Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: ‘Representation’ and Medieval Mediations of Violence

- Part I The Ethics and Aesthetics of Depicting War and Violence

- 1 Medieval Warfare – Representation Then and Now

- 2 Depicting Defeat in the Grandes Chroniques de France

- 3 Visualising War: the Aesthetics of Violence in the Alliterative Morte Arthure

- Part II Debating and Narrating Violence

- Part III Experiencing, Representing and Remembering Violence

- Bibliography

- Index

2 - Depicting Defeat in the Grandes Chroniques de France

from Part I - The Ethics and Aesthetics of Depicting War and Violence

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 September 2016

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- Introduction: ‘Representation’ and Medieval Mediations of Violence

- Part I The Ethics and Aesthetics of Depicting War and Violence

- 1 Medieval Warfare – Representation Then and Now

- 2 Depicting Defeat in the Grandes Chroniques de France

- 3 Visualising War: the Aesthetics of Violence in the Alliterative Morte Arthure

- Part II Debating and Narrating Violence

- Part III Experiencing, Representing and Remembering Violence

- Bibliography

- Index

Summary

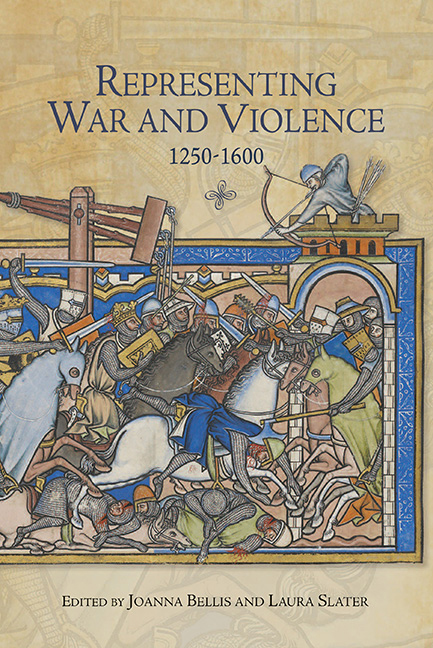

In 1302 the heavy cavalry of France, pre-eminent symbol of its aristocratic power, fell before the foot soldiers of Flanders at the Battle of Courtrai. Throughout the following century, both chroniclers and artists devised numerous strategies for representing this startling upset of conventional military logic. The challenging nature of this task is evident in the text and miniatures of the Battle of Courtrai found in two manuscripts of the Grandes Chroniques de France created for the French kings Charles V (r. 1364–80) and Charles VI (r. 1380–1422): Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale MS français 2813 (hereafter BnF 2813) [Plate 1], and Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale MS français 2608 (hereafter BnF 2608) [Plate 2]. While the two manuscripts’ texts are identical, their visualisations of Courtrai diverge in startling ways. In BnF 2813, the French knights seem destined to defeat their ill-equipped enemies. BnF 2608 instead shows the French in chaotic retreat from a menacing force of armoured foot soldiers, who cut down the few remaining knights at the centre amid a sea of broken bodies. In both cases, the artists embroidered on tensions already existing in their shared accompanying text even as they diverged from it. While the earlier miniature rewrote history to aggrandise French royal power, the second version likewise deviated from the textual account to exaggerate the horror and shame of defeat. Taken together, the text and images used to make the defeat at Courtrai intelligible in the Grandes Chroniques suggest the continued ambiguity of past battles and the multiple roles that their representations could play, even in closely related manuscripts originally located within a single library.

In what follows, I will first provide a basic outline of the Battle of Courtrai to provide a baseline for analysis of its later reinterpretations. I then turn to its evolving textual representations, with special attention to the historiographical tradition of the Abbey of Saint Denis that formed the Grandes Chroniques’ text. Unlike most contemporary chroniclers, the Latin Chronicon of William of Nangis and its expanded French translation in the Grandes Chroniques avoided characterising the French and Flemish using simple binaries such as good/evil, model/ anti-model, ally/enemy. Their complex verbal accounts of Courtrai set the stage for the divergent visual representations made for Charles V and Charles VI at the end of the century.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Representing War and Violence, 1250-1600 , pp. 39 - 55Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2016