There appeared a great sign; a snake, his back blood-mottled, a thing of horror, cast into the light by the very Olympian, wound its way from under the altar and made toward the plane tree. Thereupon were innocent children, the young of the sparrow, cowering underneath the leaves at the uttermost branch tip, eight of them, and the mother was the ninth, who bore these children. The snake ate them all after their pitiful screaming, and the mother, crying aloud for her young ones, fluttered about him, and as she shrilled he caught her by the wing and coiled around her. After he had eaten the sparrow herself with her children the God who had shown the snake forth made him a monument, striking him stone, the son of devious-devising Kronos, and we standing about marvelled at the thing that had been done.Footnote 1

The Earliest Sources

The practice of taking directions, counsels, omens, and divinations from birds, known as ornithomanteia, has been described as one of the oldest scientific practices in the world.Footnote 2 As was hinted in the previous chapter, this circumstance springs from the silent fact that many bird species and humans coevolved and share a long and interwoven cultural history. Another reason for this rests with the independent agency of avian creatures. Bird intra-acts.

The oldest textual sources of the perplexing practice of bird divination originate from Mesopotamia, from where the knowledge was passed on to the Hurrians.Footnote 3 The texts describe how the flight of birds, their behavior, and intra-actions with each other, as well as with other animals and humans, were taken as signs from the gods. Reliable seers were sought after. In the Amarna correspondence from the fourteenth century BCE, for instance, we can read how the king of Alasia on Cyprus was in desperate need of an eagle diviner from Egypt.Footnote 4

The Hittites had specific bird watchers who acted as highly esteemed oracles. Different bird species were thought to possess different agencies and abilities to predict different events. Specific terminologies were used for different species by the bird watchers. Birds entering the view from the right, moving to the left, were interpreted as good omens, and, similarly, a bird moving across a river or creek diagonally was viewed positively. Birds moving from the left to the right were considered wicked omens. The prophesizing was a specific and complicated enquiry usually involving “several different birds, often of different species, each of which perform several fairly complicated motions.”Footnote 5 Careful records were kept of the outcome of the divinations. The records in Ashurbanipal’s library at Nineveh from the seventh century BCE in Assyria, for example, contained more than three hundred clay tablets devoted to divination, which equals several thousands of printed pages today.Footnote 6

Ancient Greece

In ancient Greece, birds were frequently used to predict the outcome of coming events. There are no less than thirty-five episodes in the Iliad where different birds bring forecasts about the future and, in particular, specific military missions and battles.Footnote 7 Most famous is the already cited scene occurring prior to the Achaeans launching their enormous fleet against Troy – modern-day Hisarlik. Before disembarking, several offerings were made to Zeus, requesting a prophecy about the coming war campaign. As an answer to these sacrifices, Zeus sent a blood-red serpent that climbed a plane tree and killed eight tender little nesting sparrows and their mother. This was interpreted by the special bird diviner Kalchas as an omen of how the war between the Achaeans and Troy would proceed:

As this snake has eaten the sparrow herself with her children, eight of them, and the mother was the ninth, who bore them, so for years as many as this shall we fight in this place and in the tenth year we shall take the city of the wide ways. So he spoke to us then; now all this is being accomplished.Footnote 8

Following Karin Johansson’s thought-provoking study The Birds in the Iliad, special emphasis was given to specific bird species, and it was usually the flight and behavior of the avian creatures that were the focus of the divinations. Special interest was paid to the flight path of birds, particularly birds of prey; appearing from the left or right was a bad omen or a good omen, respectively.Footnote 9 Fighting birds were always understood as a shattering outcome for upcoming battles.Footnote 10 Johansson underlines the vital role that birds played in people’s worldings:

The birds give them guidance, comfort, power, often fighting spirit. It is quite obvious that they fill needs among the people who need guidance, comfort and strife in difficult and dangerous times. Most of it circles around life and death.Footnote 11

Large birds of prey appearing in the Iliad, such as soaring eagles and vultures, often carried messages from prominent gods to equally important kings and war leaders. It is significant to note that the mentioned birds did not possess a semantic or symbolic value per se, but the behavior, agencies, and intra-action of a particular bird were key to its meaning and significance. This is clearly expressed in the Iliad. Divinations from birds were very seldom the outcome of rituals and offerings induced by mortals. Intra-acting birds seemed to possess an agency of their own; they suddenly appeared out of nowhere and acted in a peculiar way that demanded interpretation.Footnote 12 The ongoing scenario of a specific event changed after the intervention of a specific avian creature.

In book 8 of the Iliad, for instance, the battle at Troy is described, and Hector’s army are just about to wipe out the Achaeans. “The Achaians’ death-day was heaviest.”Footnote 13 One reason was that the morale of the Achaeans was waning. In despair, Agamemnon called out to his militia and pleaded to Zeus to save his army. The desperate king underlined that he had always been a good and generous king who made proper offerings to the gods; despite this, things seemed to be going the wrong way:

Father Zeus, is it one of our too strong kings you have stricken in this disaster now, and stripped him of his high honour? For I say that never did I pass by your fair-wrought altar in my benched ships when I came her on this desperate journey; but on all altars I burned the fat and the thighs of oxen in my desire to sack the strong-walled city of the Trojans. Still, Zeus, bring to pass at least this thing that I pray for. Let our men at least get clear and escape, and let not the Achaians be thus beaten down at the hand of the Trojans.Footnote 14

Agamemnon called out for a wonder. Immediately after his desperate plea, an eagle emerged in the sky carrying a fawn deer in its talons. The majestic avian creature – described as the most confident sign from the gods – dropped the animal in front of the temporary and portable altar that was dedicated to Zeus: “Straightway he sent down the most lordly of birds, an eagle, with a fawn, the young of the running deer, caught in his talons, who cast down the fawn beside Zeus’ splendid altar.”Footnote 15 This was collectively interpreted as a sign that Zeus had intervened and changed the outcome of the battle, a sign brought to the Achaeans from the intra-acting eagle. Their courage returned, with known results.Footnote 16

As Johansson notes, the ornithomanteia in the Iliad seemed to represent a common and shared knowledge and understanding of the unpredictable world among the Achaeans. More ambiguous bird intra-actions, such as the sparrow-eating serpent mentioned before, were harder to understand and demanded the interpretation of specific visionary specialists, like the renown seers Amphiaraus, Clytius, Iamus, Melampus, Mopsus, Tellias, Teiresias, or, in this case, Kalchas.

Other classical writers – such as Aeschylus, Xenophon, Sophocles, and Euripides – also describe the importance of bird divination.Footnote 17 Sometimes specific paraphernalia is mentioned. Sophocles and Euripides mentions an old bird-watching chair in Thebe that was famous for its capacity to give reliable prophecy, and sometimes certain places, such as Skiron in Athens, are stated as a gifted spot for bird divinations.

During the Classical Period in Greece, the divination practice had become an art form in itself, often described as a techne commenced from prominent gods like Apollo, Prometheus, or Zeus.Footnote 18 During this period, divination had become an institutionalized practice performed by professional ritual specialists – the manteis. The latter notion, mantis in singular, literally means “a human who is in a special mental state,” and it is usually translated as a “prophet,” “diviner,” “soothsayer,” or “seer.”Footnote 19 It was generally believed that these ritual specialists were chosen as envois by the gods who bestowed them with prophetic insights. Many times, the mantic knowledge was inherited by family members of known and admired seers – such as Melampus, Iamus (the son of Apollo), Clytius, and Tellias.Footnote 20 These legendary seers came to form profound lineages of ritual specialists stretching over several hundred years. Another method to become a seer was to enroll as an apprentice to someone with this ability. Some of the known manteis were born with a disability, touched by the gods, which empowered them to communicate with the deities. Many of the most famous seers, such as Teiresias and Euenius, traded their physical ability to see for gifts to see the unseen. The former was known for his ability to understand birdsongs, and according to some sources, Teiresas was bequeathed with this skill after Athena cleaned his ears.

Besides taking augury from birds, the manteis were also consulted to interpret powerful dreams and natural phenomena – such as thunder, lightning, earthquakes, comets, eclipses, et cetera – that were taken as omens and intra-actions from the gods. They also performed healing and purification rituals. Special messages from oracles – like the famous ones at Delphi, Dodona, and Thebes – also required readings, and special seers operated at these places. At shrines and other sacred places, seers also conducted ritual sacrifices and interpreted the entrails of slaughtered animals – extispicy – and read the burning of the entrails at altars dedicated to specific gods – empyromancy (Figure 8).Footnote 21

8 The famous seer Kalchas, here bestowed with wings as a token of his ability to communicate with the gods, taking extispicy from an animal liver. Bronze mirror from Vulci from the fourth century CE.

A special niche of the seers’ performance was associated with war campaigns, a ritualized practice that like no other was a matter of life and death. The most successful war leaders often had a symbiotic relationship with prominent seers. The famous relationship between Alexander the Great and Aristander is just one out of many.Footnote 22 A successful seer – such as Tisamenus of Elis, who was famous for winning five spectacular victories to Sparta – was admired and respected, even feared. The seers were both actively consulted before a battle through campground sacrifices – hiera – and through rituals conducted at the battle line just before or during a battle – sphagia.Footnote 23 The former included taking extispicy from war “victims,” especially from their livers. If no human nemeses were at hand, a sheep or goat could take its place. Slitting the victim’s throat and observing its movements and the flow of blood revealed the prophecy.Footnote 24 This was a dangerous living, and even a good seer had to be “good with the spear.” A single mistake could lead to the death of thousands. Many renowned seers, such as Amphiaraus, came to predict their own death. On the other hand, a prognostic and successful seer could earn a fortune – and eternal fame.Footnote 25

Bird divination plays a somewhat reduced role in later texts from ancient Greece from what is evident from reading the Iliad or Odyssey. Instead, we find more and more emphasis put on divination associated with sacrificial rituals at shrines and holy places devoted to specific gods. In later periods, the manteis also seem to lose some of their status, and Plato’s characterization of these “migrant charismatic specialists” in The Republic are an often quoted source of allusion:Footnote 26

Beggar priests (agurtai) and seers (manteis) frequent the doors of the rich and persuade them that they have obtained from the gods, through sacrifices and incantations, the power to heal them through pleasant rituals if some wrong was committed either by them or by their ancestors. And if someone wishes to bring ruin upon an enemy, with small expense he will be able to harm the just and unjust alike, since they have the ability through certain enchantments and binding spells to persuade the gods, as they say, to serve them.Footnote 27

That said, birds were still considered divine messengers, and this was particularly the case during war campaigns.Footnote 28 Some battle leaders even used avian creatures as deceptive paraphernalia to build morale and agitate the troops before a battle. All that was needed was a captured owl, which held special significance to the Achaean troops, that could be let loose just before the battle started.Footnote 29 The presence of the dazed nocturnal bird, mounting away on its wings over the armed forces, was collectively interpreted as a propitious omen from the gods – it was a good day to die.

The Romans

Nowhere in the ancient world was the divination of birds so institutionalized as it was in the Roman Empire. It was an austere state business. The reason for this was simple:

The uncertainties of the present and the capriciousness of politics in Rome, along with the absence of any concrete or realistic expectations of what the future might bring, provided fertile soil for seers and soothsayers, irrational longing for a savior, and predictions of a new and blessed age.Footnote 30

Birds were considered the prime envois for what the future might harness. As so many other cultural traits, much of the knowledge about birds as divine messengers seemed to stem from Greece. Pliny the Younger mentions specific Tiresias, the seer of Thebe, as the inventor of this practice, but the influence from Etruscan culture with their renowned netsvis diviners cannot be overlooked. The netsvis generally made use of the gastric contents from birds and other animals – extispicy – to explore the past and to predict the future, a phenomenon that we shall return to shortly.Footnote 31

In Rome, every major event and most minor events that were conducted in the name of the state – such as elections, the appointment and inauguration of official posts, the passing of new laws, war campaigns, and more – had to be approved by the gods. The most consulted gods were Jupiter and Mars, and most of the time their judgments were mediated through intra-acting birds. Ritual specialists, the augures, which translates to “one that looks at birds” or “bird viewers,” read the signs from birds – vitia. These specialists were divided into two kinds of seers: the augur, who listened to what the birds said, and the auspex, who watched what they did and took omens from their entrails.Footnote 32

At first, this institution contained four augurs gathered from the patricians, but after 300 BCE and the law of Lex Ogulnia, the number increased to nine. Five of these posts were assigned to plebeians. The foremost duty of the augures was to interpret the signs from the gods that were either good (auspicious) or bad (inauspicious), which were then mediated by the magistrates who decided if they wanted to follow the will of the gods, or not. Bird divinations were a predicament for the political life. The augures kept records of past signs; the rituals, prayers, and procedures to follow; their interpretations; and the outcome of earlier divinations.Footnote 33

There were five different auspices in the Roman Empire, two of which explicitly considered birds:Footnote 34

Ex caelo, meaning “from the sky,” such as thunder and lightning, which were believed to be a sign from Jupiter, or other phenomena appearing in the sky

Ex avibus, meaning “from birds,” usually was the song or flight of birds over the sky that was interpreted, but their other behaviors were also important

Ex tripudiis, meaning “from the dance,” where signs were interpreted from the movement of domestic birds that were fed

Ex quadrupedibus, meaning “from quadrupeds” – i.e., auspices from animals with four legs, such as strange behavior from horses, foxes, wolfs, or dogs

Ex diris, meaning “from portents,” which dealt with the interpretation of all other unpredictable abnormal phenomena that occur around us.

Next to thunder and lightning sent by Jupiter, the ex avibus were the most important omens. Following Cicero’s De Divinatione, the messages sent by the gods through birds were divided into two types, Oscines (talkers) and Alites (flyers).Footnote 35 The former were grounded on the songs of birds – where ravens, crows, owls, and hens were the most important species – and the latter were built on birds’ flight over the sky. For the Alites, the behavior of eagles and vultures seemed to be most important, but other strangely intra-acting birds were considered as well.Footnote 36 Besides the movement of birds over the sky, altered songs, and unusual behavior, other specific circumstances were also important for divination: the hour of the day or the time of year when a phenomenon occurred, weather and sky spectacles that were connected to specific birds, and so forth.

Worth noting in this context is that in contrast to the Greek and earlier textual accounts, Roman augures preferred to interpret birds entering from the left as a good sign, and vice versa. The signs of the gods could either be sought after, a so-called impetrative sign, or occurred more spontaneously, an oblative sign. The former sign followed after a request from some public leaders and after an augur conducted offerings to discern the will of the gods before an important decision. The oblative sign, such as an abnormal intra-acting bird or group of birds, were thought to be offered directly by the gods without any requests, and many times these divinations were considered to be more powerful and important to consider.

According to Cicero, the auspices ex tripudiis – meaning dance of the birds – concerned a large group of species and behaviors, but it more frequently came to be associated with military campaigns and the behavior of chickens.Footnote 37 A specific interpreter, the pullarius, kept the birds in cages during military campaigns. On command, the chicken were let out of their cages and fed, and based on their behavior, the outcome of the mission was predicted. It was a good sign if the chickens were calm and happy, especially if they ate with appetite and dropped some crumbs on the ground, but the opposite was the case if they were fearful, anxious, beating their wings, or tried to escape.

The auspices of ex quadrupedibus and ex diris usually only considered private personal issues and businesses, and it seldom or never concerned state affairs.

From our viewpoint, today it might be hard to understand the central role of bird divination in the Roman Empire, but it must be seen in light of Rome’s foundation myth. Central to this legend, we find a green woodpecker, which helped the wolf feed the twins Romulus and Remus, the legendary founders of Rome. Moreover, according to Plutarch, sitting on the Palatine Hill, Romulus and Remus quarreled about where the city of Rome should be built. Remus said it should be built on the Aventine Hill, which would be easy to fortify and defend, while Romulus wanted it to be situated on the Palatine. Both agreed to let the gods decide by conducting a ritual augury competition. Romulus won by spotting twelve vultures, twice as many as Remus.

Bird Watchers in North Europe?

There are very scant written sources that can enlighten us about the role of birds and bird divination in North Europe in prehistoric times. The Roman Publius Cornelius Tacitus’s (55–120) Germania, dated to late first century CE, is one of the oldest, most trusted, and most quoted sources. In chapter 10 of his book, Tacitus proclaims that the Germanic tribes north of Limes “attend to auspices and lots like no one else.” He also mentions that they “examine the calls and flights of birds,” but does not discuss when, where, how, or why this was done.Footnote 38 One reason for this seems to be that Tacitus was well acquainted with bird divinations from his own cultural context. His attention was instead turned to the practice of divinations from intra-acting horses:

Peculiar to that people, in contrast, is to try as well the portents and omens of horses: maintained at public expense in the groves and woods, they are white and untouched by any earthly task; when yoked to the sacred chariot, the priest and the king or leading man of the state escort them and note their neighs and snorts. To no other auspices is greater faith granted, not only among the common folk, but among the nobles and priests, for they see themselves as mere servants of the gods, but the horses as their intimates. There is also another way of observing auspices, which they use to forecast the outcome of serious wars. From the people with whom they are fighting they somehow seize a captive, and send him against a champion of their own countrymen, each with his native arms; the victory of the one or the other is received as a precedent.Footnote 39

Tacitus mentions the custom of Germanic tribes taking divination from horses and birds, and this is often used literally as a source of information by archaeologist dealing with Iron Age societies.Footnote 40 There are some intriguing finds of scarified horses in North Europe that suggest these animals were used in divination practices.Footnote 41 One of the most telling examples comes from Skedemosse on the island of Öland in Sweden.Footnote 42 This site, which mainly dates to the late Roman Iron Age and Migration Period, is known for its lavish finds of gold objects – like snake-head arm rings, finger rings, and denars – that have been sacrificed in the bog or shallow lake. The finds also include at least 318 iron spearheads, forty-four swords, fifty shields, thirty iron axes, and numerous bones originating from at least two cats, some deer, one wild boar, fifteen pigs, seven dogs, sixty sheep and/or goats, eighty cattle, and more than one hundred horses.Footnote 43 On top of this, at least thirty-eight humans have been sacrificed in Skedemosse, and many show traces of vicious and lethal violence.Footnote 44

In traditional societies, sacrificial rituals like those documented at Skedemosse are intimately linked to appeasing gods or other immaterial powers, and to bringing about divinations that predict the future.Footnote 45 It is therefore reasonable to give credit to Tacitus’s information. Norse mythology and Sagas support this conclusion where both birds and horses are used for divination.Footnote 46

The sacrifice of horses at Skedemosse is well attested in Iron Age research, and it is supported by written sources, the analyses of the bones, and from the depositional patterns at the site.Footnote 47 It is reasonable to interpret most of the finds from Skedemosse as offerings of appeasement to the gods or other immaterial powers in order to procure omens about the outcome of impending events. What is more seldom discussed in this context is that there are also a lot of bird bones found at Skedemosse. In fact, twenty-nine different bird species were documented in the first analyses of the bones: starling (5 identified bones), white wagtail (1), song thrush (2), herring gull (1), great black-backed gull (1), common tern (1), snipe (8), curlew (1), coot (6), spotted crake (5), water rail (3), crane (1), domestic fowl (Gallus gallus, 6), capercailzie (13), hen harrier (1), white-tailed eagle (50), greylag goose (2), goosander (15), red-breasted merganser (8), goldeneye (14), tufted duck (8), garganey (3), teal (20), pintail (4), mallard (98), bittern (2), cormorant (13), great crested grebe (13), and horned grebe (1).Footnote 48 New finds and a reassessment of the bone material ten years after the first analysis added ten additional bird species: raven (1 identified bone), jay (1), short-eared owl (1), ring dove (1), black guillemot (1), greenshank (1), golden plover (1), lapwing (1), shoveler (2), and red-throated diver (1).Footnote 49

Many of these birds seem to be found out of their natural habitat, such as the capercailzie, domestic fowl, and goose, and possibly also the numerous and puzzling bones of white-tailed eagles.Footnote 50 Despite this, Iron Age scholars have not subjected the bird finds from Skedemosse to any further analyses or interpretations. The reason for this is that the zoologist who analyzed the bone material, the legendary Johaness Lepiksaar (1907–2005), who is acknowledged as one of the leading North European avian experts during the last century, thought that the bird bones from Skedemosse “had a natural origin.”Footnote 51 Lepiksaar noted, “the manner in which many of these bones has been cut into pieces was reminiscent primarily of the remains of bones found in the prey and pellets of raptorial birds.” Some even had “marks of the claws of a raptorial bird,” and he writes: “No clear traces of cutting or chopping by implements used by man can be discerned in these bones.” Lepiksaar’s conclusion was that the bird bones “would seem to have a natural origin,” meaning that they should not be considered with the other bones and materialities that had been deposited and sacrificed at Skedemosse.Footnote 52

Later scholars have followed Lepiksaar’s word.Footnote 53 It must therefore be considered unwise – or even foolish – for an amateur zoologist like myself to contest the interpretation of one of the most respected and recognized bird specialists of North Europe. However, Lepiksaar’s analyses must been seen in the light of the modernistic paradigm he worked under – naturalism – that cherished a flawless split between “nature” and “culture.” Seen from the agential realist perspectivism, a moor or shallow lake such as Skedemosse would be a perfect setting for any birder to observe and take omens from avian oscines or alites (read “talkers” or “flyers”). The compelling agencies of birds consuming sacrificed bodies of both human and nonhuman beings must have had great significance for those who conducted these ritualized practices at Skedemosse. Maybe the birds acted as envoys carrying the sacrificed bodies to the gods? Maybe these birds were believed to carry – or even taking – omens themselves? Maybe it was these or similar intra-actions of avian creatures that made a place suitable for sacrificial rituals in the first place? The moor or shallow lake, trembling with life and sound, is an inspiring and a persuasive place on its own, a place that is often understood as an opening to the netherworld, the Land of the Dead. Was this a place where human and nonhuman beings intra-acted, conveying memos from the divine and the undead, a place where human and nonhuman beings reenacted and unfolded their worldings?

There are alternative interpretations to be offered to the bird bones from Skedemosse that pull in similar directions. Could it be that Lepiksaar’s analyzed traces from auguries from the entrails of raptorial birds – extispicy? The presence of “marks of the claws of a raptorial bird” on some of the bird bones, as well as the absence of any concrete traces of “cutting or shopping by implements used by man” could both be an outcome of careful and watchful auspexes who took omens from the entrails of avian creatures. This interpretation could even gain some support from archaeology, for many of the bird bones in question originated from what the excavation team defined as “bone concentrations,” what a zooarchaeologist of today would define as “distinct associated bone groups.”Footnote 54 In this context this notion means that the bird bones in question were found in situ mixed together with other bones that without doubt are to be considered as traces of offerings and/or divination rituals.Footnote 55 To be specific, twenty-one out of the 105 bone concentrations that were documented at Skedemosse, equaling 20 percent of the assemblage, contained bones from one or several bird species.Footnote 56 To separate these bones from their specific find contexts and assign avian bones a different interpretation from other animal bones seems illogical. All in all, this seems to give further evidence to Tacitus statement that Germanic Iron Age tribes north of Limes took omens from birds.Footnote 57

Bird Watchers in the Bronze Age?

It is very unusual that Tacitus is used as a source of information for Bronze Age studies in North Europe. One reason for this is that researchers have been inclined to use Iron Age sources imposed on Bronze Age contexts.Footnote 58 It is also an outcome of the circumstance that very few scholars cover both the Bronze and Iron Age in their research. Considering the prominent role of the horse in Bronze Age cosmology in North Europe and the obvious presence of horse sacrifices during this era, for example at the Röekillorna Spring in Scania, it might be worth reconsidering this cautious attitude.Footnote 59

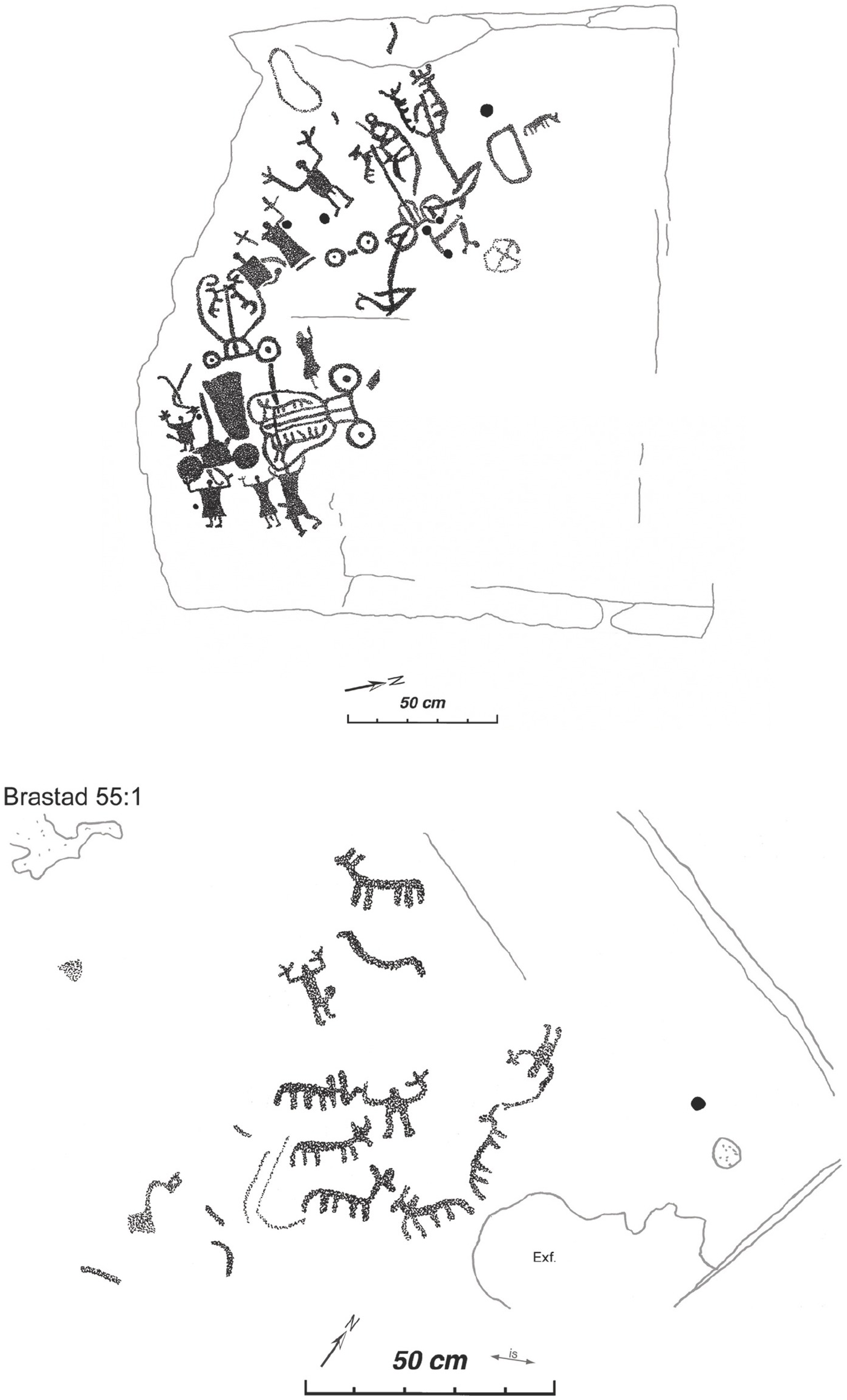

A reason for reappraising Tacitus’s validity in Bronze Age studies is that we find horse figures in rock art from this epoch that appear to recall his wording quite literally. Here I think about engraved wagon figures pulled by horses that are surrounded by anthropomorphic figures with raised hands: “when yoked to the sacred chariot, the priest and the king or leading man of the state escort them and note their neighs and snorts” (Figure 9).Footnote 60 When these figures were newly pecked, they would shine as white as quartz, a distinctive feature of the sacred horses mentioned by Tacitus. Similar depictions are found fairly frequently, as are ritual deposits of bronze horse gear from LBA that adorn wagons that were contemporary with the depicted wagon scenes (see Plate 5).Footnote 61 This provides some sustenance for Tacitus account.

9 Details of the panels Brastad 18 (above) and Brastad 55 (below) in northern Bohuslän showing horse and human intra-actions. Documentation made by Tommy Andersson and Andreas Toreld.

Other rock art panels seem to depict intra-acting human and horse figures that could also be interpreted in line with Tacitus. One example, among many, is the panel Brastad 55 in northern Bohuslän in Sweden, where three pecked human figures with raised arms watch several horse figures (Figure 9). The latter gesture, known as adorants by rock art scholars in this part of the world, is usually interpreted as a pose for worship.Footnote 62 With Tacitus’s notice in fresh memory, it might be plausible to interpret these engravings as depictions of ritual specialists taking auspices from horses. Supportive of this interpretation is the common trait of finding horse engravings depicted with open mouths, which might signify their ability to communicate with humans.Footnote 63 Other rock art panels show similar depictions and scenarios.Footnote 64

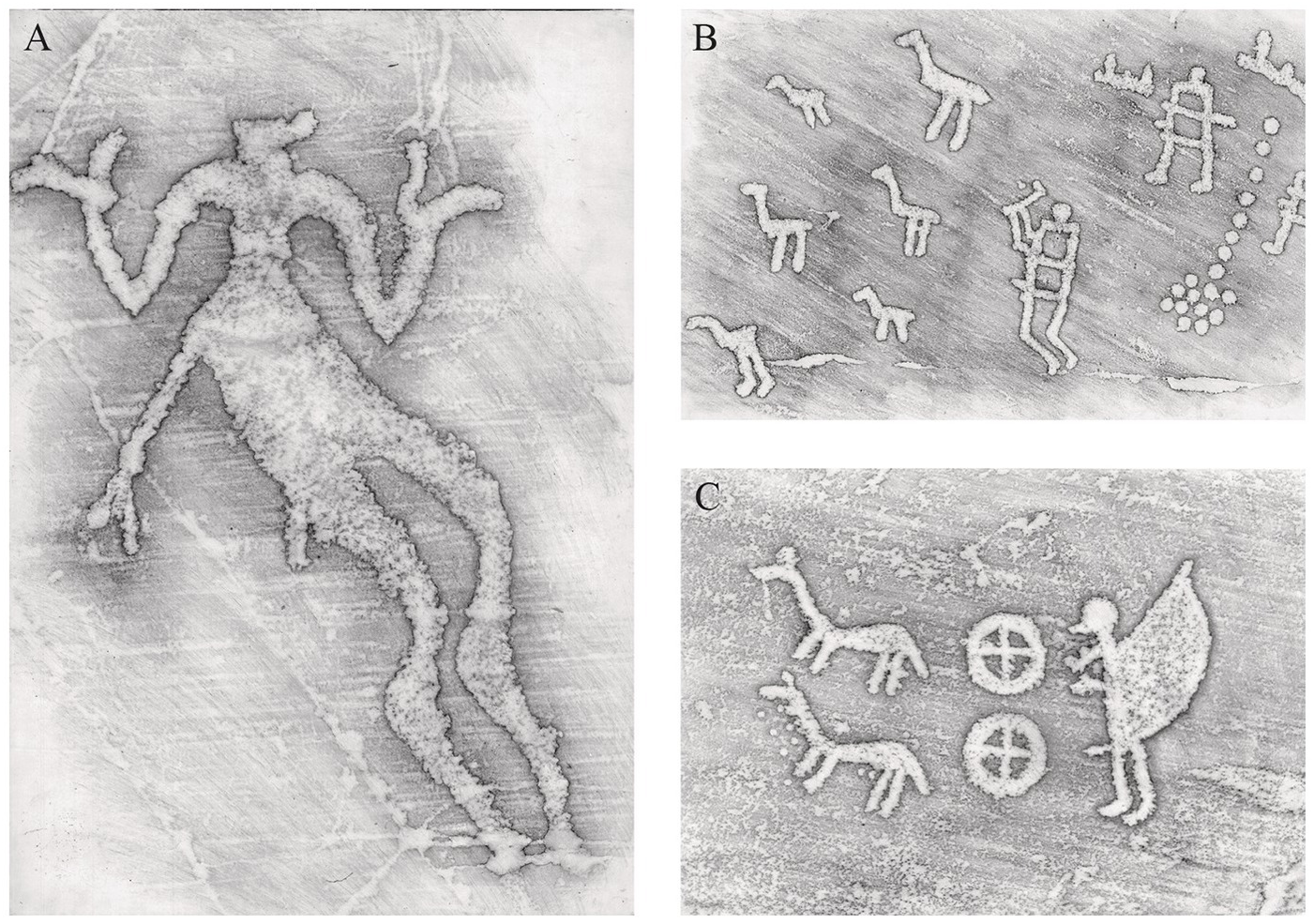

Looking at the human figures on the Brastad panel again (Figure 9), we see that some of them are depicted with forked hands. Some rock art scholars have interpreted this trait as a “holy sign,” but it could very well be interpreted as a human holding a bird. This is a trait that is found on other panels as well – for example, on the famous rock art panel from Järrestad in Scania, where a “dancing” anthropomorphic figure seems to be depicted with birds sitting on its hands (Figure 10).Footnote 65

10 Frottages made by Dietrich Evers showing an anthropomorphic figure with an avian creature sitting on its hand from Järrestad 13 in Scania (left); detail from Tanum 9 (above right), notice the ship- and razor-like form of the body and head of some bird figures, and notice that one of the birds seems to be depicted with human feet; and an example of an engraved winged anthropomorph with a beak (below right), this one is from Ånneröd, Skee 625.

Depicted scenes with intra-action between human and birds in North Europe are rare but not unseen. On the central part of the panel Tanum 9 in northern Bohuslän, for instance, we see some anthropomorphic figures depicted close to bird figures (Figure 10). A similar scene occurs on the famous Hemsta panel in Uppland, Boglösa 131 (Figure 11).Footnote 66 Judging from their long legs, most of the depicted birds on Tanum 9 and Boglösa 131 are likely some kind of large wader, usually interpreted as common cranes. Undoubtedly, the stone medium makes it difficult to distinguish certain bird species from each other, so they could also be storks or grey herons that are depicted (Figures 10 and 11).

11 Above, the Medbo panel, Brastad 109 in Bohuslän. Note the birds in the tree, and the possible corvid flying over the boat. Below, a twitcher from Boglösa 131, the Hemsta panel in Uppland. Documentation made Tommy Andersson and Andreas Toreld (Brastad 109) and Sven-Gunnar Broström and Kenneth Ihrestam (Boglösa 131).

One of the engraved anthropomophs on the Tanum 9 panel has a raised phallus and carries an axe or staff in his hand (Figure 10). This posture is often found in rock art scenes when warriors travel on boats, when they are walking in procession, or when they are engaged in duels – scenes that are associated with ritualized practices in connection to maritime interaction and structured violence. The twitcher on the Hemsta panel has raised arms and a raised phallus and can be characterized as an adorant or, as I prefer to interpret this scene, as a ritual specialist taking auspices from birds (Figure 11).Footnote 67

The similarity between the depicted horse and bird watchers is reinforced through bird depictions with open beaks, which could be taken as a sign that they were able to communicate with humans through their ability to sing or speak (Figure 11), what were known as “talkers” or oscines in Rome.Footnote 68 From these short examples, enough indication has been provided to suggest a reappraisal of Tacitus as an ethnographic source and to rethink the possibilities that bird divinations could have deep cultural roots in North Europe.

The rest of this book is dedicated to Bronze Age avian creatures in North Europe. A chief aim of the study is to explore the multispecies relational intra-action between humans and birds. For example, is it possible to find any traces of bird divination in the archaeological record? And if so, how should it be interpreted? In what context are humans intra-acting with birds, and, perhaps harder to grasp, how were birds intra-acting with humans?

To be able to answer these and related questions, we must first learn more about how birds feature in the archaeological record. The goal with this book is thus becoming evident: to present a broader picture of the role of avian creatures in Bronze Age worldings in North Europe. That said, the themes that I wish to explore in this book will start to unfold with a revisit to one of the most famous and iconic Bronze Age burials from this part of the world – the Hivdegård burial, an inexplicable burial dated to MBA III.