1 - Soho

London’s Gilded Gutter

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 05 December 2019

Summary

As a place that ‘plays to all the senses’,2 Soho has, throughout its history, been something of an abject space, maintaining a long-standing appeal as simultaneously alluring and threatening, exploiting many of those who work and consume there, while at the same time carefully nurturing its reputation as a place of bohemian indulgence, offering a warm embrace and a sense of belonging in the heart of an otherwise relatively anonymous urban environment. In his Foreword to Bernie Katz’s book Soho Society, Stephen Fry emphasizes this, highlighting how the area has always offered ‘outsiders’ a chance to be themselves: ‘Soho’s public face of drugs, prostitution and seedy Bohemia … has always hidden a private soul of family, neighbourhood, kindness, warmth and connection, and those qualities shine through doggedly.’ Yet Soho also has an enduring reputation for violence and exploitation.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

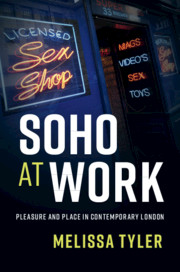

- Soho at WorkPleasure and Place in Contemporary London, pp. 15 - 46Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019