The palaeography of twelfth-century manuscripts is defined by transformation. Book scripts used by European scribes show considerable change over the course of the century, whereby either a substantial number of letterforms or an entire script system was replaced. For example, Visigothic disappeared over the course of the twelfth century, while Beneventan shifted into a period of decline from around 1200, the first signs of which are already observed in the twelfth century.1 An important factor in these shifts is the emergence of Gothic script, or rather, the coming of features that would ultimately culminate in the script we call Gothic Textualis.2 For example, what Lowe identifies as markers of decline in Beneventan are, in fact, Gothic traits that become woven into the script, including key features such as the angular appearance of round strokes (‘angularity’) and biting in adjacent letters with contrary curved strokes (‘biting’), which Lowe calls ‘unions’.3 However, rather than focusing on geographically confined ‘national’ styles of handwriting, this chapter assesses the scripts used for books across Europe in general. Ultimately this undertaking brings to the foreground one particular kind of script, Caroline minuscule, albeit that the twelfth-century version looks quite different from what is encountered in the Carolingian age. The challenge of this chapter is to assess how and to what extent twelfth-century script deviates from ‘pure’ Caroline minuscule, how the influx of new features occurred over time and whether something can be said about the geographical spread of these novelties.

Caroline, Gothic and Pregothic

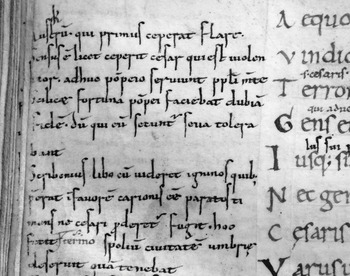

As in many other respects, the twelfth century is a transitional period from a palaeographical point of view. As the period progresses, we witness the waning of Caroline minuscule, the dominant book script from ca. 800 to ca. 1100, as well as the proliferation of letterforms that are usually regarded as features of Gothic Textualis, a script whose life spans from the early thirteenth to the sixteenth century. While there is considerable agreement about what constitutes Caroline minuscule and Gothic Textualis, whose traits are fairly well defined,4 palaeographers show less conformity about the script encountered in the twelfth century, a script that shows a mixture of Caroline and Gothic features (Figure 2.1). Some define this style of handwriting as a late expression of Caroline minuscule, addressing it with such terms as ‘Late Caroline’ or ‘Post Caroline’, while others regard it as an early form of Gothic Textualis, labelling it ‘Primitive Gothic’, ‘Proto-Gothic’, ‘Littera praegothica’ or ‘Pregothic’. Emphasizing the script’s hybridity, a third group calls it ‘Carolino-Gothica’, ‘Caroline gothicisante’, ‘Minuscola di transizione’, ‘Übergangsschrift’ or ‘Transitional script’.5

Figure 2.1 Pregothic book script, dated 1145–9. Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, BPL 196.

There is also disparity with respect to the start and longevity of this ‘Pregothic script’, as it is addressed here for convenience. While most palaeographical handbooks place the start in the late eleventh or early twelfth century, the verdict of when the script reaches maturity varies from the late twelfth century to ca. 1275,6 which may be reflective of the geographical variation in the adoption of the script, as is discussed later in this chapter. In the same handbooks Pregothic is treated as an entity of its own, meaning that it is discussed in a separate chapter or section. There are reasons not to do so. Both Caroline and Gothic are stable script systems with core features that remained unchanged even as regional peculiarities emerged. In contrast, Pregothic script is, at its heart, defined by continuous change, given that it represents a moving point on the sliding scale from Caroline to Gothic. Starting in the eleventh century, the script develops from an almost pure form of Caroline minuscule with a modest number of features we tend to define as Gothic to, in the thirteenth century, a script that can almost be called Gothic Textualis, were it not for some remaining traces of Caroline. By definition Pregothic script is never Caroline or Gothic, but it represents a collection of stages in between the two script systems.

This blend makes Pregothic problematic to define, study and understand. A major problem is that of identity. It is unclear when Caroline minuscule has acquired sufficient change to be called something else: how many Gothic features does a Caroline bookhand need to take on before it can be called Pregothic? The variety of terms used to address the transitional script of the Long Twelfth Century is telling of just how differently scholars are inclined to answer this query. Some observations in this chapter further aggravate this problem, in particular that some of the features defined as ‘Gothic’ in palaeographical handbooks are in fact encountered as early as the second quarter of the eleventh century. A second problem is that of description. While Pregothic is evidently a different beast from the scripts that flank it, we have no vocabulary at our disposal to explain precisely in what way. Because Pregothic script is Caroline minuscule that includes, to a varying extent, Gothic features, one is forced to describe Pregothic by referring to features of two other scripts. There are, at any rate, no apparent script features that are unique to Pregothic in that they were not included in Caroline or would not become part of Gothic.

Assessing Pregothic Book Script

Given that the presence of Gothic features is ultimately what differentiates Pregothic from Caroline, a way out of the first problem – when to call a style of handwriting Pregothic – may be to focus on the emergence and development of Gothic traits, as is done in this chapter. In an attempt to define Pregothic and assess its development, this chapter drafts into service all dated and datable manuscripts contained in the Catalogue des manuscrits datés that were produced between 1075 and 1225, a total of 353 manuscripts. For each of these, twenty-eight palaeographical changes are examined and keyed into a database, noting whether a letter shape’s execution is in Caroline or Gothic style, or whether a manuscript features both forms at the same time (a mixed use of traditional and new forms).7 This quantitative approach ultimately shows how the execution of letterforms changed over time, allowing us to measure the waning of Caroline, the emergence and attainment of Gothic features, the speed of their adoption and the regional variety in their application. Before turning to these key issues, the second problem – that of description – needs to be addressed. How does one describe evolving letter shapes in such a way that they can become part of quantitative research?

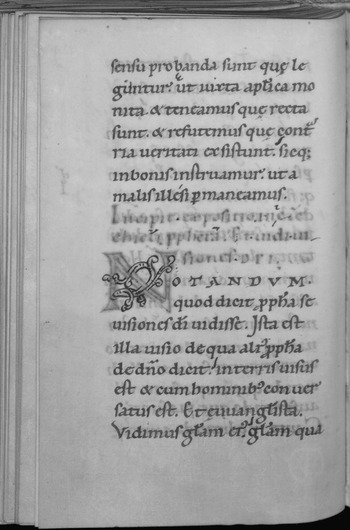

The answer to this question lies in a particular mode of change encountered in the developing script of the twelfth century. As I argue elsewhere in more detail, medieval scribes in the process of adopting a new script changed their scribal mannerisms in two ways.8 The first is through a process that may be called ‘substitution’, whereby one graph (letterform) was replaced by another. Pregothic script encompasses only a modest number of these: the introduction of two uncial letterforms (round d and s) and the emergence of the orum abbreviation for r (‘round r’).9 These new forms were introduced relatively late in the period and they gained ground very slowly (Figure 2.2). For example, the oldest dated manuscripts in which d and s are consistently presented in uncial form were made in 1125–49.10 At the close of the Long Twelfth Century, in 1200–24, less than half of the manuscripts consistently present the new forms (d: 37 per cent, s: 19 per cent). Round r, which was exclusively used in or-ligature, gained a much firmer foothold: in the last quarter of our period it is used in 64 per cent of manuscripts.11

Figure 2.2 Three examples of substituting letterforms.

A second mode of change, which can be called ‘modification’, was less invasive and much more common. With modification, a graph was not replaced by something entirely new, but the existing appearance was altered, usually modestly. As in other medieval scripts, it concerned alterations on the level of the stroke, the individual trace of the pen. Such modifications were produced through a change in the stroke’s length (a reduction in some cases, an extension in others), direction (the ‘vanishing point’ of the pen, which can be quantified by comparing it to the dial of a clock) and shape (e.g. straight, curved or forming a bowl). Additionally, scribes modified the number of strokes that were used to produce a graph: either strokes were added to the Caroline presentation of a letter or they were cut.12 This second mode of change is crucial for this chapter, because the notions of ‘reduction’, ‘extension’, ‘direction’ and ‘number’ enable us to assess the hybrid script of the Long Twelfth Century in a quantifiable manner. Approaching Pregothic script in this fashion offers three important insights, which are addressed in the remainder of this chapter: script development in the twelfth century lacks cohesion, is much less innovative than traditionally assumed and shows great regional variety.

Lack of Cohesion

The adoption rate of Gothic features over the course of the twelfth century was uneven. One might perhaps have expected that a distinct form of Pregothic emerged in the handwriting of a small number of scribes, such as inhabitants of a certain intellectual centre or monks affiliated to a certain order, after which that specific style gained popularity among a growing number of scribes and geographical locations. However, the pattern of development is very different. Notably, at a moment when a sharp increase is seen in the adoption of one Gothic letterform, the popularity of another increased only modestly or not at all. For example, at one point the application of Gothic feet (which turn to the right) gains popularity with surprising speed: in 1090–1104 only 20 per cent of manuscripts show this feature systematically, while in 1105–19 the feature has jumped to 70 per cent.13 Typically, however, Gothic features show very little growth in these two decades.

The sharp increase in both the adoption of angularity and Gothic feet draws attention to something else. The two sharp increases occur in the same manuscripts: fifteen of the seventeen manuscripts with consistent Gothic feet also feature angularity. This suggests that a significant number of scribes adopted two particular Gothic features in a short period of time, while not showing interest in a great deal of other new traits. Notably, the adoption of several new features by the same scribe is not a common occurrence in the twelfth century and certainly not for a large group of palaeographical shifts. It is only in the early thirteenth century that it became common for scribes to adopt new Gothic features in larger numbers.

The varying speed with which new features gained popularity and the varying moments at which their popularity increased attest to a lack of cohesion in the book script of the Long Twelfth Century, the development of which appears uncoordinated and random. Other observations underscore this assessment, such as the occurrence of apparently opposing trends. For example, while one letter development entailed an extension of a stroke (the second leg of h and x will ultimately be placed below baseline), in other cases the same stroke was retracted (f, r and s). Ultimately the development of book script between 1075 and 1225 can perhaps best be understood as a collection of individual developments culminating into a style of writing that no longer underwent significant change, thus marking the birth of Gothic Textualis.

Innovation

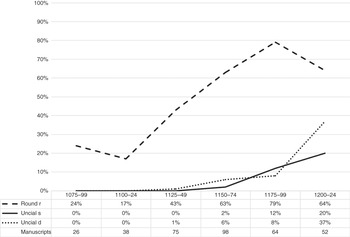

While the chapters in this volume show how the century and a half between 1075 and 1225 represents an age of renewal, it is necessary to temper the traditional verdict that the period is innovative from a palaeographical point of view. The main reason for moderation is the important observation that the roots of many script innovations tied to the twelfth century are, in fact, encountered much earlier. The extent to which Gothic features are present in the last quarter of the eleventh century (when Pregothic script is traditionally regarded as being in its infancy, as discussed) is striking. An example is the Pregothic trend whereby the stem of f, straight r and long s was reduced in size: while Carolingian scribes placed the feet of the stems below baseline, their peers writing Gothic Textualis would ultimately place them on baseline (Figure 2.3). Dated manuscripts suggest that a small portion of scribes in Europe (10 per cent) already placed the f consistently on baseline in 1075–99. More scribes already did so with long s (35 per cent) and straight r (38 per cent). Obviously the beginning of this particular palaeographical trend predates 1075.

Figure 2.3 Examples of increased popularity of placing feet on baseline.

Many other Gothic features appear in such high numbers in the last quarter of the eleventh century. For example, fifteen of the twenty-six dated manuscripts made in that period (71 per cent) extend the second leg of x below baseline (on baseline in Caroline); thirteen (50 per cent) present their a in the Gothic fashion, with the vertical stroke in an upright position (slanted in Caroline); eight manuscripts (31 per cent) present g with a closed lobe (open in Caroline); the same number use uncial d complementary to straight d; in seven manuscripts (27 per cent) the ‘tongue’ stroke of e is traced in the direction of two o’clock on the dial (three o’clock in Caroline); and in four (15 per cent) the minims are in the Gothic style, meaning their feet turn to the right (to the left or down in Caroline). Notably, these examples all concern manuscripts in which a scribe consistently presents a given letter shape in the Gothic style. If we also include cases in which the Gothic presentation is used from time to time in an individual manuscript that also presents these same forms in the Caroline manner, the numbers are even higher. To give one example, in 1075–99 an additional nine manuscripts show a mix of Caroline and Gothic feet at minims, meaning that half of the twenty-six manuscripts from that quarter-century show some degree of ‘Gothicness’ in the formation of their feet (either consistent or sporadic).

These examples highlight a key feature of script development in the twelfth century: many of the palaeographical shifts measured in that century have, in fact, older roots. For a number of script features these grow deep into the eleventh century. For example, the sixty-five dated manuscripts produced between 1000 and 1074 show that the practice of placing the stems of f, r and s on baseline was not uncommon in the second quarter of the century (Figure 2.3). Among the seventeen dated manuscripts from this quarter-century two place long s consistently on baseline, three do so for f and five for straight r. Given the absence of these traits in dated manuscripts from the first quarter, it is tempting to infer that the novelty of placing feet on baseline emerged in the second quarter of the eleventh century.14 Some other Gothic traits appear to be even older. For example, among the twenty-three dated manuscripts from the first quarter of the eleventh century there are four in which the stem of t pricks through the bar consistently, while eight present g with closed lobe.

While the numbers in these examples are still relatively low, they do highlight how features considered typical for Littera Textualis were practised by scribes in the first half of the eleventh century, well before the Gothic or even Pregothic period. In fact, while more scribes in the twelfth century began to favour Gothic traits as the century progressed, only a limited number of features are actually innovations of the century itself. Dated manuscripts suggest that the few real palaeographical novelties are: the five different kinds of biting (involving the letters b, d, h, o and p), the extension of the second i in ij, the use of uncial s in final position and the tailed e (e-caudata) that loses its tail.15

There is another reason why we may need to temper a claim that the twelfth century is an innovative period as far as script is concerned. Dated manuscripts show how the process of adopting Gothic features had by no means been completed by the early thirteenth century. In fact, during the first quarter of the thirteenth century few palaeographical features are consistently executed in the Gothic fashion in all dated manuscripts. Notably, ten Gothic features are encountered in fewer than 50 per cent of the manuscripts in the corpus (which, in the period 1200–24, consists of fifty-two manuscripts): uncial d (45 per cent), biting in ‘de’/’do’ (39 per cent), diacritical ij (38 per cent), biting following p (26 per cent), biting following b (24 per cent), biting following h (19 per cent), uncial s in final position (17 per cent), biting following o (15 per cent), use of round r after b or p (13 per cent), ct-ligature (9 per cent) and diacritical single i (7 per cent). In other words, the script developments occurring over the course of the twelfth century do not culminate in a script that has finished developing. It appears that, palaeographically speaking, the period is part of a much longer continuum, as is also suggested by the presence of Gothic features in the first half of the twelfth century.

Regional Variety

Dated manuscripts also highlight, lastly, a lack of cohesion in the geographical spread of Gothic features, which varied significantly in terms of both speed and execution (the manner in which the letters were formed). The extent to which the regional acceptance of Gothic traits varied becomes clear when we compare England, France and the Germanic countries (nowadays Austria, Germany, The Netherlands and Switzerland, and perhaps Flanders as well), which formed a separate Kulturraum.16 The general trend is that during the twelfth century far fewer Germanic scribes favoured Gothic traits in comparison to their peers in England and France. The placement of f, s and r on baseline may serve as an example: this trend is much less popular among Germanic scribes. In most quarter-centuries more than twice as many scribes in England and France execute their r in the Gothic fashion than do their counterparts in Germanic countries.17

Another regional peculiarity of Germanic countries is that some Gothic features are never used there, even when they are well established elsewhere. This phenomenon is witnessed most clearly in fusion or ‘biting’, an important Gothic feature whereby two adjacent contrary curved letterforms started to overlap.18 The feature whereby uncial d consistently merges with round letterforms in an adjacent position (‘de’, ‘do’) first appears in 1150–74 in England and France, albeit in a very low number of manuscripts (4 per cent of surviving dated manuscripts). From there it grows in popularity to 13 per cent (England) and 12 per cent (France) in 1175–99, and subsequently to 60 per cent (England) and 30 per cent (France) at the end of our period, in 1200–24. Notably, this particular type of fusion is encountered in none of the dated manuscripts from Germanic countries in these same periods. The same goes for fusion involving h (‘he’, ‘ho’), o (‘od’, ‘oe’, ‘oq’) and p (‘pe’, ‘po’). Scribes in England and France, in contrast, did use these forms, although not all of them did so in significant numbers. In the last quarter-century of our period relatively few cases of biting involving h are observed (France: 17 per cent, England: 13 per cent), as are those involving o (France: 15 per cent, England: 7 per cent). More frequent is fusion with the letter p (France: 22 per cent and England: 31 per cent). Here the contrast with the mannerism of Germanic scribes, who do not fuse letters with p at all, is most profound.

Observations like these underscore the importance of studying script in the Long Twelfth Century on a regional as well as a broader European level. Moreover, they also identify regional differences as yet another variable in the development of book script – that is, in addition to the precise moment at which Gothic features were introduced and the speed with which they became more popular. Within these large geographical spaces smaller regions may be identified with their own palaeographical peculiarities (e.g. southern France versus France as a whole).19 Within such smaller regions two kinds of palaeographical idiosyncrasies are observed. The first is related to the adoption of Gothic features, and it reflects the pattern witnessed on a supra-regional level: a Gothic feature may be introduced at a different moment or develop at a different speed. For example, scribes in southern France tended not to execute the feet at the minims of m and n in the Gothic fashion (with sharp flicks to the right), but commonly directed them straight down. This happened as late as the second half of the twelfth century, when even the majority of Germanic scribes had embraced this feature.20

The second manner in which a smaller geographical space could branch off in a palaeographical respect does not concern the introduction of Gothic features as such, but the manner in which the new features were executed. For example, while scribes in southern France were at par with their peers in other French regions in the adoption of the seven-shaped Tironian note, which first supplemented and later fully replaced the ampersand, they actually shaped this symbol in a uniquely southern French manner: it is characterized by its upright appearance and by its very long and straight horizontal stroke. Similarly, scribes in the region had their own way of shaping, for example a, i, ta and the con-abbreviation.21 These distinct southern features show that confined geographical areas could develop their own ‘brand’ or ‘interpretation’ of Pregothic.

Among all this geographical variation one region appears to stand out in terms of advancement. As the examples given here show, across the board it is France that most frequently comes in first place regarding the introduction moment of new features and their rate of adoption. It is possible, however, to home in on a region within France where Gothic features are encountered notably early and in high numbers: Normandy. For example, Norman scribes are very early adopters of Gothic angularity and the Gothic fashioning of feet.22 There is more evidence for the advanced position of Normandy. It turns out that Norman scribes also take a prominent position at the head of the column when we observe all (twenty-eight) palaeographical traits that underwent change. When we place the dated manuscripts from 1075 to 1099 in the order of the number of features that have consistently been copied in the Gothic fashion, the first four turn out to have been made in Norman houses, while the fifth was produced in Christ Church, Canterbury, a community that included a large contingent of Norman monks.23

Other Modes of Writing

Given the focus of this volume, namely manuscript books and their contents, the script used for documentary texts has so far been excluded from discussion.24 While full manuscripts are not usually copied in documentary script, it deserves a place in this chapter because it was, from time to time, used for copying a segment of a manuscript. Pregothic documentary script is closely related to Pregothic book script.25 Pronounced differences are the high head of a (which could be extended significantly), the extension of ascenders and descenders, the extension of f and long s below baseline, the sharp turning to the left of the feet at f and s (and sometimes p) and the near-formation of loops at the ascender of uncial d and sometimes f, though this curl is never completed into a real loop (true cursive elements, such as connections between letters, are absent in the script). The top of ascenders is sometimes accentuated with a decorative motif, such as a superfluous curl. All of these features are most clearly observed when Pregothic documentary script is written with a thinner and more flexible pen (as was customary for the production of documents). They are also encountered, though less pronounced, in specimens written with the broad nib used for producing books, although the ascender of d and f do not usually curl.26

When used in manuscripts, Pregothic documentary script is mainly employed as a contrast script, although for this purpose scribes in the Long Twelfth Century preferred to use a smaller version of Caroline or Pregothic, which is sometimes, for this purpose, written with a thinner pen than the main text. Documentary script plays a role in the hierarchy of scripts in that it expresses that the text in question is not part of the actual main text but is somehow standing apart from it. Pregothic documentary script was most often used for glosses, both interlinear and in the margin (Figure 2.4),27 although scribes in the Long Twelfth Century clearly preferred a smaller version of Caroline or Pregothic for this purpose. Bischoff therefore called the script in question ‘Glossenschrift’, although others prefer the term ‘notula script’.28 When used for glosses, the script is usually notably smaller than the version used in charters, which probably results from the confined space of the margin and in between two lines.

Figure 2.4 Pregothic documentary script used for added glosses, eleventh century, with twelfth-century marginal and interlinear glosses. Leiden, Universiteitsbibliotheek, VLQ 51.

A larger version was used for adding text within the actual text columns, although this appears to have happened infrequently. In such cases the similarity with Pregothic book script is much more striking than in the minuscule gloss version: the central part of the letters (ascenders and descenders excluded) is effectively the same. This larger version of the documentary script is nearly always used for writing down short texts, such as ex libris inscriptions,29 colophons,30 notes,31 tables of contents,32 short introductions,33 capitula lists,34 calendar or obituary entries,35 enumerations36 or segments of manuscripts.37 Full texts are rare, although there are exceptions, such as the autograph of Nigel Witeker, presumably a draft text, which was written in 1193–4 (Cambridge, Gonville and Caius Coll. 427/427), and a Computus written in England or Wales in 1164–8 (Bodl. Libr. Digby 56). Here scribes resorted to documentary script not so much because of the contrast it provided with the Pregothic book script (which is not even found in the manuscripts), but probably because it provided a faster means to copy the text. The ‘utilitarian’ nature of the works may have invited a less formal writing style because it meant the copying could be done with less effort.

From time to time one encounters a manuscript from the Long Twelfth Century copied in a bookhand that was influenced by Pregothic documentary script. Such influence is often shown by an extension of f and s well below baseline, perhaps even with the foot bending sharply to the left. A notably early example of such influence is a manuscript made in Freising in 1022 (BSB Cgm 5248/7), with extended f and s and decorative curls at the top of ascenders.

Making a Script

The observations presented so far prompt several important queries: What motivated scribes to seek new ways of executing letters? How did Gothic features become established among individual scribes or groups of scribes sharing a scriptorium? How does a palaeographical feature turn from idiosyncrasy into norm? A key notion at the heart of these issues must be training, which is where the acquisition of any script started. While little is known about scribal training, in most monasteries of the eleventh and twelfth centuries there will probably have been a person assigned the task of teaching novices to write. Some have argued that the cantor played this role, given that he was responsible for running the school and supplying scribes with the materials for producing manuscripts.38

Cohen-Mushlin’s study of the scriptorium at Frankenthal in the second half of the twelfth century suggests that students learned to write a script by studying writing samples of their master and attempting to imitate his style. This was done, she states, to ensure the production of palaeographically ‘homogenous and uniform manuscripts’.39 Surviving Frankenthal manuscripts show how this was achieved. First the master wrote out a few lines, after which the student took over and wrote a few lines of his own. Then the master took over again, writing a few lines, after which the pupil wrote some more.40 ‘Taming’ pupils in this fashion (as Cohen-Mushlin calls it) – which implies that master and student actually sat next to one another – may have been a much broader practice. It is also encountered, for example, in manuscripts copied by Orderic Vitalis (d. 1142) in the Norman house of St-Évroult.41

The teaching method whereby the teacher’s handwriting is used as a model and where the teacher closely monitors how well the student is following his example demonstrates the importance of the monastic writing master to the process of script change, at least within individual communities. After all, a conservative teacher could arguably hold back, palaeographically speaking, several generations of new monks in his vicinity, while one who was willing to weave new letterforms in his script had the ability to advance script around him. Particularly important is how closely the script of the pupil could match that of his teacher, which is evidenced both by the manuscripts from Frankenthal and by those produced by Orderic Vitalis. In fact, in books from St-Évroult a hand is encountered that looks so similar to Orderic’s style of writing that the writer is dubbed his alter ego. Chibnall concluded that the scribe ‘had learnt to write under [Orderic’s] guidance, and had modeled himself remarkably closely to his master’.42 Such observations suggest that if the writing master included Gothic features, these subsequently had a good chance of spreading through the community.

Still, training cannot be the whole story. The history of Pregothic script is one of continuous – if inconsistent – change, which could only have occurred if monastic writing masters were introduced to new script features on a regular basis. In other words, another key notion in the development of book script in the Long Twelfth Century must be travel, either by members of religious houses or by their books. The Norman Conquest shows just how profound the influence of travelling mannerisms could be on the development of a book script. Norman scribes, whose handwriting was heavy on Gothic traits, spread an advanced form of Pregothic script throughout England as they entered religious communities there.43 This may help explain why the scripts of England and France take a similar path of development in the late eleventh and early twelfth centuries, as the figures shown earlier suggest. Moreover, the scripts include palaeographical traits not seen elsewhere in Europe, such as the macron in the shape of a bowl that is slightly slanted.

In the wake of the Conquest two houses in Kent adopted a writing style that was modelled on script from the Norman abbey of Bec. The script, which is known as ‘prickly’ because of the split tops of ascenders, the use of hairlines and the pointy top or back of round letters (c, e, o, t), was first developed in Christ Church, Canterbury and then brought to Rochester, where it was used in its own distinctive style.44 Rochester monks all came from Normandy, but some were trained in other Continental regions, such as Germany, the Low Countries and Italy. In the first quarter of the twelfth century, they all abandoned their native styles and switched to the new prickly script, which may have been modelled on the handwriting of Ralph, the community’s prior until 1107, whose manuscripts are early and pronounced examples of prickly script.45 The new script was executed so perfectly within the community that the Continental origins of their users became hidden: only when the scribes tested their pens on flyleaves did they reveal their native script, as if lowering their guard for a few moments.46

The case of Rochester not only underscores the importance of modelling and travel but also how an entire community could quickly and perfectly switch palaeographical register and acquire a new script that was heavy on Gothic traits. Given these observations, the lack of speed and consistency in the development of book script during the twelfth century in general is all the more striking: if individual communities and regions could adopt Gothic features so quickly and consistently, why does the Europe-wide process of adoption lack speed and uniformity?