Absent Image

William Hogarth produced two pictures: The Enraged Musician and The Distrest Poet. There was meant to be a third, a painter in some sort of mood. This essay reads the two pictures of 1736–41 to speculate about the absent third. What it finds in the two images, it finds in all of Hogarth’s art: a wit of incongruity, ambiguity, and inversion. The wit supports a satire that, drawn loosely from virtue theory, addresses liberty and justice in a society of professions feared for their foreign taste and imposture. Asking to whom the moods belong, I answer first, to the musician and poet of title; but second, as spreading by ear and eye through the dramatic scene finally to reach the maker of the picture. Why does a painter show a moody musician and poet if not also to reflect on himself as a sibling artist? And if his mood is already implicated in the two pictures, wouldn’t a third be redundant?

While drawing from recent scholarship, I focus more on the first readers of Hogarth’s art: the likes of John Trusler, George Steevens, Georg Christoph Lichtenberg, and Charles Lamb. They all contributed to authorizing the anecdotes regarding Hogarth’s art and life as collected in the 1780s under the leadership of John Nichols, longtime editor of The Gentleman’s Magazine. The anecdotes were characteristic of an age that found Hogarth moralized. This did not automatically mean a reduction of his moral pictures to a crass moralism or pedantry regarding the true, the good, and the beautiful. To so reduce the pictures would be to miss the threaded lines of the satire, the micrology of the wit in the details, the shifting targets, the sea- and scene-changes of mood, prejudice, and perspective. Today, the formal architecture and furniture of Hogarth’s pictures impresses more than the array and display of nasty prejudices regarding race, gender, and nationality. Nevertheless, because this age of liberty and wit took on prejudice itself as a core issue for modern philosophy and aesthetic theory, there is purpose still to looking and reading in this period. What, I am asking in the background, can be rescued not by drowning out the prejudice or by hiding it from view, but by allowing the pictures to serve as a critical mirror for our own troubled times?

Musician Inside and Out

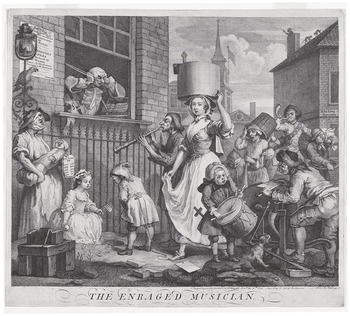

Hogarth’s picture of an enraged musician was described first off as a musician provoked (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 William Hogarth, The Enraged Musician, 1741.

The provocation regards a well-garbed string player arrayed with a coat decorated with frogs, a bag-wig, solitaire, and ruffled shirt. He stands inside a well-to-do house not far but psychologically distanced from the street life outside and below. Seeming to have leapt up in fury from his chair, he is said to allude to Apollo, leading one to expect that his instrument of well-tuned strings would issue harmonious sounds – were he only in a better mood. But perhaps he is also a more suspect idealizer, a Terpander who systematizes simple compositional rules or a Timotheus doing double duty in a noble house distantly related to the court of Alexander the Great.

He is anyway distracted by what comes from outside, and most pointedly by a wind player read as a satyr figure: a Marsyas, Pan, or Orpheus figure who has learned to dress in the bedeviled or bohemian garb of those branded indiscriminately as Jew, Italian, French, even German – in a land ruled by an Hanoverian king. Some describe the wind player as existing between man and monkey to connote the mashing associations of an organ-grinding. This fits the fact that he is not a native but an outsider of common descent, a pied piper of the low who has joined up with all the street traders known as the criers as they produce their cris de Londres with a foreignness that only more provokes the insider-musician. Yet the twist is that the housebound man of strings is no native either, but an Italian of educated taste. So what has his high-class rage to do with the low cues of the street scene? Might we read the picture-maker as expressing his own rage at a foreign taste spreading as the plague of all plagues over London – and on one house in particular?

That both the string and wind players are foreign was how, against the background of John Gay’s Beggar’s Opera, Hogarth commented on the dominance of Italian music on the English stage. The foreignness of the educated string player stands for the Italian music favored as the town’s most recent taste, while the wind player, with his disturbing physiognomic complexion and clothing, stands for those who enter London as improvisatori and virtuosi – a procession of rough travelers with Italian contours. The social commentary addresses the impact of all that is foreign in the capital city: the atmosphere, say, of French airs and graces of pomposity from persons wanting nothing to do with the criers caricatured already by foreign artists living sometimes in London. Two caricaturists have been identified: a Dutch-born painter and engraver, Marcellus Laroon, for his The Cries of London, and a Venetian painter, Jacopo Amigoni, known, say, for his Shoe-Black. Borrowing from their images, Hogarth shows nothing in the picture as homespun. Italy, France, the Netherlands: The differences from abroad make no difference. What then makes the difference for the one inside the house who evidently wants nothing to do with what loudly confronts him right in front of his eyes?

Perhaps the insider fears an identity under a foreign branding: ‘I have disguised my foreignness as you have not’, he thinks with all the high-strung anxiety of the would-be assimilated, as he stares in horror at the piper – who retorts with his straight pipe: ‘Ha! So you think!’ The pathology and provocation born from fears of the foreign, where one musician looks at himself mirrored in the image of his enemy, leads to a broader hermeneutical point. Questions of indiscernibility are not resolved by fixing the figures in this scene with unique or singular identities. One might be tempted to do this with an exactness of reference and allusion to places and persons of the period. Yet naming names or engaging an iconographic exactitude detracts from how Hogarth’s wit moves through eye and ear to effect turns of mood and perspective on the identity of each individual. I take a cue from the German art historian Werner Busch who, following Lichtenberg, asks interpreters to keep the wit of the picture open to a productive ambiguity and not to close it down. The cue asks us to look, and then to look again, through the evident prejudice for a more subtle target of social satire: given a painter professing and confessing about the modern lives of siblinged artists.

Who’s Who

The Enraged Musician is read by most according to an anecdote regarding a Mr. John Festin, declared eminent for his skill in playing upon the German flute and hautboy, and much employed as a teacher of music:

To each of his scholars [Festin] devoted one hour each day. ‘At nine o’clock in the morning,’ said he, “I once waited upon my lord Spencer, but his lordship being out of town, from him I went to Mr. V-n. It was so early that he was not arisen. I went into his chamber, and, opening a shutter, sat down in the window-seat. Before the rails was a fellow playing upon the hautboy. A man with a barrow full of onions offered the piper an onion if he would play him a tune. That ended, he offered a second onion for a second tune; the same for a third, and was going on: but this was too much; I could not bear it; it angered my very soul – “Zounds!” said I, “stop here! This fellow is ridiculing my profession; he is playing on the hautboy for onions!”’

The anecdote pertains to one Pietro Castrucci, an Italian who, arriving in London with instruments and skill, discovered to his dismay a lookalike on the street: a Mr. Festin. But if Castrucci is the enraged virtuoso of the stringed instrument, then Festin is either the same person in a false identification or the flautist enraged at being mistaken for a hautboy player blowing tunes for onions. So what we have now are two enraged musicians, or, better, one enraged figure compounded by contrary characteristics: of strings and wind.

Jeremy Barlow runs through all possible candidates for the identity of the enraged musician: the more, the better. The nineteenth-century Grub Street critic George Augustus Sala surmised that the enraged musician was either the great composer of foreign birth and native talent, George Frideric Handel (without his umlaut), or else the German composer Johann Christoph Pepusch. But then Sala turned to the war-cries as les cris de Londres, the main topic of his essay of 1892, as spreading across the scene with a ‘Buy, Buy, Buy’ of great consequence and even greater volume. This is my cue to stress the dividing line between the figure who stands quite alone inside the house and the entire mob chorus that clatters to produce all the agonies of an auricular torture that, with foreign spice, Charles Burney described as a polissonnerie. By the French term, Burney captured a marketplace of prosaic trade capable through translation of transformation. Everything foreign in this highly contested public sphere was re-spun to be homespun for a new British art. The result was a picture from Hogarth’s English hand.

Barlow follows the juxtapositions of high and low terms between violin and fiddle, oboe and pipe in a shifty pattern between civilization and roughness. On the street, the pattern is spread out further through the suggested contrast of the secular dissonance of workers’ tools with the claimed harmony of a sacred building’s chimes and bells. Along with this comes the dialectic between industry and idleness which, sourced to Hesiod’s Works and Days, reinforced the inequality of those who rested on rest days while others worked. The hoisted flag in the picture suggests the feast of May Day when, traditionally, in praise of the Virgin Mary, everyone danced around the maypole with red ribbons to make all things seem not as they ordinarily appear. But who dances in this picture? Certainly not the lone musician. If the day is given over to the criers, then it is the commoners who turn their daily labor into a play-within-a-play, their commonplace tools into instruments for a new musical art, and their street rage into a worker’s hope for a new May Day tomorrow.

All the World a Stage

A poetic epigraph accompanies the scene: With thundering noise the azure vault they tear, And rend, with savage roar, the echoing air: The sounds terrific he with horror hears; His fiddle throws aside, – and stops his ears. The first overseers of Hogarth’s art tell that the adagios and cantabiles of the string player have procured him the protection of nobles – suggesting that the enraged musician is not himself of the nobility but in the employ of a noble patron. Perhaps, however, the noble patron is only a would-be bourgeois gentleman who wants lessons in the divine science of music’s principles. Still, who knows, since the patron is not on view. We read that the musician, before becoming enraged, wants to teach his principles through his practical skill on a well-tuned instrument in accord with the open crotchet-book on the music stand. Presumably then, the house, not being his, places him in some sort of waiting chamber. But why, if waiting to teach, is he so rattled by the racket in the marketplace? Does the waiting express his insecurity as a person of professions: that his position, even when or because protected by a patron, is highly precarious? Remember from the Festin report: This fellow is ridiculing my profession. Without social security, he is no person of property. Without property, is he a nobody who has become a somebody who can’t look at himself in the mirror? Why can’t the musician take a blind eye or assume a deaf ear to his surroundings?

Scholars like to identify the exact street address of the scene as St. Martin’s Lane given the church shown and the buildings known. Again, the exactness matters less than the impression that something is awry in the street scene: a modern architecture of this little Babel that destabilizes a professional musician aspiring to the condition of harmony. The stringed instrument he is about to play or has already played is not played in this moment. The moment is of a significant interruption. Some see the musician as shouldering his violin and flourishing his fiddle-stick. But what is shown is the instrument perched uncomfortably on the window-sill with the bow only just about held, as both hands are raised to cover his ears. The ear covering suggests the musician’s desire to stop the noise of a beggar’s opera reaching him, as this opera is suggested by the smudged poster hanging on the outside wall of the house. The decayed poster, advertising the Sixty-Second Day of Gay’s play by the comedians of the Theatre Royal, clues us into the present and even future state of the arts as daily played out on the walls of a stratified society. If Hogarth was putting on trial a stage that is now all the world, so, too, in his The Enraged Musician. While the insider musician glares at the outsider wind player, the street people cry for a London that can always put the king on trial. The bored parrot, perched on the street light of illumination, seems repetitively to screech out what he reads from the lower corner of the advertising poster: vivat rex! vivat rex! With a beggar’s opera restaged on the street, is this a poetic call for a justice through revolution or restoration, neither or both?

Sound Drowning

When the inside musician opens the shutters, the amplified noise is said to kindle his rage. But with more air comes more combustion: The noise spreads like the rush of many waters. With the torrential waters, the noise fuses with the dirt, dust, mud, and blood from a market labor cut and bound by unpitched instruments: pots and pans, sticks and stones, hammers and knives. In the crowd, Gay’s ballad singer stands with her petrified baby while holding up the sheet music for a late seventeenth-century lament: The Ladies Fall. A child nearby plays with a noisy rattle; another pees; a drummer boy beats out of time. A person of age plays a ram’s horn that seems to lead another tradesman to cover his ears. The hell-hounds – the dog, horse, cat, and monkey – accompany the merchants and peddlers dealing at a high pitch and in a fog of dust – Dust, ho!

Beneath the window of the great house, the crooked-nosed wind player stands with his mouth instrumentally full. It is he who most catches the glare of the musician inside. He is described as blowing his horn with such force that the noise could shake down the walls of Jericho. This alludes to the ram’s horn and trumpet of the Israelites and to the early ekphrasis for the ancient city of Thebes. After the harmonious string-playing of Amphion, the heavy stones, carried by his twin brother, jumped lightly into place to erect a city with firm walls. Today, however, in Hogarth’s London, the winds of history persuade the bricks to run away as paper bills of money render the bricks pointless. Whistling between the cracks is Solomon’s Proverb 25:28: Whoever has no rule over his own spirit is like a city broken down, without walls.

Lydian Measure

Another feast (festin) to feed Hogarth’s picture is Dryden and Handel’s 1697/1736 ode Alexander’s Feast, or the Power of Music. The festin for Cecilia rings out Softly sweet, in Lydian measures, soon to soothe the soul to pleasure. But who trusts a Lydian measure? The enraged musician rapt in Elysium at the divine symphony is awakened from his beatific vision by noises that distract him. The more the distraction, the more Milton’s lines from Paradise Lost take hold: An universal hubbub wild, Of stunning sounds, and voices all confus’d, Assails his ears with loudest vehemence.

Echoing Genesis 4:21, Dryden addressed music’s double way of tuning and untuning the skies and the earth: His brother’s name was Jubal. He was the father of all those who play the lyre and pipe. For Alexander’s feast, the old musician Timotheus was placed on high amid the tuneful quire while with flying fingers touched the lyre. All around, the listening crowd admired the lofty sound. In Alexander’s court, Timotheus was hired to purge corporeal sickness and perverse habitudes of the brain – a hard daily labor: he lost not any one hour in the day. Taking double pains, he demanded double compensation: first to unteach the court-nobles what they had been taught amiss, and then to instruct them aright. The double pain drew from Horace first, and then from the witches’ brew of Shakespeare’s Macbeth: Double, double toil and trouble. The toil and trouble was not, as usually it was, a mischievous wife, but a king engaged in a battle between honor and vanity: Honour but an empty bubble; Never ending, still beginning. With Alexander refigured as the modern monarch: the ravish’d ears assumed the God (Bacchus) to be affecting always a nod. Evermore vain, the king fought battles over and over again, convinced that the divine hand and presence was everywhere for him, even in the hautboy’s breath. When, however, with shrill notes of anger, the double double double beat and cries were heard, hark the foes come – suddenly all was exposed on the bare earth. With downcast eyes, the king’s mood descended to a melancholy so grave that Timotheus had now to soothe him: Softly sweet, in Lydian measures. With breathing flute and sounding lyre, the soul swelled to rage and kindled to soft desire. At this moment, the divine Cecilia descended as the Inventress of the vocal frame. With Nature’s mother-wit, and arts unknown before, she drew an angel down, while old Timotheus raised the mortal to the skies. For the king who remained uninstructed, the old aulete won the prize. Whether the string player would now yield or share the prize with Cecilia was of no concern to her. She was named to be blind to the vanity of such rewards.

What, now, does Cecilia, as Inventress of the vocal frame, bring to Hogarth’s picture? In writing his ode for St. Cecilia’s Day, Dryden gave Cecilia the tuning fork: from heav’nly harmony, this universal frame began … through all the compass of the notes it ran, the diapason closing full in man. … within the hollow of that shell that spoke so sweetly and so well. Hogarth, made now into the inventor of the picture frame, took the vocal frame to turn a street noise to a silence of a music renewed. From a paradise lost to one regained, he used the patronage of a feminine figure to draw Dryden’s poetic breath out of Milton’s tumult and confusion all imbroild in a discord with a thousand various mouths. Despite the sweet reinvention, however, the irregular Lydian measure suggested that his divining rod, once given to Bacchus and Moses, retained a cutting satiric point.

Irregular Dance

Those who have looked at the May Day milkmaid in Hogarth’s picture have said that if ever she caught anyone’s attention, something perhaps sweet or good would come to the ear. She stands out from the others with a curvy naturalness of physique corresponding to the naturalness of her voice. Her voice is neither learned as an in-house music of strings nor acquired as a streetwise skill of suspect winds. But who is she and for what or whom does she sing?

In his 1753 treatise The Analysis of Beauty Written with a View of Fixing the Fluctuating Ideas of Taste, Hogarth did everything not to fix the ideas in the wrong pictorial way. He instructed those producing a visual object of a great variety of parts to let the parts be distinguished by themselves, by their remarkable difference from the next adjoining. The movement of parts in pictures is akin to that in passages in musick and paragraphs in writing. This way, not only the whole, but even every part, comes better to be understood by the eye. One moves one’s eye around a picture, as in theatre or dance, cued best, he now added, by lines from Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale: – What you do, still betters what is done. – When you do dance, I wish you a wave o’ the sea, that you might ever do nothing but that; move still, still so, and own no other function. A wave of the sea promised a motion even in the stillness, but only, Hogarth maintained, if straitlaced academics ceased abusing classical principles to produce from ideas of fixity and clarity only a monotony. While the senses delight in sameness, the ear should not be fixed on a monotonous note nor the eye on a dead wall. Yet movement had its own constraint: While delighting in variety, crowds ought not to amount to gluttony. For crowding, Hogarth was reckoned a genius: no messy mass; no loss of design or composition. Hogarth, himself, described his picturing in terms of a (Dryden-like) shell, with its inner and outer surface, around which one walks in the imagination through its contrary perspectives. The eye was to follow the imaginary circular threads and spinning tops.

Hogarth brought the movement to a culminating line: the S-line of beauty. It gave curve and contour to the design, allowing the eye to wonder as though wandering along a winding serpentine river. But with the serpentine, we reach Eve’s irregular approach to Adam, or his to her, to disorder the harmony that Hogarth found in the Cecilian achievements of Renaissance painting and poetry as well as in the milk delivered by the Virgin Mary of May Day. From Milton’s Paradise Lost, the skillful steersman on the boat who wrought nigh river’s mouth, draws his tortuous train, curl’d many a wanton wreath, in fight of Eve, to lure her eye. The irregularity of the measures taken across the water has recently been read by Abigail Zitin as a turning of the wanton wreath to the wayward dance of a Gypsy, whose steps, like those of an Arabian horse, are in accord not with Apollo’s classical principles but with a popular country dance which, from Milton, shows mazes intricate … regular … when most irregular they seem.

The S-line in The Enraged Musician that gives the curve to the milkmaid on May Day is put into the hands of Eve, the Virgin Mary, and Cecilia, so that the vocal frame can breathe all sorts of passions into the hubbub of noises – even, as Dryden told, into the hautboy’s pipe. As Dryden’s Jubal strikes the corded shell, the list’ning brothers and sisters gather as the irregular maze turns to something musically beautiful. Of all the figures in the scene, only the insider musician cannot join in: So professing divine principles with covered ears, he alone makes no music. For the frontispiece of his Analysis, Hogarth placed the curved S-line and spinning shell into a stilled pyramid stabilized by the divine geometry from Isaiah 19:19–20. The carrying walls of the house give off a double perspective, inside out and outside in. As the musician’s rage of title attaches to the insider, the man of profession cuts his own strings to become the butt of Hogarth’s satire.

Black Joke

When tunes were being traded for onions for a suspect commerce in London, so too the Black Joke. Typically smutty, the joke was filled with either a smelly excrement or the sticky substance of illicit sexual intercourse. Barlow notes this to track the constant sex-for-money exchange in Hogarth’s design of social prostitution. So pervasive the spread of diseased sperm that the virgin was turned white to black, after which the outpouring of excrement forced men of ev’ry profession into the city sewer. In 1720, when the joke first found its way into print, it mocked the mathematician, surgeon, chemist, lawyer, and priest, each for preferring to love a black joke and a belly so white than to engage in honest labor. Onto the blacklist was then added the painter who artfully penciled his strokes, If he had his own will, he’d paint nothing but jokes. But black jokes and bellies in white. And then the musician who from morning to noon, Singing no other song, playing no other tune, But the black joke and the belly so white: Both Handel and Purcel[l] for this he would flight; He’d sing it all day, and he’d strum it at night On the musical joke. From the black joke soon came the joke made white for the prudish, green for the youth who imbibed a vino verde, brown for the worn and miserly; and red, of course, for those enraged. It was an old color scheme, found already in Shakespeare’s Love’s Labor’s Lost, when the loss was felt in every part of the (civic) body.

Any failure to turn a black bile of melancholy to something white was said to owe to too many wigged eminences of grey-hair capitulating to flattery and applause. The applause was a claptrap, literally an air trapped by hands. But poetically, as Samuel Butler wrote in Hudibras, it was a double disease coming from a badly tipped pen(is), when Moses’s law of circumcision and Socrates’s laws of circumscription were misread to remove all differences among persons whatever the color and metal of their blood. The original black joke, sent from Dublin to London, refused to blame the man in favor of a human nature pulled, as in the working of a joke by a rope, to equalize across the globe the situation the same for Prince, Priest, or Peasant.

Attacking the democratizing tendency, Alexander Pope offered his Imitations of Horace in 1737 to forefront the black joke in a mock epic-epistle targeted at the insecurity of persons of professions, from professor to poet. Moving biblically between the fat and the lean, he addressed his patron – Ad Augustus – to condemn the leveling-out of culture when aristocratic taste merged with that of the noisy mob. The cacophony is at war with harmony. But when the harmony turns to a vanity, its bark conveys on fame’s mad voyage by the wind of praise. The storm takes the steersman off course: For ever sunk too low, or born too high! Fearing the fall down the social ladder, he contemptuously flatters all the more while condemning the mob’s violent song. Here, as in Hogarth’s picture, the noise is key to who gets the wit and who contracts the disease. In the satirical rearranging of the social class structure, the wit inverts established hierarchies head-over-foot without aiming to democratize the result to an all alike and everywhere the same. If the song is to be rescued, a farewell must be bid the stage, where the silly bard grows fat, on the inside, while the crowd outside revels in the remains to mortify the Wit. It is a farewell to the many-headed Monster of the Pit, to the poet and to the crowd who, while clatt’ring their sticks before ten lines are spoke, call for the farce, the bear, or the black-joke.

In Hogarth’s Enraged Musician, the call of the clattering crowd comes not only from the milkmaid but also from the knife and fork grinder, the cutler who concentrates on swiping his large chopping instrument back and forth. (There were many cutting caricatures in this period of cutters and grinders.) One writer described Hogarth’s cutter as eliciting sparks of fire. But to what point? If figured after Marsyas’s flayer, his task would be to skew the wind player on behalf of the Apollonian string player. But wouldn’t this make him a Judas, an executioner cutting down one of his own kind? Maybe he wants to slay the string player instead with an irregular rhythm for a harmony gone awry.

Deafening Silence

Early readers of The Enraged Musician found a particular wit in Fielding’s quaint observation that the whole of this bravura scene is so admirably represented, it deafens one to look at it. To be quaint was to be charming and old-fashioned. Fashions, old and new, were the target of the social satire. One thought from the Renaissance paragone is that if one covers one’s ears, the picture’s muteness is laid bare. The muteness is a limit and an advantage. When it is stressed that no visual medium can mechanically turn silence to sound, the visual medium is saved by its capability to express a divine silence without noisy interruption. But something else was on Fielding’s mind. He wanted to drown out London’s noisy cries, to become deaf to them, to release his recollection of Lisbon’s delicious … concord of sweet sounds of seamen, watermen, fish-women, and oyster-women. Hearing something different in memory, he came to see something different in Hogarth’s picture. The scene-change mattered the most.

When Hogarth’s enraged musician covers his ears, he opens his eyes wide to the dirty city. Does he cover his ears to see more or less: as a wise seer or as an ass? Hogarth’s point was for the scene to play out like a wordless dumb show akin to Hamlet’s exposure of the impostor king. Deafening in mood and impact, the play-within-a-play was needed by persons of the highest rank who, in Fielding’s terms, stubborn and enraged against the mob, remain oblivious to the social ills. Hogarth and Fielding, like Pope, take on the highest rank hiding behind the highest walls.

Distressed Poet

We are not finished with the enraged musician, but it is time to bring the distress of Hogarth’s poet to account (see Figure 1.2). Again, we turn to Pope’s Horatian epistle to discover the dear delight to Britons farce affords, when the farce, once the taste of mobs, is now of lords. Figuring taste an eternal wanderer capable of flight, Pope invoked Apollo to judge the fluctuations all around from heads to ears, and now from ears to eyes. He called then to the luckless poet! to stretch his lungs to roar, so that the bear or elephant shall heed thee more. But does the poet have any chance of out-sounding all the throats the gallery extends, as all the thunder of the pit ascends? Is the poet, titled for his distress, entitled to his suffering? Did Hogarth’s sympathy lie with the distressed poet as with the enraged musician constantly to question the sympathy?

Figure 1.2 William Hogarth, The Distrest Poet, c. 1736.

Hogarth’s poet occupies an interior space, another waiting chamber. But for what is he waiting? He is young and lives high up in an impoverished garret. With a sloping roof, the space is described as a Porridge-Island sky-parlour. The poet sits at a table partially dressed as though on public view. His wig provides no security. He scratches his head, distracted from the muse but not by her. He tries but fails to write a poem in mock homage to the Grub Street Journall, of which an issue lies on the floor. The title for his poem Upon Riches replaces a discarded title: Poverty. A Poem. He contemplates the uses and abuses of the wealth that being a poet professionally affords. His choice is Herculean: to strive for art’s spiritual rewards or to secure his ascent up the social ladder by compromising hand and spirit. Were he only to follow the principles of poetry laid out in the books, he would find his way to the gold marked by a withered map pinned onto the wall: A View of the Gold Mines of Peru. But who places trust in such a map?

The interruption from the street is a single dismal demand of a milkmaid who wants to be paid. Having walked up many flights of stairs, no sweet concord comes from her lips. If there is an S-line in the picture, it is arguably drawn in the thread with which the poet’s wife mends his ripped coat. One reader sees her sitting with all the silent and deafening poverty on display: the cracked plaster, the shattered glass, the uneven floor, the empty cupboard, bucket, and saucepan, the flameless logs, the hungry dog, and the baby who, with covered ears, cries out for all the great misery. But this reading little gels with the anonymous letter (though many suspect Hogarth’s pen) sent to the editor of the Grub-Street Journall, which so coldly describes a penniless bard, not yet a man of profession, complaining of a disinheritance that has left him in dire need. A bauling milk-woman at the foot of the stairs usually raves in Billingsgate. Sitting on a broken chair, the wife botches the bard’s breeches. A cat sits on the thread-bare coat. A bard sitting at his desk and scratching his head endeavors to draw a few fustian verses from hard-bound brains.

At the time of issue, George Steevens identified the poet described in the letter as Lewis Theobald, whom, in the same Grub-Street journal, Pope condemned as a bad plagiarizer or double falsifier of Shakespeare and Spenser. Regarding every line from Theobald’s The Cave of Poverty, Pope had outmatched it. Rewriting The Iliad as The Dunciad, Pope had exposed the error in the entire Theobaldian mischief of misery, borrowing from Shakespeare’s comedy of errors and from Ben Jonson’s comedy of humors, where living by the prowl, and belly too, wit became the true witness of the pen. If there was poverty in the poet’s belly, it was meant to feed a true invention as opposed to a predigested line.

Recalling his youth, Hogarth offered anecdotes to show how a healthy rivalry among persons of professions could turn black-to-white to a useless envy of which the result would be a bad theft of another’s property. He read in Gay’s Beggar’s Opera how all professions berogue one another, where beroguing fittingly caught out those who imitated to win contra those who imitated to a good end. Some painted and some flattered the taste of the town’s painters. Devoted in youth to portrait painting, he made no money. Rethinking his skill, he claimed modern portrait painting a common commerce on Today Street, an outdated manufacture, to which he would respond with a social portraiture of less cost in every sense to commoners. And the result? Penny-prints described as composed pictures on canvas or serialized engravings on modern moral subjects. Acknowledging prototypes from France, Italy, and the Low Countries, his low art would come to rank in Britain as of the highest class. One high class of foreign taste would be displaced by the taste of his own homespun British art.

Knowing The Beggar’s Opera, Hogarth knew the risks of satirizing the establishment, of causing offense to well-bricked houses of art and entertainment: Cautious and sage, Lest the Courtiers offended should be: If you mention Vice or Bribe, ’Tis so pat to all the Tribe; Each cries – That was levell’d at me. Gay leveled these cries of London knowing that his Black Moll was sitting at her accounting table dispensing the terms of social and poetic justice. If the drama offered no harmonious settlement of marriage, it would leave criminals in danger of being either hung or transported. Standing between two lovers (art and success), whom or what did one choose? So would Hogarth’s distressed poet make the Herculean choice easy for himself: to be or not to be a good plagiarist? This was the question on the table for every beggar playing a part in the opera and masquerades of the town.

Hogarth’s image of the poet was accompanied by the usual pithy line and verse. One thought was to use lines from Samuel Johnson’s 1738 poem London, written, from hunger, in sly homage to Juvenal’s Third Satire about a city where, from white to black, foreigners bankrupt and pollute. The lines chosen read: Since Worth, he cries, in these degen’rate Days, Wants ev’n the cheap Reward of empty Praise; In those curst Walls, devote to Vice and Gain, Since unrewarded Science toils in vain. But these lines were erased in favor of lines drawn from Pope: Studious he sate, with all his books around, Sinking from thought to thought, a vast profound: Plunged for his sense, but found no bottom there; Then wrote and flounder’d on, in mere despair.

Mood and Mind Changes

Prefacing Joseph Andrews, Fielding declared Hogarth ingenious: It hath been thought a vast Commendation of a Painter, to say his Figures seem to breathe; but surely, it is a much greater and nobler Applause, that they appear to think. Combining burlesque and caricatura, Hogarth purged spleen, melancholy, and ill affections. No bad mood was left monstrous or ridiculous if it gave way to a thought of something different and better. Fielding compared picturing with writing to proclaim genius the wit of incongruity, where contraries exposed the falsity and the truth of each side. Where, then, did the wit lie? Alone in the micrology of telling visual details. From something subtly or satirically seen could come something newly heard and newly thought.

Translating Hogarth’s Analysis into German in 1753, Christlob Mylius repeated the already high estimation of Hogarth as showing everything as though speaking and in action. The action was crucial. Hogarth claimed himself to put every character on trial in a realism of caricature that, against all flat copying, enlivened the body and face. The physiognomic movement was theatrical and scenic in the sense of spreading the thought through the entire landscape so as not to exhaust the mood in a lone portrait of an individual.

In his 1790s ausführliche Erklärung (descriptive explanation) of Hogarth’s art, Lichtenberg rejected the idea of merely chronicling the pictures. To do a picture justice was to engage ekphrasis – Bildbeschreibung – to bring the picture to life and mood (Laune). What the artist has drawn or shown (gezeichnet hat) must now also be said (auch so gesagt werden).

Charles Lamb’s 1811 essay published in The Reflector brought the early readings of Hogarth’s art to exemplary expression. Hogarth’s genius was Dryden’s display of thoughtfulness in even the oddest or lowest of faces. The thoughtfulness was a turn of the ugliness of face to a beauty or grace, achieved by Lamb’s essaying on Hogarth’s art from memory. By this, Lamb meant what Fielding meant: the taking of a readerly distance from the crowded visual evidence to free up the imagination’s movement of recollection and anticipation. Meeting the images half way liberated the free play of the mind necessary to grasp the wit, meaning, or sense, part to whole, in accord with Shakespeare’s Rape of Lucrece as a reworking of Homer’s ekphrasis of Achilles’s shield: For much imaginary work was there, conceit deceitful, so compact, so kind … A hand, a foot, a face, a leg, a head, stood for the whole to be imagined. Lamb declared the imagination the best weapon against an age raging after classification and analysis.

For his own ironically titled Analysis, Hogarth aimed to rescue beauty from scholars who footed the bill with predigested principles. What most do is show everything distinct and full because they require an object to be made out to themselves before they can comprehend it. Geniuses, contrarily, leave something wanting – not from a failure to finish but from respect for other minds to engage the artwork with a liberty of mind and imagination. When Lamb then declared that every detail tells, the telling was not meant to reach a point of exhaustion or complete explanation. He used the vulgar word ‘tells’ to destabilize Hogarth’s vulgar display of common things. What analysts condemned as merely vulgar, he aimed to rescue by appeal to Hogarth’s genius for detecting what escapes the careless or fastidious observer: the gradations of sense and virtue that stop one feeling merely disgusted at common life. The gradation was not aimed at reaching a high place where ideal forms of beauty only increased contempt for what is low. The ideal was rather to remain within what was real to show in the form all the subtlety of line and contour.

Lamb recalled youthful impressions of having seen the capital prints of the Harlot’s and Rake’s progresses hanging on the walls of a great hall in an empty old house. Although the stately atmosphere had encouraged him to experience the prints as noble, he had come to see the nobility as immanent in the pictures wherever hung. To estimate Hogarth’s art highly was to contradict those who equated the comic merely with a low intent, as though Hogarth intended only to raise a laugh. Risibility was not the ruling tendency, especially if it revolved into an equally crass seriousness. The essential turn was to find in the dirt and filth the sprinkled sense of a better nature, a holy water chasing away the contagion of the bad. Everything depended on the habit of mind and on changing the habit. Lamb recalled Juvenal and Shakespeare as exemplifying the change upon paper with a strength and masculinity then emulated by Hogarth in engraving upon copper. He remembered with pleasure hearing the reply of a certain gentleman on being asked which book he esteemed most in this library. Shakespeare, the gentleman replied – And next – Hogarth. Lamb now concluded: His graphic representations are indeed books: they have the teeming, fruitful, suggestive meanings of words. Other pictures we look at – his prints we read. The reference to other pictures was telling: for Lamb was reading Hogarth series-prints as others had not yet learned to read Hogarth’s paintings or the paintings of others.

Of all the prints, Lamb selected The Enraged Musician as exemplary. No face was boring or merely riddled through with meanness or vice. Each countenance had a poetry and mood of intense thinking, even, he noted, the Jew flute-player and the knife grinder. Of what possible interest to viewers would it be for a painter to depict only an ugly and outcast figure? Wouldn’t such depiction issue only a vacancy? He answered that the perfect crowdedness unvulgarized every subject in the scene, excepting, as I am adding, the lone musician who stands unchanged far from the madding crowd. Like the distressed poet or Dryden’s king, the man, secluded from all others, had become a man of too much profession and too little confession.

Consistent with his reading of the scene-changes and sea-changes of social taste and prejudice, Lamb refused the ideal standpoint, preferring to admit to his always imperfect sympathies. In a short essay on the imperfection of intellect, he confessed with disarming candor to not being able to like all people alike:

I confess that I do feel the differences of mankind, national or individual, to an unhealthy excess. I can look with no indifferent eye upon things or persons. Whatever is, is to me a matter of taste or distaste; or when once it becomes indifferent, it begins to be disrelishing. I am, in plainer words, a bundle of prejudices – made up of likings and dislikings – the veriest thrall to sympathies, apathies, antipathies. In a certain sense, I hope it may be said of me that I am a lover of my species. I can feel for all indifferently, but I cannot feel towards all equally. The more purely English word that expresses sympathy will better explain my meaning. I can be a friend to a worthy man, who upon another account cannot be my mate or fellow.

The more Lamb saw the unvulgarizing of the countenance of a Jew or Negro, the more he expressed his fear of a mobile society of acculturation and assimilation that denied natural differences among peoples. He described the Jews who, amid all the Christianizing proselytism, failed to conquer the Shibboleth and celebrated each year those who passed through the Red Sea. He saw them as a piece of stubborn antiquity. Lamb’s prime target, however, was the reader, the one who equalized truth to a leveled sameness through an abstraction of equality. Lamb threw the question on the table so central to his age and to all ages thereafter: whether formalists of equality who, as a Religio Medici mounting all claims upon the airy stilts of abstraction, could change the sentiments or habits so deeply embodied in us all. What formalism abstracts in philosophy, so as to float far above the streets, art brings down to effect changes of perspective and mood. What, he asked, stopped the formalists becoming proselytizers of equality; the unconverted theorists of a liberalism that, in abstraction, left all prejudices in place? The question as so formulated belonged to an age claiming liberty, equality, and universal toleration, an age attempting to justify a form of judgment untethered from the pre-judgment of raw prejudice.

In another brief essay, ‘Blakesmoor,’ Lamb proclaimed Ovid’s verbal depictions less vivid than a tapestry visualizing Apollo’s culinary coolness when divesting Marsyas of his skin. Did he really prefer images to Ovid’s words? Or was he bringing attention again to Ovid as the true master of metamorphosis? In ‘A Chapter on Ears,’ he raged against the insufferable modern music that made him want to cover his ears. Feeling like Odysseus before the sirens, he claimed no ear for music: no talent and little liking. His claim to be unlearned was strategic and borrowed: a defense of the unlearned ear to satirize the falsely learned ear! As Joseph Addison had written a century earlier: Musick is not design’d to please only Chromatick Ears, but all that are capable of distinguishing harsh from disagreeable Notes. A Man of an ordinary Ear is a Judge whether a Passion is express’d in proper Sounds, and whether the Melody of those Sounds be more or less pleasing.

Lamb claimed to be most insulted by the new purely instrumental music that expected him to listen as though a viewer in front of an empty frame: Why should he have to make pictures from scratch or invent extempore tragedies to answer to the vague gestures of an inexplicable rambling mime? Willing to go halfway, he refused to go all the way. In short supply (in every sense), he said, most house music today is empty and pompous in its monotonous repetition of gestures. Looking at the enraged musician, Lamb stood not with the high houses of music: They should, with his exaggerated thought, be silenced. Only by moving through the purgatory of common-life sounds on the streets did he reach his conclusion and, as he added, his paradise.

We know that wit is no excuse for the proliferation of prejudice, but what if wit serves a satire that, by confessing to the prejudice, exposes it in those who refuse to admit to it? May we read Hogarth’s pictures as offering a satire on confession quite as much as on profession? To confess? To profess? Was this not the to be or not to be question in Hogarth’s age, the question targeted at those least inclined to own up to the property of their home and mind?

Falling Fortunes

So what of the distressed poet and enraged musician: Might their consciences be caught by the painter in a silent play-within-a-play? When the enraged musician was described by an early critic as a master of heavenly harmony, it was added that to the evils of poverty he is now a stranger. But if now a stranger, presumably he wasn’t once. This is a most telling detail. The display before his eyes of everything foreign is made into a one-to-one confrontation with his former self. Opening the shutters to stare out in horror, he sees a hell of poverty, the wind player without a curing face or hand. His habit of mind has so fixed him that he cannot face the proverbial truth staring back at him: that fortune, like the stock-market, comes with no guarantee of lasting, and that it ill behooves a person of professions to sit too securely on his Apollonian laurels. The fear of this enraged musician falling is matched by the distress of the rising poet. Placed into a pattern of youth and age, the painter redistributes the economy of wit with a poetic justice to suggest a poverty in having the wrong thing and a wealth in the having of nothing.

On November 24, 1740, London’s Daily Post announced the publication of the distressed poet and the provoked musician, and that a Third on Painting would soon complete the set, but since its subject may turn upon an affair depending between the right honorable, the Lord Mayor and the author, it may be retarded for some time. No one thereafter specified the affair, although everyone assumed that it concerned something political, religious, or economic. Perhaps the promise was false: a subtle joke. The announcement was recorded for posterity by A Microloger in the 1783 review of John Nichols’s 1782 ‘Original Anecdotes of Hogarth and Illustrations of His Plates,’ published in The Gentleman’s Magazine. The Microloger, in truth George Steevens, wrote that Humphry Parsons was at that time Lord Mayor; but the business alluded to, not being in the city records, must remain obscure until someone who knows more about it than I do shall explain it.

The 1740 announcement is suggestive enough for us to consider that the image was started but not finished; finished but lost; not started at all; or finished in a way contrary to expectation. Most who speculate on the missing third painting surmise that Hogarth would have drawn the mood from Johnson’s poem London: Where once the harass’d Briton found Repose, And safe in Poverty defy’d his Foes. But which mood – a painter harassed, defiant, or in repose? My own suggestion is that the painter would have stood back to reflect on all the moods. Consider that having finished his Enraged Musician and Distrest Poet, Hogarth felt the full force of his satire of professions. Exhausted, he was not inclined to subject the painter to the same – knowing anyway that any image from his hand would be read as a self-portrait. What then to do: paint a happy painter? Or do nothing, knowing that, with every issue from his hand, he had already given away in telling details little pieces of his self? With no painting of the painter, did Hogarth not prove himself victorious in every battle for which he had drawn the battle lines over the landscape of social satire? Was not every one of his pictures an implicit portrait of a painter back-to-face with viewers and critics? Were there a picture to title, I would suggest The Embattled Painter for the painter who wryly smiles knowing that he cannot lose.

In 1745, Hogarth painted himself. Was this the unacknowledged third picture? He looks well fed and clad in a red coat, with ample tools for the making of his art ready to hand. Neatly stacked books by Shakespeare, Milton, and Swift are visible, in front of which sits an adoring pug-dog seemingly always ready to listen to his master’s voice. However, with the S-lined palette, this picture twisted a shaggy tail. For why paint himself as an Old Master painter in an Old Master painting and not as a modern engraver or printmaker? Was he aspiring to something he claimed to be against? Or was he mocking connoisseurs who expected self-portraits to look only like this? An X-ray reveals that Hogarth clothed himself first more formally and as out of date before opting for a more ambiguous dress. Many then note the final mockery in the micrology: the slight smile in the face; the painter sculptured as a dead bust on a table of still-life objects; the oversized dog. The micrology is all: Every detail is telling in every nook and cranny of this subtly reinvented picture plane.

But his later self-portrait in print suggests even more. It shows Hogarth sitting before this easel, drafting the antique muse of comedy. Begun in 1758 and reworked up to his death in 1764, it at first showed something obvious: a dog pissing on Old Master paintings. Hogarth deleted the dog, better to display his capability of industry without visual interruption. Leaning on the easel are books possibly about comedy, but there is no other furniture. Hogarth knew how to read these books and which books to read, as his distressed poet apparently did not. Even more, he uncrowded this late picture maybe to show that he alone, with nothing by way of everyday things, could (re)produce everything. The absence of furniture is mirrored in the outline of the painting, the sense that its colors, not yet there, are not needed, either because the painter has his ideal in mind or, better, because this painter knows how to give his life to etching even in black and white. In the painted version, the books are omitted altogether.

If, nevertheless, there is any residue of anxiety, it may be due to the memory of his being caricatured in youth by the academy of portrait painters who were painting successfully in the French, Italian, or Dutch style. Already around 1737, a cartoon attributed to Moses Vanderbank showed a distressed poet looking very like Hogarth sitting at his desk with hand on distressed brow as the bailiffs demand payment: A Noted Bard Writing a Poem in Blank Verse to lay before Sr. R – on the great Necessity at this time for an Act of INSOLVENCY. If then, with The Distrest Poet, Hogarth produced an oblique self-portrait of himself in youth, might we read The Enraged Musician as expressing his fear of becoming in age a portraitist by the book, quite as conventional as the elders self-satisfied to mock him in his youth?

Hogarth rendered the need for a third picture redundant. Everything he put into his enraged musician and distressed poet showed his hand at social satire. Everything foreign was brought home to spread the moods across the entire social situation of painting as a profession. The absent painting is present as unseen in every one of his pictures, a self-portraiture for a self that is carried by all the faces. Reinventing the picture plane, he turned the laughter to tears by showing musicians and poets doing nothing, as relying too much on the promise of divine inspiration, leaving as a result everyone else to make the world. To paint a painter not doing anything was more than a contradiction in terms: It was the final condemnation. Hogarth’s first self-portrait showed a past master with a dormant palette; his final self-portrait showed the touch of his hand in the living brush. Looking at what is on display in Hogarth’s satire only for its face value is to stop the ears from listening to what the pictures say. What is missing was there all along.