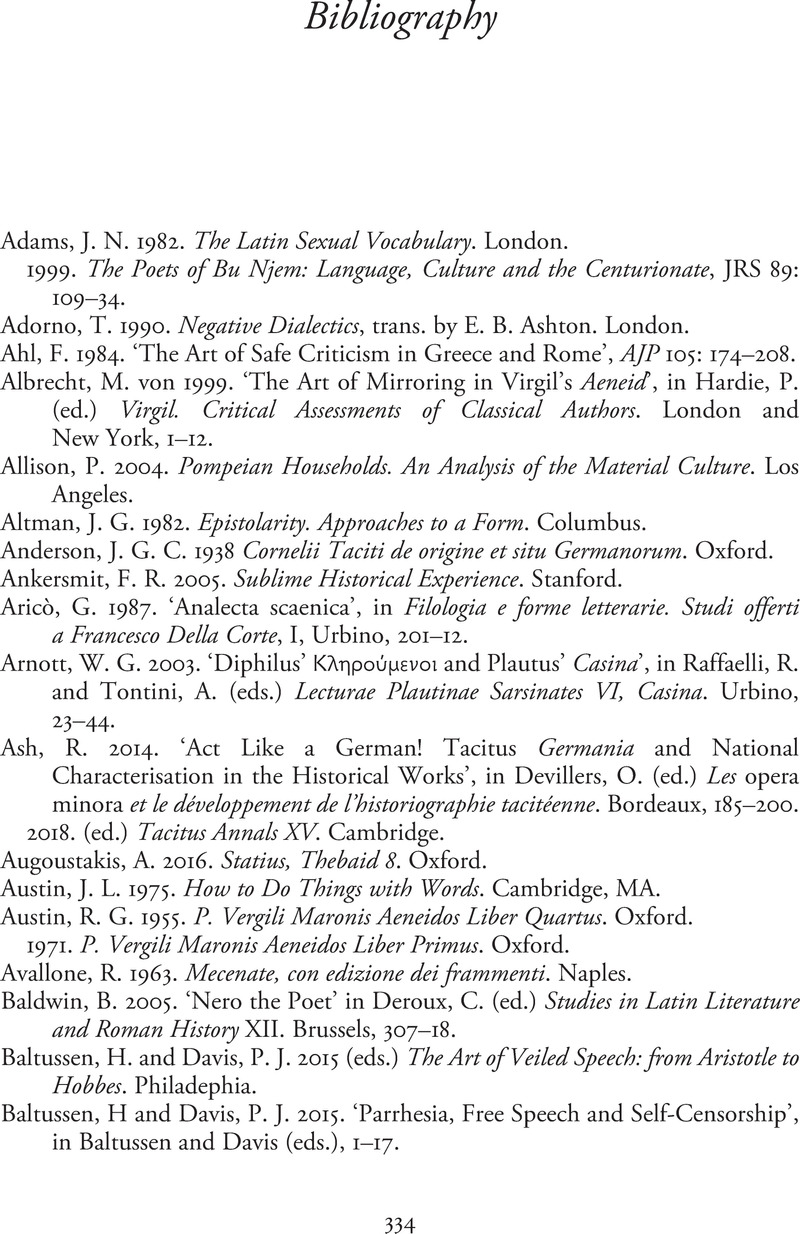

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 September 2021

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Unspoken RomeAbsence in Latin Literature and its Reception, pp. 334 - 363Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2021