The Taste of Food in Hell: Cognition and the Buried Myth of Tantalus in Early Modern English Texts

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 January 2023

Summary

In Seneca’s Thyestes (c. 62 CE), the Ghost of Tantalus poses a question:

peius inuentum est siti

arente in undis aliquid et peius fame

hiante semper?

(has something been devised that’s worse than parching thirst amid the waves, and worse than gaping forever in hunger?)

Tantalus is doomed to spend eternity starved and parched, grasping at elusive fruits and water. The Fury who has raised his ghost from the underworld promises (in anticipation of the play’s conclusion, where Thyestes unwittingly eats his own children) events so terrible that they will ironically reverse Tantalus’s stricken situation: ‘I’ve planned a feast even you will flee from’ (‘inueni dapes/ quas ipse fugeres’). The play Thyestes not only poses but also answers Tantalus’s question: a father cannibalising his own children is something worse than eternal hunger and thirst. Several early modern authors, however, were not satisfied with this. They took up Tantalus’s question like a dare and competitively explored ever more terrible answers. The three texts I examine in this essay – Christopher Marlowe’s Tamburlaine the Great (first performed 1587), Thomas Dekker’s If It Be Not Good, The Diuel Is In It (first performed 1611), and John Milton’s Paradise Lost ([1667], 1674) – rise to this challenge with explorations of multisensory triggers and ensouled punishments. Without explicit mention of Tantalus, all three authors choose to present versions of his punishment, drawing not only on classical mythology but also ideas from Abrahamic religions. They employ a range of methods, including tableaux, dialogue, stagecraft, and amphibolous poetic descriptions, to present torments that involve but also exceed the pangs of eternal hunger and thirst.

Thomas Kyd’s play The Spanish Tragedy (1587) was inspired by Thyestes, perhaps via Jasper Heywood’s 1560 translation. Kyd mirrors the Senecan dialogue between Tantalus and the Fury when he has the Ghost of Andrea describe hell to Revenge, and Revenge promise lavishly bloody vengeance. Here, the Senecan augmentation of Tantalus’s punishment has been submerged within a lengthy hypotyposis of a hell,

Where Vsurers are choakt with melting golde,

And wantons are imbraste with ougly snakes:

And murderers grone with neuer killing wounds,

And periurde wights scalded in boyling lead.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

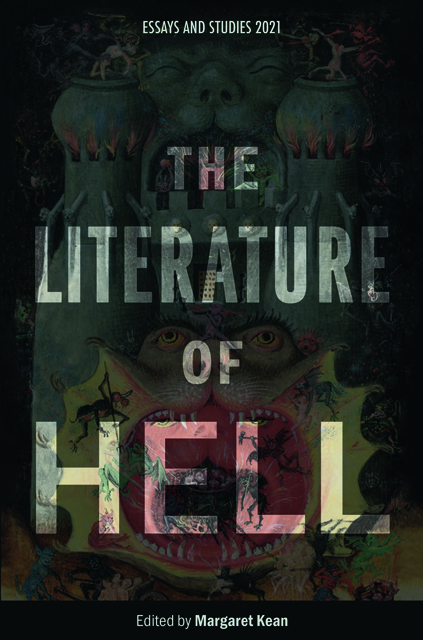

- The Literature of Hell , pp. 77 - 102Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2021