3 Abortion, social movements, and mass media

Legalized abortion is a contentious issue in contemporary American politics. This was not always the case. Initially, abortion was a medical concern and physicians were the arbiters of its administration. This “medicalization” of abortion largely was the result of a campaign by physicians to professionalize medicine. Throughout most of the nineteenth century, there were no licensing laws regulating who could practice medicine. This, coupled with the lack of a traditional guild structure, meant that physicians had to compete directly with other medical sects (such as homeopaths) for patients. Physicians saw abortion as an issue through which they could distinguish themselves from other practitioners and push for industry regulation. They argued that their scientific-based training gave them superior knowledge regarding if and when a woman should have an abortion. The campaign was a success. All but “therapeutic” abortions were outlawed and licensed professionals were charged with deciding whether an abortion was performed (Luker Reference Luker1984; Mohr Reference Mohr1978).

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, physicians, activists, and clergy pushed state legislators to repeal abortion laws and expand the circumstances in which physicians could administer abortions, including in cases of rape, incest, and fetal deformity. These efforts were both successful and largely uncontroversial, in part because of how the abortion issue was framed. Advocates argued that the state should expand physicians’ authority regarding the medical circumstances in which an abortion could be administered; an approach that focused on medical practice rather than women’s rights (Burns Reference Burns2005; Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1991). However, the framework for understanding abortion changed in the 1960s as a result of two controversies that focused public attention on women’s authority in reproductive decision-making. The first case involved Sherri Finkbine, a teacher in the popular television series Romper Room, who sought an abortion in 1962 after learning that she had ingested a drug known to cause fetal deformity. Finkbine used her celebrity status and connections with journalists to raise public awareness regarding the issue. While Finkbine’s story generated a lot of press, the publicity scared hospital officials, who refused to give her an abortion. Finkbine traveled to Sweden for the procedure, where her physician informed her that the fetus was severely deformed and would not have survived outside of the womb (Luker Reference Luker1984). The rubella measles epidemic also served as a lightning rod for abortion controversy. When contracted by a pregnant woman, the disease could cause fetal malformations. After this link was made visible via the evening news, thousands of pregnant women who contracted the disease sought abortions.

These controversies provided a new framework for understanding the abortion issue – a woman’s right to choose whether she had an abortion – and spurred the growth of the pro-choice movement, which explicitly argued that women have a constitutionally protected right to an abortion. For instance, the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws (now known as NARAL Pro-Choice America) formed in 1969 and began organizing repeal campaigns countrywide. Likewise, dozens of grassroots groups emerged and used direct action tactics and street theatre to raise awareness regarding the importance of safe and legal abortion to women’s health (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1988). The controversies also highlighted how great the differences of opinion regarding legalized abortion were in America. Pro-life activists began organizing at the state level with the goal of protecting “unborn children.” The stage for the contemporary battle over abortion was set with two Supreme Court decisions decided on January 22, 1973. In Roe v. Wade the Court ruled that a woman has a constitutionally protected right to an abortion and that the state could not prohibit abortion during the first trimester or before viability. Viability was defined as the potential for a fetus to live outside of the womb in Doe v. Bolton.

Pro-choice advocates believed that the Supreme Court decisions resolved the issue. The composition of the pro-choice movement changed dramatically in the following decade. With abortion legal, there was limited need for direct action tactics and many of the radical organizations fell into obscurity. The movement became one of highly professional, national organizations with federated chapters throughout the United States (Staggenborg Reference Staggenborg1991). The movement between 1980 and 2000 predominantly consisted of groups that focused on research, shaping abortion policy, and ensuring access to reproductive services. The pro-life movement changed as well. Before 1973, the movement was largely spearheaded by the Catholic Church and pro-life groups that emerged locally in opposition to liberalizing abortion laws (Burns Reference Burns2005). However, in the wake of the decisions, pro-life advocates quickly mobilized inside and outside of government and began to challenge the new status quo. The movement developed organizations supporting three distinct foci: changing abortion policy, providing alternatives to abortion, and politicizing abortion clinics (through sidewalk counseling, prayer vigils, and direct action against clinics and its personnel). The compositions of the opposing movements, in short, are quite different.

The Supreme Court decisions not only influenced how the movements took shape, but also affected the contours of the battle. Most pro-life groups either looked for ways to limit legal abortion and its availability or to shut down abortion clinics. In both regards, the pro-choice movement found itself on the defensive. Here, I offer a brief overview of the political context in which the war over abortion has been waged. I focus on three different arenas – inside state legislatures and the Supreme Court, on Capitol Hill, and outside of abortion clinics – in which pro-choice and pro-life forces engage and discuss how they have tried to advance their interests since the Roe and Doe decisions. The purpose is not to provide a comprehensive account of abortion politics, but to give an overview of how the movements have worked to advance their causes so that the strategic decisions of particular groups can be understood within the broader context in which they were made. After this historical summary, I introduce the study and the organizations included in the research. I conclude the chapter by situating these organizations within a broader media context. I document the visibility of movement groups relative to other actors that are included in abortion coverage and highlight where the organizations included in this research rank relative to their allies over a twenty-year time frame. While media coverage does not reflect an organization’s media strategy, it provides a useful baseline for assessing an actor’s reputation in the media field as well as its use of mass media.

Abortion politics after Roe and Doe

There are three different arenas in which the battle over abortion has been fought: at the state level (state legislatures and the Supreme Court); at the federal level (on Capitol Hill); and on the streets (outside of abortion clinics). I discuss each and pay particular attention to how pro-choice and pro-life advocates have worked to advance their interests after Roe and Doe. This background is relevant to the discussion of organizational media strategy insofar as it provides the context in which groups make decisions about how to use mass media to forward their goals.

Restricting abortion within the state

After the Roe and Doe Supreme Court decisions, the pro-life movement introduced legislation that would restrict abortion access in states across the United States. The pro-choice movement was not nearly as organized as their opponents at the state level and found it difficult to stave off pro-life legislation. Therefore, after a state passed legislation restricting abortion, pro-choice groups challenged the constitutionality of the law in the judicial system. Generally speaking, pro-lifers advocated for legislation that acknowledged the rights of other parties (the parents of minor women and the fathers of the unborn child) in abortion decisions, discouraged women from getting abortions by making them more difficult to access, and recognized the life and rights of unborn babies. For instance, pro-life advocates successfully passed parental involvement laws for underage women seeking the abortion procedure, and most of these requirements have been affirmed by the Supreme Court. In Planned Parenthood of Kansas City v. Ashcroft (1983) the Court upheld a Missouri provision that required minors to obtain consent from a parent before obtaining an abortion. The ability of the state to restrict access to abortion was stipulated in a broader set of legal principles in Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey(1992), where the Supreme Court ruled that regulating abortion was constitutional as long as the requirements did not place an “undue burden” on a woman’s ability to obtain an abortion.1 As I discuss in the Afterword, testing what does or does not constitute an undue burden on women animates much of the pro-life movement’s contemporary legislative efforts.

Pro-lifers also successfully passed, and defended the constitutionality of, laws designed to discourage women from getting abortions and make the procedure less accessible. Informed consent laws, for example, mandate that women seeking an elective abortion undergo counseling and be given information about fetal development, the abortion procedure, their legal rights, and abortion alternatives.2 Additionally, pro-lifers passed dozens of TRAP (Targeted Regulation of Abortion Providers) laws that reduced the availability of the abortion by limiting where the procedure can be done and who can perform the procedure. Again, many of these provisions have withstood the scrutiny of the courts and, in fact, forty-four states and the District of Columbia currently have TRAP laws on their books.

The pro-life movement also made some headway in shifting the legislative emphasis away from women’s rights to those of the fetus. Initially, pro-lifers focused on passing fetal viability testing requirements before a woman could obtain an abortion. In Missouri, legislators passed a law declaring that life began at conception and that unborn children have “protectable interests.” The statute, among other things, prohibited government-employed doctors from aborting a fetus that they believed viable and required fetal viability testing after the twentieth week of pregnancy. The Supreme Court upheld the provision, noting that the state had the right to protect “potential life.” This spurred other states to pass viability legislation as well. As of 2014, twenty-one states have laws that prohibit abortion if the fetus is viable, except in cases of life or health endangerment of the woman.

The battle over abortion on Capitol Hill

The Roe and Doe decisions made the abortion issue a political one. This politicization, and eventual partisanship on abortion, began in the 1980 election when Ronald Reagan inserted a pro-life position into the Republican platform. While Reagan believed in the pro-life plank, he also saw the potential to draw evangelicals away from the Democratic Party; a constituency that Jimmy Carter made visible during his presidential bid. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, the abortion issue became ingrained in party politics with Democrats favoring legal abortion and Republicans opposing it. Not surprisingly, the makeup of Congress affects the number of allies a given bill has and whether it comes to fruition. Although activists and legislators often work together crafting policy proposals, a relatively small number of bills get congressional attention and an up-down vote. Here, I briefly discuss some of the most significant policy proposals advanced by pro-life and pro-choice advocates since the Roe and Doe decisions.

The pro-life movement initiated two federal challenges on abortion. First, they questioned the use of tax dollars to pay for a procedure that many citizens vehemently opposed. Despite pro-choice arguments that such restrictions discriminated against poor women and women of color (Sillman et al. Reference Silliman, Fried, Ross and Gutierrez2004), this line of attack proved successful. In 1976, the Hyde amendment passed and prohibited the use of federal funds for the abortion procedure. In 1979, funding restrictions were extended to military health care coverage, banning the use of federal funds for abortion services at overseas military hospitals. In 1995, pro-lifers passed a Department of Defense appropriations bill that restricted women from obtaining privately funded abortion services at overseas military facilities except in cases of rape or incest.

Second, pro-lifers tried to overturn the Roe decision. However, as I discuss in the next chapter, there was not a consensus among groups regarding whether pro-life proposals should include an exception to save the life of the woman. While mainstream groups argued that an exception was necessary and supported the passage of the Human Life Amendment, which would reverse Roe and prevent states from making abortion legal at a later date, more radical pro-lifers regarded the exception an unacceptable compromise. Other pro-life advocates, who also advocated for states’ rights to make policy decisions, argued that the passage of a Constitutional Amendment was unlikely and advocated for the Human Life Bill, which declared that unborn humans were legal persons and restricted the power of lower federal courts to interfere with laws restricting abortion passed by the state. All of these efforts ultimately failed.

More recently, an important win for the pro-life movement has been the debate over partial-birth abortion; a phrase that refers to a particular abortion procedure (medically known as the intact dilation and extraction procedure) performed late in a woman’s pregnancy. Pro-lifers coined the term partial-birth abortion in 1995 and launched a national campaign calling for its ban. Congress answered the call and passed three bans on the procedure. The first two were vetoed by President Clinton, who refused to sign the bill because it did not include an exception to protect a woman’s health, in 1996 and 1997. President George W. Bush, Jr., however, signed the Federal Abortion Ban into law in 2003. The Supreme Court upheld the law in Gonzales v. Carhart (2006), ruling that an exception to protect women’s health was not necessary because there were other medical procedures available.

The pro-choice movement has introduced its share of legislation. Once it became clear that the Supreme Court would permit restrictions on abortion access, pro-choicers pushed for the passage of the Freedom of Choice Act (FOCA), which gave every woman the right to choose to terminate a pregnancy before viability and after viability if it is necessary to protect her life or health. FOCA would codify the Roe and Doe decisions and nullify existing state laws restricting abortion. The bill was introduced in 1989, 1993, and 2004, but languished in Congress. Pro-choice politicians, with the support of several pro-choice organizations, introduced FOCA again in Congress the day after the Gonzales decision. To date there has been no progress on the bill. Pro-choicers were successful at passing legislation that protects reproductive health clinics and its clients. Most notably, they passed the Freedom to Access Clinic Entrances Bill (FACE), a law that makes it a federal crime to use force, the threat of force, or physical obstruction to prevent individuals from obtaining or providing reproductive health care services. FACE was a response to rising clinic blockades and violence in the 1980s and 1990s.

The battle at abortion clinics

In the 1980s, pro-life activists, who felt that President Reagan had done little more than give lip-service to movement goals, decided to stop abortion by counseling women regarding other options, disrupting clinic operations, and using violence to close clinics. These activists share a moral abhorrence to abortion and regard the clinic as a location where they can effectively end the practice. Direct action groups differ in terms of whether they believe violence against clinic facilities and personnel is a justified and effective tactic. Those opposed to violence argue that sidewalk counseling outside of clinics is the best way to provide women the support and information necessary to prevent abortion. Those that use violence regard it as a legitimate way to defend the life of the unborn.

The pro-choice movement responded to efforts to close clinics in four ways. First, pro-choicers engaged in clinic defense and mobilized volunteers to escort women into abortion clinics. Second, pro-choice advocates passed state-level “buffer zones,” which required protestors to stay a specified distance away from clinic entrances and walkways. Third, pro-choice leaders publicly called on the president and Department of Justice to take steps to curb clinic violence. Pro-choicers contended that the incidents of clinic violence were part of a larger campaign designed to reduce women’s access to the abortion procedure. This line of argument fell on deaf ears until Clinton took office and asked Attorney General Janet Reno to investigate the incidents. Finally, as I discuss in Chapter 5, the National Organization for Women (NOW) along with two clinics sued pro-life activists under federal antitrust laws and charged the defendants with a “nationwide criminal conspiracy to close women’s health clinics.”

In short, the battle over abortion is a long and contentious one that is not reserved to political institutions alone. Likewise, while their composition varies, the pro-life and pro-choice movements consist of vibrant organizations that adopt a range of orientations, practices, and goals as they relate to the abortion issue. Both of these realities make the abortion case an excellent one for examining how activist groups use mass media to forward their goals over time and in response to larger movement and institutional dynamics.

Overview of the study and organizations

I analyze four organizations over a twenty-year period: the Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA), the National Organization for Women (NOW), the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC), and Concerned Women for America (CWA). PPFA and NOW are pro-choice organizations that support legal abortion, while NRLC and CWA are pro-life organizations that advocate for limited abortion availability. Because each of the groups is discussed in detail in the subsequent chapters, I give only an overview of them here.

Table 3.1 summarizes the basic characteristics of each organization. There are several general differences and similarities among the organizations worth mentioning. The organizations differ in their orientation to the abortion issue and goals. Both PPFA and NRLC are single-issue organizations, meaning they represent a limited set of grievances and work to achieve policy change on a fairly narrow set of issues. PPFA mobilizes around reproductive issues more broadly and NRLC focuses on protecting life “from womb to tomb.” NOW and CWA, in contrast, are multiple-issue organizations that seek policy change on a broad range of women’s public policy issues. As a conservative, Judeo-Christian women’s organization, CWA mobilizes around issues of reproduction, welfare, education, national security, and religious expression. NOW, which is a liberal feminist group, mobilizes around reproductive, economic justice, lesbian rights, and sexual discrimination. It also is clear from Table 3.1 that the organizations vary in size and general structure. While all of the groups have a formalized organizational structure and rely on a membership to fund organizational activities and campaigns, PPFA’s structure is more elaborate than those of the other groups; it has multiple national offices and affiliates, which offer reproductive health services in addition to engaging in activism, instead of chapters.

Table 3.1. Overview of the organizations, 1980–2001*

* Note: The membership and budget information presented above represent the average totals for the years in which data could be obtained between 1980 and 2001. NRLC only reported its membership from 1980 to1990 and it never reported its budget information. It did report chapter and state information for all the years. I combined the numbers to derive the average. PPFA did not report its membership and only reported its budget from 1987 to 2001. I used the information provided in the Encyclopedia of Associations and figures from the PPFA archives for 1980, 1981, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1987, and 1988 to derive the average. NOW reported membership and chapter information for all years between 1980 and 2001. It did report chapter, state, and region information separately, which I have combined to derive the average. The budget figures represent the following years: 1980, 1983, 1984, 1985, 1986, 1988, 1989, 1990, 1991, and 1992. CWA did not begin reporting information until 1983. Additionally, it reported budget information only for the years 1988 to 1998 and chapter information for 1984 to 1998. The averages, then, reflect only the years that information was reported.

These groups were included in the study for three reasons. First, they have different organizational identities and, therefore, appeal to different constituencies within their respective social movements. PPFA and NRLC have more elaborated identities than NOW and CWA insofar as they explicitly try to appeal to a broad segment of the population. NOW and CWA, in contrast, organize around more particularistic points of view (feminism and Christianity, respectively) and, consequently, appeal to narrower segments of the population. As discussed in Chapter 1, these variations should have implications for each organization’s reputation in the media field and influence how each uses media to forward its goals. Second, the groups are fairly comparable (CWA and NOW, and NRLC and PPFA), which permits an analysis of how movement composition affects the reputation and media strategy of an organization. Groups mobilizing around legal abortion may find it more difficult to maintain their reputation in the media field than a similarly situated pro-life group because there are more reputable competitors with whom they must compete for the media spotlight. Finally, the groups identified one another as a clear threat to their goals, which allows an analysis of how opposition affects media strategy.

The organizational analysis is based on several data sources. I read all of the newsletters for each of the organizations from 1980 to 2000 (approximately 2,000 pages for each group). Newsletters are an important data source because they document the strategies and campaigns of a group as well as clearly identify opponents and allies during a given historical moment. Likewise, newsletters provide accounts of group actions as they occur and, therefore, are useful for tracking how strategies and perceptions of mass media change over time. I also conducted archival research, which provided another way to assess how the groups, their strategies, and perceptions of mass media change over time. Archival records are particularly useful for uncovering strategies that are intentionally designed to not undergo public scrutiny and provide important insight into how structure as well as resource availability and allocation affect strategy.3

Additionally, I conducted interviews with current and past activists working with the organizations; many were interviewed on multiple occasions. The number of interviews varied and ran from thirty minutes to three hours. I conducted a total of twenty interviews: six with activists from CWA, ten with activists from NRLC, two with activists from PPFA, and two with activists from NOW. I also conducted fifteen interviews with journalists from a range of news media outlets including The New York Times, Time magazine, The Nation, Human Events, National Review, Ms. magazine, and media professionals working for ABC, CBS, and NBC news, in order to assess each group’s reputation on the abortion issue. Finally, I read historical accounts on each organization as well as all of the available newspaper, radio, magazine, and television media coverage mentioning each group from 1980 to 2000. The analysis is therefore based on tens of thousands of documents and a number of interviews by activists and media professionals.

Overview of media attention on the abortion issue

While scholars should be careful to disaggregate media coverage from media strategy, examining what kinds of actors get coverage can provide a baseline assessment of an organization’s reputation in the mass media field. Because organizations with a strong reputation will have more media opportunities and get more and higher quality media coverage over time, it is visible (to some extent) in coverage. Figure 3.1 shows the results of a content analysis of 1,424 media stories on the abortion issue in which all the actors mentioned in the news story were coded.4 Here, we see that activist voices often are included in abortion coverage. While this does not indicate the quality of coverage, pro-life and pro-choice organizations are included in more stories than any other category of actor. It is worth noting that pro-choice and pro-life groups are included in coverage at nearly identical rates. Again, while this does not provide insight into how various groups are covered, it is clear that journalists are presenting arguments that represent both sides of the abortion debate (also see Rohlinger Reference Rohlinger2002, Reference Rohlinger2007).

Figure 3.1. Overview of the kinds of actors mentioned in media coverage

Note: The categories of actors mentioned include religious actors, individuals representing companies that make drugs (e.g., the pill), the Alan Guttmacher Institute, White House representatives, leaders from other social movements, think tank spokespeople, radical pro-life organizations (such as Army of God), executive nominees, media professionals (e.g., other journalists), presidential and vice presidential candidates, medical professionals, non-medical academics (e.g., lawyers), other actors (e.g., unaffiliated individuals), bureaucrats, the current President or Vice President, pro-life activists, and pro-choice activists.

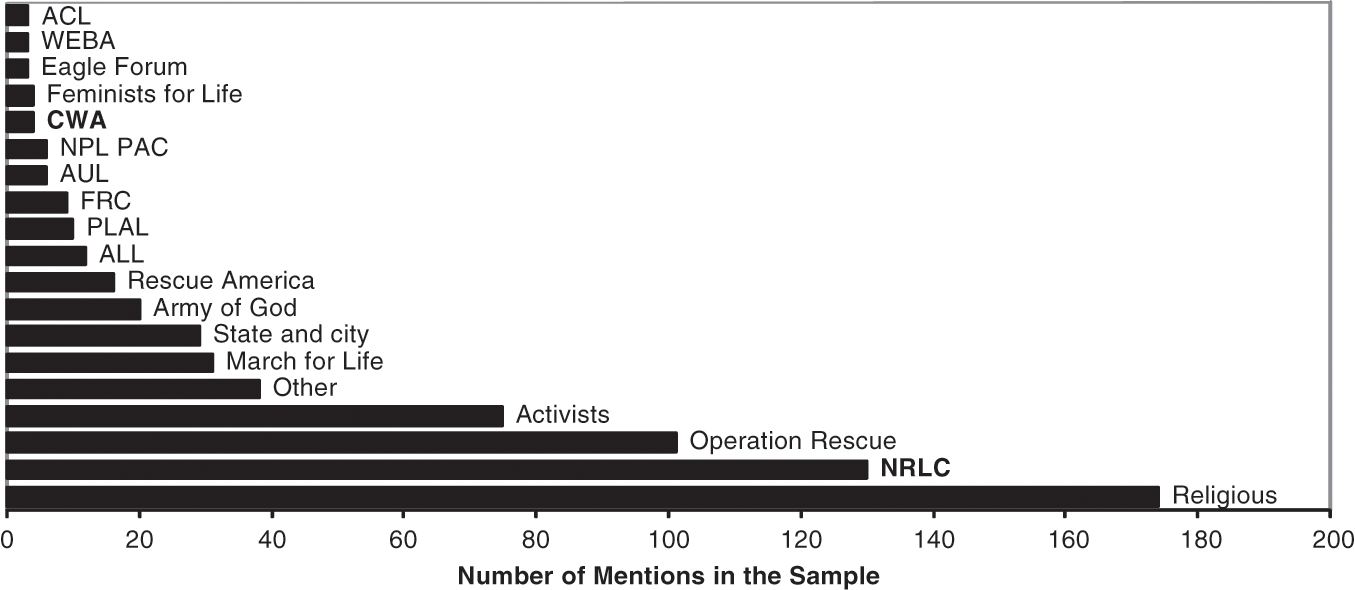

Figure 3.2 notes all of the pro-life organizations that were mentioned or quoted in coverage and highlights how much media attention NRLC and CWA received relative to other actors. The figure makes clear the diversity of the pro-life movement. In addition to national level organizations, the movement consists of state- and city-level pro-life groups, direct action organizations, and a vast contingent of denominationally diverse religious figures who routinely speak out against abortion. NRLC appears to have a strong reputation in the media field. NRLC, which is the organization with the most coverage, gets 130 mentions. Operation Rescue is second with 101 mentions and the March for Life a distant third with only thirty-one mentions. Only religious actors, a composite category that consists of all religious figures who spoke out against legal abortion in the sample, get more coverage. CWA gets very little media attention on the abortion issue. This does not seem to be a function of intramovement competition to represent women’s perspectives on abortion to the broader public. None of the other pro-life women’s groups, including Eagle Forum, Feminists for Life, or Women Exploited by Abortion, get much attention either. Instead, this seems to be a function of movement-level competition, suggesting that CWA does not have a strong reputation relative to other pro-life actors.

Figure 3.2. Overview of the pro-life actors mentioned in media coverage

Note: The “other” category consists of organizations that received two or fewer mentions in the sample. The “state and city” groups category consists of all state, county, and city level organizations in the sample. The most mentions one of these organizations received was three. The acronyms listed above stand for the following organizations: American Coalition of Life (ACL), Women Exploited by Abortion (WEBA), Concerned Women for America (CWA), National Pro-Life PAC (NPL PAC), Americans United for Life (AUL), Family Research Council (FRC), Pro-Life Action League (PLAL), American Life League (ALL), and National Right to Life Committee (NRLC).

There are fewer pro-choice actors mentioned within the context of abortion coverage, and nearly all of the actors are professional organizations (Figure 3.3). Compared to the pro-life movement, there are very few state- and city-level groups or unaffiliated actors included in the stories. Interestingly, the distribution of mentions in media coverage is skewed in favor of three groups: PPFA was mentioned in 191 stories, National Abortion Rights Action League in 149 stories, and NOW in one hundred stories. On its face, then, PPFA and NOW both appear to have relatively strong reputations in the mass media field, with PPFA leading the pack. In short, the compositions of the pro-life and pro-choice movements are quite different and this likely influences how individual groups use mass media to forward their goals.

Figure 3.3. Overview of the pro-choice actors mentioned in media coverage

Note: The “other” category consists of organizations that received two or fewer mentions in the sample. The “state and city” groups category consists of all state, county, and city level organizations in the sample. The most mentions one of these organizations received was three. The acronyms listed above stand for the following organizations: Abortion Rights Mobilization (ARM), Coalition of Abortion Providers (CAP), International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF), Family Planning Association (FPA), Center for Reproductive Law and Policy (CRL&P), National Abortion Federation (NAF), American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), National Organization for Women (NOW), National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), and Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA).

Figures 3.4 and 3.5 provide additional context for understanding each organization’s reputation on the abortion issue. Figure 3.4 shows the total number of mentions for each organization (regardless of the issue) in English newspapers for every year between 1980 and 2000, while Figure 3.5 plots the number of mentions each group received during the abortion events sampled during the same period.5Figures 3.4 and 3.5 show that PPFA’s media coverage climbed steadily over the twenty-year period and that it remained a prominent player in abortion coverage. This is true of NRLC as well, which also increased the amount of media attention it received over time. NOW and CWA, however, have a different pattern. While both organizations experienced an uptick in coverage in the late 1980s and early 1990s, by the late 1990s both groups encountered declines in coverage. NOW garners less attention on the abortion issue over time and CWA gets next to no coverage. This trend suggests that NOW experienced a decline in its reputation over time and that CWA’s uptick in coverage was not on the abortion issue. Reputation, in other words, may vary by issue. Although CWA did not get much coverage on the abortion issue, clearly it became a player on another cause. The remainder of the book examines media strategy in more detail and analyzes how NRLC, PPFA, NOW, and CWA respond to different media dilemmas over time. In doing so, I illuminate the factors that can lead to reputational decline and examine how actors can establish a reputation in new issue areas.

Figure 3.4. Number of mentions in American newspapers, 1980–2000

Figure 3.5. Number of mentions and quotes on the abortion issue, 1980–2000

1 As of February 2014, thirty-nine states require parental involvement in a minor’s abortion decision.

2 As of February 2014, twenty-six states require a waiting period before a woman can obtain an abortion, seventeen states mandate counseling, and 43 states allow institutions to refuse to provide the procedure to women.

3 PPFA documents are available through the Sophia Smith Collection at Smith College and at the Katherine Dexter McCormick library in New York City. NOW documents are available at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard University. Neither CWA or NRLC have formal archives. I was granted access to NRLC’s documents stored at the Greater Cincinnati Right to Life office and CWA’s documents at their Washington, D.C. office.

4 I sampled media coverage during thirty-six critical discourse moments in the abortion debate. I chose critical discourse moments that were (1) identified as important by scholars and activists and (2) represented wins and losses for both sides over time. Using Lexis-Nexis, indexes, abstracts, and manual inspection, I coded all media stories discussing the abortion issue during specified time frames. For anticipated events (such as legislative votes, presidential elections, executive nominations, and the Roe v. Wade anniversary), I coded media stories about abortion occurring before and after the event. For unanticipated events (such as clinic violence and the murder of Dr. Gunn), I coded media stories about abortion the date of and after the event. A detailed account of the sampling time frames for each critical discourse moment for each of the outlets is available in the methodological appendix on my website.

5 These data were obtained using LexisNexis, which includes 2,500 newspapers worldwide.