2 The Land of Aššur in the Late Bronze Age

Introduction

The starting point for this investigation is the discovery of a number of collections of cuneiform tablets left behind by the Assyrians at different places in the centuries from about 1400 to 1000 BC. This is conventionally referred to as the Middle Assyrian period, falling as it does between the Old Assyrian (roughly 2000–1500 BC) and the Neo-Assyrian (roughly 1000–600 BC) periods. These terms are used by philologists to refer to phases in the development of the Assyrian dialect of Akkadian, but they also correspond broadly to different stages in the existence of an Assyrian state, originating at the city of Aššur on the west bank of the Tigris, and governed from there throughout the second millennium BC, although in the first millennium the effective seat of government was transferred northwards, first to Kalḫu, subsequently to Dur-Šarrukin and finally to Nineveh.

Although in the early second millennium BC the city of Aššur was a significant player on the international scene, as a trading post with widespread interests across the Near East, it was not the capital of a major territorial state. Its citizens operated a long distance commercial enterprise, with branches reaching south to northern Babylonia, eastwards towards the Zagros, and then, most strikingly, northwestwards over the barrier of the Taurus mountains to the network of cities which dominated the Anatolian plateau at this time, primarily Kaneš (Kültepe in Cappadocia), but also others. This extensive commercial network did not survive disruptions in the 17th to 16th centuries BC, and in the 15th century BC Aššur itself was for a while under the hegemony of the recently formed Mittanian kingdom, along with cities like Arrapḫa (modern Kerkuk) and Nuzi across the Tigris to the east.1 In a process for which we have very little direct evidence, Aššur gradually emerged from Mittanian and perhaps also Kassite domination, and asserted itself as a regional power: King Aššur-uballiṭ (1363–1328) famously sought and then claimed recognition from the pharaoh in two of the Amarna letters.2 Assyrian documents from this time remain scarce, and are principally private legal transactions concerned with land acquisition in the vicinity of Aššur, and not until the 13th century BC do we see significant numbers of texts deriving from the practice of government. Assyria in the 13th century was ruled by just three kings, Adad-nirari I, Shalmaneser I and Tukulti-Ninurta I, under whom the territory directly administered from Aššur was greatly expanded.3 Thus it is that not only at the capital of Aššur, but also at a number of towns within the newly established boundaries of the “land of Aššur”, archaeologists have unearthed collections of cuneiform tablets, some small and some very numerous, which were produced by, and so bear witness to, the activities of the Assyrian administration.

The Royal Palace

To appreciate how the scribes, or perhaps we should say the literate administrators,4 of the Assyrian state ran their country, we need to have an idea of the society as a whole and of the fundamental economic conditions under which they operated. The government itself was centred on the royal palace, both as a building and as an institution, and the palace, ēkallu, makes its appearance in the documentation owning, distributing and receiving people and commodities, so it is there that our survey of the land of Aššur will start. The palace was by definition a residence of the king, and at any time in the second millennium, except for a brief episode when Tukulti-Ninurta moved to his new foundation at Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, the king’s primary residence was at the traditional capital, Aššur. It was not always on the same site. Andrae’s team recovered the Middle Assyrian plan of the “Old Palace” constructed above its early second-millennium predecessor, more or less immediately west of the Aššur Temple. This may have been the “palace of Aššur-nadin-aḫḫe”, presumably built by the king of that name who ruled at the beginning of the 14th century. When in 13th- to 12th-century texts we meet the “New Palace” this presumably refers to the large structure erected by Tukulti-Ninurta in the north-west corner of the old city, of which only the platform survived.5 And this may not be all, since one of Tukulti-Ninurta’s palace edicts refers to “palaces in the environs of the Inner City” (ša li[bīt]Libbi-āli).6

The Palace as a Residence

With the construction of new palaces, the older ones may have ceased to function as the king’s primary residence, although they would surely have remained as part of the royal establishment. Despite the absence of any documentation excavated in one of the palaces at Aššur, it seems likely that an extensive royal family would also have been housed in the same building or complex. The first queen herself was referred to as “the woman of the palace” or even just “the palace”,7 while the Court and Harem Edicts (discussed later in this chapter) mention “women of the palace”, who presumably include other “wives of the king” (aššāt šarri)8 and “concubines”.9 In addition we know these ladies were served by slave women (amtu). In the 12th century Archive of Mutta, we meet some of the royal women of differing status and some of the royal children (although in this particular instance perhaps they were not strictly in the king’s harem but that of his regent, Ninurta-tukul-Aššur).

The Court and Harem Edicts confirm the obvious assumption that access to the palace, especially the domestic sector, was tightly controlled. The concept of the “palace precincts” seems to be expressed with the phrase kalzi ēkalli, using a word so far only encountered in this context in both Middle Assyrian and Neo-Assyrian times, but without obvious Akkadian etymology.10 The gatekeepers (etû,utû, Weidner 1954–6, 265) no doubt admitted or excluded visitors, while the official called the rab sikkāti was probably the “key-holder” for doors kept locked,11 but these will normally have been storerooms of one kind or another, as doors through which human traffic regularly passed would not have been sealed with the peg-and-clay sealing system. Fulfilling their duties effectively was evidently important, as the edicts show.

Some of the edicts refer to behaviour while the royal court is on the road: in this situation the palace overseer obviously is not present, and the responsibility for the conduct of the court is in the hands of the “chief usher of the road” (rab zāriqī šaḫūli, Edict No. 20, just quoted). That the court did move around the country is vividly demonstrated by letters found at Durkatlimmu dealing with the arrangements for the arrival of King Tukulti-Ninurta. The party includes six wagons transporting a variety of female members of his household, including the queen, two of her sisters, thirteen other women who are either “our own ladies” (DUMU.MUNUS.MEŠ SIG5ni-a-tu) or Kassite ladies, two flour-processers (alaḫḫinātu) and another woman of obscure function. The king himself and his party, including the Kassite king and his wife, are apparently still en route at Apku.12

The Palace as the Seat of Government

The palace, while serving as a residence, also accommodated a variety of the activities of government. It was the forum for the reception of individuals and delegations from home and abroad, provided storage for valuable items and offered some kind of work or living space for administrative personnel. Unfortunately, despite the recovery of the impressive plan of the “Old Palace”,13 the remains do not betray many clues to the use made of different sectors of the building, in particular, no palace administrative archives have been recovered from there, so this can only be an assumption, although the Archive of Mutta gives a snapshot of some of the visitors received at the site over the course of a year. There is no doubt, though, that institutionally the central state administration was carried out in the name of “the palace”. Thus state-owned commodities which are the subject of transactions are described as šaēkalli, “belonging to the palace”, where in other commercial documents we would read the name of the owner or creditor. The “palace” is therefore an authority, a legal persona or abstract entity, as well as a physical establishment.14 Often this phrase is followed by šaqāt PN, “in the charge (lit. hand) of PN”, which gives us the name of the responsible official, who is thus acting as an employee of the palace. Some such employees have this role explicitly recognised in their titles: “palace scribe”, “palace overseer” (rab ēkalli), “Palace Herald” or “slave of the palace”, and some of them certainly were active on the premises of one or more palaces. Others, like the courtiers (mazzaz pāni), undoubtedly functioned in the palace, but they did not have this role regularly expressed in their titles. Moreover, other officials worked for the palace but not actually inside it: in the cases of the Chief Steward and of Mutta, who undoubtedly both handled palace business, there is reason to think neither of these officials actually operated within the four walls of an official palace, although their archives were found in adjacent areas. It is therefore very difficult to be sure how much of the palace’s business was transacted within the confines of the palace, if defined as a single building complex, and how many of the palace’s staff members or indeed how much of the palace’s property we should expect to find within its four walls.

Although, therefore, we have a number of administrative archives from Aššur at this time, these are in one sense or another “outliers” which illustrate branches of the state’s administration in action, such as the documents from the Chief Steward close to but not architecturally integrated with the palace building. The provenance of a variety of literary and scientific texts in the later debris in the north-eastern part of the city, from the Aššur temple westwards,15 suggests the palace(s) here may have housed a library, but because some of the state’s core administration was housed apart from the palace proper, it is hard to know which other sectors may also have been distributed elsewhere. It is conceivable that the bulk of administrative documentation was written in separate buildings, or, even if it was initially generated by scribes working in a palace, would have been transferred sooner or later to the “Tablet House”.16

Provincial Palaces

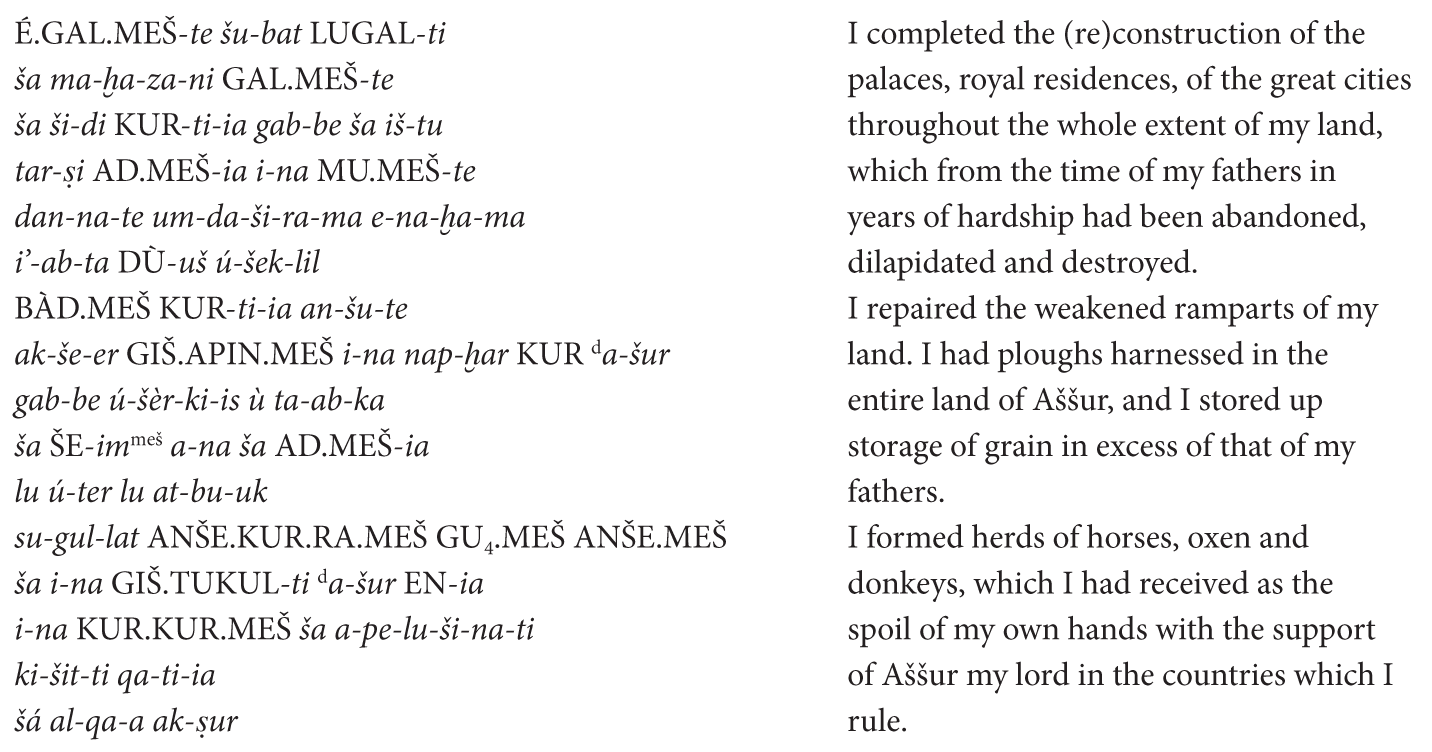

Outside Aššur, the administration of the state was delegated to the governors appointed by the king, and they resided in and carried out their administration from provincial palaces.17 These are sometimes referred to collectively as “palaces across the extent of the land” (šašiddi māti), as illustrated by this account of Tiglath-pileser I’s:18

At Ḫarbu (Tell Chuera), Durkatlimmu (Tell Sheikh Hamad) and Šibaniba (Tell Billa), state ownership of a commodity was consistently expressed by the phrase “of the palace”, and in each case the state archives were found in the palace, high on the principal mound near its steeply sloping edge. This was presumably the governor’s official residence, and we may reasonably assume many of the officials and scribes worked on the premises, if they did not actually sleep and eat there. By contrast, on Ili-pada’s farmstead at Tell Sabi Abyad on the river Baliḫ at the western extremity of the land of Aššur, although there is no doubt that the settlement and its administrators occupied the top of the mound, the establishment is not referred to as “the palace”, maintaining its status as, nominally at least, discrete from the state’s enterprise. This agrees with usage in the first millennium, when “the palace” (ēkallu) referred exclusively to the king’s residences, and not to grand establishments built for highly placed members of the royal family or the government.19

Thus it is that although for some sectors of the state’s administration there is an information vacuum at the centre, this can be filled in part by archives coming from the provinces, especially from Durkatlimmu and Tell Chuera, where most if not all government scribal activity would have been concentrated in a single building serving as the governor’s residence, and would have been responsible for state programmes such as those described by Tiglath-pileser. However, before describing in detail the content of the different archives at Aššur and in the countryside, a brief survey of the land regime and social make-up of Assyria taken from a variety of sources will help to place the state’s activities in context.

People

Since the information we meet in all state archives is either explicitly or implicitly a record of human actions and interactions, every archive contributes to our understanding of the agency of humans in the structure of the state, and an understanding of the role of different members of society is a necessary precondition for understanding the system as a whole.

Personal Identity and Origin

In Middle Assyrian scribal practice individuals’ names are normally introduced by the single vertical wedge (Personenkeil) for male names and the female determinative (MUNUS) for women. Only in filiations immediately after DUMU (“son of”) is the masculine determinative regularly, and after KIŠIB (“seal of”) often, omitted. In private legal or commercial documents, individuals are normally given their father’s, and sometimes also their paternal grandfather’s name.20 It is likely that the inclusion of the father’s name signals “their social status as free-born”,21 and the concept of a free man (a’īlu) is implicit in the Middle Assyrian Laws, where the wording may define the social status of a “woman” (sinniltu) by describing her as “the wife of a (free) man” or “the daughter of a (free) man” (e.g. Tablet A §2). In witness lists at the end of legal documents, witnesses are regularly given their father’s name, and where this is omitted there is probably a reason. Thus in KAJ 51 (Postgate Reference Postgate1988a, No. 16) two of the witnesses have their patronymics as usual, whereas the first witness, Mannu-gir-Aššur, has no patronymic but is given the designation aluzinnu, one of a group of professions associated with cultic performances, sometimes rendered “juggler”. Professions are mentioned only exceptionally in witness lists, and in this case his profession very likely substituted for a patronymic because he did not belong to a normal patriarchal family and thus had no known father (or perhaps even mother).22

In contrast to legal documents, in administrative texts and even in sealed bilateral documents from state archives patronymics are widely omitted.23 Thus in the Babu-aḫa-iddina Archive only in the two land sale documents do we find the names of his father and grandfather given. The omission of patronymics can no doubt be attributed to two factors – the restricted social context in which administrative documentation was produced, which precludes doubts about the identity of the individuals involved, and the greater formality of the legal and commercial transactions which needed to hold their own in the context of public law. Unfortunately, we are not always as familiar as the scribes were with the social contexts, and the lack of filiations in the administrative archives is often frustrating.

Occasionally in both legal and administrative texts a person’s home town or ethnic group will be mentioned rather than the father’s name. Thus in KAJ 101, a sealed and witnessed document, a farmstead is named after Ninuayu, a Burudaean, the ethnic term here substituting for a patronymic.24 In their administrative records the government scribes did not practise any rigid consistency: in MARV 4.1, for instance, a list of “29 captured? workers” (ÉRIN.MEŠ ṣabbutūtu), some are just listed with their names, others are given a profession (“baker”, “gardener”, “goldsmith”, “priest” and an aluzinnu,), and others receive an ethnic tag (kaš-ši-ú, i.e. Babylonian, or šu-ub-ri-ú, i.e. Hurrian); only one of them has a patronymic. Nomads or transhumants were predominantly of Aramaean stock, and are sometimes referred to merely as “a Sutian”, without even their name recorded, but not infrequently the “Sutian” after their names may be further qualified by a more specific tribal affiliation as in “Yurian Sutian” or “Taḫabaean Sutian”.25

Social and Legal Status

One rather special gentilic is “Assyrian” (aššurāyu,aššurāyittu), a term whose occasional usage has proved difficult to interpret. It was thought for a time, on the basis of occurrences in the Middle Assyrian Laws, that it could refer to a social status with diminished legal rights, but this no longer seems likely.26 Instead, it does seem to be used in legal documents to indicate persons with Assyrian ancestry, in contexts where they find themselves under legal or social constraints which are the result of economic distress rather than the consequence of being “Assyrian”. That being Assyrian was a significant and precise condition emerges from other documents, such as a sadly damaged text from the Stewards’ Archive which probably records proceedings presided over by Uṣur-namkur-šarri, who held a range of high government posts under Tukulti-Ninurta I:

Fragmentary though this is, it seems to show clearly that the point at issue was the speaker’s status as “an Assyrian”, a fact which could be established, after which he may have perhaps been repatriated by the good offices of Uṣur-namkur-šarri. Of course “Assyrian” was also used where the person’s precise status was not so central: another Assyrian fugitive (munnabdu) is mentioned in MARV 4.30 rev., fleeing either to or from Karduniaš (Babylonia), and we find Assyrians in a general sense alongside other gentilics such as “Sutians” or “Šubrians”.27 The statement that “I seized the donkey in the hands of an Assyrian” shows that Assyrians must have differed in some recognisable way from others (such as Sutians, perhaps).28 More difficult to interpret is the mention of several chests of tablets in the family archive of Urad-Šerua recording various categories of debts incumbent on Assyrians (e.g. sheep: 1 qu-pu UDU.MEŠ ša UGU áš-šu-ra-ie-e). Given that this family was based at Aššur, one might be tempted to think this meant “inhabitants of the city of Aššur”, but with nothing other than the syllabic rendering of the gentilic /aššurāyu/ (and no preceding logogram for “city”) it is hard to see how this would have been differentiated from the more general ethnic or geographical designation implying “inhabitant of Assyria”. By contrast, KAV 217, recording statements made in a legal context, involves “Aššur-ians” who had taken an oath to the king: there are two mentions of a group, written URU da-šur-a-iu.MEŠ (ll. 10’, 16’), and one of a single “Aššur-ian” (URU da-šur-a-iu l. 13’). The presence of URU here in all three instances suggests that it was not a mere determinative, but stands for āl(u),29 indicating that this specifically means citizens of the city of Aššur and should be distinguished from plain aššurāyu, which would have a wider meaning.30 While being Assyrian was evidently a recognisable and at times important status, it is hard for us to know what range of meanings it might encompass, and we should perhaps resist the temptation to assign it one precise value in all contexts. This is particularly frustrating in the case of the “payments of the Assyrians” listed in the Aššur Temple Offerings Archive, although there too the gentilic /aššurāyu/ is conspicuous for its lack of either KUR or URU preceding.

Debt Slavery

While it is possible that “Assyrian” carried with it the implication of “free-born citizen of Aššur” or “of Assyria”, it is not clear how this would relate to the concept of “(free) man” (a’īlu). However, a’īlu (and probably a’iltu “(free) woman”, although this is not at present attested in Middle Assyrian sources) should be understood to contrast with “slave” (urdu), in its technical sense, and amtu “female slave”. The existence of household slaves is demonstrated by legal sale documents in which ownership of a male or female slave is transferred from seller to purchaser, and by Tablet A of the Middle Assyrian Laws where urdu and amtu are mentioned together and plainly belong together in a legally recognised category distinct from the free man (a’īlu) and his wife and daughter.

Some of these slaves will be normal chattel slaves working in a household and quite possibly born to parents in the same circumstances. However, private legal documents provide clear evidence for the existence of a range of servile conditions which did not amount to full slavery, and were usually related to debt. When taking a loan it was normal for the debt to be secured by a pledge, and this was mostly either land or a person, both referred to in Middle Assyrian as šapartu.31 Failure to repay in accordance with the contract could lead to at least temporary servitude, and there is also the possibility that the debtor would immediately begin a period of service in the creditor’s household in lieu of interest. Two documents referring to release from such circumstances serve to illustrate some of the various situations attested.

This “tablet with the seal of Aššur-reṣuya” must be Ass. 14446ce published as KAJ 167. It is from the same year (and very likely written 3 days earlier although the month name in KAJ 7 is broken), and acknowledges his receipt of the release payment paid by Iluma-iriba for Asuat-Digla, in the form of another woman, either named Šubrittu or simply described as “a Šubrian woman”, which was evidently a precondition of the marriage contract. It gives a few further details which enlarge the picture: Asuat-Digla’s father was called Nirbiya, and she was an Assyrian (aššurāyittu) who had been taken into the household of Aššur-reṣuya under a “keep alive and take” arrangement (balluṭ ūliqi).32

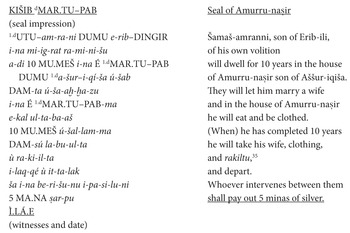

Taken together these two documents attest to the existence of an economically deprived sector of Assyrian society made up of originally free citizens obliged by poverty to tie themselves to richer families. Asuat-Digla was probably placed by her parents in the household of Aššur-reṣuya under an arrangement familiar from other periods of Mesopotamian history and frequent enough to be treated in the Middle Assyrian Laws (Tablet A §39), whereby the receiving family undertook to support (ba/ulluṭu(m) “to keep alive”) a child in return for exercising some rights over it.33 She is here allowed to contract a marriage with a slave in the household of Amurru-naṣir, but although they are not to be his slaves, they will be his “villagers”, and this implies that they will be liable to perform the state service (ilku), presumably attached to the land they will cultivate on behalf of the Amurru-naṣir family.34 That she will be under some legal constraint from Amurru-naṣir follows unequivocally from the fact that it is he who will be retaining in his house the tablet recording her release and it is she who has to roll her seal on KAJ 7 to signify her assent to the contract.

A different type of economic servitude is illustrated by another document from Ass. 14446 in which Amurru-naṣir is involved, published as MARV 1.37. The essence of this text is also worth quoting in full.

As suggested in an earlier edition and discussion of this transaction,36 this seems to be a case where both sides benefit, and Amurru-naṣir’s seal on the tablet means that it will furnish Šamaš-amranni with a guarantee that he will receive his reward after completing the 10 years. There may of course have been a second document sealed by Šamaš-amranni which might be more explicit in specifying what services Amurru-naṣir could claim in return from Šamaš-amranni. Arrangements of this kind are not unique to Assyria: there is a strong resemblance to the story of Jacob and Laban in the Old Testament, and the tidennūtu contracts at Nuzi are concerned with contracts for personal service.37 What this agreement and the situation in KAJ 7 and KAJ 167 have in common is that we see an originally free member of society – Asuat-Digla, or Šamaš-amranni – entering another household in a subservient status, and then in due course being released, either by a release payment or a 10-year limit built into the arrangement. However, in Asuat-Digla’s case, the release is not absolute because she and her children will remain “villagers” (ālāyū) of Amurru-naṣir and his children, and are thereby obliged to perform the ilku duties attached to their status as dependent villagers, to all appearances in perpetuity.

Displaced Persons and Dependent Workers

From Aššur, but also from Tell Chuera and Durkatlimmu, we have a range of lists of family groups of dependent personnel, sometimes characterised as “booty” (šallutu)38 or “deportees” (našḫūtu). The deportation of the population from conquered territories was practised by the Hittite kings. In their royal inscriptions the Middle Assyrian kings mention it only very occasionally: Shalmaneser claims to have blinded and taken captive 14,400 people from Ḫanigalbat after defeating Šattuara, and Tukulti-Ninurta “uprooted” 28,800 “Hittites” from his campaign west of the Euphrates and moved them into “my land”.39 Independent confirmation that such deportations did take place is provided by administrative documents concerned with the maintenance of large numbers of deportees.40 During the reign of Shalmaneser one of the tasks of Melisaḫ and his son Urad-Šerua, as provincial governors, was to organise the distribution of barley rations from the local palaces to deportees on the upper Ḫabur.41 Many deportees were employed in the construction of Tukulti-Ninurta’s new capital, Port Tukulti-Ninurta. Administrative texts recording the issue of grain rations to them (and to other works) were recovered from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, and some of these listing Hurrian families are analysed in detail in Freydank 1980. After Tukulti-Ninurta’s conquest of Babylon, not only the Kassite king and his court, but also numbers of Kassite deportees found their way to Assyria. In a letter in a sealed envelope from the Archive of Ubru addressed to a provincial governor we learn something of the conditions they experienced.42

Although the text does not explicitly refer to these “Kassites” as deportees (našḫūtu), it seems clear that this is what they were. Evidently the state is concerned for their welfare, for whatever motive, and we may compare MARV 1.27 (+MARV 3.54), where a variety of recipients are on the receiving end of an issue of wool totalling 221 talents (about 6,630 kg) issued “on the command of the king as a gift (ki-iri-mu-ut-te)” (l. 35). Most of the wool goes to three groups of deportees – Šubrians, Katmuḫaeans and Nairians – but some goes to individual builders (LÚ.ŠITIM.MEŠ) and architects,44 no doubt all engaged on work at the new capital, Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta.

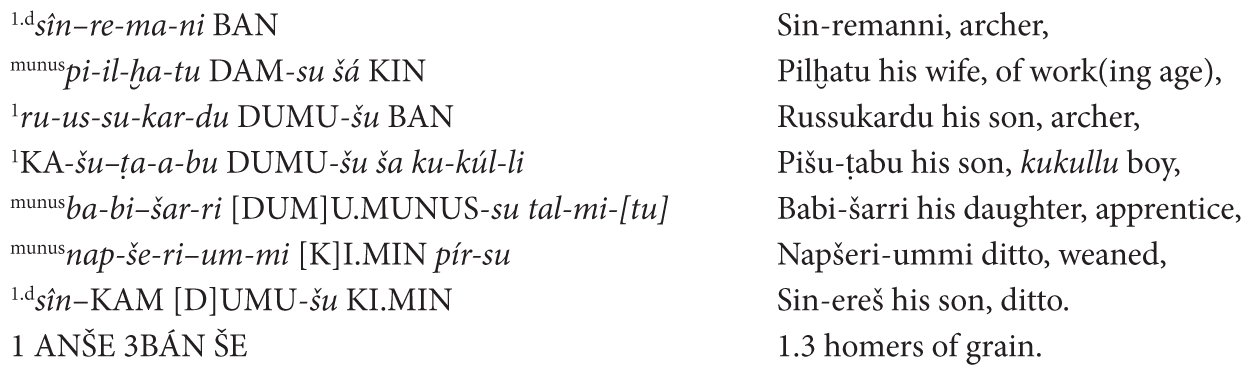

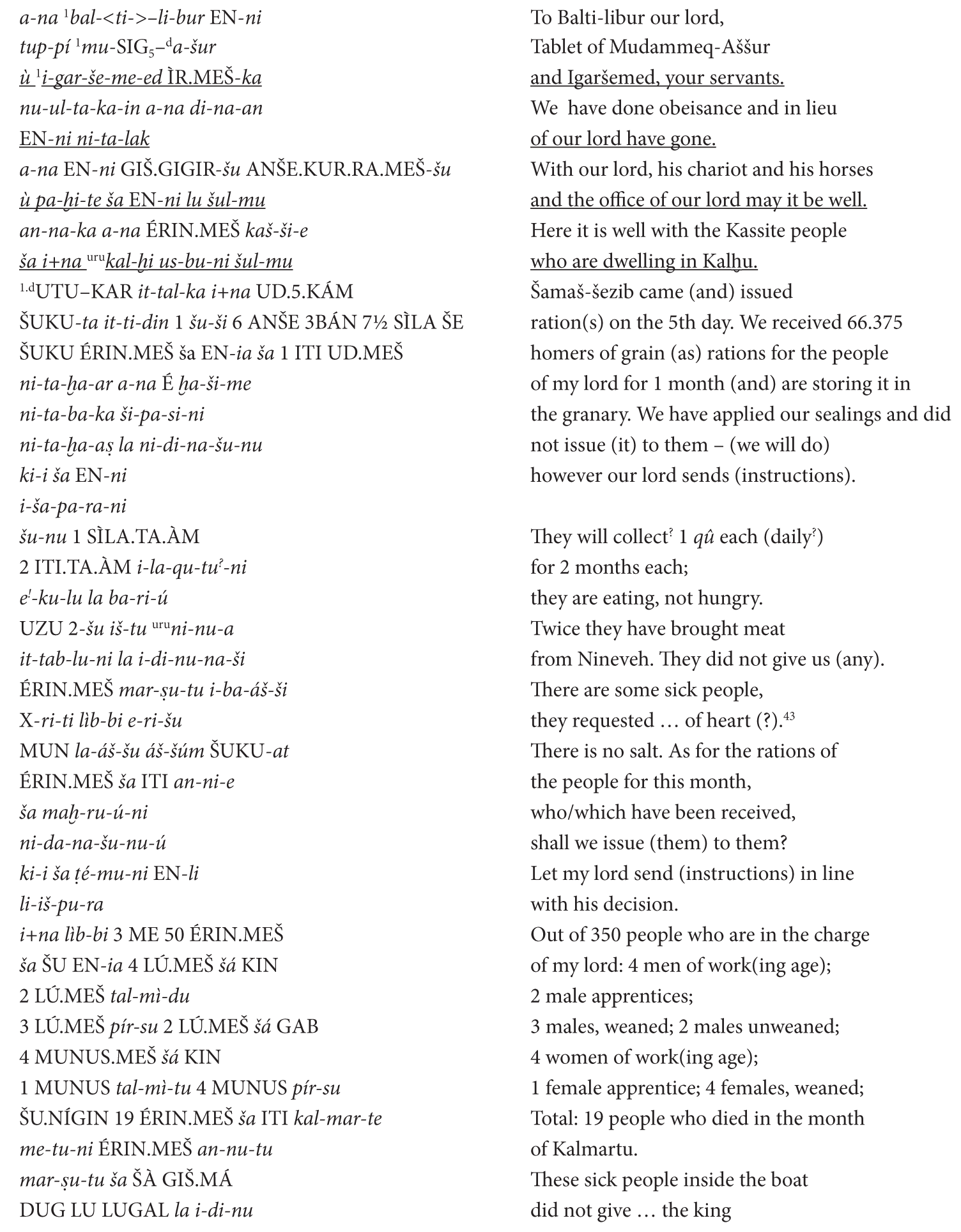

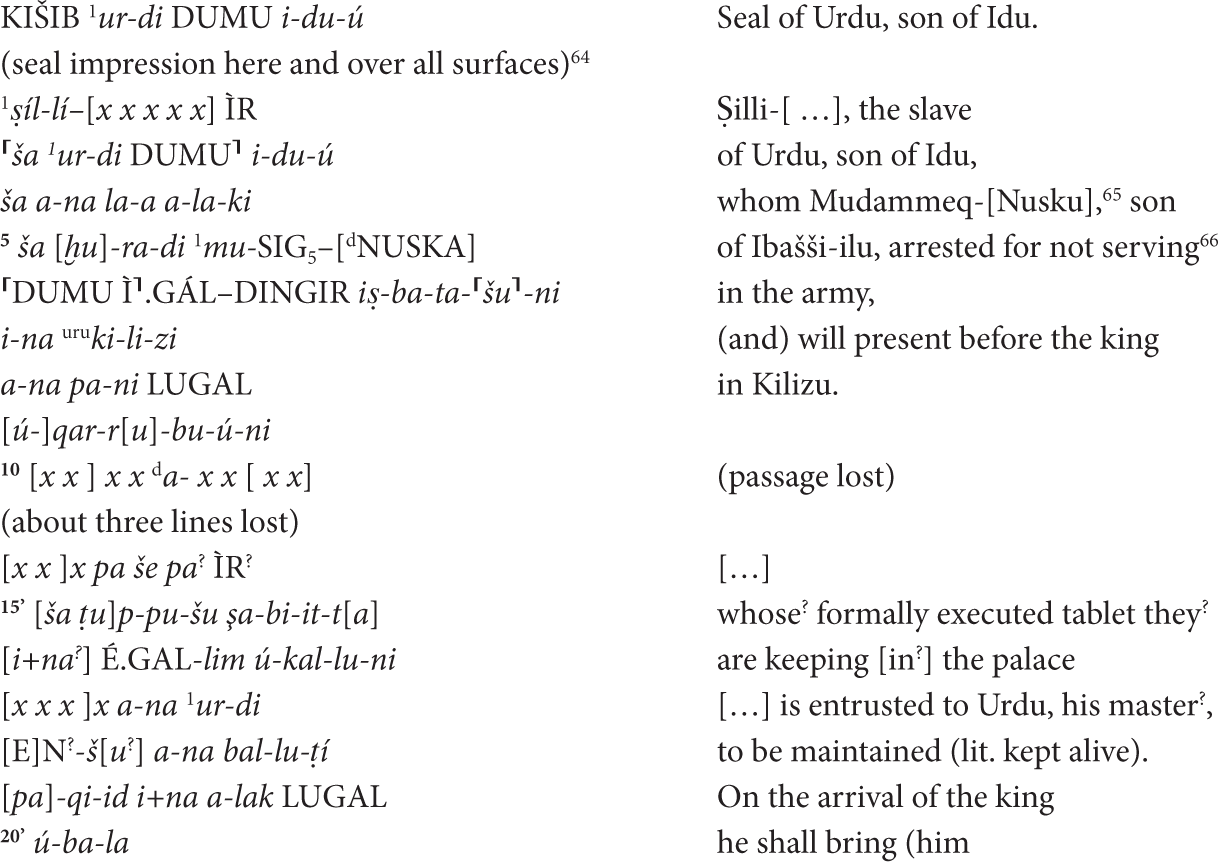

The condition of deportee cannot have been a permanent status, and it seems likely that in most cases such people would have ended up as šiluḫlu, a word of Hurrian origin which refers to a class of dependent labourers, the significance of which has only gradually emerged over the past quarter century as fresh Middle Assyrian texts have been published, in particular those from Tell Sabi Abyad. There, on the extensive estate of Ili-pada in the Baliḫ valley, lists of workers fall into two categories: one is freeborn farmers, where, to quote Wiggermann, the names are practically all “good Assyrian”, and all have their father’s name listed, while the other category is dependent workers designated šiluḫlu, whose names are usually “foreign” and whose patronymic is not given.45 When such groups of non-Assyrians – whether already šiluḫlu or still classed as booty or deportees, or even free families – are under the control (and also the care) of the state administration, the scribes devised a detailed and consistent terminology for describing both the adults and the children. In addition to the regular kinship terms which relate to a nuclear family: wife, widow, mother, mother-in-law, son, daughter, sister, brother, there is a fairly elaborate hierarchy of age groups.

According to this passage, the male head of the family is designated as an archer, with his adult wife classified as šašipri “of work”. In text No. 72 from Tell Chuera, the same family is listed, and there the eldest son, Russukardu, is classified as ušpu “sling(er)”.46 Younger adolescent males are described as šakukulli, a word whose meaning is uncertain but which presumably refers to some weapon or work-tool comparable to the bow.47 Adolescent females are called “apprentice” (and in other texts we have the equivalent term talmīdu for boys of this age). Young children are “weaned” (pirsu for both boys and girls).

This does not exhaust the terminology in use. From two very large tablets from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta listing deported families with their possessions, one short section will illustrate some further terms:

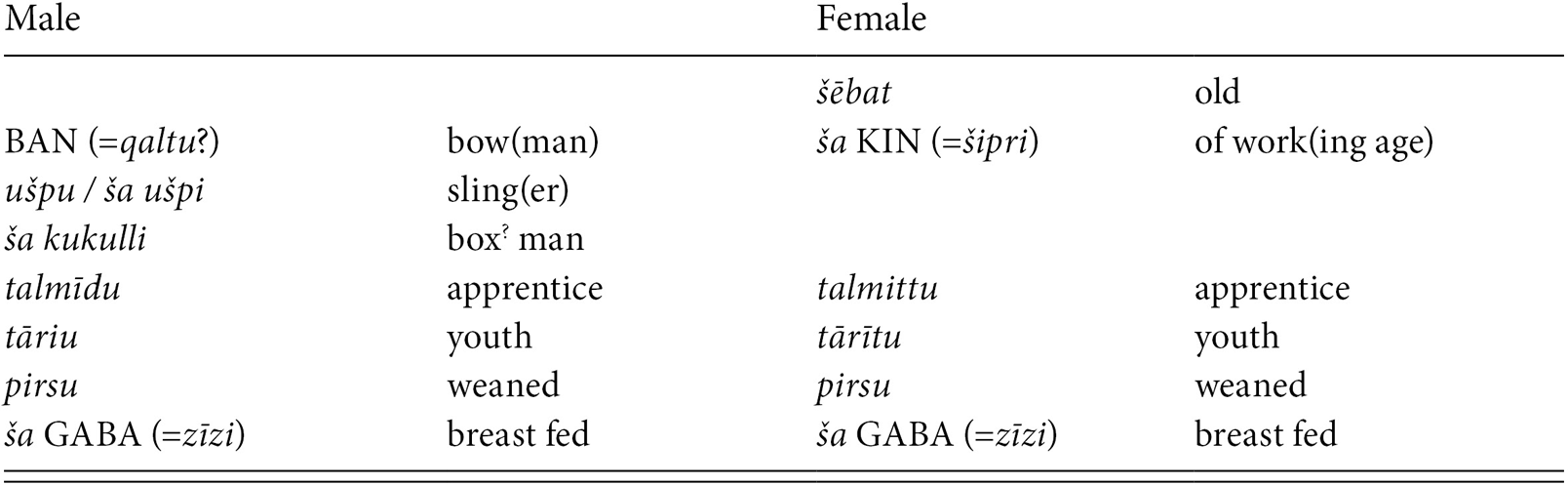

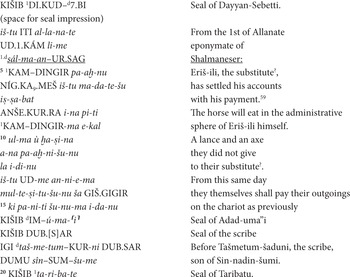

This gives us another age group called tāriu or, for girls, tārītu, of uncertain meaning but slotting between the apprentices and the weaned children, and an unweaned infant classed as ša GABA “of the breast”, which may need to be read šazīzi.48 Taking all together we get the categories in Table 2.1.

Table 2.1. Age designations

This elaborate classification of the workers by age derives from the dual exploitative and pastoral concerns of the administration: on one hand, it was interested in the details of the labour force to establish how many hands it could call on for specific duties, and, on the other hand, it needed to know how many mouths it had to feed, that is the nutritional requirements of the families listed, because the purpose of these lists was to establish the volume of grain required to keep them alive, and/or to supply the officials with the evidence they needed to account for the amounts they disbursed. In some, perhaps all, cases, it may have been a transitional arrangement, before the families, if nominally free, were able to support themselves in due course from the output of their farming or other activities, or if šiluḫlu became dependants of individual Assyrian houses or separate state organisations.

For understanding the social situation of the šiluḫlu, one text in particular is significant, of which the third and final sections are quoted here: 49

This document may well have been drawn up in connection with the division of Šamaš-aḫa-iddina’s estate, as the two opening sections of this text give the numbers of šiluḫlu inherited by the two presumably older brothers, Ištar-ereš (565) and Qibi-Aššur (249). It demonstrates clearly that the rights exercised by the father over about 1,000 dependants were transferred to the next generation of his family. There is no wholly satisfactory English word to convey the meaning of ṣābu (ÉRIN.MEŠ): it is used as a general term for people en masse, male and female, young and old, without implying a precise social class but with the implication that they are under the control of others. Here a comparison with MARV 1.28, which lists some of the people taken into the houses of Ištar-ereš and Qibi-Aššur, reveals that their numbers included two women and a baby,50 so that although one might be inclined to attribute the deaths listed to a military event, this text does not of itself provide evidence that the šiluḫlu might be conscripted into the Assyrian army.

State Labour and Military Service

Given that adult and at least some adolescent male šiluḫlu dependants are classified by their weapons – as archers or slingers – it seems likely that they would have been enrolled to fight on occasion, but our sources do not currently allow us to say if this would have come under the heading of ilku service: if it did, it might have been associated with the ilku obligations of their owners. There is no doubt that free members of society were at times required to fulfil obligations of service for the state, referred to by the word ilku, but the basis for this obligation and how it was administered remain extremely difficult to extrapolate from the textual sources we have at present. Since a survey of the data in 1982, fresh evidence has become available and helps to fill out the picture, without necessitating any significant changes, but some of the underlying issues remain elusive. Succinctly, in the present state of our knowledge it seems true to say that (1) ilku could entail service in the military forces; (2) some (perhaps all) persons carrying out ilku duties did so for restricted time periods; (3) some (perhaps all) ilku obligations were associated with the tenure of land. In other words, we can “rule some things in”, but there are numerous possibilities we cannot rule out.

The first of these three propositions is the easiest to illustrate. Suggestive are the occasions when scribes list arrow(head)s intended for military service (šailki). These are no doubt of copper, and in MARV 5.47 we learn that the steward has taken delivery of “513 arrowheads, 1½ shekels each, for ilku” which three men “and the smiths have brought to the palace for their ilku”.51 From this we cannot tell if the “ilku arrows” were to be used by the persons delivering them, or, perhaps more likely, were a substitute payment from the coppersmiths for their personal service, but it does at least seem clear that some ilku service involved military activity. Comparable to this must be the cases where ilku is mentioned in association with horses, whose role was to draw battle chariots, and with other weapons or supplies appropriate to a military campaign. Three Aššur texts record the receipt of grain as “rations for (the) ilku horses” (ŠUKU-at ANŠE.KUR.RA(.MEŠ) ša il-ki),52 and a similar issue is recorded at Durkatlimmu: “12 homers by the old sūtu, rations for 2 ilku horses, for 4 months – they will eat at 5 qû each”.53 At Tell al-Rimah (Karana or Qatara in the jezirah west of Nineveh), six small documents were found which all involved ilku obligations in different ways.54 Grain as rations for horses is listed in TR 3023 and 2087, and these texts also list straw (IN.NU) and grease (IÀ), both probably intended for the horses, because we know from a Tell Sabi Abyad text that “pig’s fat” could be used as an ointment for horses.55 TR 2087 also lists 53 minas of lead (AN.NA), which later in the text is specified as “[the le]ad, hire of a groom and the ho[rses]”,56 and a sum of 30 or more minas of lead somehow associated with horses is also mentioned in TR 3006, where it has been received by a citizen (with patronymic) referred to as a paḫnu. That this word is likely to be the technical term for a substitute can be deduced from the other definite occurrence, in KAJ 307.57

This agreement, from the eponymate (and so probably the beginning of the reign) of Shalmaneser is evidently between Eriš-ili and other persons including Dayyan-Sebetti, who seals the top of the obverse; although the document is sealed and witnessed, it is relatively informal since patronymics are dispensed with (except for the scribe). Evidently Eriš-ili has been in a contractual relationship with Dayyan-Sebetti and company,60 and both sides are here agreeing to the ongoing terms: there seems to be a single horse, which Eriš-ili will be responsible for feeding, and he is also expected to supply his own weapons, but as before “they” will continue to meet the outgoings on the chariot. Despite the uncertainties (e.g. how will he operate a chariot with a single horse? does he not have his own ilku obligations to fulfil?), it seems clear that Eriš-ili is contracting to serve as a substitute on a recurrent basis. A similar settling of accounts is attested at Rimah by TR 3010 “From the 11th of Ḫibur, eponymate of Adad-bel-gabbe (year 27), Abu-ṭab and Sikku have settled their accounts. Their ilku service is performed ‘in the hand of’ Sikku”.61 That this was a long-term relationship going back two decades is shown by TR 3023, dated to Aššur-nadin-šume (year 7),62 where Sikku receives the horse fodder, straw and grease for Abu-ṭab’s ilku.

The specifically military nature of the ilku service referred to in these texts is indicated not merely by the horses, which imply chariots, but also by the weapons: in KAJ 307 the serving soldier apparently has to supply his own lance (ulmu) and axe (ḫaṣinnu). A lance was borrowed at Rimah by Ṣilli-Marduk in TR 2021+2051 (year 42, reign of Tukulti-Ninurta) and was to be handed back “at the return of” (or “from”) “the army” (ina tuār ḫurādi). This tablet does not mention ilku, but TR 3005 reads: “1.2? homers of grain, 3 qû reedbed-pig’s grease, 3 minas wool, of the army of Niḫriya, who performed ilku-service with his brothers.”63 Although sealed, this is a fairly informal administrative note, since it does not mention any personal names, but for us it is useful in adding wool to the list of items which might accompany someone doing military service, and in confirming that someone returning from the army might have been carrying out his (or someone else’s) ilku service. Soldiers going, or rather not going, to serve in the army are also mentioned in a pair of closely similar Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta documents which make it clear that by the time of Tukulti-Ninurta, if not earlier, arrangements were in place for some citizens to supply men for the army from among their own slaves. This emerges from MARV 4.5, which although damaged can largely be reconstructed with the help of the very similar document MARV 4.6.

Evidently in both these texts Assyrian citizens (Urdu, son of Idu in No. 5, and two sons of Šamaš-mušabši of the city of Ḫiššutu in No. 6) are expected to have sent a slave to the army, but he has for some reason not materialised. He has, however, been arrested by Mudammeq-Nusku, who must be acting on behalf of the military authorities, and the owners are now bound over to keep the slave until he can be brought before the king when he arrives at Kilizu, perhaps on his return from campaign. What fate awaits the slave who has presumably shirked a dangerous expedition, we are not told; but if the owners fail to deliver him, it sounds as though they will have to provide the palace with three other persons, perhaps in perpetuity.

We cannot be certain that the use of the verb alāku “to serve”, for the obligation which the slaves and their owners faced, of itself means that it technically was indeed ilku service, but in this instance it seems likely, especially since in MARV 4.6 the obligation apparently rests on two brothers and is presumably therefore inherited. In other instances it may well be that going to the army is the consequence of other arrangements. A case in point may be MARV 4.119, a tablet relating to serving soldiers and sealed by the provincial governor of the land of Katmuḫu on the northern frontier, in which he is apparently signifying his acceptance of an edict. The text begins:

The point at issue is apparently that soldiers in the provinces named should not make their way into the province of Katmuḫu: “If one single server in the army, from his province or their? village, or while on leave, should enter the land of Katmuḫu, the king has sworn on the life of Aššur his god, they shall leave Ber-išmanni […]”.67

While it seems certain that people who “serve in the army” are incorporated in the military, we cannot be certain that they are necessarily performing ilku service. The phrase could possibly apply to persons serving in another capacity. For instance, if it was normal for an ilku soldier to go on campaign with a lance and an axe, then perhaps the “bow troops who are serving in the army” are in a different category. As we have seen, the adult males among the deported families are described as “bowmen” (BAN), with more junior members classed as “slingers” (šaušpi), and it is obviously possible that they would be incorporated in the army at times, even though they can hardly have themselves incurred ilku obligations through land tenure. This might explain why some persons are expected to supply the administration with large numbers of arrowheads (see earlier section in this chapter on MARV 5.47), perhaps as a substitute payment for serving themselves in person.

This is no more than speculation, and unfortunately the terminology of military ranks and conscription is complex and remains rather opaque.68 We already have persons performing ilku, sometimes involving military service in view of their equipment. We have the word ḫurādu, which certainly refers to military enterprises, sometimes specifying the geographical goal of a campaign, but which can also refer to an individual soldier.69 Further, though, we have a class of persons called ṣāb šarri (ÉRIN.MEŠ LUGAL). They are mentioned as recipients of government-issue military uniforms,70 and in Neo-Assyrian times they appear to be those persons conscripted for ilku who enter the army, as opposed to those assigned to civilian duties. There is a list of 150 “king’s troops” on MARV 2.1, who have linguistically Assyrian names and patronymics, and are sometimes accompanied by sons or brothers, which would all fit well with our understanding of the traditional ilku system. However, in the documentation from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta “king’s troops” are found feeding women (MARV 4.31) or building boats (MARV 4.34) – but this use of military contingents may of course be a consequence of the exceptional circumstances attending the creation of the new capital.

These grain allocation texts from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta offer a wealth of detail which is plainly relevant to the state organisation of military and civilian personnel, but difficult for us to disentangle. Much of the uncertainty revolves round the term pirru, and the cognate adjective perru (or parru?), which at present seem to mean approximately “enrolment procedure” and “enrolled”.

The ÉRIN.MEŠ perrūtu must be personnel enrolled through this procedure, and presumably the “enrolment officers” (EN.MEŠ pirri), of whom there were large numbers (as many as 325 in MARV 2.17:59), were their immediate overseers. What remains obscure at present is whether this whole system of enrolment relates directly to the lists of personnel kept on a number of writing-boards maintained by the central government over a period of some twenty years or longer during the reigns of Shalmaneser and Tukulti-Ninurta. One of these boards (lē’u) was the king’s, and there seem to have been four others each named after an individual: Lullayu, Sin-ašared, Šamaš-aḫa-iddina71 and Adad-šamši. In MARV 1.1 they may have been referred to as “heralds of the boards” (na-gi-ri ša le-a-ni), but this is uncertain for grammatical reasons. In MARV 2.17 we learn that when work was carried out at Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta approximately 1,700 troops listed on Adad-šamši’s board were employed.72 Of these 404 were “army-troops” ÉRIN.MEŠ ḫurādāte), and 560 were “enrolled” (perrūtu), but others come from a range of professions, including 37 exorcists, 17 diviners, 40 scribes of the governor, 22 scribes of the steward, doorkeepers, bird-catchers, transport officials, … 47 deportees, 28 Šelenayans and 8 Šubrian interpreters. It is evident that not all of these can be performing ilku service, and it is hard to suppose that they were all conscripted via an “enrolment” procedure (pirru), though some presumably were. Nor do they seem likely all to be “king’s troops”, and in KAJ 245 the “King’s Board” included women, so we are left at present unsure of the mechanism which recruited this varied body of personnel to state service.73

Crafts and Professions

The Middle Assyrian documents bear witness to a wide range of specialised employments. In many cases, such as industrial or agricultural specialists, merchants or scribes, their activities are evident to us and uncontroversial, but there are also a number of professions which have more to do with social organisation and whose function is less obvious. In most cases, the simple professional designation – “shepherd”, “coppersmith”, “doorkeeper” – is insufficient to tell us how the holder of the title is positioned in the social hierarchy or administrative network, and frustratingly the scribes do not specify people’s professions as often as we would like: in legal documents, the witnesses’ professions are given only exceptionally in addition to their fathers’ names,74 and the internal documents of an administrative organisation frequently dispense with both patronymics and professions because the people involved are well known and need no further identification.

When considering the role of different specialised workers within Assyrian society, one of the most difficult issues to resolve is the relationship between them and their employers. Wherever we see a craft worker – or indeed a merchant (tamkāru) – serving the palace, the question invariably arises whether he (or she) was exclusively employed by the state or could also pursue his (or her) own independent activities, and the same uncertainty applies to large private households.75 It would be otiose to spell out a list of the different crafts and professions, since these have been comprehensively gathered and fully discussed in Jakob (2003). However, for our current purposes two terms merit a brief discussion before engaging with individual archives, as they have a significant role to play in the state organisation. These are the commissioner or representative (qēpu), and the eunuch (šarēšē(n)).76

The qēpu is etymologically a person entrusted with a responsibility, and this effectively meant that he represented the authority who appointed him. In some cases this is the king himself, and we occasionally find men explicitly described as “representatives of the king”, as for instance during a land sale transaction (see §8 of Tablet B of the Laws, and Jakob Reference Jakob2003, 262 for other occasions) although more often they are just given the title qēpu. This is plainly not so much a rank or position, but a formally recognised function. In the case of a provincial administrator at Durkatlimmu it is obviously a long-term appointment,77 but in other cases it is plainly an ad hoc arrangement for a particular occasion.78 Being a qēpu did not exclude having a more specific professional designation. Sometimes qēpūte can refer to a group of miscellaneous officials (cf. p. 8), while in some cases it was probably a person’s specialist skills which made him an appropriate representative. This is visible in the letters of Babu-aḫa-iddina, where we meet groups of his “representatives”: they usually are not given any other title and we remain in the dark as to their special skills, but occasionally someone whose profession we know is mentioned among the “representatives”, and we can see why.79 We several times meet “the representatives for Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta” (e.g. MARV 4.106; MARV 4.18:3; 4.57:21; 9.62:6; 9.36:1), or more specifically “of the granary of Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta” (MARV 4.48:4; 4.60:12). Occasionally a scribe is also designated as a “representative” (MARV 4.31:24; 6.86:17 “of Arbail”; 8.21:14), and more than once a son of the king is named as a qēpu (MARV 4.34:23; at Durkatlimmu, see Jakob Reference Jakob2003, 26956), as are certain well-known, high-ranking officials from Tukulti-Ninurta’s court, several of whom may at the same time be defined as a “eunuch of the king” (ša SAG LUGAL qe-pu).80

The Akkadian reading of LÚ.SAG in Neo-Assyrian texts is unquestionably šarēši (as demonstrated by its appearance as a loanword in Aramaic and other languages). Middle Assyrian normally writes ša/šá SAG, and its formal equivalent must use the dual form, which is written syllabically ša re-še-en in the Laws. In both Middle and Neo-Assyrian times, the meaning eunuch is beyond doubt in some contexts, and I have seen no convincing argument not to extend this meaning to all Assyrian texts, whatever the situation in Babylonia.81 As in Neo-Assyrian times, it is noticeable that certain Middle Assyrian persons bearing this title use seals which show a beardless adult male (for Uṣur-namkur-šarri see Fischer Reference Fischer1999, 122).82 In Middle Assyrian texts šarēši (or šarēšēn) are almost always “of the king”,83 and as just mentioned, under Tukulti-Ninurta some of the king’s eunuchs were on occasion appointed as his representatives (qēpu). Uṣur-namkur-šarri also held a variety of high offices under Tukulti-Ninurta, and his contemporaries Libur-zanin-Aššur, who dedicated an agate “eye stone” inscribed with his name84; Dayyan-bel-ekur and Dayyan-Aššur85 were other eunuchs holding high office. Eunuchs are mentioned in the context of palace decrees, where they have dealings with some of the palace women, but guarding the harem was certainly not their only function; Jakob is able to delineate a range of managerial activities undertaken by individuals known to be eunuchs (2003, 66–92).

Land

The most fundamental structure of the Assyrian state consists of the relationship between people and land. The state’s essence is to be “the land of Aššur”, and the Assyrian coronation ritual charges the monarch with a duty to “extend your land” (rappiš mātka). Part of the same ritual involves the (re)installation of high officials, including “any office holder” (attamānu bēl pāḫiti), with the king telling them to resume their office.86 The title bēl pāḫiti (the Assyrian dialect equivalent of the Babylonian bēl pīḫati) literally means no more than someone with a responsibility, but in Assyria during the 13th century it comes to refer specifically to the governor of a territorial province.87 In this context it partly or entirely replaces the earlier title ḫassiḫlu, best attested in the texts from Šibaniba (Tell Billa).88 This has a hybrid origin, with the Hurrian professional ending -(u)ḫlu attached to the Akkadian word ḫalzu, which is attested in the early second millennium in northern Mesopotamia and Mari as meaning a province and still holds that meaning in Middle Assyrian texts.89 The term bēl pāḫiti becomes so closely identified with the provincial governor that very soon (at latest by the reign of Shalmaneser) pāḫutu on its own came to mean “province” as is evidenced by the two provinces established on the lower Ḫabur, “Upper Province” and “Lower Province”.90 As we shall see, the regime of contributions to the Aššur Temple was organised province by province, and they may be summed up as “offerings received of the provinces” (gi-na-ú maḫ-ru ša pa-ḫa-a-te.MEŠ MARV 7.22). From correspondence and administrative documents in various archives it is clear that the provincial governor, based at a provincial capital which usually gave its name to the territory he controlled, was the agent through which the central government administered its territory.

In this role the governor represented the king and administered the rights of the monarch over the land within his province. What precisely those rights were, is a much more complex question. In the writer’s view, the crown notionally exercised a sovereign right over all land within the boundaries of the “land of Aššur”, and this was the premise on which the ilku, or state service, system was organised. In practice, though, the state, and its legal system headed by the monarch, would have recognised traditional rights to ownership of land, both in the Assyrian heartland round Aššur and in more remote and recently annexed provinces, even if in particular circumstances it also implemented annexations or confiscations of land into the state’s possession. The theoretical issues behind the land-owning situation are too complex and keenly disputed to address here, and therefore we move on to consider the evidence for various classes of land regime under the Middle Assyrian kings.

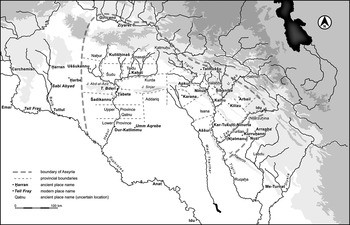

Figure 2.1. Assyria in the 12th century BC showing hypothetical provincial boundaries.

Private Land Tenure

While the archives with which we are principally concerned understandably tell us more about state-administered land, this should not blind us to the probability that most agriculture was undertaken by the private sector. At present, the only substantial evidence for private land tenure comes from Aššur. Agricultural conditions around the capital must have differed significantly from the upper Ḫabur and other northern provinces of Assyria. In the first place, Aššur itself is far enough south for rainfall agriculture to be a precarious subsistence strategy.91 Economically, as the city itself grew it may have outstripped the carrying capacity of the fields in its traditional hinterland: this must have consisted of narrow strips of fertile alluvium along the valley bed of the Tigris, which could be irrigated by simple gravity flow, supplemented by whatever crops could be won in good years from dry-farming enterprises or hand-watered plots in the surrounding countryside.92 Undoubtedly in the traditional Assyrian heartland, but also perhaps in more recently annexed territories, there was a long-standing regime of private landownership which we would not expect to generate documentation preserved in the archives of the state administration. There is little documentary evidence for state involvement in agriculture around Aššur (though as we shall see there are important texts from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta across the river), but the Ass. 14446 archive (Pedersén’s M9), dating mainly from the 14th century, before the state’s annexation of the Ḫabur triangle, gives us a glimpse of the exploitation of rural settlements west of Aššur by the urban elite, shedding light on local land tenure and its role in the economy. Many of these tablets are loans of lead from members of urban families to villagers, backed up by pledges of land.93 They do not follow a rigid formula, but KAJ 14 is typical in several respects.

Land pledge texts like this one show plots of agricultural land in villages, in danger of passing from their previous owners into the hands of certain Aššur-based families. The villages are described as “across the Šiššar”, a water course plausibly identified with the modern Wadi Tharthar, some 30 to 40 kilometres west of the Tigris.96 One is named after an individual, Ili-itt(i)-ilu; the others are “Cistern of the Palace” (Gubbi-ekalli) and “Well of the water channels” (Bur-raṭati) – all hinting at relatively recent exploitation requiring some form of irrigation, supported by two of the documents relating to Bur-raṭati which mention shadufs.97 Nissen compared the style of the seals used by different groups on these tablets. Since they were the purchasers, we would not expect the members of urban families to have sealed the tablets, and Nissen demonstrated that the occasional more sophisticated and recognisably Assyrian seals would have belonged to the scribes, who must also have been based at Aššur, whereas the much more frequent and simpler Mittanian-style seals were used by the villagers whose lands were used as security or who acted as witnesses.98 As the closing lines of KAJ 14 illustrate, the documents we have are not definitive title deeds (called in Middle Assyrian tuppu dannutu), but provisional documents authorising the intending purchaser to possess and exploit his land.

Thus an area of 20 iku (~7.2 ha) is to be selected (by the current owner) in KAJ 14, and placed at the disposal of the creditor for the 6-month duration of the loan, but thereafter if repayment is not made the land will be sold. This would involve further legal proceedings to free the land of other claims, and must reflect the fact that in the traditional rural community plots of land were administered in such a way that a family did not have an absolute entitlement to specific pieces of ground, but was assigned the right to cultivate a given area within a larger unit, the precise piece of land being determined by the drawing of lots (pūru). Evidence for this practice, which was partly in place to organise and standardise the alternate year fallow regime, is found in occasional Middle Assyrian (and indeed Neo-Assyrian) texts, and is also detectable in the badly damaged Tablet B of the Middle Assyrian law codes.99 This shows that land could be delimited by a “great boundary of partners” (taḫūmu rabi’u šatappā’ī), within which lay “lots” (pūru) divided by “small boundaries”.100

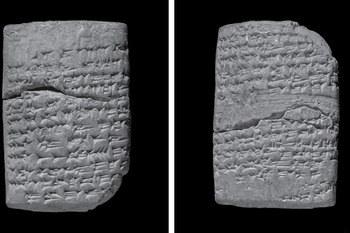

Figure 2.2a. Fourteenth-century century land sale document from Aššur (BM 108924).

Figure 2.2b. BM 108924, to show positioning of seller’s and witnesses’ seals and captions (after Postgate & Collon 1999–2001, pp. 12–13).

The major boundaries were important, as indicated by the penalty for removing one. In the following section (§9) lesser penalties are exacted for removal of “the small boundary between lots” (taḫūmu ṣaḫru šapu-ra-a-ni), a phrase showing that the small boundaries delimited plots allocated by the drawing of lots. This procedure is attested in Middle Assyrian texts by KAJ 139, which refers to second, third and fourth lots, and by KAV 125–9 mentioning fourth, fifth, seventh and ninth lots. KAJ 139 is from the Ass. 14446 archive, and must belong in the context of a land purchase where a number of existing landowners own lots in two different fields. Two of the owners are “clear” (za-ku-ú); a third, Abu-ṭab, plainly is not as the fourth, Ibašši-ilu, “takes recurrent responsibility for clearing” him (pa-ḫa-at1a-bu–DÙG.GA za-ak-ku-e [1Ì.G]ÁL–DINGIR-ma it-ta-na-aš-ši). This illustrates vividly one of the preliminaries to a land purchase in traditional agricultural areas, that is the process of “clearing the field of claims” as required by KAJ 14, and we see that it involved the cooperation of various members of the village community. Putting the 20 iku at the disposal of his creditor – who was not a member of the existing village community – obliged the debtor to “select and take” a specific area of land, separating it off from the communally administered plots, and this was of course the first step towards the community’s final loss of control over its traditional lands. The requirement to measure the field and prepare a “valid tablet”, reflecting state control of the land regime, is regularly encountered in the land sale documents of the Ass. 14446 archive and is illustrated by another section of the laws.

There are numerous points of interest in this law. One is the expectation that the real estate being acquired will be in a village away from Aššur itself, which entails the involvement of both officials in the capital and local authorities. There is little evidence from outside Aššur illustrating the land tenure conditions in the provinces, but the Urad-Šerua family’s land holdings in Šarika, along with other documents from their archive (Chapter 4.5), provide evidence from the 13th century for the urban elite’s interest in rural property, and there is evidence from Tell al-Rimah in the jezirah to the west supporting the picture of a countryside linked in various ways to the city. Also from Tell al-Rimah comes a rare land sale document from outside Aššur, which prescribes that the purchaser “shall encircle the field (to measure it), and according to the edict of the king he shall have the herald make an announcement”.102 The verb ušalba “encircle” here replaces “measuring with the royal rope” and is a usage otherwise known to us from Nuzi rather than Aššur (CAD L 76), suggesting traditions which may have persisted from Mittanian times, but the rest of the phrase requires adherence to the procedures decreed by the king.

Another point of interest in Tablet B §6 is the whole process of “clearing” the property of other claims and the importance attached both to the presentation of written evidence for any claims and to the completion of further documentation to finalise the transfer of ownership.103 A chest full of “tablets of the herald’s proclamations” for houses in the city of Aššur is listed in the inventory of Urad-Šerua’s storeroom (see p. 242), and immediately after that a chest of “clearance(s) of people and fields of the town of Šarika (tazkīte ša ÉRIN.MEŠ u A.ŠÀ.MEŠ šauruŠarika)”, which again underlines the role of formal legal documents in the procedures required for the purchase of property whether at Aššur or in the countryside. As at Tell al-Rimah, the requirement in KAJ 14 and similar documents to measure the land “with the king’s rope” and to write the final property deed “before the king” emphasises the state’s direct concern to control the regime of landownership across its territory. This may in part reflect the king’s role as the principal judicial authority (in which role he retained the title uklu “overseer” specifically in relation to land entitlement until the end of the Assyrian Empire in the 7th century), but it must also link to the system of state service (ilku), which was probably formally attached to any private landholding in the land of Aššur, and is occasionally mentioned in the context of land tenure.104

State Farms

Even if private landownership (albeit conditional on ilku obligations) may have been the norm, the state did manage its own estates, as the texts from Durkatlimmu demonstrate. They clearly show that a provincial government could administer a number of farms for which the chief farmers were allocated fields amounting to multiples of 100 iku (ca. 36 hectares) primarily for barley cultivation, although they were also expected to produce sesame and wheat, and at Durkatlimmu at least there were separate, smaller plots established on irrigated land.105 Looking at the evidence for the yields recovered, compared with the different demands on the provincial administration’s stocks of grain, the scale of the operation at Durkatlimmu may seem surprisingly small, but texts from Aššur using an extremely similar formulation suggest that this may not have been exceptional. The areas and yields recorded for Nemad-Ištar, in the jezirah between Nineveh and the Ḫabur, with a total of state-cultivated land of 600 iku (~216 ha.) were in the same order of magnitude, as were the comparable texts dealing with Turšan and Ḫiššutu.106 It is clear that from at least the reign of Shalmaneser the central government installed an agricultural regime administered by the provincial authorities in different regions of the state for the production of grain and other crops. Much of the harvest each year went back into seed corn and rations for the plough oxen and farm labourers, but in good years there was a surplus to fill the provincial palace’s granaries. Nevertheless the amounts involved are by no means huge, and it is plain that this was not in any way a complete state takeover of the local economy.

Prebendary Allocations of Land

This is not the whole picture. From Tell Chuera there is clear evidence for two other ways the state promoted agriculture. On one hand there are small (2–3 iku ~0.72–1.08 ha.) plots of land assigned to individual members of the local governing cadre of Assyrian officials, numbering about 30 in all. Plots this size, as pointed out by Jakob, cannot have been sufficient to sustain an official and his family throughout the year, so this was presumably only one part of a package of remuneration. The situation must partly have depended on whether the majority of the governing cadre consisted of local residents, with a pre-existing subsistence base they could fall back on, or were rather state employees posted to a remote part of the kingdom, who would have needed more substantial state support. At Chuera they are referred to as “Assyrians”, presumably to distinguish them from the locals, and this suggests that we should see them as more of a colonial garrison, planted on a partially deserted landscape to act as a secure staging point on the route to the west, rather than a surviving pre-Assyrian population which maintained its presence.

In either case, there must have been cultivable land available to the state authorities which could be allocated to its dependants, and the Chuera archive also includes a number of texts demonstrating the establishment of farms staffed by “Elamites” with their entire families. We know of no obvious occasion on which the 13th-century Assyrian kings might have captured large numbers of ethnic Elamites. As noted by Jakob, while many of the people in these lists do have distinctly non-Assyrian and in some cases clearly Elamite names, others have good Assyrian names, and this suggests that the population in question had already spent some time within the cultural ambit of the Assyrian state. The term našḫūtu “deportees” is not applied to them in the texts we have, so they should not be viewed as recent deportees, but perhaps as willing “agricultural colonists” taking part in a state programme of rural expansion. The texts we have are concerned with rations issued to them, so that they are economically dependent on the state, but included with the rations is an allocation for seed corn, at a level suggesting that each family may have been allocated a plot of 2 iku (~0.72 ha.) to cultivate (Jakob Reference Jakob and Janisch-Jakob2009, 98). Particularly tantalising is text No. 73 from Chuera, which does, as Jakob proposes, strongly suggest that similar arrangements may have been made for incoming “Assyrian” families (since children are mentioned), and that we may be right to see this as a deliberate state policy of encouraging agricultural colonisation within the private sector.

What is very evident is that the administration of land at Chuera was strongly determined both by the local environment and by the transient political circumstances, and should not be viewed as some kind of generalised organic process. Politically, the site of Tell Chuera may not have been a significant settlement under the Mittanian regime, but it certainly fell within Mittanian territory and the Assyrians must have represented a foreign power when they first took over the district. Environmentally, the prospects of a sequence of adequate annual rain-fed harvests must have been better than at Durkatlimmu, more than 100 kilometres further to the south and so receiving less annual rainfall, but there was probably less opportunity to cultivate a large area of irrigated land since Chuera is a long way from a major watercourse.

At Aššur the Urad-Šerua Archive contains a few texts which look as though they list plots of state land allocated to state employees (pp. 255–6).107 While it is not clear how these tablets relate to the family’s private archive, the mention of Urad-Šerua himself in No. 74 does suggest that they are not completely out of context. Each is different: No. 71 has difficulties of interpretation, but lists plots, ranging from 10 down to 2 iku, each associated with an individual; filiations are unfortunately not given, but some of these are names borne by highly placed members of the administration, and all bear good Assyrian names, which is compatible with their being members of the urban elite from Aššur. The plots are in a town or village whose name is damaged, but the following line appears to mention Nineveh. There is then the name of Aššur-naṣir, mayor (ḫaziānu), and a line which seems most likely to read “of the writing-board of (ša le-[‘i])” Mudammeq-Marduk. The tablet is impressed with a seal bearing Mudammeq-Marduk’s name and giving his title as “Governor of the Land”; he and Aššur-naṣir the mayor again are similarly mentioned at the end of text No. 72, which lists houses assigned to some of the same individuals (and coincidentally is dated to his own eponymate).

The plot sizes in No. 71 are on average larger than those issued to the cadre of Assyrian staff at Tell Chuera (see p. 38),108 and it seems that some of the recipients also received a house. If it is correct that they are some or all members of the Aššur establishment, it is unlikely that they would propose to reside permanently in this new house in a rural settlement, and we should probably regard these allocations as a form of prebendary remuneration which enabled them to maintain an economically dependent, if not socially inferior, family there and so to benefit as landlords from their cultivation of the agricultural plot.109

Figure 2.3. Aerial view of Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, 1973.

Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta

Text No. 74 of the Urad-Šerua Archive is rather different; its obverse seems to mention issues of palace seed grain for the cultivation of areas of land, and on the reverse are listed a number of very highly placed individuals, including Libur-zanin-Aššur, royal eunuch, Aššur-bel-ilani, a royal representative (qēpu), and Urad-Šerua himself. It is unfortunate that so much of this tablet is lost that we cannot confidently reconstruct its content, but recently published texts from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta provide a dossier of evidence for the allocation of prebendary plots to state officials, including Libur-zanin-Aššur and others high in Tukulti-Ninurta’s hierarchy (Freydank Reference Freydank2009a). One of the principal events of his reign was the creation of a new capital city, named after himself, on the left bank of the Tigris not far upstream from Aššur. This was called Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta (The Port of Tukulti-Ninurta), and the site (Tulul el-Aqr) was excavated by the Aššur expedition in 1913.110 One of his inscriptions, on a stone slab from the vicinity of the new ziqqurrat, describes the initiative as follows:

Here then the state was taking control of an area of previously uncultivated land, presumably on the terraces above the alluvial river flats, where an irrigation project from the Tigris or Lower Zab some distance upstream was needed. Tablets from the excavations allow us to glimpse the process of allocating the land in action. Some of it was designated the property of the palace and entrusted by the royal representatives (qēpūte) to officials for cultivation: an example of this is MARV 4.106, where the responsible person, Innamer, is simply called “the supervisor of the fields” (ša UGU A.ŠÀ). The tablet is sealed by Innamer, and is effectively a work and delivery contract, supplying him with seed corn and fodder for the plough oxen (but no rations for workers, unlike the Durkatlimmu texts), and requiring him to deliver the harvest.

The eponym Abattu (presumably the first of that name) belongs at least 10 years into Tukulti-Ninurta’s reign (Röllig no. 33113). MARV 9.62 (Freydank Reference Freydank2009a, 24) is a very similar bilateral contract drawn up on the same day between the Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta representatives and Marṣanu, who is only identified by his father’s name.

Here then we see the state retaining possession of the newly created fields and their produce, directly controlling the agricultural activity and employing its own officials in a contractual mode. A different mode is reflected in MARV 9.18. The lines summing up the content of this tablet run as follows:

PAB-ma 1010 IKU me-ru-šu šaurukar–1GIŠ.KU-ti–MAŠ

i-na lìb-be 110 ANŠE EN.MEŠ ŠUKU.MEŠ

44 ANŠE a-nagi-na-e 1 ANŠE 6BÁN ša x[ ]x-ši-i

10 ANŠE 1me-li-ḫu-um-ba 4? ANŠE 4BÁN 6 SÌLA NINDA?.MEŠ

7 ANŠE 8BÁN ŠUKU ANŠE.KUR.RA.MEŠ

1 ANŠE 4BÁN 6 SÌLA MUNU5?.MEŠ-te

te-li-it BURU14ša li-me1SU–dAMAR.UTU

“Total: 1,010 iku cultivated land of Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta. Therefrom:

110 homers – prebend-holders

44 homers for the fixed offerings

1.6 homers .……

10 homers – Meliḫumba

4.46 homers bread?

7.8 homers – rations for the horses

1.46 homers – malt?

Harvest yield of the eponymate of Erib-Marduk.”

The first line of the tablet gave the column headings for three sets of figures: “Fields of dike? and farmstead?” (A.ŠÀ ša E ù du-ni), “Their grain yield” (ŠE-umte-li-su-nu) and “Fields they are not [cultivating]” (A.ŠÀ la i-r[u-šu]). While these categories are not entirely clear, the text does explicitly identify some of the produce as going to the fixed offerings, as Tukulti-Ninurta’s inscription would lead us to expect, but also uses the term prebend-holders (EN.MEŠ ŠUKU.MEŠ), which provides confirmation that the practice of assigning plots of land to state officials, deduced from the texts from Aššur and elsewhere, can accurately be described in this way. The total of 110 homers assigned to prebend-holders is more than half the total yield. If each of them managed their own plots, it is unclear why the state should list their individual amounts, so possibly the entire area of 1,010 iku was farmed as a single operation and shares of the harvest were allocated to the prebend-holders and other recipients in proportion to their nominal landholdings.

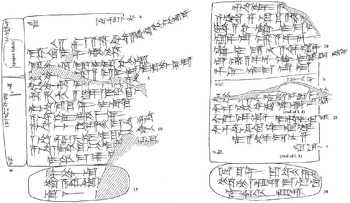

This tablet, dated to Eriba-Marduk, comes from near the end of Tukulti-Ninurta’s reign, but allocations of prebend land were certainly made earlier in the reign.114 The most detailed evidence for this is provided by the remarkable tablet VAT 21325 (MARV 4.173), dated some years earlier (Salmanu-šumu-uṣur, Röllig 42, not before Tukulti-Ninurta’s 18th year). It is, unusually, wider than it is high, and ruled into 16 columns which continue round the right-hand edge of the tablet and onto the reverse, contrary to the usual disposition of text on a cuneiform tablet.115 The reason for this unusual format is that the scribe needed to record the landholdings, arranged horizontally in Cols. i–xiv according to their location, assigned to some 15 individuals or groups, listed vertically in Col. xvi.3–18. The landholders include a number of high officials known from other texts, including Uṣur-namkur-šarri, perhaps at this date the governor of Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, and Aššur-tapputi. They are listed as individuals, but five of the entries are for the “decury” (10-tu = ešartu) of an individual, again including Uṣur-namkur-šarri, but also the other well-attested eunuch of Tukulti-Ninurta’s reign, Libur-zanin-Aššur, and Mušabši-Aššur, known as a son of the king and a qēpu.116 The landholding in xvi.17 is attributed to “the king”, and that in xvi.18 once again to Uṣur-namkur-šarri. The headings for Col. i–xiv specify the location of the fields: these include at least four villages (ii, vii–ix),117 the “commonland” (A.GÀR) of Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta (xi) and of “the village of Ili-ayabaš” (i), a marsh area (appāru; ii) and a lake (“small sea”, vi). Col. xii mentions an orchard, and in Col. x probably “the cultivated area of Uṣur-namkur-šarri”.

Figure 2.4. Land register from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta (Freydank, MARV 4.173).

The documentation from Kar-Tukulti-Ninurta, which includes further texts attesting to the prebend regime, discussed at length in Freydank (2009a), reflects a similar situation to Tell Chuera, in the sense that we are looking at land brought into cultivation by the state’s initiative, partly managed directly as a state enterprise and partly assigned to servants of the state in remuneration for their service. The Assyrian occupation, one may almost say colonisation, of the western territories referred to as Hanigalbat goes well back into the reign of Shalmaneser, and by the time Tukulti-Ninurta came to the throne there were decades of experience of establishing and administering state-controlled cereal production and allocating plots of land to provide for the subsistence of employees of the state (cf. Freydank Reference Freydank2009a, 58). It may have been exceptional, in that land so close to the capital would surely have been exploited earlier if it had not required irrigation, and was therefore dependent on the royal project to secure the labour for constructing an entirely new canal. The fragmentary evidence discussed earlier from the Urad-Šerua Archive for prebend land assigned to high state officials in the Nineveh region seems to show that the state disposed of land in the provinces for this purpose, but it is hard to be sure whether this was because it had no suitable land nearer to the capital, or because the higher rainfall on land further north made it preferable.

Tell Sabi Abyad

The most detailed picture of an Assyrian agricultural enterprise will surely come from the much larger archive from Tell Sabi Abyad. While the majority of the texts from here are still to be published, very significant work has already been done by Wiggermann in reconstructing the conditions revealed by the archive.118 Today the mound of Sabi Abyad sits in the valley of the Baliḫ river, east of the main stream, some 45 kilometres south of Ḫarran and west of Tell Chuera. A Neolithic settlement had left a tell on which a small fortified farmstead was erected in the Mittanian period. With the arrival of Assyrian rule, probably under Shalmaneser I, a new fortified building occupying 60 by 60 metres (perhaps not coincidentally one iku) was constructed on the site of the Mittanian fort, and from within the walls of this enclosure the Dutch expedition recovered an archive of about 315 tablets (Wiggermann Reference Wiggermann and Jas2000, 1756). The settlement was a dunnu “fortified farmstead”, and for much of its existence it was the property of the Chief Chancellor (sukkallu rabiu), Ili-pada, who was a member of the parallel royal dynasty sometimes given the title “King of Ḫanigalbat”, and contemporary with the later years of Tukulti-Ninurta I.119 The majority of the tablets derive from the archives of the stewards (AGRIG) who controlled the activities of the dunnu: for most of the period covered this was Tammitte, but before him Mannu-ki-Adad also served his time as the steward.120 The final publication of the complete archive will doubtless shed much light on the role of the stewards in the dunnu. It appears to have been organised very much along the same lines as state establishments in the provinces such as Ḫarbu and Durkatlimmu. Tammitte managed as many as ten flock-masters (nāqidu), and was authorised to exact a penalty of 100 strokes on them if they missed the annual count,121 while his predecessor Mannu-ki-Adad’s duties included issuing sickles to the workforce: