking unless there are clear reasons to do so. Other strategies include the facilitator deliberately looking at all group members while they or another group member is speaking.

At least one MRCPsych course (in Keele) runs entirely using small-group work. On the Birmingham MRCPsych course, small-group teaching has been implemented for the Year 1 trainees (n= 40) and the overall number of lectures reduced, with lecturers encouraged to introduce interactive methods into their teaching where possible (see below). Year-1 trainees have lectures for 3 h every week for 3 weeks. Every fourth week they are split into small groups of 8–12.

To achieve the successful running of the small-group teaching, facilitators were trained and a handbook developed.

Training facilitators

Because the small-group teaching was being introduced for the first time, considerable effort was put into supporting and training group facilitators. It is likely that in subsequent years less input will be necessary. Facilitators were recruited from among higher trainees with an interest in education and from the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ tutors. Tutors and trainees paired up to run five small groups. A total of five training sessions were organised over a year for facilitators.

During the introductory session, the concept of the course was explained and ideas were shared about useful content for the course and modes of delivery. The use of feedback techniques was identified as an area that the facilitators wished to develop further and so a subsequent session was organised where feedback skills could be enhanced. Pendleton's rules (Reference Pendleton, Schofield and TatePendleton 1984) and SET–GO techniques (Reference Silverman, Draper and KurtzSilverman 1997) were the two methods of giving feedback that were discussed in the session (Box 2).Footnote †

BOX 2 Strategies for giving feedback on communication skills

|

Feedback using the SET–GO method

Learner/interviewer to base feedback on their recorded interview by stating:

|

Pendleton's rules

The following two key questions are asked and the answers are provided sequentially by the group:

|

At subsequent meetings the exact content of the teaching sessions was explained and discussions took place as to the best way to organise them. During the year, these meetings were used to talk about how the teaching sessions had gone and facilitators were encouraged to discuss their concerns and suggest solutions to any problems that had been identified. This training was designed to encourage the development of an appropriate educational climate.

Production of a small-group handbook

A handbook was prepared outlining the content of each small-group teaching session, containing copies of journal articles and references. The handbook provided facilitators and trainees with a reminder of which lectures they had already attended. A brief outline of the content of these lectures was included to reinforce the idea that the small-group teaching was part of the same course as the lectures. Activities during the teaching sessions were designed to appeal to a variety of different learning styles, offering trainees the opportunity to build on information that they had already gleaned in the lecture sessions. A timetable was designed for each session which facilitators were asked to follow. Sufficient detail was given to ensure that the session was completely filled, but flexibility was allowed so that individual groups could explore areas that they felt were important.

Lectures – theory and practice

The lecture or large-group teaching remains the most common teaching method. It can be an efficient way of imparting and explaining large amounts of information (Reference Brown and ManogueBrown 2001). As described earlier, the first year of the Birmingham MRCPsych course now has a substantial small-group teaching element, but the remaining years (Years 2 and 3) have remained largely lecture-based.

It is important that lectures are planned; they should be relevant, clear, interesting, easy to follow and encourage the learners to think. Reference Brown and ManogueBrown (2001) suggests a variety of ways to encourage learners’ interest by making lectures more interactive. Ways of doing this on an MRCPsych course include using video clips, setting multiple-choice questions, asking learners to discuss a case or topic in small groups for a brief period of time and asking students to consider the advantages and disadvantages of a theory or treatment. Additional methods of encouraging interactivity include critical reviews, multidisciplinary sessions and service user and carer teaching sessions; these are described in more detail below.

Small-group teaching and lectures should be seen as complementary. With smaller numbers of learners there is likely to be a less of a distinction between the two styles of teaching. Box 3 compares some of the features of each.

BOX 3 Small-group teaching and lectures compared

Small-group teaching

-

• Interactive audience

-

• Promotes synthesis of information

-

• Promotes deep learning

-

• Problem-solving

Lectures

-

• Passive audience

-

• Promotes delivery of large volumes of information

-

• In keeping with surface learning

-

• Covers key areas necessary to enable group discussion

Organisational structure

Any educational course needs an administrative structure within which it operates. Because of the variation in how courses are run across the UK, the administrative structures will themselves vary. In the West Midlands, postgraduate psychiatric education is the responsibility of the West Midlands School of Psychiatry and the Chair of the Birmingham MRCPsych Course Board is appointed by the School. The Course Board, headed by the Chair, is responsible for organising the MRCPsych course. Box 4 lists the members of the Board as an example of how a course can be operated.

BOX 4 Membership of an MRCPsych Course Board

-

• Chair of the Course Board

-

• Honorary university lecturers (higher psychiatric trainees appointed jointly by the MRCPsych Course Board, each responsible for a year of the course)

-

• Postgraduate medical education manager

-

• Two carer and service user representatives from the service users’ and carers’ group

-

• The four rotational tutors whose trainees attend the course

-

• A university representative

-

• Trainee representatives for each year

Overview of an MRCPsych course teaching programme

On the Birmingham MRCPsych course, 110 students are enrolled from across the region. As in other MRCPsych courses, students are a mixture of postgraduate trainees (in their first 3 years of postgraduate psychiatric training) and specialty doctors (non-training grades). A model of a 3-year programme has been adopted whereby trainees are split into three groups, dependent on which year of training they are in. Previously, there were two courses, one for the old Part I of the MRCPsych examinations, which ran over two semesters, and another for the old Part II examination, which ran over three semesters. All trainees attend for half a day per week for 31 weeks of the year. Each year is focused towards sitting an exam at the end of the year. The content of the course is matched to the MRCPsych examination curriculum for each examination paper. Modules provide blocks of teaching lasting between 4 and 6 weeks. During these blocks, an entire segment of the curriculum is covered. One trainer has responsibility for a discrete module. At the end of each block, multiple-choice questions are set to assess how much the trainees have learnt from the course and also to enable trainees to identify areas where further study is needed.

There is wide variation in MRCPsych course size and geography and this will affect the way a course is run. Having three discrete year groups may not be possible or desirable for smaller courses. Similarly, if trainees need to travel long distances to get to a course, it might be simpler for them to attend a full day on alternate weeks rather than half a day each week.

Elements of the programme

Problem-based learning

Small-group teaching allows the introduction of a form of problem-based learning. In problem-based learning, trainees use ‘triggers’ from the problem case or scenario, which they are given in their group sessions, to define their own learning objectives. They then carry out independent, self-directed study before returning to the group to discuss and refine their acquired knowledge. Thus, problem-based learning is not about problem-solving per se. Rather, it uses appropriate problems to develop knowledge and understanding (Reference WoodWood 2003). Detailed case vignettes may be provided to promote questions and discussion. Trainees are encouraged to choose key areas to explore in further detail. This allows them to identify areas in which they already have adequate knowledge and areas where they may have gaps in their understanding. Trainees can then tailor their learning to their own needs and those of the group.

Communication skills training

Communication skills can be taught well in small groups. Using video recordings of interviews to provide feedback is a powerful method for developing communication skills (Reference Vassilas and HoVassilas 2000). Two half-days are set aside during Year 1, a role-player is recruited and the trainees given a specific task (e.g. explanation of treatment options in bipolar affective disorder or exploration of depressed mood). Each session is recorded on a DVD and lasts about 7 min. The video clips are then reviewed by a group of four service users who provide written feedback – the service users are instructed on how to use Pendleton's rules (Reference Pendleton, Schofield and TatePendleton 1984) and give feedback in this format. This feedback is presented to the trainee in a subsequent small-group session when their interview is shown to the group. During this session the video clips are reviewed by facilitators and trainees who are encouraged to use the SET–GO method of feedback (Reference Silverman, Draper and KurtzSilverman 1997). This process allows the trainees to reflect actively on their communication skills and to think about strategies for improving their skills.

Using film to teach

Using commercial films that portray mental illness is a potentially useful aid to teaching psychiatry and is attracting more interest (Reference Fritz and PoeFritz 1979; Reference ByrneByrne 2009). As an illustration, on the Birmingham MRCPsych course, a selection of film clips was identified to fit in with the teaching programme. Each film clip lasted about 3–5 minutes and consisted of a series of scenes from a particular movie. These were then discussed in the small-group teaching sessions. Clips from commercial films included Girl, Interrupted (1999, James Mangold), A Clockwork Orange (1971, Stanley Kubrick) and Mr Jones (1993, Mike Figgis). Clips depicting Piaget's developmental stages, Ainsworth's ‘strange situation’ and the film 1 in 4 from the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ Changing Minds campaign were also shown.

The above are just a few examples of films that can be used: a more extensive list of films that could be used for teaching psychiatry has been produced by Reference BhugraBhugra (2003). The films help to facilitate discussion regarding the social aspects of psychiatry within a small-group setting; the fictional depictions in particular act as a stimulus to debate.

Evidence-based medicine journal reviews

Various styles of teaching critical appraisal to trainees have been described (Reference SwiftSwift 2004). One approach that has been successful locally involves a combination of small- and large-group sessions. Two trainees are asked to review a paper before the teaching session and present a summary of it to the other trainees in a large-group setting. The trainees are then asked to split into small groups of five or six to answer specific questions relating to the paper set by the two lead trainees. Examples of questions for a randomised controlled trial might be ‘How applicable is this to the patients I see?’ and ‘How did the authors deal with people who dropped out from the study?’ Each group has copies of the journal article and prepares answers to the questions. After 20 min, the trainees reconvene as a large group and feed back their answers. These sessions are led by the two trainees who will have prepared answers beforehand, although a facilitator (usually one of the higher trainees) is present in case problems arise.

Journal review sessions give trainees the opportunity to develop their own teaching skills, while providing an informal environment for the other trainees to build on their group working skills, exchange ideas, and express their knowledge about critical appraisal while learning from others within the group.

Multidisciplinary learning

Increasingly, multidisciplinary team work is seen as necessary for the effective and efficient delivery of healthcare (Department of Health 1997). For multidisciplinary teams to work productively together, they must also learn together, both in the sense of learning generic skills and in terms of gaining insight into different professionals’ ways of practice (Standing Committee on Postgraduate Medical and Dental Education 1999).

In Birmingham, there is already some linked teaching between psychiatrists and clinical psychologists. Discussions are taking place with the University of Birmingham to see whether more joint learning with social work, nursing and clinical psychology students can take place. The development of a modular course lends itself to this type of collaborative learning so, for example, it is proposed that nurses training in old age psychiatry will join the old age psychiatry module of the Year 2 course. The challenge is to ensure that multidisciplinary learning takes place and not just multidisciplinary teaching (Reference CoxCox 1996).

User and carer involvement

In June 2005, the Royal College of Psychiatrists made it mandatory for psychiatric trainees to receive training directly from service users and carers (Reference Fadden, Shooter and HolsgroveFadden 2005). The vision of the College was that service users and carers should be involved in the planning, delivery and evaluation of psychiatric training as well as the assessment of psychiatric trainees. In Birmingham, a service users’ and carers’ group, designed specifically to provide input to the MRCPsych course, was set up in 2007 (Reference Haeney, Moholkar and TaylorHaeney 2007). Members of this group have a place on the MRCPsych Course Board (Box 4). As a result, new approaches to achieve service user and carer involvement, such as that seen with the communication skills assessment for Year 1, have developed. In addition, service users and carers run seminars and teach about areas that they have identified as being important to them and to the training of psychiatrists.

In Year 2, there is a workshop session where service users and carers give short presentations on confidentiality and the experience of detention under the Mental Health Act. The group is then divided into smaller groups facilitated by service users and carers to discuss a number of clinical scenarios. In Year 3, service users and carers lead large-group sessions on four of the modules, including learning (intellectual) disability and old age psychiatry.

This level of involvement represents a move away from the old style of teaching whereby service users were given a subject to talk about or were told that it did not matter what they taught as long as they taught something. It is consistent with the aims of the College's Fair Deal campaign to make service user and carer involvement meaningful and not tokenistic (Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008).

e-Learning

This is an area in which there is huge scope for expansion. The College has already developed e-Learning for its members (Reference HareHare 2009). It is relatively easy for MRCPsych courses to have their own websites, which at a basic level can have lecture programmes and copies of lecture presentations posted on them. The Centre for Excellence in Interdisciplinary Mental Health (with whom some of the work with carers is organised) has a website with a large amount of video material available (www.ceimh.bham.ac.uk). Potential areas for development include learner discussion groups and the posting of more learning materials onto the website. The possibilities are far-reaching, with the creation of interactive forums and even online lectures negating the necessity for trainees to travel long distances to attend lectures. Such innovations will require the back up and cooperation of an information technology (IT) department with both resources and commitment.

Putting it all together

Resources

In addition to the handbook for facilitators and trainees in the Year 1 small-group sessions, handbooks have been developed for the large-group teaching programmes in Years 1–3. These contain a copy of teaching programmes and an explanation of the course as well as key references to enable the trainees to find further information for themselves. The handbooks indicate what it is that the student should learn and advise how they might achieve that learning.

As noted above, the physical environment in which learning takes place is important and having dedicated teaching facilities makes a significant difference. The majority of the teaching takes place in the main postgraduate teaching centre of our trust. In addition, three of the five Year 1 small-group sessions are run at local teaching centres in the West Midlands region. Joint sessions with service users and carers take place in the University of Birmingham at the Centre for Excellence in Interdisciplinary Mental Health. Administrative support is vital and spans a huge range of activities, from sending out programmes and enrolling trainees, to ensuring that registers of attendance are available and certificates of attendance are printed ready for the Annual Review Of Competence Progression (the West Midlands Deanery requires 70% attendance at the courses). Box 5 gives an idea of the types of resources necessary to run such a course.

BOX 5 Resources needed to run an MRCPsych course

People

-

• Administrators

-

• Honorary clinical lecturers (one for each year of the course)

-

• Teachers

-

• Service users and carers

-

• MRCPsych Course Board

Physical environment

-

• Lecture theatre

-

• Small-group rooms

-

• Audio-visual equipment

-

• Flip charts

-

• Computers and projectors

Materials

-

• Handbooks for each year

-

• DVD of film clips as an aid to teaching

-

• Cataloguing of DVDs that can be used in teaching

-

• Course website

The 3-year programme

Box 6 gives an overview of the three teaching programmes that make up the MRCPsych course.

BOX 6 An outline of the programme of teaching

Year 1

-

• Lectures – the majority of teaching remains in this format; interactivity is encouraged:

-

small-group teaching – groups meet monthly

-

problem-based learning

-

fictional film clips used to depict situations and to stimulate discussion

-

online tutorial showing skills needed for interview skills

-

mock interviews are recorded and feedback received from service users, peers and facilitators

-

-

• End-of-module assessments

Year 2

-

• Lectures form the majority of teaching

-

• Revision sessions

-

• Small-group teaching of evidence-based medicine

-

• Small-group preparation sessions for clinical examinations

-

• End-of-module assessments

Year 3

-

• Lectures form the majority of teaching

-

• Revision sessions

-

• Small-group teaching of evidence-based medicine

-

• Small-group preparation sessions for clinical examinations

-

• End-of-module assessments

Course evaluation

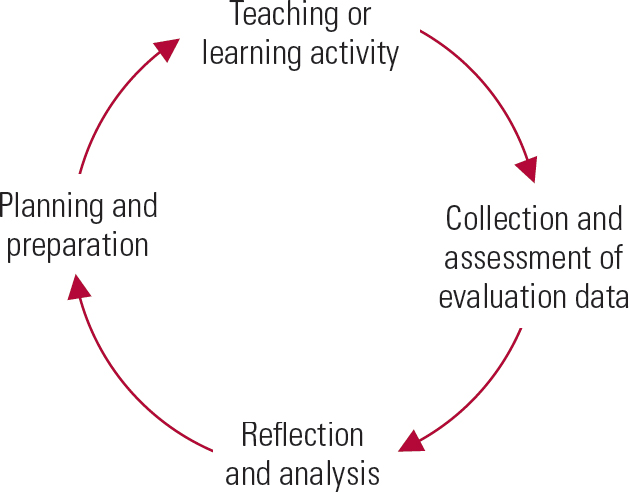

Any educational event benefits from continual refinement and this is illustrated in Fig. 2 (Reference Wilkes and BlighWilkes 1999). In common with other courses (Reference CoxCox 1996), at the end of each teaching session trainees are asked to complete feedback forms. The feedback is collated; individual feedback is given to teachers on the course and is also reviewed by the MRCPsych Course Board. Feedback from trainees attending the new style course, obtained from evaluation forms and provided by trainee representatives, suggests that the introduction of small-group teaching has been well received. Monitoring course attendance is an indirect way of assessing how trainees value a course and the course administrator recorded an increase in attendance numbers with the introduction of the new course.

FIG 2 The evaluation cycle. (After Reference Wilkes and BlighWilkes 1999, with permission).

Other ways of evaluating MRCPsych courses include keeping systematic information regarding the numbers of trainees passing the College examinations. Useful feedback on individual teaching sessions can also be provided by having another teacher sitting in on a session and giving feedback to the person teaching.

Conclusions

Running an MRCPsych course is a complex and time-consuming task. The principles described and examples given may be of interest to experienced course organisers and may be helpful to those taking on the role of course organiser for the first time. In the UK, multiprofessional learning is going to become more common in the National Health Service (Department of Health 2001) and is likely to become a feature in MRCPsych course teaching. There is a huge potential for e-Learning to become much more important than delivering teaching face to face.

Variations in MRCPsych courses mean that teaching strategies must be chosen that are appropriate to the size of the course and the limitations of the teaching environment. For us, the experience of introducing new ways of teaching such as small-group work and the feedback from this have been extremely positive. New strategies for teaching are being adapted throughout medical education and MRCPsych course organisers have the opportunity to avail themselves of these.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

-

1 Andragogy:

-

a describes the way that adults learn

-

b differentiates between the way that men learn and the way that women learn

-

c has been described by Kaufman's three principles

-

d has no impact on a medical education programme

-

e discourages learner involvement in the learning process.

-

-

2 Kolb's cycle:

-

a is based on surface learning

-

b consists of six stages

-

c is based on knowledge creating an experience

-

d builds on the work of Jean Piaget

-

e depends on the age of the learner.

-

-

3 Regarding MRCPsych courses in the UK:

-

a they are an optional component of postgraduate medical training in psychiatry

-

b they are well standardised in format and delivery

-

c they are coordinated centrally by the Royal College of Psychiatrists

-

d the Deaneries and local education providers are responsible for the delivery of the course

-

e PMETB devised the curriculum for the course.

-

-

4 Small-group teaching:

-

a is ideally suited for understanding and synthesising information

-

b is less effective than traditional teaching methods

-

c is best when it is dominated by the facilitator

-

d does not encourage quiet students to contribute

-

e has little impact on resources.

-

-

5 Which of the following has no role to play in the creation of an MRCPsych course:

-

a problem-based learning

-

b lectures

-

c communication skills training

-

d clinical case supervision

-

e service user and carer involvement.

-

MCQ answers

| 1 | a | 2 | d | 3 | d | 4 | a | 5 | d |

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.