9 - Temporal Perspectives in Scriabin’s LateMusic

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 07 October 2022

Summary

It is widely acknowledged that Scriabin's music,particularly his ‘atonal’ period, has mainly beenstudied with regard to pitch organisation, while aninvestigation of temporal structures has receivedless attention. Perhaps this is not by chance. Theanalytical tools that deal with the new tonalstructures – born at the turn of the century – areby now well tested, while it may be more challengingto manage the temporal axis. And yet, just ashappened with respect to pitch structure, with theentry into the atonal universe – between the latenineteenth century and the early twentieth – theorder of time underwent an extraordinary change.Linear and forward-projected time, which hadcharacterised music in the eighteenth and nineteenthcenturies, underwent a transformation: like allreality, temporality lost its ontological fixity,disintegrating into a multiplicity of flows.

It is especially in the treatment of large-scale formthat this new orientation becomes evident, from theRomantic era onwards. Double or multipletemporality, mimetic and diegetic time, inner andouter time, progressive and lyrical time, and publicand private time are some of the numerous binarypairs that have recently been used to describe thecomplexity of temporal experience in music. In thisrespect, the turn of the century saw greattransformations: a kind of ontological multiplicity,concerning all fields of knowledge, in apulverisation of perspectives, now makes the worldmore uncertain. Each vision embraces only part ofthe horizon, and it is only in the perceivingsubject that a reunification occurs, albeitprovisional and partial.

One feature of this cultural phase, which draws heavilyon Nietzsche, is the idea that time no longer hasprojective properties: the meaning of a time celldoes not come from a more general chain containingit but is to be sought in itself. The instant is thenode of a crossroads, according to a famousNietzschean image, which has behind it one eternityand after it another. That instant, therefore, is nolonger a link in a chain to which it is connected bya necessary order; placed at the crossroads of twoeternities that repeat themselves, it too becomes aneternity. In other words, the focus of the temporaldimension does not lie on the hypothesis of aprogressive and organic succession; rather, theinstant itself is enhanced and dilated, allowing thephilosophical notion of duration to emerge.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

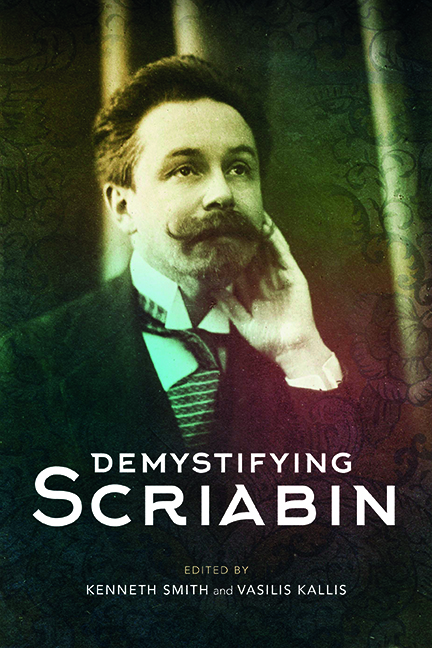

- Demystifying Scriabin , pp. 158 - 177Publisher: Boydell & BrewerPrint publication year: 2022