Book contents

Chapter 1 - Winnie Mandela and the Archive: Reflections on Feminist Biography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 15 April 2021

Summary

When I was in primary school and living in Nairobi, we lived next door to a girl called Aida. Aida was not her real name, but all these years later I feel a feminist duty to protect her, given all that was said about her. This in many ways is the purpose of this story: to reflect on the duty of care feminists owe the women who populate the archive – and those who may yet enter.

Aida was older than I was. She was about 16 when I was eight. She lived with her father and that was it – just the two of them. I was in that phase of childhood in which certain older girls seemed impossibly glamorous. Aida was this sort of a half-grown girl who fascinated me – an almost-woman who still had the leisurely pursuits of a child.

Aida was Ethiopian, and she had large, exaggerated eyes that seemed exotic to me, but which are common on the streets of Addis Ababa. And she had a long and large and proud nose, which was always turned up. Her features were softened by her mouth, which was small and pouty, like that of a child. The thing about Aida was that everyone knew she had been pregnant, though no one was quite sure what had happened to the baby.

I didn't care, of course. The rumours didn't make a lot of sense to me, and what she gave me in time and attention far outweighed whatever it was that she had done to get pregnant and then unpregnant. So, I did what eight-year-olds do best. I followed her around without shame. After all, I was too young to be embarrassed by how much I longed to be like her.

Sometimes she would paint my nails and put lipstick on me. I always wiped it off before my mother got home from work, and if Bathsheba – the woman who looked after us – called me, I would move even more quickly. Bathsheba was under strict instructions to ensure Aida and I stayed apart. My mother hated me being in Aida's house.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

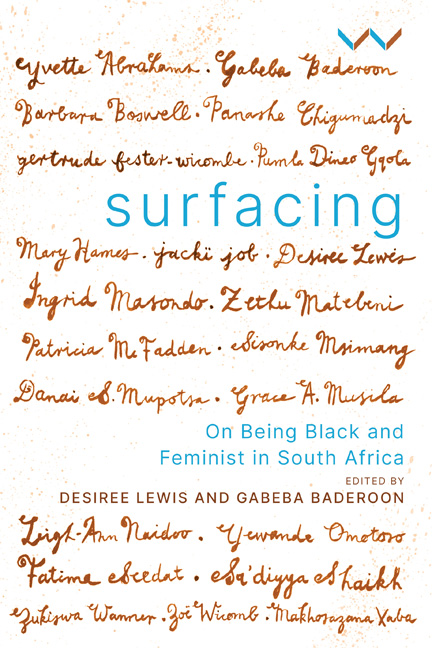

- SurfacingOn Being Black and Feminist in South Africa, pp. 15 - 27Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2021