Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Subjectivity in Troubadour Poetry

- Part II The ‘Chansons de geste’ in the Age of Romance: Political Fictions

- Part III Courtly Contradictions: The Emergence of the Literary Object in the Twelfth Century

- Part IV The Place of Thought: The Complexity of One in French Didactic Literature

- Part V Parrots and Nightingales: Troubadour Quotations and the Development of European Poetry

- Part VI Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries

- Afterword

- General Bibliography

- List of Manuscripts

- Bibliography of Work by Sarah Kay

- Index

- Gallica

Sheep, Elephants, and Marco Polo’s Devisement du monde

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 May 2021

- Frontmatter

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- List of Contributors

- List of Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I Subjectivity in Troubadour Poetry

- Part II The ‘Chansons de geste’ in the Age of Romance: Political Fictions

- Part III Courtly Contradictions: The Emergence of the Literary Object in the Twelfth Century

- Part IV The Place of Thought: The Complexity of One in French Didactic Literature

- Part V Parrots and Nightingales: Troubadour Quotations and the Development of European Poetry

- Part VI Animal Skins and the Reading Self in Medieval Latin and French Bestiaries

- Afterword

- General Bibliography

- List of Manuscripts

- Bibliography of Work by Sarah Kay

- Index

- Gallica

Summary

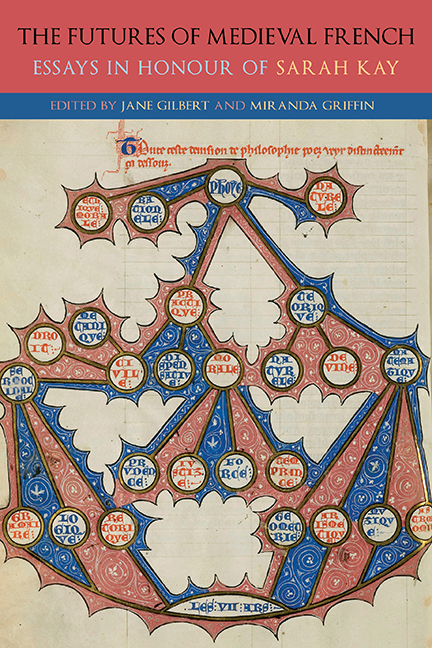

IN ANIMAL SKINS, Sarah Kay explores the consequences of the fact that the manuscripts transmitting the texts we read and study were composed of animal skins; the parchment page, she writes, is ‘the site of convergence between seeming incompatibles: between bare life and intellectual life, livestock and literacy, the history of the book and the seemingly ahistorical existence of nonhuman animals’ (2). Having begun with sheep as providing the very material from which medieval manuscripts were made, the book concludes with elephants – focusing on an image, reproduced on the book's dust jacket, from Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS fr. 14969 (fol. 60r), a late thirteenth-century English Franciscan manuscript of the vernacular French bestiary of Guillaume le Clerc. Like encyclopaedias and universal histories, bestiaries seem to lay claim to a kind of fixed and authoritative knowledge. Kay's analyses, however, reveal how unstable the ‘textual identities’ of bestiary animals are across traditions (8). In this essay, I take Kay's study of bestiaries as the point of departure for a different kind of enquiry: how textual representations of sheep and elephants, the two creatures that bookend Animal Skins, mediate boundaries between different medieval cultures (see Kinoshita 2012). As a matrix for this exploration of the Global Middle Ages, I take Marco Polo's Devisement du monde (1298), which, as Simon Gaunt (2013b) has shown, insistently thematises diversity of various kinds. For our purposes, sheep and elephants – exemplifying the utterly domestic and the utterly exotic, respectively – not only prove good to think with, they allow us a window onto the diversity, zoological and cultural, of animals across a range of texts, genres, and traditions. Where Kay brings out the implications of the materiality of the manuscript page, Marco shows us the material existence of the animals themselves – how they matter to humans not as allegorisations, codified by repetition, based upon a presumed set of behaviours, but by their embeddedness in the various, often interconnected cultures spanning medieval Eurasia.

Sheep in the Latin West

Sheep, as Kay notes, are relative latecomers to the bestiary tradition. Sheep come (literally) into the picture in the Latin ‘Second Family’ bestiaries that first appear in mid-twelfth-century England, which introduced new chapters – including one on Sheep (SF §33) – just after the chapter on Adam (Animal Skins: 27).

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Futures of Medieval FrenchEssays in Honour of Sarah Kay, pp. 314 - 328Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021