Introduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 October 2023

Summary

The Bloomsbury Group historian S. P. Rosenbaum commented in 2007 that Clive Bell's reputation had long been underestimated, noting how influential was his first book, Art (1914), and calling it the ‘first of Bloomsbury's manifestos’ (217). My biography, Clive Bell and the Making of Modernism (2021), has gone some way to establishing how significant Bell was in the early twentieth century both as an art critic and as an outspoken defender of the values of individual liberty. Rosenbaum lamented that not only was there no collected edition of Bell's writings but also no volume of his ‘lively correspondence’ (ibid.). Having relied heavily on that correspondence to write Bell's biography, I knew that he was, indeed, a lively, witty, opinionated and usually very well-informed letter writer. At a private view of Vanessa Bell's 1934 solo exhibition at Lefevre, for example, Clive observed Margot Asquith cautioning his wife against ‘hot backgrounds’ in her paintings – ‘backgrounds should always be grey, my Dear’. On the same occasion, when the somewhat deaf Ethel Smyth was introduced to Charles Laughton, she asked him his name, telling the famous actor that he looked ‘uncommonly like Charles Laughton’ (27). The absurdities of life in situations serious and trivial often struck Bell. During the First World War, he wrote sarcastically to the New Statesman that the government should invest in establishing private bullrings to breed draught animals for the Front, and to amuse the upper classes. After all, he said, it had been agreed already that ‘Art, literature, science, education – all the things that don't really matter – must go’ (68). His letters afford us glimpses of the famous – James Joyce in Paris in 1921 – and the not-yet famous – Ian Fleming in Venice in 1931 – observed in Bell's sometimes acerbic, often insouciant and usually entertaining style.

After making this selection from Bell's letters, I decided to arrange them in eight categories to provide a sharper view of his varied interests and passions than would emerge from a strictly chronological sequence. Although this results in returning to the early twentieth century at the start of each section, the arrangement affords a more coherent perspective than strict chronology would allow, enabling us to see how Bell's thinking might change on a particular subject (politics, for example), or how it remained the same: his belief that war can only ever make the world worse than it is never budged.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

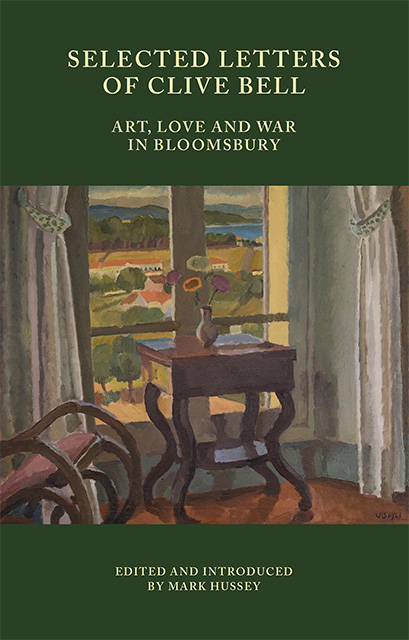

- Selected Letters of Clive BellArt, Love and War in Bloomsbury, pp. 1 - 3Publisher: Edinburgh University PressPrint publication year: 2023