Book contents

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword (David Langslow)

- PART I THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- PART II EARLY LATIN

- PART III CLASSICAL LATIN

- PART IV EARLY PRINCIPATE

- PART V LATE LATIN

- 22 Late sparsa collegimus: the influence of sources on the language of Jordanes

- 23 The tale of Frodebert's tail

- 24 Colloquial Latin in the Insular Latin scholastic colloquia?

- 25 Conversations in Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica

- Abbreviations

- References

- Subject index

- Index verborum

- Index locorum

23 - The tale of Frodebert's tail

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 April 2011

- Frontmatter

- Contents

- List of contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Foreword (David Langslow)

- PART I THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

- PART II EARLY LATIN

- PART III CLASSICAL LATIN

- PART IV EARLY PRINCIPATE

- PART V LATE LATIN

- 22 Late sparsa collegimus: the influence of sources on the language of Jordanes

- 23 The tale of Frodebert's tail

- 24 Colloquial Latin in the Insular Latin scholastic colloquia?

- 25 Conversations in Bede's Historia Ecclesiastica

- Abbreviations

- References

- Subject index

- Index verborum

- Index locorum

Summary

Das ist das wahrste Denkmal der ganzen Merowingerzeit.

B. Krusch (Winterfeld 1905: 60)ne respondeas stulto iuxta stultitiam suam ne efficiaris ei similis

responde stulto iuxta stultitiam suam ne sibi sapiens esse videatur

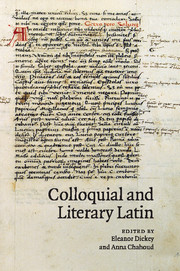

(Proverbs 26:4–5)What is known about how a text is transmitted affects the evaluation of its content. And evaluation and classification of content in turn affect the interpretation of words and language. Literary historians must decide what it is they have in front of them using internal and, where available, external evidence too. Lexicon, syntax, metrics, topoi, generic markers, and more, all go into the taxonomic decision. And once a work has a place in some sort of scholarly taxonomy it may then be used (or abused). A text's nature and classification may also be interpreted in widely divergent ways by scholars who never engage each others' views. Near the end of the long period this volume covers (third century bc – eighth century ad) the Letters of Frodebert and Importunus, texts that some regard as serious documents and others as obvious parodies, provide a case study of such a problem. Commentary on them can easily expand to book-length. My concern here will be to pinpoint the nature of a late text of controversial content, genre and characteristics (learned/vulgar, literary/colloquial, ecclesiastical/secular, written/oral, Latin/Romance). My discussion will begin with the mise en scène and continue with series of limited textual and interpretative problems showing how arguments even about small philological points affect much broader assumptions about what these texts are.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Colloquial and Literary Latin , pp. 376 - 405Publisher: Cambridge University PressPrint publication year: 2010

- 4

- Cited by