22 - Wilhelm Rettich

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 09 May 2024

Summary

Wilhelm Rettich belonged to the generation whose life and work were deeply affected by both the First and Second World Wars. Captivity, persecution, concealment and loss scarred his life. In 1933, he emigrated to the Netherlands, where he survived the war in hiding. Rettich worked a fair amount for the radio, a young and progressive medium at that time. Although he became a Dutch citizen after the war, he returned to Germany in 1964.

He was born in Leipzig on 3 July 1892, the son of Isidor Rettich, a merchant, and Rosa Idelsohn. His parents wanted him to become a doctor, but he knew early on that music was his destiny. His mother came from a musical family and gave him his first piano lessons. At seventeen he studied composition with Max Reger at the Leipzig Conservatoire. He worked as an assistant répétiteur at the Leipzig Opera and as a conductor at the Stadttheater in Wilhelmshafen, a coastal town in Lower Saxony.

Rettich's musical career was interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War. He was called up to the army, serving as first clarinettist in an infantry band, but was soon conscripted to fight on the Russian front. In September 1914 he ended up as a prisoner in various Siberian camps. There he organised an orchestra and they made their own instruments. During his captivity he composed the one-act opera König Tod (‘King Death’) on scraps of paper, based on a fairytale written by a fellow prisoner, Franz Lestan. The work was premiered in 1928 in Stettin (now Sczcecin in north-western Poland), with Rettich conducting.

After the Russian Revolution in October 1917, he spent several years in Chita, a city in south-eastern Siberia, to the east of Lake Baikal and to the north of north-eastern Mongolia. To make a living he taught piano, particularly to refugees from St Petersburg and Moscow. He spoke Russian fluently and he composed songs set to Russian poems, by Lermontov, among others. In an interview in 1972, he recalled this period, which was relatively happy despite the many epidemics.

He finally returned to Leipzig in 1920, after having worked in Shanghai, Trieste and Vienna in the meantime.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

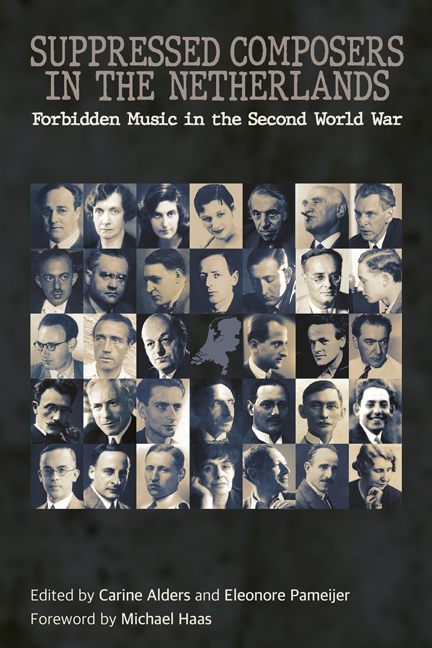

- Suppressed Composers in the NetherlandsForbidden Music in the Second World War, pp. 209 - 216Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2024