Introduction: The Lawn is Singing

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 29 October 2019

Summary

There is a way in which the dryness of the winter veld, when the sun is very harsh and the grass is bleached very white, or else is very black from veld fires, corresponds to the tonal range of a white sheet of paper and charcoal and charcoal dust – in a way more immediately even than oil paint. There was a way in which the winter veld fires, in which the grass is burned to black stubble, made drawings of themselves. You could rub a sheet of paper across the landscape itself, and you would come up with a charcoal drawing.

— William Kentridge, ‘Meeting the World Halfway: A Johannesburg Biography’William Kentridge (2010) observes that for much of his childhood in Johannesburg he felt that he ‘had been cheated of a landscape’. He explains that he wanted a landscape of ‘forests, of trees, of brooks’ but instead he had ‘dry veld, beyond the green gardens of the city’. The ‘veld’ is a particularly South African notion. Originally a Dutch word meaning ‘field’ or ‘countryside’, in Afrikaans it describes a field, pasture, plain, territory or ground, and in South African botany it is used to describe a set of vegetation found in southern Africa.

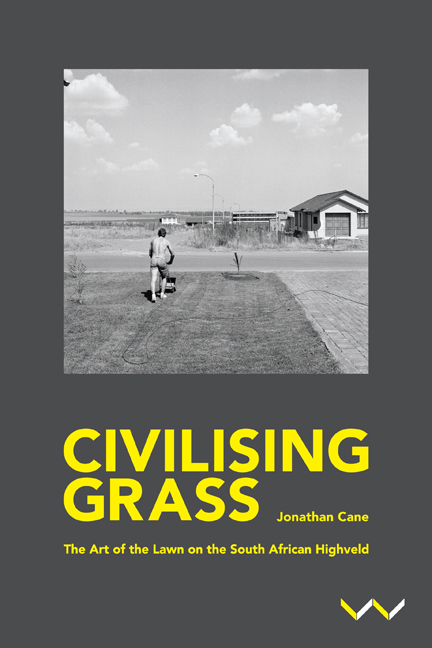

I felt this too when I was growing up in Johannesburg – without a landscape. I recall sitting in the back seat of my parents’ car watching fires burn across the winter veld, casting palls of smoke across the highways. I longed for green. I remember dreaming of planting lawns over the mine dumps and along the so-called green belts. The same fires would also burn the open grass veld next to our home, and the white men who owned homes in the suburb would beat the fire with sacks while my mother (and myself, when I had grown older) would spray water on the roof and lawns. Mostly, catastrophe was averted, but sometimes the fire would nick the lawn from over the precast concrete walls, scarring it black.

The lawn, consistently and perfectly mown, was a great joy to my father but also a cause for concern. On weekdays the gardeners – Laxton, after him Sam, then Benjamin and Hanock – would mow, fertilise, water, seed, spread compost and repair broken sprinklers. On weekends my shirtless father would mow his lawn.

- Type

- Chapter

- Information

- Civilising GrassThe Art of the Lawn on the South African Highveld, pp. 1 - 20Publisher: Wits University PressPrint publication year: 2019