Introduction

North America is a hotspot of ancient aquatic vertebrate diversity. All but one of the classic ancient lineages of ray-finned fishes (Polypteridae; e.g., Near et al., Reference Near, Dornburg, Tokita, Suzuki, Brandley and Friedman2014) are found on the continent, and at least three of these are presently entirely confined to North America (gars, Bowfin, Hiodon Lesueur, Reference Lesueur1818; Grande and Bemis, Reference Grande and Bemis1998; Hilton, Reference Hilton2003; Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2008; Grande, Reference Grande2010). Acipenseriformes, which currently comprises 27 species of sturgeons and the Paddlefish and includes some of the largest living freshwater fishes (Huso Linneaus, Reference Linnaeus1758; see Berg, Reference Berg1948) is the most diverse and geographically widespread of the major ancient ray-finned fish clades. Despite the status of this clade, the evolutionary history of Acipenseriformes remains poorly understood. The anatomy, fossil record, and interrelationships of this clade have been the subject of numerous detailed morphological studies (Grande and Bemis, Reference Grande and Bemis1991; Bemis et al., Reference Bemis, Findeis and Grande1997; Grande and Hilton, Reference Grande and Hilton2006; Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2006; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Brinkman, DeMar and Wilson2020; During et al., Reference During, Smit, Voeten, Berruyer, Tafforeau, Sanchez, Sten, Verdegaal-Warmerdam and van der Lubbe2022).

Despite the large number of specialized features unique to Paddlefish and sturgeons, the available fossil record for these fishes indicates the phenotype in Acipenseriformes has remained remarkably unchanged over perhaps 100 Myr (Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Brinkman, DeMar and Wilson2020). Unfortunately, gaps in the fossil record of Acipenseriformes for key intervals like the aftermath of the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction 66 Ma have obscured whether this pattern of phenotypic conservatism is a biological reality or an artifact of sampling (Grande and Hilton, Reference Grande and Hilton2006; Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2006; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018; Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2022).

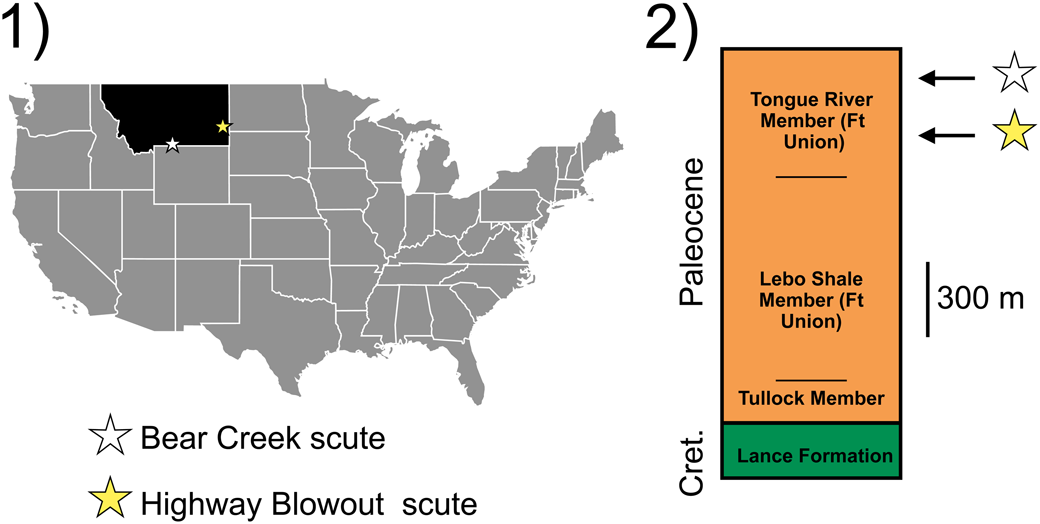

Here, I describe two records of sturgeons from the 7 Myr following the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction in western North America (Fig. 1). These lateral osteoderms demonstrate the presence of large (>1.5 m) sturgeons in early-middle Paleocene freshwater ecosystems. In turn, they extend the record of large (>1 m) body size in Acipenseriformes back by 60 Myr and imply that the high degree of body size disparity observed in this clade relative to other vertebrates (Rabosky et al., Reference Rabosky, Santini, Eastman, Smith, Sidlauskas, Chang and Alfaro2013) is a consistent pattern in their evolutionary history.

Materials

Repository and institutional abbreviation

YPM, Yale Peabody Museum, New Haven, Connecticut, USA.

Systematic paleontology

Actinopterygii Cope, Reference Cope1887

Acipenseriformes Berg, Reference Berg1940

Acipenseridae Bonaparte, Reference Bonaparte1831

Acipenseridae morphotype A

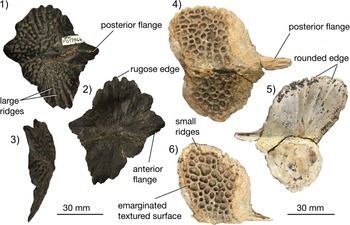

Figures 2, 3

Figure 1. Locality and horizon of the new sturgeon material: (1) map of the United States showing localities where sturgeon records reported in this paper were recovered; (2) simplified stratigraphic column of the Cretaceous-Paleogene in Montana showing horizons from which sturgeon material reported in this paper was recovered.

Occurrence

Layer #3, Eagle Mine near Bear Creek, Carbon County, Montana (Bear Creek Local Fauna, Fort Union Formation, Tiffanian-Clarkfordian, 61.2–56.6 Ma; Barnosky et al., Reference Barnosky, Holmes, Kirchholtes, Lindsey, Maguire, Poust, Stegner, Sunseri, Swartz, Swift and Villavicencio2014, fig. 1). Precise coordinates are available to qualified researchers at YPM.

Description

YPM VPPU 17066 consists of an exquisitely preserved, isolated dermal scute (Fig. 2.1–2.3) assignable to a large acipenserid sturgeon (Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2006; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Thieren et al., Reference Thieren, Wouters and Van Neer2015; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Brinkman, DeMar and Wilson2020). The size and shape of the scute allow assignment of YPM VPPU 17066 to the sturgeon crown group Acipenseridae because the closest fossil relatives of this lineage lack large lateral scutes (e.g., Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2006). The scute, which represents the best record of an acipenseriform from the Bear Creek Local Fauna, comes from the middle portion of the lateral row based on its dorsoventral asymmetry and median ridge size (Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011), which produce a slight posterior slant for the scute in lateral and medial views (Fig. 2.1, 2.2).

Figure 2. Anatomy of the new sturgeon specimens of Acipenseridae morphotype A: (1–3) YPM VPPU 17066, Bear Creek Site, Montana: (1) lateral view; (2) medial view; (3) anterior view; (4–6) YPM VPPU 16646, Highway Blowout Site, Montana; (4) lateral view; (5) medial view; (6) dorsal view.

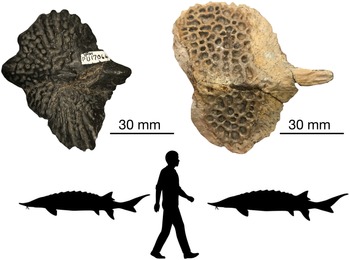

The external surface is ornamented with unorganized deep pitting and several large ridges that radiate from the defined central ridge and produce a rugose outline. These ridges are much larger than those seen in extant sturgeons, e.g., Acipenser spp. (e.g., Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Thieren et al., Reference Thieren, Wouters and Van Neer2015). Pitting is not confined to the center of the external surface of the scute and variously reaches the borders of this bone (Fig. 2.1, 2.2). Size estimation using the lateral scute maximum equation of Thieren and Van Neer (Reference Thieren and Van Neer2016) using the dorsoventral maximum height of YPM 17066 (70 mm) provides a total length of 1.650 m for YPM VPPU 17066 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Size comparison of the two new sturgeon records of Acipenseridae morphotype A: Bear Creek sturgeon (left); Highway Blowout sturgeon (right). Silhouette is a 1.85 m tall man.

Material

YPM VPPU 17066, a complete lateral scute.

Remarks

YPM VPPU 17066 is identifiable as the lateral dermal scute of an acipenserid.

Occurrence

Highway Blowout Site, Fallon County, Montana (Tongue River Member, Fort Union Formation, Tiffanian-Clarkfordian, ~62–60 Ma; Peppe et al., Reference Peppe, Johnson and Evans2011). Precise coordinates are available to qualified researchers at YPM.

Description

YPM VPPU 16646 is another complete dermal scute from a large acipenserid fish (Fig. 2.4–2.6). This specimen is slightly larger than YPM VPPU 17066 and shows a very different set of features. Although the dorsoventral asymmetry of YPM VPPU 16646 demonstrates that it comes from the lateral scute row, the specimen is strongly angled along its dorsoventral midline (Fig. 2.4). This produces distinctive dorsal and ventral faces. The form of ornamentation on YPM VPPU 16646 is also markedly different from YPM VPPU 17066 and more closely resembles the ornamentation of extant sturgeons like Acipenser spp., Huso spp., Scaphirhynchus spp., and Pseudoscaphirhynchus spp. (Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Thieren et al., Reference Thieren, Wouters and Van Neer2015) and extinct crown-group acipenserids, e.g., †Anchiacipenser acanthaspis Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018. Although the size of individual pits on YPM VPPU 16646 is larger than most crown group sturgeons (Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Thieren et al., Reference Thieren, Wouters and Van Neer2015; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018) and stem-group taxa from North America (Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018), YPM VPPU 16646 shares with these forms reduced radiating ridges and pitting ornamentation that is widely separated from the scute border by a relatively smooth surface bearing small radiating ridges (Fig. 2.4–2.6).

YPM VPPU 16646 is unusual in that it bears a large flange directed toward the posterior end of the body. Although some extant sturgeon lateral scutes show small posterior spines (Thieren et al., Reference Thieren, Wouters and Van Neer2015), the posterior flange on YPM VPPU 16646 is two-thirds of the anteroposterior length of the main body of the osteoderm. Another odd feature of YPM VPPU 16646 is the rounded outline of the main body of the scute. In most crown sturgeons, the lateral scutes have main bodies that terminate dorsally and ventrally at distinct apices, forming a rhomboid shape in lateral and medial views. Size estimation using the lateral scute maximum equation of Thieren and Van Neer (Reference Thieren and Van Neer2016) using the dorsoventral maximum height of YPM VPPU 16646 (= 75 mm) gives a total length of 1.653 m for the Highway Blowout acipenserid (Fig. 3).

Material

YPM VPPU 16646, a complete lateral scute.

Remarks

YPM VPPU 16646 is identifiable as the lateral dermal scute of an acipenserid.

Discussion

Eight extant sturgeon species are currently found in North America, but the fossil record of the crown group on the continent stretches back to the Cretaceous (Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2006; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Brinkman, DeMar and Wilson2020). Although living sturgeons in the genera Acipenser Linneaus, Reference Linnaeus1758 and Huso are the largest known freshwater fishes (e.g., Berg, Reference Berg1948; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011), most of the published fossil record of the crown clade is comprised by relatively small (~1.0 m or less) species (Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2006; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Brinkman, DeMar and Wilson2020). The ancient ages of the two lineages in the crown group are known to include giant species. For example, various time-calibrated molecular phylogenies suggest that giant species, e.g., Acipenser transmontanus Richardson, Reference Richardson1836 and Huso spp., last share common ancestry with other sturgeons varying between 8 and >50 Ma (Peng et al., Reference Peng, Ludwig, Wang, Diogo, Wei and He2007; Luo et al., Reference Luo, Li, Zhao, Zhao, Ludwig and Peng2019; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Yang, Liu, Chen and Li2020). These estimated ages imply long ghost lineages leading to extant giant sturgeons.

The two new sturgeon specimens, although not complete enough to justify naming new species, represent giant acipenserids from two different geological units in the Paleocene of the American West. Both specimens are within the upper size bracket for Acipenseridae (Thieren et al., Reference Thieren, Wouters and Van Neer2015; Thieren and Van Neer, Reference Thieren and Van Neer2016), stretching the record of large size in this clade back by at least 60 Myr to the recovery period following the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction. Although their assignment to subclades in Acipenseridae is limited by the wide variability of osteoderm shape in sturgeons (Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2006; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Brinkman, DeMar and Wilson2020), both the Bear Creek and Highway Blowout scutes belong to pan-acipenserids, which are characterized by the presence of distinctive dermal osteoderms (Hilton and Grande, Reference Hilton and Grande2006; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Murray, Vernygora and Currie2018; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Brinkman, DeMar and Wilson2020).

The high degree of body size disparity in extant sturgeons (Rabosky et al., Reference Rabosky, Santini, Eastman, Smith, Sidlauskas, Chang and Alfaro2013) contrasts with their status as a living fossil lineage, i.e., a long-lived, species-poor clade that shows little phenotypic change from ancient fossil relatives (Gardiner, Reference Gardiner, Eldredge and Stanley1984; Grande and Bemis, Reference Grande and Bemis1991; Bemis et al., Reference Bemis, Findeis and Grande1997; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011). A similar pattern of proportionally high variation in body size relative to species diversity has also been documented in latimeroid coelacanths, which include the freshwater-brackish clade †Mawsoniidae (Cavin et al., Reference Cavin, Piuz, Ferrante and Guinot2021).

Finally, the new large-bodied sturgeon records add to the growing body of evidence that ancient freshwater fish assemblages from the Paleocene and Eocene of North America contained numerous large-bodied clades with different body plans (e.g., Grande and Bemis, Reference Grande and Bemis1991, Reference Grande and Bemis1998; Grande, Reference Grande2010; Hilton et al., Reference Hilton, Grande and Bemis2011; Brownstein, Reference Brownstein2022). The suction-feeding style of sturgeons (e.g., Carroll and Wainwright, Reference Carroll and Wainwright2003) represents a unique component to these assemblages, which are already known to include durophagous and macropredatory gars with shortened to longirostrine skulls (Grande and Bemis, Reference Grande and Bemis1998; Grande, Reference Grande2010; Brownstein, Reference Brownstein2022), filter-feeding paddlefishes (Grande and Bemis, Reference Grande and Bemis1998), and large, predatory osteoglossiform fishes with the characteristic rasping device that gives the clade its name (Forey and Hilton, Reference Forey, Hilton, Elliot, Yu, Maisey and Miao2010; Hilton and Lavoué, Reference Hilton and Lavoué2018). In turn, the specimens described in this contribution indicate a legacy of giant acipenserids in Paleocene North American ecosystems in need of further discoveries to be fully revealed.

Acknowledgments

I thank D. Brinkman, G. Watkins-Colwell, and V. Rhue for access to the ichthyology and palaeoichthyology collections of YPM. This research was supported by the Yale Undergraduate Richter Summer Fellowship through Pierson College. I thank the editor A. Murray, D. Brinkman, and an anonymous reviewer for their comments, which greatly improved this manuscript. Sturgeon silhouettes used in Figure 3 are in the public domain (http://phylopic.org/). This paper is dedicated to my parents D.I. Brownstein and L.R. Tannebaum, who first introduced me to sturgeons as the tastiest smoked fish.