Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Tribute to Professor Bhekizizwe Peterson

- Introduction

- Part I Remapping and Rereading African Literature and Cultural Production

- Part II South Africa and Fugitive Imaginaries

- Part III In the Eye of the Short Century: Diaspora and Pan-Africanism Reconsidered

- Contributors

- Index

2 - Foundational African Literary Discourse and Dimensions of Authority

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 September 2022

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Tribute to Professor Bhekizizwe Peterson

- Introduction

- Part I Remapping and Rereading African Literature and Cultural Production

- Part II South Africa and Fugitive Imaginaries

- Part III In the Eye of the Short Century: Diaspora and Pan-Africanism Reconsidered

- Contributors

- Index

Summary

Modern African literature has what some may describe as ambiguous beginnings or origins. Ambiguous in the sense of the various regional or subcontinental impulses that compelled its modern existence. Its foundation within the context of modernity itself is as complex, and as charged, as any attempts to give a single meaning, or definition, to ‘modernity’ as an aesthetic or philosophical concept. Literary historians and critics often date modern African literature from the publication of Thomas Mofolo’s historical novel, Chaka, first written in Sesotho, or even Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi. So then would we consider Pita Nwana’s Omenuko or Daniel O. Fagunwa’s Ògbójú Ọdẹ nínú Igbó Irúnmọlẹ̀ (The Forest of a Thousand Daemons), both of which were novels written in indigenous languages? There was Amos Tutuola’s The Palm-Wine Drinkard, and Cyprian Ekwensi’s novel People of the City. These novels do unquestionably constitute an African canon, and their situation often raises questions about the foundations of African literary modernity and praxis. More so as many critics also connect the momentous publication of Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart in 1958 with the emergence of the modern African novel. The currency of this dating may well have to do with the significance of that moment: the decolonising process was coming finally to a head with the rise of the new, modern African nation states after the colonial encounter.

African independence signified a novelty that in itself brought with it the myth of rebirth and renewal. Achebe’s novel very clearly benefited from that mood, born at ‘the brink of such great events’, as the poet Christopher Okigbo would say. A novel like Things Fall Apart set things in sharp relief; it situated in a sense the stirred spirits of the new age, and of the new nations, not only as a moment of political and spiritual awakening, but as a form of ritual itself, through which invocations are made. For that awakening to be fully meaningful, Achebe himself said − and he put this in the mouth of another memorable character, the high priest Ezeulu, in his second novel, Arrow of God − we needed to know ‘where the rain began to beat us’.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

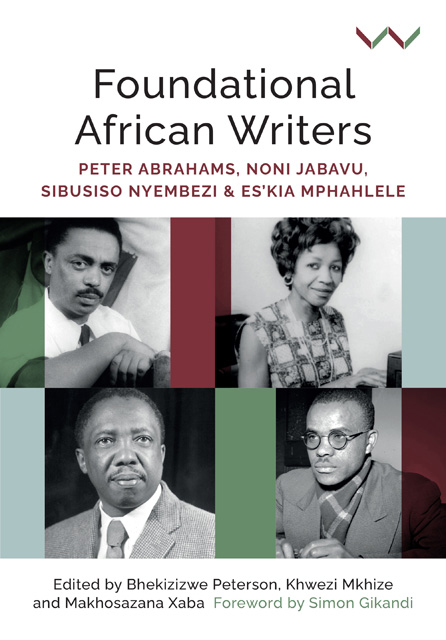

- Foundational African WritersPeter Abrahams, Noni Jabavu, Sibusiso Nyembezi and Es'kia Mphahlele, pp. 53 - 74Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2022