Book contents

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Economics

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Economics

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I Histories and Critical Traditions

- Part II Contemporary Critical Perspectives

- Part III Interdisciplinary Exchanges

- Further Reading

- Index

- Cambridge Companions To …

- References

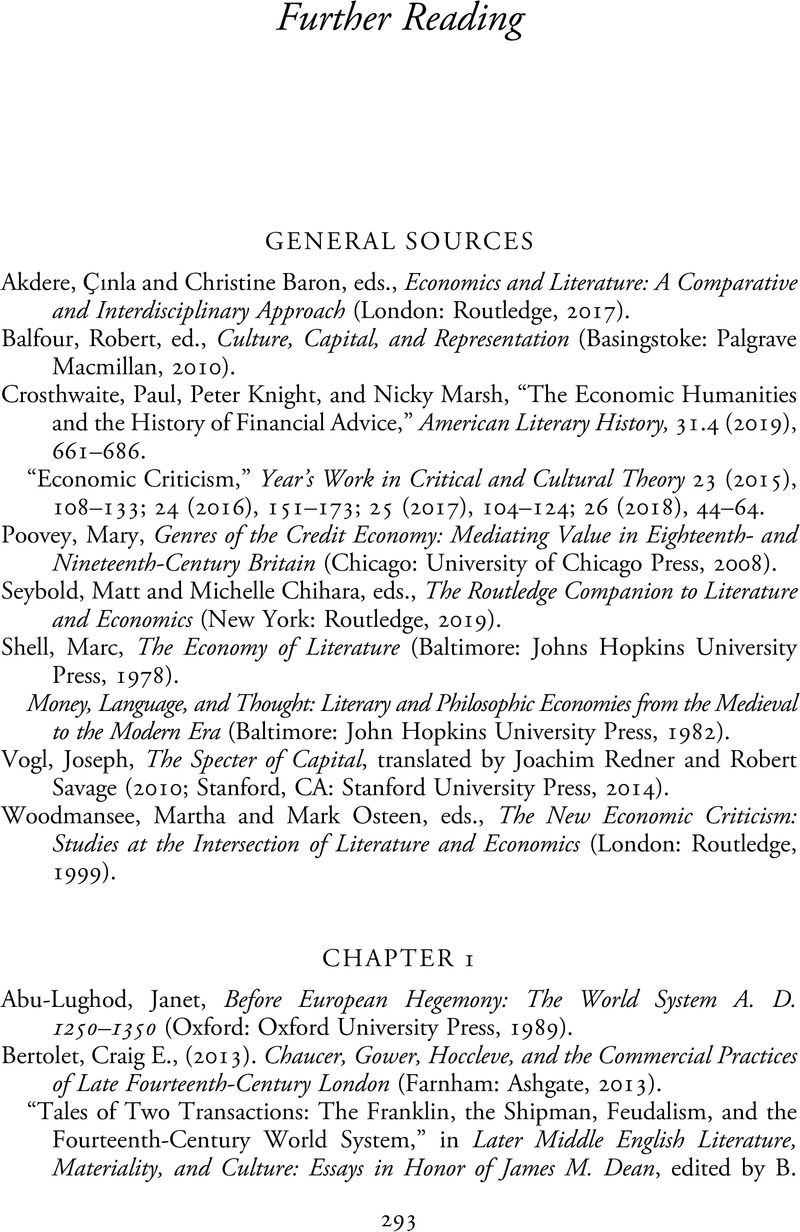

Further Reading

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 28 July 2022

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Economics

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Economics

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Contributors

- Introduction

- Part I Histories and Critical Traditions

- Part II Contemporary Critical Perspectives

- Part III Interdisciplinary Exchanges

- Further Reading

- Index

- Cambridge Companions To …

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- The Cambridge Companion to Literature and Economics , pp. 293 - 305Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2022