Book contents

- John Calvin in Context

- John Calvin in Context

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I France and Its Influence

- Part II Switzerland, Southern Germany, and Geneva

- Part III Empire and Society

- Part IV The Religious Question

- Part V Calvin’s Influences

- Part VI Calvin’s Reception

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

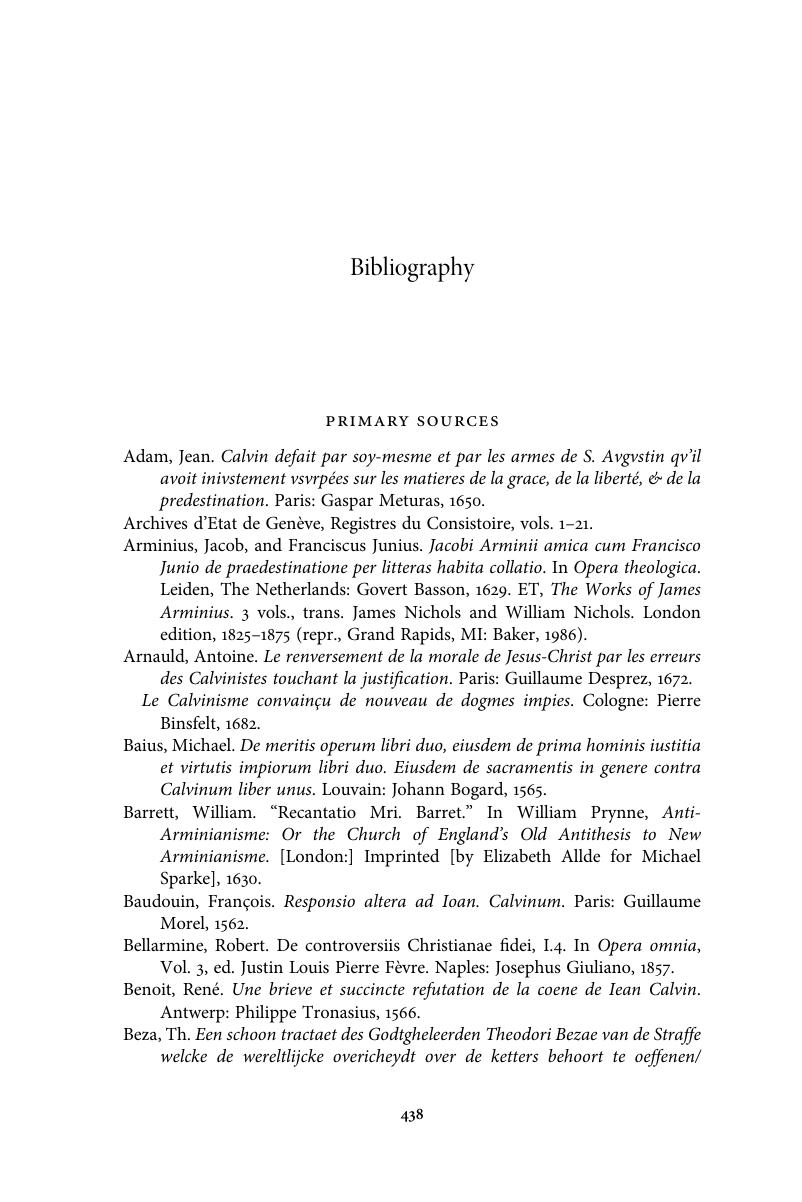

Bibliography

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 14 November 2019

- John Calvin in Context

- John Calvin in Context

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- Part I France and Its Influence

- Part II Switzerland, Southern Germany, and Geneva

- Part III Empire and Society

- Part IV The Religious Question

- Part V Calvin’s Influences

- Part VI Calvin’s Reception

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

- References

Summary

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- John Calvin in Context , pp. 438 - 473Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2019