Women's judicial representation in Haiti has increased, from 2% of judges in the 1990s to 12% in 2020. This study explores why. A growing literature examines the link between conflict, political openings, and women's representation in decision-making (Tripp Reference Tripp2015). While most of this literature focuses on women's access to legislatures, little research thoroughly explores the link between postconflict settings and women's judicial representation. The dynamics of access to legislatures and courts are different, not least because deputies are elected, while judges are most often selected. A relatively small but growing subfield addresses women's access to judiciaries but focuses mainly on quantitative studies of women's access to high courts or on so-called stable and institutionalized democracies in the Global North. This qualitative study of the Haitian judiciary addresses this knowledge gap and allows for a more in-depth discussion of the mechanisms affecting women's judicial representation in a fragile context and the gendered consequences of state building.

In Haiti, years of authoritarianism and conflict have contributed to weak state institutions, poverty, and corruption. In 2020, Haiti ranked as the 13th most fragile country in the world (Fund for Peace 2020).Footnote 1 Since the fall of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986, Haiti has been stuck in a protracted and violent transition toward democracy (Faubert Reference Faubert2006), marked by political instability, coups, foreign intervention, natural disasters, and an inability to provide basic services to its citizens. Haiti has also undergone periods of extreme violence, most notably under the military-backed Raoul Cédras regime (1991–94), when 3,000 to 5,000 Haitians were killed (Mobekk Reference Mobekk2016).Footnote 2 Several scholars thus situate Haiti within the postconflict literature, despite its not coming out of a civil war (see Buss and Gardner Reference Buss, Gardner, Picard, Groelsema and Buss2015; Donais Reference Donais2012; James Reference James2010; Kolbe Reference Kolbe2020; Muggah Reference Muggah2005; Quinn Reference Quinn2009; Seraphin Reference Seraphin2018). International actors have been heavily involved in state- and peace-building efforts, particularly through several United Nations (UN) peacekeeping missions, which have included millions of dollars in justice support to strengthen the judiciary and rid it of its authoritarian heritage (Cavise Reference Cavise2012; Mobekk Reference Mobekk2016).

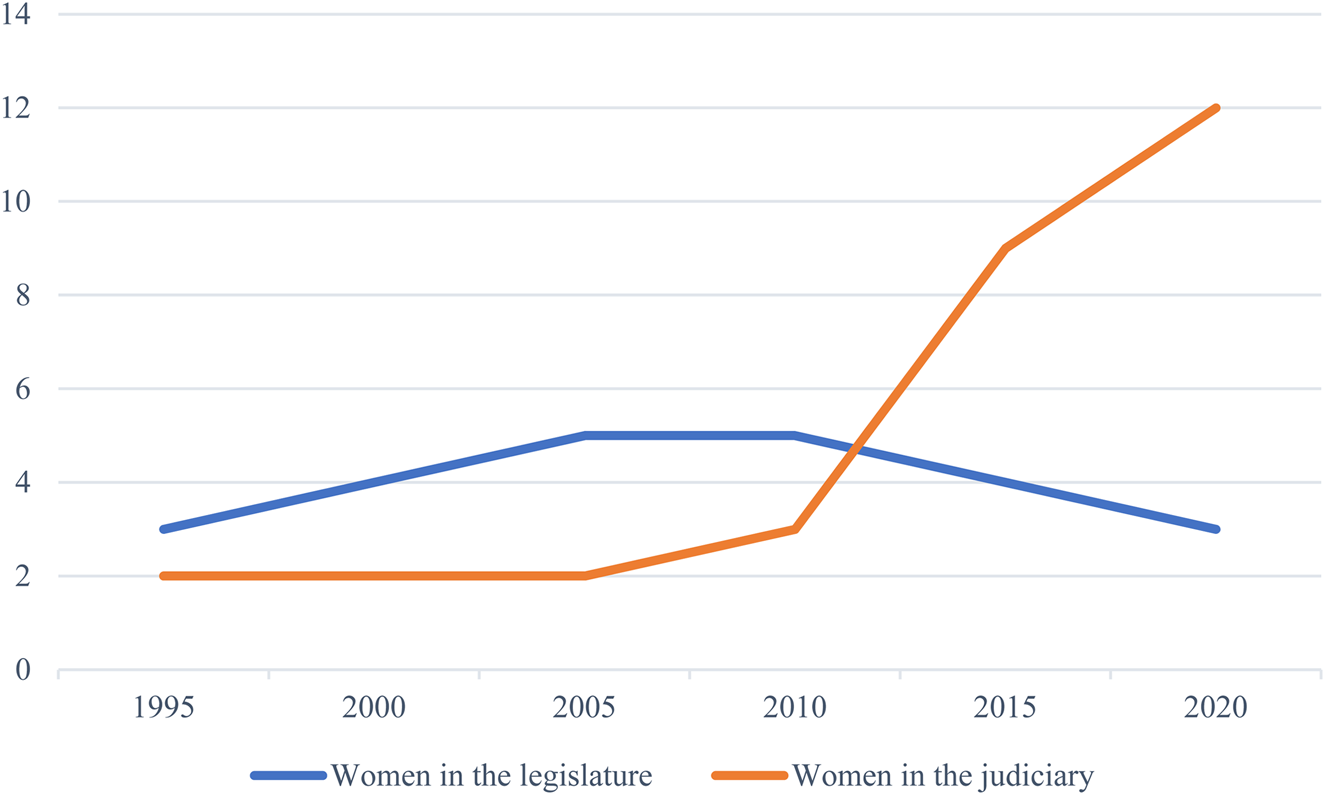

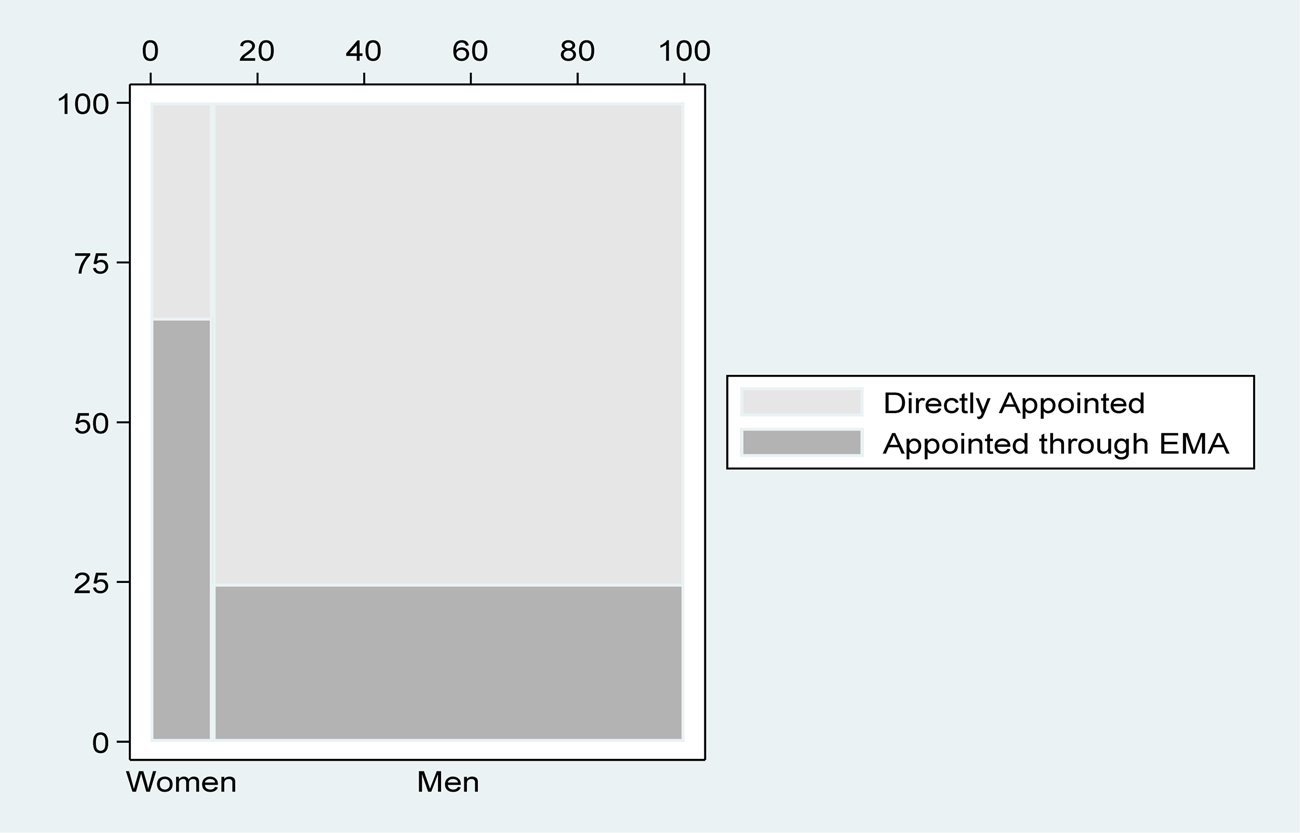

Haiti scores extremely low in terms of women's representation in decision-making bodies and lags far behind its Latin American and Caribbean neighbors. In the Haitian parliament, women make up just 3% of the lower chamber and 4% of the Senate (IPU 2020). When it comes to women's presence in the judiciary, however, recent decades have seen growth, from 2% in the 1990s to 12% in 2020 (see Figure 1).Footnote 3 This is a moderate achievement compared with the rest of Latin America, where the average proportion of women judges is 31% (ECLAC 2020). Still, Haiti is interesting because it diverges from many other conflict-affected societies where more women have accessed both the legislative and judicial arenas (see Tripp Reference Tripp2015; and Appendix A in the supplementary material online). The numbers suggest that something has taken place in Haiti's judicial sector that is not (yet) mirrored in the legislative sphere. In this article, I explore this puzzle by pursuing the following research question: what can explain the increase in the number of women judges in postconflict Haiti?

Beyond the intrinsic value of having more women in key decision-making roles, gender diversity on the bench is important as it may improve legitimacy and public confidence in the judiciary (Clayton, O'Brien, and Piscopo Reference Clayton2019; Grossman Reference Grossman2012; Malleson Reference Malleson2003; Rackley Reference Rackley2013). This is especially important in fragile state settings like Haiti, where government institutions are weak and people's trust in the judiciary is low. Although the literature on the effects of a judge's gender on decision-making is largely inconclusive,Footnote 4 a more gender-diverse judiciary may motivate female victims of violence during and after conflict—who often face trivialization and discrimination by justice actors (Jagannath Reference Jagannath2011)—to bring their cases to court.

To explain the increase in the number of women judges in Haiti, I collected descriptive statistics and interviewed 69 key informants, including 50 Haitian magistrates (judges and public prosecutors) of both genders and at all court levels. Research was conducted during five months of fieldwork in Haiti between late 2018 and early 2020. I find that the increased number of women in the judiciary in Haiti is less an effect of explicitly women-friendly policies than a by-product of general judicial reforms, supported by international donors to create a more independent, professional, and well-functioning judiciary. Although important legislation to promote more women to decision-making bodies, including the judiciary, has been adopted in Haiti, real implementation is still lacking. I argue that the introduction of more transparent and merit-based procedures for appointment to the judiciary through competitive examinations has helped women circumvent the predominantly male power networks that previously excluded them. This shows how state building in itself can contribute to gender equality without necessarily having an explicit gender agenda.

WOMEN IN THE HAITIAN JUSTICE SYSTEM

Haiti was born out of a successful slave revolt against its French colonizers and adopted France's civil law judicial system after independence in 1804 (Romero Reference Romero2012). This entails a system of magistrates: sitting magistrates (magistrats du siege) are the judges, while standing magistrates (magistrats du parquet or commissaires du gouvernement) are the public prosecutors. Education and appointment procedures are the same for judges and public prosecutors, and it is not uncommon to work as both during a career. The public prosecutor defends the interests of society and public order and has no fixed mandate, whereas the judges’ mandates lasts from 3 to 10 years, depending on court level (Comparative Constitutions Project 2013). Haiti has one Supreme Court (Cour de Cassation), five appeals courts (cours d'appel), 18 courts of first instance (tribunaux de première instance), and 179 peace tribunals (tribunaux du paix) spread across the country. There are also special courts for cases concerning land, minors, and labor (CSPJ 2018a).

Magistrates in Haiti are appointed either directly (integration directe) or, since 1996, through the magistrate school (Ecole de la Magistrature, or EMA). According to law, directly appointed magistrates start their careers in the lower rungs of the court in peace tribunals or courts of first instance, which is also the norm for magistrates appointed through the EMA.Footnote 5 The law also states that promotions and renewals of judges’ mandates must go through the High Judicial Council (Conseil Supérieur du Pouvoir Judiciaire, or CSPJ) before being approved by the president (Le Moniteur 2007). The first woman magistrate, Ertha Pascal-Trouillot, entered the court of first instance in Port-au-Prince in 1975. In the mid-1990s, the number of women judges was a meager 2%.Footnote 6 By 2013, the proportion had increased slightly to 5%. By 2020, the proportion had more than doubled to 12% (CSPJ 2015, 2018b; United Nations 2014). The total number of judges has varied over time because of a complex system of appointments and vetting but increased from 660 in 2013 to 867 in 2020 (CSPJ 2020). Data for public prosecutors could not be obtained for this study.

The focus of this study is women's entry to rather than mobility within the judiciary. It is still worth mentioning that Haiti differs from the global norm in that fewer women are found in the lower courts (10% in peace tribunals). This is likely because most peace tribunals are found in rural areas, whereas women judges—in Haiti and elsewhere—are often found in and around cities (Cook Reference Cook and Flammang1984b; Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim, Bauer and Dawuni2016). A general lack of security measures in peace tribunals and more informal recruitment procedures for justices of the peace may contribute to this trend (Tøraasen, Reference Tøraasenforthcoming). The recent drop in the number of women in peace tribunals and courts of first instance may be due to a temporary stop in the influx of women from below, as the last class from the magistrate school graduated in 2016 (see Table 2).Footnote 7

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND: WOMEN'S ACCESS TO JUDICIARIES

Women are entering decision-making roles in increasing numbers around the world, and the judiciary is no exception. Women make up approximately 27% of the world's judges, although the numbers vary greatly among countries and courts (O'Neil and Domingo Reference O'Neil and Domingo2015).Footnote 8 Knowledge of women's access to the judiciary is largely based on the Global North (see, e.g., Boigeol Reference Boigeol1993; Kenney Reference Kenney2013a; Rackley Reference Rackley2013), especially U.S. courts (Cook Reference Cook1982, Reference Cook and Flammang1984b; Goelzhauser Reference Goelzhauser2011; Resnik Reference Resnik1991). Researchers also tend to focus on more prestigious courts, be it women's entry to international courts (Dawuni Reference Dawuni2019; Dawuni and Kuenyehia Reference Dawuni and Kuenyehia2018; Grossman Reference Grossman2016) or comparative studies explaining global and regional variations in the number of women in countries’ highest courts (Arana Araya, Hughes, and Pérez-Liñán Reference Arana Aráya, Hughes and Pérez-Liñán2021; Arrington et al. Reference Arrington, Bass, Glynn, Staton, Delgado and Lindberg2021; Dawuni and Kang Reference Dawuni and Kang2015; Dawuni and Masengu Reference Dawuni, Masengu, Sterett and Walker2019; Escobar-Lemmon et al. Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Hoekstra, Kang and Kittilson2021; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Kittilson, Hoekstra and Escobar-Lemmon2020; Thames and Williams Reference Thames, and Margaret and Williams2013; Valdini and Shortell Reference Valdini and Shortell2016). Fewer studies include lower courts when explaining women's access to judiciaries beyond the Global North, with some notable exceptions (Bauer and Dawuni Reference Bauer and Dawuni2016; Bonthuys Reference Bonthuys2015; Kamau Reference Kamau, Schultz and Shaw2013; Kenney Reference Kenney, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2018; Sonnevold and Lindbekk Reference Sonnevold and Lindbekk2017). This is understandable given the scarcity of global statistics on women's presence in lower court levels. Our understanding of the mechanisms that influence entry to the judiciary thus remains limited, amplified by the shortage of qualitative in-depth case studies from diverse contexts.

Scholars explain women's access to courts with different structural and institutional factors that often work in tandem. Improved educational possibilities in law for women increase the pool of eligible women judges (Sonnevold Reference Sonnevold, Sonnevold and Lindbekk2017; Williams and Thames Reference Williams and Thames2008), as do changes in cultural gender norms toward leadership and family life (Duarte et al. Reference Duarte, Oliveira, Gomes and Fernando2014; Dawuni Reference Dawuni, Bauer and Dawuni2016; Ibrahim Reference Ibrahim, Bauer and Dawuni2016). However, the number of women judges rarely reflects the number of women law graduates or practicing lawyers, leading several scholars to debunk the trickle-up argument (Cook Reference Cook1984a; Grossman Reference Grossman2016; Kenney Reference Kenney2013a; Rackley Reference Rackley2013). Research from Africa (Bauer and Dawuni Reference Bauer and Dawuni2016) and the Muslim world (Sonnevold and Lindbekk Reference Sonnevold and Lindbekk2017) suggests that access to legal education for women is a necessary but not sufficient condition for women's increased judicial representation.

Researchers also highlight the importance of judicial appointment procedures. Where appointments are based on rational and transparent criteria—such as competitive examinations—women tend to do better. Where appointments are based on career achievements, professional visibility, and “cronyism”—that is, being known to the appointer—women are disadvantaged (Schultz and Shaw Reference Schultz, Shaw, Schultz and Shaw2013). The latter approach often requires access to influential and mostly male-dominated networks (Kenney Reference Kenney2013a; Schultz and Shaw Reference Schultz, Shaw, Schultz and Shaw2013). Similar patterns can be seen in women's access to other decision-making roles (Kittilson Reference Kittilson2006; Rothstein Reference Rothstein, Stensöta and Wängnerud2018). We know from the literature on women in politics that informality and shadowy practices in recruitment are known to benefit those already privileged—who in most systems tend to be men—while effectively excluding women (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2013). The difference in appointment procedures is part of the reason why we tend to find more women in civil law countries like France (64% women judges), where entry to the judiciary is determined by examination results (Boigeol Reference Boigeol, Schultz and Shaw2013), compared with common law countries like the United Kingdom (32% women judges), where recruitment is characterized by secret soundings and the “tap on the shoulder” technique (Rackley Reference Rackley2013). Different perceptions of judges’ roles (political versus bureaucratic) in legal cultures and the accompanying prestige is another reason why there tend to be more women in civil law countries than in common law countries (Remiche Reference Remiche2015; Schultz and Shaw Reference Schultz, Shaw, Schultz and Shaw2013).

We usually find more women judges where there are policies and practices in place to ensure a representative balance (Rackley Reference Rackley2013, 20). Gender quotas are on the rise, but they are still rarely used in judiciaries (Kamau Reference Kamau, Schultz and Shaw2013; Malleson Reference Malleson2009, Reference Malleson2014; Piscopo Reference Piscopo2015). A more common approach is to rationalize the appointment criteria used by judicial appointment commissions and other gatekeepers as being more transparent and merit based (Cook Reference Cook1982; Dawuni and Kang Reference Dawuni and Kang2015; Kenney Reference Kenney, Schultz and Shaw2013b; Morton Reference Morton, Malleson and Russell2006). Still, even so-called merit-based selection processes may do little for women's inclusion on the bench without a commitment to increasing women's numbers (Crandall Reference Crandall2014; Russell and Ziegel Reference Russell and Ziegel1991; Torres-Spelliscy, Chase, and Greenman Reference Torres-Spelliscy, Chase and Greenman2010), as the meaning of merit was constructed “around the needs of certain preferred groups in a way which has unfairly advantaged them” (Malleson Reference Malleson2006, 136). Since the typical judge for a very long time was male, merit is not necessarily a gender-neutral concept. For the sake of clarity, when I refer to merit-based appointment procedures in the context of Haiti, these are competitive examinations through the magistrate school.Footnote 9

Contextual factors, such as a strong women's movement and political will among decision makers, matter for the implementation of these measures (Hoekstra, Kittilson, and Bond Reference Hoekstra, Kittilson, Bond, Escobar-Lemmon and Taylor-Robinson2014; Htun and Weldon Reference Htun and Weldon2018; O'Neil and Domingo Reference O'Neil and Domingo2015; Schultz and Shaw Reference Schultz, Shaw, Schultz and Shaw2013). Some studies find that as the number of women in legislatures increases, the number of women judges on higher courts also increases (Thames and Williams Reference Thames, and Margaret and Williams2013). Dawuni and Kang (Reference Dawuni and Kang2015) find that transnational sharing may explain why some African countries appoint women to leadership positions in the judiciary. Pressure from the international community may also influence decision makers to adopt gender-friendly policies that target women's underrepresentation in decision-making (Bush Reference Bush2011; Hughes, Krook, and Paxton Reference Hughes, Krook and Paxton2015).

Institutional and social ruptures may also give rise to women in decision-making roles. With democratic openings and the demise of violent conflict, women's movements often use the opportunity to claim their rightful place in the new society and create women-friendly laws and institutions, such as gender quotas. Such efforts have been supported by international actors that have put women's representation high on the agenda over the past several decades (Tripp Reference Tripp2015). While most empirical research explores the link between postconflict settings and women's access to legislatures (Burnet Reference Burnet, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012; Hughes and Tripp Reference Hughes and Tripp2015; Muriaas and Wang Reference Muriaas and Wang2012; Tønnessen and al-Nagar Reference Tønnessen and Samia2013; Tripp Reference Tripp2015); Dawuni and Kang (Reference Dawuni and Kang2015) find that the end of violent conflict, combined with a strong women's movement, may factor in the rise of women to leadership positions in African high courts. Democratic transitions in Africa have opened opportunities for women to become judges at different court levels as a result of the adoption of new, progressive constitutions and laws pertaining to women's rights (Bauer and Dawuni Reference Bauer and Dawuni2016; Kamau Reference Kamau, Schultz and Shaw2013). Emerging research finds that institutional ruptures—often linked to postconflict and fragile settings—help women advance to higher courts when changes are made to constitutional rules for appointment (Arrington et al. Reference Arrington, Bass, Glynn, Staton, Delgado and Lindberg2021) and when there is political will (Arana Araya, Hughes, and Pérez-Liñán Reference Arana Aráya, Hughes and Pérez-Liñán2021). Still, we know little about how conflict, institutional ruptures, and political openings may influence women's entry to the judiciary as a whole.

Another unexplored relationship is that between donor-supported judicial reform and women's judicial representation. The frailty of the judicial system in many postconflict and fragile states has made donor-supported judicial reform a key priority in state-building efforts (Lake Reference Lake2018). A crucial goal of judicial reform is to create more robust and independent judiciaries in order to establish the rule of law (Sutil Reference Sutil, Méndez, O'Donnell and Pinheiro1999, 260). One way to achieve this may be to professionalize the judiciary by strengthening merit-based appointment procedures, making judicial appointments less politicized and, by extension, judiciaries more independent. Based on what we know about the importance of merit-based appointments for women's judicial representation (Kenney Reference Kenney2013a; Schultz and Shaw Reference Schultz, Shaw, Schultz and Shaw2013), such reforms may also improve women's access to the judiciary. Thus, there is a theoretical but largely unexplored link between state building, judicial reform, and women's judicial representation in fragile and conflict-affected contexts.

Based on these strands of literature, we can draw two hypotheses about the causes of the increase of women in the Haitian judiciary since the 1990s. With the demise of conflict and democratic openings, we can expect that (1) the introduction of women-friendly policies such as gender quotas led to an increase of women in the judiciary, or that (2) state-building efforts aimed at strengthening the judiciary transformed appointment processes to be more favorable to women, thus increasing women's judicial representation.

METHODOLOGICAL APPROACH

In addition to primary and secondary sources and descriptive statistics, this study relies on 69 in-depth and semistructured interviews conducted during five months of fieldwork in Haiti between late 2018 and early 2020. I talked to a heterogeneous sample of 50 Haitian magistrates of both genders—32 women and 18 men—from both rural and urban jurisdictions in Haiti and at all court levels. My interviewees also vary with regard to age, family background, and how they were appointed as magistrates. Some entered the magistracy in the 1970s, while others had recently started their career. Some were from families of judges and lawyers, while others had parents who were teachers or merchants, or were even illiterate. A little over half of the interviewed were appointed through the magistrate school (EMA), and the rest through direct appointments. I also spoke to retired magistrates. To find the causes for the increase in women's judicial representation, I asked magistrates about their professional background, how they became magistrates, and any challenges connected to appointments and their general working life.

At the time of the research, Haiti was going through one of its worst sociopolitical crises of recent decades. This made data collection particularly challenging, with roadblocks and political unrest preventing travel to large parts of the country. Consequently, most of my interviewees were based in and around the capital, Port-au-Prince. To get in touch with interviewees, I started by contacting a female judge at the Port-au-Prince appeals court and member of the Chapitre Haïtien de l'Association Internationale de Femmes Juges, a chapter of the International Association of Women Judges,Footnote 10 who introduced me to several other magistrates. Eventually, I also received a list of all of Haiti's judges with contact information from the CSPJ. This helped me obtain a certain degree of representativeness in the selection of interviewees, as I could reach out directly to magistrates instead of relying entirely on the snowball method.

For contextual insight, I interviewed 19 other representatives from women's groups, civil society, the United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (MINUJUSTH), other international organizations, and the CSPJ, as well as journalists and academics. Although most of my interviewees agreed to having their names published, the security situation for justice actors in Haiti has taken a turn for the worse since data collection. To protect my interviewees, I have thus chosen to anonymize everyone. Most interviews were held in French, and I have translated quotations into English.

As few statistics were available online, the CSPJ provided relevant information for this study. Haiti only officially started keeping count of its judges after the creation of the CSPJ in 2012. Thus, complete historical information about the evolution of women's judicial representation in Haiti could not be obtained for this study. Additionally, the Ministry of Justice could not provide complete statistics on prosecutors. However, as the number of prosecutors usually is much smaller than the number of judges (Schultz and Shaw Reference Schultz, Shaw, Schultz and Shaw2013, 7), I trust the statistics to be fairly accurate.

FINDINGS: WHAT EXPLAINS WOMEN'S INCREASED JUDICIAL REPRESENTATION IN HAITI?

Based on the literature, I hypothesized that the increase in women in the Haitian judiciary can be explained by gender reform adopted in the wake of conflict and democratic openings. I also hypothesized that state-building efforts aimed at strengthening the judiciary transformed appointment processes to be more favorable to women, thus increasing women's judicial representation. In this section, I examine these hypotheses.

Women-Friendly Policies: Adopted but Not Implemented

Indeed, several women-friendly laws were adopted in the past several decades after pressure from domestic women's groups and international donors. After being suppressed by the Duvalier dictatorship for decades, the Haitian women's movement proliferated and pushed for the formal recognition of equality between women and men in the 1987 constitution in order to create a “socially just Haitian nation” after the fall of dictatorship (Charles Reference Charles1995; Merlet Reference Merlet, Maier and Lebon2010). In 1990, Haiti's first female supreme court judge, Ertha Pascal-Trouillot, was named provisional president and organized Haiti's first free elections, which brought leftist Catholic priest Jean-Bertrand Aristide to power, only to be overthrown in a military coup that same year. When Aristide was reinstated in 1994 with the backing of U.S. troops and the UN, he established the Ministry of Women's Affairs to promote national equality policies (Haiti Equality Collective, 2010, 5). Years of continuing political instability, social unrest, and sporadic violence followed, leading to Aristide's second ouster in 2004 and the deployment of the UN Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) to restore democracy and stability and to reform Haiti's fragile institutions (Duramy Reference Duramy2014, 27).

In 2012, a small group of five women deputies, women's rights organizations, and international actors, including MINUSTAH, the UN Development Programme (UNDP), and International IDEA (MINUSTAH 2012; United Nations 2014), pushed for the adoption of a constitutional amendment on gender quotas. The quota amendment stipulated that “[t]he principle of a minimum 30 per cent quota for women shall apply to all levels of national life, and in particular to public services” (United Nations 2014, 19), which includes the judiciary. Other women-friendly advancements in the same period include a Gender Equality Policy (2014–34) and a National Plan for Action (2014–20), a Gender Equity Office in Parliament (2013), an Office to Combat Violence against Women and Girls (2013), and an Interministerial Human Rights Committee (2013), mandated to assist in gender mainstreaming all state agencies (Bardall Reference Bardall2018).

However, the implementation of these gender reforms is still lacking. The 2012 constitutional amendment contained no implementing legislation and no sanctions for noncompliance, rendering the gender quota practically useless. The disappointment in the quota became evident in the national election of 2015, when zero women ended up being elected to parliament (Bardall Reference Bardall2018). As stated by a women's rights activist,

There was never a law for application. So, we have not benefited from this, it is not effective. It exists in the constitution, but there is no law for application. There should follow something about how one is to actually [implement] it. One doesn't know how to do it, how to respect these 30%.Footnote 11

My interviewees confirmed that the gender quota is not respected in the judiciary either. As stated by a former prosecutor, “We have this 30% quota law. Is it applied? No.”Footnote 12 Several interviewees attributed the failing implementation of gender reform to a lack of political will and a lack of capacity among both international and national actors, on the governmental and civil society levels. According to a representative from the Ministry of Women's Affairs,

The Haitian state does not really have a gender policy. Also, ministers have neglected it . . . The Ministry of Women's Affairs does not have the means to do anything . . . There is no will to increase women's representation. They have to follow up. The actors are not motivated. Neither national nor international actors are focused enough . . . International actors talk a lot about violence against women, like “blah blah blah.” They do not have focus on women's participation in public roles.Footnote 13

Further, the catastrophic 2010 earthquake—in which three of the Haitian women's movement's most prominent leaders lost their lives—disrupted ongoing state programs and projects related to gender equality and diverted all energies to emergency assistance (United Nations 2014). The only area in which gender was addressed in the postdisaster needs assessment was in relation to gender-based violence, while leaving women “out of the equation when it comes to rebuilding the country's judicial, administrative, legislative and democratic systems” (Haiti Equality Collective 2010, 3; Tøraasen Reference Tøraasen2020). According to activists interviewed for this study, implementing the gender quotas of 2012 and the successive gender-friendly policies has been challenging in a country still recovering from disaster. Political instability and the lack of consistency in government has further made it difficult to find dedicated allies within the state that could push for real implementation of gender reform. Previous governments have shown little interest in achieving gender equality,Footnote 14 as exemplified by a cut in funding to the Ministry of Women's Affairs from 1% to 0.3% in the 2016 state budget (Bardall Reference Bardall2018). Research shows that gender-friendly constitutional demands for women's inclusion into decision-making spheres are far from self-executing (Kenney Reference Kenney, Alexander, Bolzendahl and Jalalzai2018). Hence, because of lack of implementation, gender-targeted reforms fall short of explaining the increase of women judges in Haiti.

Judicial Reforms as State Building: Gender Representation through Professionalization

Haitian civil society actors and international donors have initiated numerous judicial reform projects since the 1990s, with the aim to create a well-functioning and independent judiciary. Years of authoritarianism and violent conflict have left the Haitian judiciary largely dysfunctional, with widespread corruption and impunity, arbitrary arrests, prolonged detention, inhumane prison conditions, torture and summary executions, unending delays, lack of counsel, and incompetent judges (Cavise Reference Cavise2012). Since just 1% of the national budget is allocated to the justice system—and 11% of this is allocated to courts—international funding is crucial for judicial reforms (Berg Reference Berg2013). The main donors are the United States, followed by Canada, the European Union, France, the UNDP, and the Organization of American States. Since 2004, the MINUSTAH has had a clear mandate to support judicial reform, contributing both human and financial resources to strengthen the judiciary as an institution. Together with other international donors, the UN missions provided more than US$75 million in foreign support to the justice system between 1993 and 2010. This included, among other initiatives, training of magistrates, management practices of judicial institutions, reform of outdated legal codes, rehabilitation of courts, access to justice, technical assistance and advice to the Haitian Ministry of Justice, and purging of incompetent or corrupt judges (Mobekk Reference Mobekk2016).

Several studies have indicated the limited success of these judicial reforms, especially in terms of creating an independent and well-functioning judiciary (Berg Reference Berg2013; Cavise Reference Cavise2012; Democracy International 2015; Mobekk Reference Mobekk2016). However, these studies have not focused on the impact of these reforms on women's access to the judiciary. In this study, I find that judicial reforms have introduced an alternative route to the judiciary, which is more transparent and based on competitive examinations, through the creation of the magistrate school (EMA) in 1996. In the next section, I present the ways in which the tradition of direct appointments has worked against women's judicial inclusion and how the route through the EMA has helped women find a way in.

Direct Appointments and the Importance of (Male) Power Networks

The norm in Haiti is direct appointments to the judiciary (intégration directe). According to law, candidates for direct appointment must be law graduates with at least five years of relevant experience, who are nominated on lists by departmental and municipal assemblies, submitted to the president of the judiciary, followed by a shorter probatory internship organized by the EMA. The CSPJ is responsible for ensuring that magistrate candidates to peace tribunals, courts of first instance, and appeals courts fulfill all these conditions (Le Moniteur 2007).Footnote 15 But in reality, the process is much more arbitraryFootnote 16 and remains highly politicized. According to many of my interviewees, what really matters for appointments is who you know close to power. One female magistrate claimed that following the formal process for application was not enough. It was also crucial to make phone calls to “the right people,” or else your application would be “lying in a drawer somewhere.”Footnote 17 As stated by another woman magistrate,

The constitution stipulates the process, but it is not really respected. If a lawyer is in the system with a lot of experience, he can be nominated as prosecutor or judge. But with the interference of the two other powers, the executive and legislative, one can nominate whoever as a sitting or standing magistrate.Footnote 18

Several of the magistrates I talked to claimed that gatekeepers in the judiciary—who were almost always men—favored other men, even when qualifications and professional experience were equal. As stated by a woman justice of the peace, “Here, we always tend to prioritize men. I see that women have much more order and are also competent . . . But in the legal system, men are given priority over women.”Footnote 19 Several interviewees linked this to cultural norms and stereotypes about gender and leadership. And despite the past decade's increase in women, the magistracy was still largely defined as a “profession for men.” A woman judge in the appeal's court said the following about accessing judicial posts:

Oh, the challenges are huge! Normally, it is true that there are equal conditions, which say that to access these posts you must have so or so much [experience]. Generally, us women, even if we fill out all the conditions, it is very difficult. Very difficult for us to access these posts.Footnote 20

In particular, it was considered challenging for women to gain access to the judiciary through direct appointments. The directly appointed female magistrates in my sample confirmed the importance of political contacts: one had worked with the Ministry of Justice for years before becoming a prosecutor, another was nominated by a female local deputy, and a third said it would be challenging to become a judge if the person responsible for appointments was “not her friend.” As stated by a female former judge, “[V]ery few women generally join the judiciary [through direct appointment]. Unless it is a woman who is a good friend of a politician; you can see that this person joins the judiciary. No problem. But not many. It is rather men.”Footnote 21 Thus, the overall dynamic of direct appointments appears to be both informal and highly gendered. A young female prosecutor stated,

The executive power and the legislative power keep the judiciary in check. Men have a tendency of collaborating with their peers. I think this is the reason why so few women are high up in the magistracy . . . So, it is often said that [laughter] the men, to collaborate, to reach their goals—so you know there's a lot of corruption out there in Haiti—the men collaborate with each other. And it would be very difficult for women to let themselves be involved in this corruption. So, this is why I think, for me, that we have not [reached the quota level] in the judiciary. One often says that for men to reach their goals, they collaborate together.Footnote 22

A male judge had similar observations about appointments, gender, and powerful networks:

The problem with politics [in judicial appointments] is that it is not based on competences. So, it's about who you are, who you know, your network . . . It is men who dominate the networks in this country! And the place that we leave to women? Oh, to have a place as a woman in this society, it takes a lot of effort. It really takes a lot of effort.Footnote 23

Haiti is still transitioning from its authoritarian past, and democracy remains fragile.Footnote 24 In the absence of strong political parties and organizations, political elites have tried to ensure political power over the judicial system (Berg Reference Berg2013; Fatton Reference Fatton2000; Mobekk Reference Mobekk2016). Direct appointments thus offer a way for the Haitian government to maintain control over the judiciary. The absence of women from political institutions has influenced today's institutional culture, in which “the masculine ideal underpins institutional structures, practices and norms” (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell Reference Mackay, Kenny and Chappell2010, 582). This has created largely male networks of power, where women are disadvantaged as “outsiders” and rarely have access (Schultz and Shaw Reference Schultz, Shaw, Schultz and Shaw2013). In contexts like Haiti, women have less of what Bjarnegård (Reference Bjarnegård2013) refers to as homosocial capital, a form of gendered social capital that helps men profit from clientelist networks. As a result of gendered power structures and norms, the system of direct appointments has helped maintain informal discrimination against women, which might explain why in the 1990s a meager 2% of magistrates were women. It was not until judicial reform efforts in the 1990s and 2000s that appointment procedures became more merit based and transparent, notably through the magistrate school, which, I argue, was instrumental in opening up opportunities for women's access to the judiciary.

Merit-Based Appointments through the Magistrate School

The magistrate school (EMA) was envisaged in the 1987 constitution, but it was not opened until the end of the military regime and the return of President Aristide in 1996. The EMA was later forced to close down for six years because of political turmoil, but it reopened with the adoption of an important law package in 2007 that also regulated the function and career standards of magistrates and established the first independent organ overseeing the justice sector, the CSPJ. The purpose of the EMA is to train a “new breed” of more professional, competent, and independent judges and prosecutors (Berg Reference Berg2013). The EMA provides 16 months of initial training for law graduates to become magistrates, as well as additional training for already practicing magistrates.

International support—from the UNDP, European Union, UN missions, Canada, France, and the United States—has been vital for both establishing and maintaining the EMA (Mobekk Reference Mobekk2016). For instance, the teachers at the EMA still receive their salary from international donors.Footnote 25 During its 25 years of existence, the school has educated 256 magistrates in six classes. To enroll at the EMA, aspiring magistrates must take an entry exam. Appointments to the judiciary happen shortly after graduation, depending on available posts. The process is based on academic qualifications and examination results. The top students can choose where they will be deployed as magistrates after graduation.Footnote 26 Appointments through the EMA are thus based on competitive examinations, and academic achievements are rewarded rather than political contacts. Several of the women magistrates I talked to who had chosen to go through the EMA saw this as a better opportunity for people without the right acquaintances. As stated by one female justice of the peace,

I went through the magistrate school because I didn't have any political contacts. [For direct appointment] you must have contacts. It is made through contacts. You must have a thesis, then you must be lawyer, then you must have contacts. The hierarchy is made like that. Those who have no contacts like me, I still have the chance to participate through the magistrate school, so I had no need for that. That is reality. You must know people. Someone who can present you, who trust you. Those are usually nominated [directly]. So, if you are nominated directly, you owe someone something. They are doing you a favor. If you are appointed through the school, on the other hand . . . I don't know anyone.Footnote 27

A woman judge at the court of first instance noted that she had chosen the route through the EMA since direct appointments were “too political” for her: “You need to have what we call ‘a parent.’ That means someone to do the lobbying for you, et cetera. So, I like studying and it is much easier for me to access the magistracy [through the EMA].”Footnote 28 Similarly, a male judge noted that with the creation of EMA, the magistracy became more accessible to women:

There have always been some women [in the magistracy] from prominent families. But then there was [the] EMA. Outside of the school, one can be nominated by direct appointment. These appointments are most often marked by “amity.” But with the reopening of the school, the number [of women magistrates] increased a bit more . . . [W]ith [the] EMA, one encourages women to go through another route.Footnote 29

According to a woman judge, many women choose to go through the EMA because of the culture of law firms, where unwanted sexual advancements are part of daily life.Footnote 30 Direct appointments officially require several years of experience as a practicing lawyer. The EMA may thus provide a more attractive alternative for female lawyers set on becoming magistrates, without having to endure uncomfortable behavior from their male colleagues in law firms. Similar claims were made by another female judge who stated that women were sometimes met with demands for sexual favors in return for being appointed directly to the magistracy:

For a man it is easy, if he has a friend, and he is a man, it is easy for him, he will give him a job. For a woman, there must be a precondition . . . When a woman has finished her law degree, she can continue as a lawyer or integrate into the magistracy. Even if she is competent, people may say that “it takes a night” still.Footnote 31

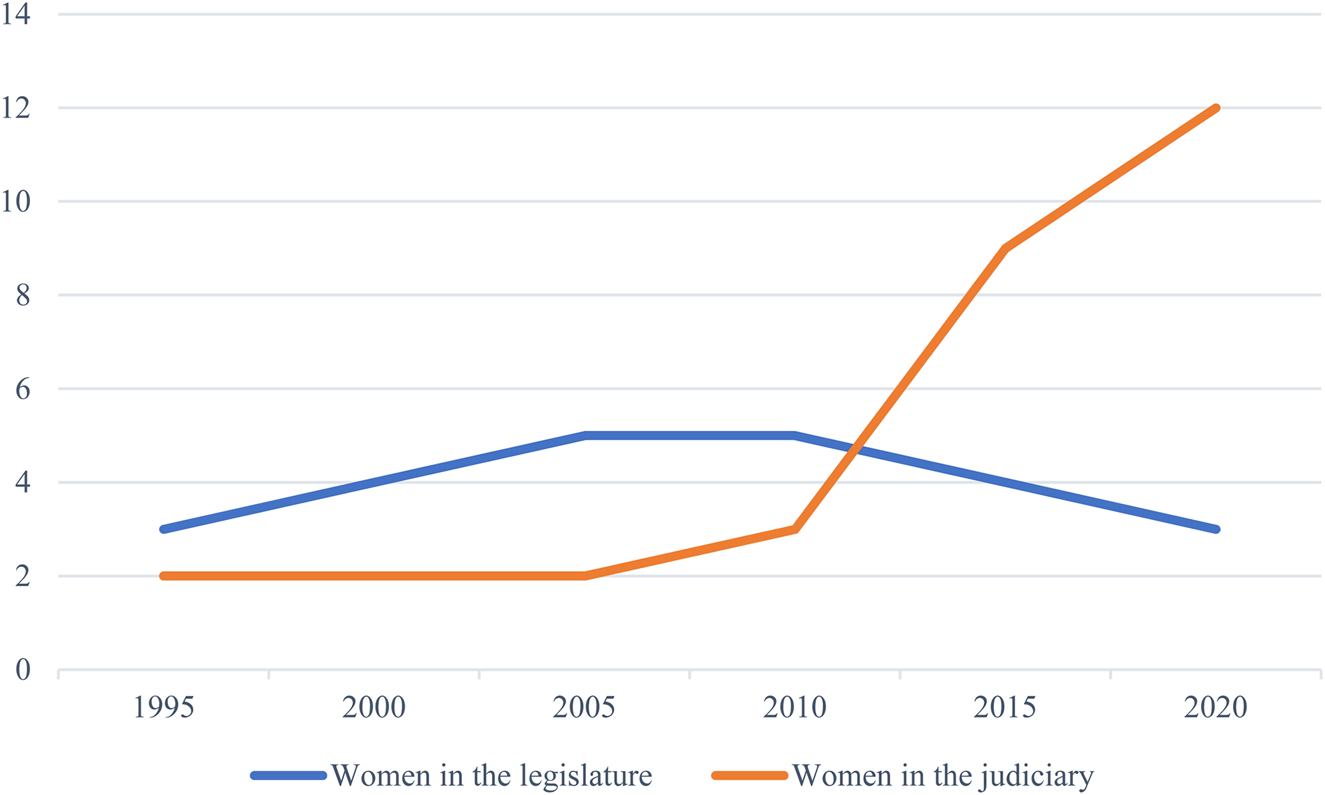

These stories are supported by numbers (see Table 1 and Table 2). The increase in the number of women in the Haitian judiciary coincides with an increase in the number of women graduates from the EMA. Since its creation, 256 magistrates have graduated from the EMA, of which 77 are women and 179 are men. The proportion of women EMA graduates increased from 11% in the first class of 1997–98 to 38% in the fifth class in 2012–14.Footnote 32 The last class in 2016 applied a gender quota in its recruitment strategy (more on that later), which boosted the proportion of women graduates to 50%.

Table 1. Women judges in Haiti

Table 2. Women in the magistrate school

Source: Ecole de la Magistrature, 2020.

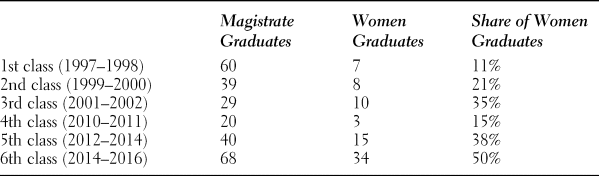

Figure 2 illustrates approximately how many of Haiti's current magistrates were appointed through the EMA and how many were directly appointed, divided by gender.Footnote 33 Today, 12% of magistrates are women, and 88% are men. The figure shows that 66% of all women magistrates were appointed through the EMA, while 34% of women were directly appointed. Just 25% of men magistrates were appointed through the EMA, whereas 75% of men were appointed directly. Hence, women still make up a minority of judges, but the majority of women judges are appointed through the EMA. Male judges, on the other hand, are overwhelmingly recruited through direct appointments.

Figure 2. Judicial appointments by gender. The horizontal axis refers to the percentage of women versus men judges. The vertical axis refers to the percentage of appointments through the EMA versus direct appointments.

The effects of a more transparent and merit-based appointment system of magistrates are likely exacerbated by the creation of more judicial posts. The number of posts increased from 660 in 2013 to 867 in 2020. This suggests less competition for posts and a demand for new recruits, which may have created incentives and opportunities for women to pursue a career in the judiciary. This pattern is consistent with findings from other contexts in which an expansion of the judiciary and a greater number of vacant posts are associated with increased opportunities for women to become judges (Arana Araya, Hughes, and Pérez-Liñán Reference Arana Aráya, Hughes and Pérez-Liñán2021; Crandall Reference Crandall2014; Escobar-Lemmon et al. Reference Escobar-Lemmon, Hoekstra, Kang and Kittilson2021).

In my source material for this study, including interview data, policy documents, and literature on judicial reform in Haiti (Berg Reference Berg2013; Cavise Reference Cavise2012; Democracy International 2015; Mobekk Reference Mobekk2016), I found no evidence that explicit arguments of gender balance in the judiciary motivated judicial reforms before 2014. The only area in which an explicit gender perspective was integrated was improving female court users’ access to justice, with a strong focus on combating gender-based violence (Democracy International 2015). This study is not exhaustive, however, and I cannot rule out that early judicial reform was not on any level motivated by possible gains in women's judicial representation. After all, these reforms took place beginning in the mid-1990s, during a period where women's access to decision-making was high on the international agenda. Still, my evidence suggests that gender balance was not a key priority in initial reforms.

Gender balance has only very recently become an explicit goal in judicial reform efforts. The EMA applied a gender quota of 50% in its recruitment strategy for the last class that graduated in 2016. This was part of a wider gender strategy, supported by the U.S. Agency for International Development and developed by the EMA and the CSPJ, that aimed to fulfill the 30% gender quota stipulated in the constitution (CSPJ 2018b). To get enough women to apply, representatives from the EMA led awareness-raising campaigns at law faculties, encouraging women who were finishing their law degrees to enroll at the magistrate school.Footnote 34 This new gender strategy will likely accelerate women's future entry into the judiciary as more magistrates graduate from the EMA. The gender strategy also implies that the CSJP must take gender representation into account when approving candidates for direct appointments. How to do this in practice is not yet clear. However, I argue that the increase in the number of women in the judiciary—which started several years earlier—is better explained by a change in appointment procedures than by the quota itself.

The effects of judicial reform on women's judicial representation may have worked in tandem with more structural developments. For instance, several of my interviewees claimed that more women are now studying law in Haiti. However, it is difficult to estimate the impact of such changes because of a lack of gender-segregated national data for law graduates or practicing lawyers. Besides, several scholars have debunked the trickle-up argument, and one should not attribute too much explanatory power to changes in educational opportunities, but rather see it in relation to other developments. As for changes in gender roles, little evidence suggests that any radical change has taken place in Haiti. The almost complete absence of women from the legislative sphere indicates that the most important changes have taken place at the institutional level in the judicial sphere.

In sum, although the introduction of women-friendly policies is often presented as the main cause of women's increased representation in conflict-affected societies (as stated in my first hypothesis), this is not the case for the Haitian judiciary. The increase in women in Haitian courts is more likely a by-product of judicial reforms aimed at creating a stronger and more independent judiciary. This supports my second hypothesis: that state-building efforts have introduced new merit-based appointment procedures through the creation of the magistrate school, which has helped women circumvent the predominantly male networks of power that previously excluded them.

CONCLUSION

Women's judicial representation is relatively overlooked by scholars studying women's representation. In particular, fragile and postconflict contexts are underexplored by scholars interested in explaining women's access to judiciaries, and the studies that do exist focus almost exclusively on women's access to higher judicial office. This study of women judges in the Haitian judiciary addresses this gap. Previous research on women's access to judiciaries urges us to look at women's participation in legal education, changes in gender roles, appointment procedures and legal traditions, gender quotas and other representative measures, and political will to explain women's access to judiciaries. By building on the literature on women's representation more broadly, including postconflict theory, we can draw several theoretical and empirical insights from this case study of the Haitian judiciary.

First, it shows how state building can contribute to gender equality, without necessarily having a pronounced gender agenda. Strengthening justice institutions by making recruitment procedures more meritocratic (through competitive examinations) and less politicized promotes not only judicial independence but also women's participation in decision-making. My findings from Haiti are consistent with previous scholarship on gender, recruitment, and meritocracy: recruitment based on transparency, objective merit-based criteria, and formal rules tends to benefit women's access to decision-making. Recruitment based on discretion, opaqueness, and informal patronage networks tends to benefit men (Bjarnegård Reference Bjarnegård2013; Rothstein Reference Rothstein, Stensöta and Wängnerud2018; Schultz and Shaw Reference Schultz, Shaw, Schultz and Shaw2013). For instance, in her study of the United States, Kenney (Reference Kenney2013a, 179) finds that more women become eligible for the judiciary when objective and transparent standards of merit are the criteria for appointment rather than cronyism and patronage. Boigeol (2018) attributes the feminization of the French magistracy to recruitment procedures based on competitive examinations. This article situates similar findings within a state-building context. Whereas the introduction of gender quotas is often presented as the main driver of women's increased representation in conflict-affected and fragile contexts, I find that more gender-neutral attempts at state building in the form of justice reform may open up opportunities for women to access the judiciary by simply rewarding academic achievements over powerful connections. The creation of the magistrate school in Haiti has helped women overcome serious barriers that more gender-targeted policy has not yet managed to do. This is an apprach to gender representation that has received little attention in the literature on state building in postconflict and transitioning contexts.

Second, this study sheds light on how women manage to make inroads into some state institutions while struggling to access others (Tripp Reference Tripp2015). This reflects the complexity of adopting and implementing different types of reform in fragile contexts. The Haitian case shows that while political openings and institutional ruptures can create opportunities for women to mobilize for better representation (adopting gender-friendly legislation), continued state fragility can also hamper attempts to actually follow through (implementing gender-friendly legislation). I suggest that political timing and donor priorities may explain why some types of reform succeed and others fail, and, consequently, why women manage to access some state institutions (the judiciary) while remaining marginalized in others (the legislature).

When it comes to political timing, who decides what and when is vital in a context like Haiti, where legislative processes are known to be extremely slow (Fatton Reference Fatton2000) and the effectiveness of reforms to a certain degree follows the trajectory of the country's political sitation and the political will of its leaders. For instance, the opening of the EMA under Aristide seemed to serve the president's initial aim of diminishing corruption and Duvalierist legacies in state insitutions. The 2007 law that reestablished the EMA was adopted during a period of relative stability and political inclusion under President René Préval, who urged the international community to focus on judicial reform and institutional support. His successor, Michel Martelly, campaigned on a promise of strengthening the rule of law and implementing the 2007 law package (which reestablished the EMA) during his first days in office (Berg Reference Berg2013). These flashes of political will and relative calm may have facilitated the adoption and implementation of important justice reform measures that also turned out to boost women's access to the judiciary. As previously noted, the timing of more targeted gender reforms was not ideal. The lack of commitment by the Haitian government to follow up on its promises is illustrative of how leaders of aid-dependent countries sometimes adopt women-friendly laws promoted by the international community without a true commitment to the women's cause (Bush Reference Bush2011; Hughes, Krook, and Paxton Reference Hughes, Krook and Paxton2015). A strong women's movement with capacity to hold decision makers accountable to their promises of gender-friendly reform is thus of vital importance in such contexts, but the Haitian women's movement's efforts have been severely hampered by underfunding, a lack of unity (Charles Reference Charles1995), few dedicated allies in government, human losses, and political instability.

Donor priorities matter, too. In states labeled “fragile” or “postconflict,” international actors tend to prioritize the justice sector in their efforts aimed at strengthening the rule of law (Lake Reference Lake2018) and to achieve stability, often to the detriment of the inclusion of underrepresented groups like women. Gendered approaches to international statebuilding tend to focus on “social” issues connected to women's special needs rather than gender power relations in state institutions (Castillejo Reference Castillejo, Chandler and Sisk2013, 30). In Haiti, the attention has been overwhelmingly on combating gender-based violence. While scholars have long predicted a decoupling of law and practice in fragile state settings (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Boli, Thomas and Ramirez1997), the absence of a strong state may also create opportunities for NGOs and international organizations to step in and assume responsibility for prioritized areas of local governance, such as the justice sector (Lake Reference Lake2018). In Haiti, this has opened up space for the international community to take charge of the operation of the magistrate school and the CSPJ, which perhaps would not be possible in a stronger state. The lack of state capacity may constitute less of a problem for the implementation of judicial reform than other types of reform in Haiti because donors prioritize the justice sector.

It should be noted that judicial and gender reform are not entirely decoupled. Although meritocratic and transparent recruitment procedures have proved to be more important for increasing women's judicial representation in Haiti, gender-targeted measures like gender quotas may work within already established meritocratic systems, as witnessed during the last recruitment to the EMA. One should not ignore the potential symbolic effects of gender reform either, even when less successful, as it puts gender balance on the agenda and sends an important message about transforming gender roles and women's rights to participate in decision-making in highly patriarchal societies. The implementation of gender quotas in the EMA's recruitment strategy shows that in the absence of government actions, quotas “on paper” can function as a guiding principle for other institutions and actors to work for increased gender balance. Such symbolic effects are potentially important, but also hard to measure, and would make an interesting topic for future research. At the same time, the use of gender quotas in judiciaries remains controversial (Malleson Reference Malleson2009, Reference Malleson2014). Some see quotas as giving preferential treatment to “unqualified” women at men's expense, despite solid evidence to the contrary from the political field (see Franceschet and Piscopo Reference Franceschet, Piscopo, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012; Josefsson Reference Josefsson2014; Murray Reference Murray, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopo2012; Nugent and Krook Reference Nugent and Krook2016; O'Brien Reference O'Brien, Franceschet, Krook and Piscopop2012). This study shows that less explictly gendered measures can play an important role in helping women access the judiciary in state-building contexts that avoids some of the controversies and challenges surrounding gender quotas: if only access to judicial office is based on fully transparent and formal criteria, women will find a way in. This resonates with the words of the late U.S. Supreme Court justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg: “I ask no favor for my sex. All I ask of our brethren is that they take their feet off our necks.”Footnote 35

On a final note, it is important to acknowledge the often highly problematic role that the international community has played in Haiti. At times, international donors have undermined Haitian state institutions and created a culture of aid dependency (Schuller Reference Schuller2017). International peacekeepers have also exposed the people they were supposed to protect to a cholera epidemic (Katz Reference Katz2016) and sexual exploitation (Peltier Reference Peltier2019). Still, the relative success of judicial reforms, in terms of boosting women's judicial representation, points to the important role the international community can play in helping women participate in shaping the future of Haiti by focusing on strenghtening Haitian institutions. The operation of the magistrate school (EMA)—and the continued influx of women to the judiciary—relies on continued international support, as the Haitian government has shown limited will and capacity to create a more independent judiciary. Simultaneously, this makes the functioning of the EMA vulnerable to external shocks and changing donor priorities. Many Haitians and international commentators welcomed the departure of the UN peacekeeping mission in 2019 because of its problematic history and its threat to Haitian state sovereignty. Still, the dramatic downscaling of an organization that has had justice support as one of its main pillars may have serious consequences for the development of the justice sector. The domestic political context complicates things further, as the last class of magistrates of 2019 had to be postponed because of serious political unrest and widespread violence that year. This points to the complexety of women's representation in conflict-affected states that are still plagued by state fragility and how the opportunity structures found in such contexts may fluctuate dramatically.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit [https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X21000398]