Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Contents

- Ancient Mathematics

- Foreword

- Sherlock Holmes in Babylon

- Words and Pictures: New Light on Plimpton 322

- Mathematics, 600 B.C.–600 A.D.

- Diophantus of Alexandria

- Hypatia of Alexandria

- Hypatia and Her Mathematics

- The Evolution of Mathematics in Ancient China

- Liu Hui and the First Golden Age of Chinese Mathematics

- Number Systems of the North American Indians

- The Number System of the Mayas

- Before The Conquest

- Afterword

- Medieval and Renaissance Mathematics

- The Seventeenth Century

- The Eighteenth Century

- Index

- About the Editors

Hypatia and Her Mathematics

from Ancient Mathematics

- Frontmatter

- Introduction

- Contents

- Ancient Mathematics

- Foreword

- Sherlock Holmes in Babylon

- Words and Pictures: New Light on Plimpton 322

- Mathematics, 600 B.C.–600 A.D.

- Diophantus of Alexandria

- Hypatia of Alexandria

- Hypatia and Her Mathematics

- The Evolution of Mathematics in Ancient China

- Liu Hui and the First Golden Age of Chinese Mathematics

- Number Systems of the North American Indians

- The Number System of the Mayas

- Before The Conquest

- Afterword

- Medieval and Renaissance Mathematics

- The Seventeenth Century

- The Eighteenth Century

- Index

- About the Editors

Summary

Introduction

The first woman mathematician of whom we have reasonably secure and detailed knowledge is Hypatia of Alexandria. Although there is a considerable amount of material available about her, very much of that is fanciful, tendentious, unreferenced or plain wrong. These limitations are to be found even in works that we might hope to be authoritative; for example, the entry in the Dictionary of Scientific Biography (DSB) [11]. Even where the account given is more careful and accurate [14, 19, 20], one is disappointed to be told so little of Hypatia's Mathematics.

This article will direct the reader's attention to the best accessible sources and will describe what is known about her mathematical activities.

The historical background

In about 330 B.C., Alexander the Great conquered northern Egypt and, via a deputy (Ptolemy I Soter), founded a city (Alexandria) in the Nile delta. This almost immediately became home to the Alexandrian Museum, an institution of higher learning, rather akin to the medieval universities of some 1500 years later. Euclid was an early (probably the first) “professor” of mathematics.

The Museum continued for many centuries. In 30 B.C., Cleopatra's suicide allowed the Roman Empire to occupy Alexandria, but this event destroyed neither the city's Greek heritage nor its intellectual tradition. In the years that followed, two of the greatest of the late Greek mathematicians flourished in Alexandria. Diophantus was active around A.D. 250 and produced in particular his Arithmetica at this time. Several generations later, Pappus (c. 300–c. 350) also worked there.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

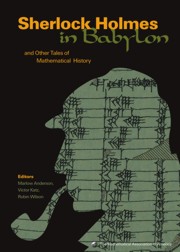

- Sherlock Holmes in BabylonAnd Other Tales of Mathematical History, pp. 52 - 59Publisher: Mathematical Association of AmericaPrint publication year: 2003