A lawyer, a diplomat, twice a papal nuncio in Spain, a powerful and shrewd cardinal of the Curia where he held many important offices under Pope Paul v, Gian Garzia Millini (or Mellini) was also the secretary to the Congregation of the Holy Office.Footnote 1 And it was in this capacity that on 11 January 1614 he wrote to the inquisitor in Bologna:

A printed text was sent to this Holy Office, Lettera di N. ad un amico nella quale brevemente racconta le cause perché egli sia partito dalla religione romana [Letter from X. to a friend in which he briefly explains why he has left the Roman religion], that contains a summary of all modern heresies against the holy Catholic faith, as you will be able to see. And this Letter was distributed to many by a heretic merchant from the Palatinate, who came to the fair in Bolzano, and he had a pile of copies, on top of which was written: Pro fratribus nostris Neapolitanis [For our Neapolitan brethren]. And it is believed that many copies might have been sent to several Italian cities, because of packets of letters and merchants going around to market fairs and other places.Footnote 2

The Letter, of which Millini also sent a transcript to his correspondent, was believed until recently to be lost. However, an original copy, belonging to a private collection, has lately appeared on the antiquarian market. The booklet is printed – anonymously, and without location – in four pages, in octavo, on laid paper but without a visible watermark. This is the only exemplar known today, despite (at least according to Millini) an entire ‘pile’ of them reaching Italy. A small success, therefore, for the Roman Holy Office, committed to patrolling the borders to stop ‘this plague of books … that could infect these our parts of Italy’, as Cardinal Bellarmine put it to the inquisitor of Modena on 26 July of that same year.Footnote 3 He encouraged him to to be vigilant and zealous ‘at least to extirpate [the plague] from those places where we can’.Footnote 4

The inquisitorial correspondence shows that in the early 1610s, via the Brenner, Venice and the Tyrrhenian sea ports, heretical booklets and pamphlets were still, by clandestine means, reaching Italy, enabling what was by this date only a feeble current of Protestant proselytism.Footnote 5 This trade was also intended to support heterodox congregations, at least those few which had survived more than half a century of watchful Catholic surveillance and repression. Apparently one such tiny conventicle still existed in the Kingdom of Naples, as we learn from Millini's letter. It is unlikely that this was connected with the heterodox spiritualist tradition inaugurated in Naples by Juan de Valdés in the 1530s;Footnote 6 it is also improbable that it was the remnant of a continuing presence of Reformed Waldensians in Apulia and Calabria: they had been wiped out over fifty years before.Footnote 7 More realistically, this dissenting community was probably the result of the development of new maritime connections between the Mediterranean and the North Sea, and of the arrival in Southern Italy of ships from England and the Netherlands. A Note of the books burned in Naples on the festivity of St Peter and St Paul in the year 1610 indicates the presence of catechisms and biblical texts translated into Italian, some of them recently printed, others probably handed down from previous generations.Footnote 8 In the 1620s and ’30s a concerned archbishop of Naples still ordered raids and requisitions of books in the city's port.Footnote 9

Whatever its identity, it is only Millini's letter that makes an explicit reference to an actual dissenting group congregating at the foot of Vesuvius in the early 1610s; and the cardinal himself – at least according to the sources available to usFootnote 10 – did not even believe it necessary to inform the archiepiscopal vicar of Naples of its existence, for he held the office of inquisitor. Millini also did not tell the vicar of the arrival in Italy of the Lettera di N. ad un amico (see Figure 1). Nor indeed did he tell him about a longer text, also mentioned in his letter: a forty-eight-page booklet, entitled Ragionamento in materia di religione accaduto novamente tra due amici italiani passando da Roma a Napoli l'anno 1613 [Debate in matters of religion that recently has taken place between two Italian friends whilst they were going from Rome to Naples in the year 1613]. This too was a text full of ‘many pernicious heresies’: this is why Millini had already written about it in October 1613 to the inquisitor of Modena.Footnote 11 The Ragionamento was not included in the Index of prohibited books until 1624.Footnote 12

Figure 1. Lettera di N. ad un amico nella quale brevemente racconta le cause perché egli sia partito dalla religione romana (c.1612). Private Collection. Reproduced by kind permission.

The brief Lettera di N. ad un amico (see Appendix 1) is a folio of 20.4cm x 15.1cm, with a cut of 2cm on the top. A Lutheran document, it was undoubtedly printed in Germany shortly before Millini's letter; the cardinal was able to announce its discovery thanks to the unearthing of one of the usual channels of Protestant propaganda, either those of trade and contraband, or those of active colportage. It is not impossible to think that its title, Lettera, was chosen as a reference to the religious turmoil that had shaken Venice in the aftermath of the Interdict crisis of 1606, which led to a real ‘war of words’.Footnote 13 Many pamphlets published in those days had used the rhetorical device of the ‘letter’: for example the 1606 Lettera di Eulogio teologo romano [Letter of Eulogy, Roman theologian], and the Letter of a baker of Boulogne sent to the pope, versions of which, in English, Dutch and French (but not in Italian), have survived.Footnote 14 Even if they did not contain any explicit reference to Venice's troubles, we can be sure that the primary destination of many texts of Protestant propaganda – often stemming from the book market of Frankfurt, or coming from Antwerp (via Paris and Lyon) – was the Republic of Venice. From there, by means of several avenues of circulation, they reached the rest of the peninsula. This was something well known to Rome; Cardinal Pompeo Arrigoni (Millini's predecessor), for example, had frequently warned the inquisitors of northern Italy, and in particular those of Florence and Modena.Footnote 15

Recent works on religious propaganda in Counter-Reformation Italy have shown a constant, albeit weak, attempt at Protestant proselytism in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.Footnote 16 At the very end of the so-called ‘Italian Reformation’, between the 1560s and 1570s, quite a few Reformed publications written by Italian exiles in the Valtellina and in Switzerland had reached the peninsula: these were mostly underpinned by the hope of involving Italy in the confessional struggles of the French wars of religion.Footnote 17 Such ambitions were soon to be frustrated, and by the late 1580s, with the first generation of Italian Protestant exiles disappearing, a calm before the storm was perceivable within Italian Protestant dissent. A storm was certainly to come over the Venetian Interdict crisis of 1606: some – in Venice and abroad – believed that the Republic, having broken off relations with the pope, might turn to Protestantism, or at least might allow Protestant congregations to function within the city. Venice was soon flooded with pamphlets.Footnote 18 The authors of this initiative found a spokesperson in the theologian and jurist Paolo Sarpi, the protagonist of the struggle for Venice's autonomy. Books and preachers involved in this episode were distinctly Reformed, and the product of an international network of Calvinists that encompassed French Huguenots, Dutch merchants, English preachers and ambassadors, Germans from the Palatinate, and Italian exiles in Switzerland. By the mid-1610s, however, none of the expected outcomes had come to pass: Venice was solidly back in the Catholic fold. Of course, a sprinkling of Protestant writings, combined with the presence of Reformed merchants and travellers in the peninsula, kept appearing in Italy, particularly during the Thirty Years War, but this was less and less the result of a concerted enterprise, and more the product of individual and isolated actions.Footnote 19

All the scholarship on the subject of Protestant propaganda in Italy in this period has shown that at its heart were the networks of international Calvinism.Footnote 20 The publications so far studied are clearly Reformed in their theology and provenance. Until now, scholars have believed that organised Lutheran Italian proselytism had most definitely concluded decades before our story: Lutheran activism would be unheard of at the time of the publication of the Lettera di N. ad un amico. It is therefore the first purpose of this article to account for the surprising existence of a series of Lutheran propaganda texts directed at Italy in the 1610s, and to investigate their authorship. But further questions are also in order. Who was behind this ambition to convert Italians to Lutheranism? Was this a concerted plan, or just a one-off? What were the hopes of their authors? And, were the worries of the Inquisition in any way justified? Was there any space for a ‘Lutheran option’ in early seventeenth-century Italy?

II

In those same weeks when he was expressing concern about the Letter and the Ragionamento, Cardinal Millini urged the inquisitor of Florence to watch out for another booklet that had recently ‘come to light’ in Kempten, a Lutheran town in Allgäu, between Münich and Konstanz.Footnote 21 Millini explained that this was entitled Tractatus brevis continens decem principia doctrinae christianae [Brief treatise containing ten principles of Christian doctrine], ‘whose author is Antonio Albizzi, a Florentine resident in Kempten, and is full of heresies’.Footnote 22 Only ten days later, the cardinal also wrote to the inquisitor of Modena, adding some details concerning the author of the Tractatus: a ‘Florentine nobleman … sometime counsellor to some princes in Germany, that has since turned heretic’.Footnote 23

Further, in that same letter, Millini had also explained that ‘We have got news that in Tübingen an heretical catechism was printed in the Italian language, and many copies of it have been sent to Italy, and especially to Venice.’Footnote 24 On 16 October 1613 an internal document of the Holy Office had already clarified that such news had been received directly from Augsburg by Cardinal Bellarmine.Footnote 25

The concentration of Protestant publications around 1613 (the Letter, the Tractatus, the Ragionamento, in addition to an earlier Lutheran Catechism) can perhaps be explained by the sharp turn in religious policy that Emperor Mathias had imposed on his territories after he succeeded his brother on 20 January 1612. Not least because of the weakening of France after the death in 1610 of Henry iv, the new emperor was able to reposition the staunch Catholic credentials of the House of Habsburg: the previously moderate Habsburg policy had been very close to the position of the author of the Tractatus and of the Letter. After 1612, a reinvigorated season of confessional conflict was opening up. It may not be a surprise, then, that Antonio degli Albizzi, an Italian who for thirty years had been in the service of the Habsburg family, might have thought that this was the time for him to act, and to oppose the new Counter-Reformation fervour: he wanted to do something at least for his homeland, one he had left some thirty-five years previously.

To better understand the anomaly of such Lutheran propaganda in Italy it is first necessary to consider the ‘heretical Catechism in the Italian language’ published in Tübingen in 1609. The circulation of this text worried the inquisitors, albeit in December 1610 the Holy Office was relieved to learn from Venice that no copy had yet turned up in the city.Footnote 26 There is no doubt that this was a new reprint of the Italian version of Luther's 1529 Kleiner Catechismus, translated by the Istrian priest Antonio D'Alessandro (also known as Antonio Dalmata), and originally published in Tübingen in 1562 thanks to Pier Paolo Vergerio (1498–1565) by the widow of the printer Ulrich Morhart.Footnote 27 Morhart had already printed a few polemical pamphlets on behalf of Vergerio – the former bishop of Capodistria (today Koper, in Slovenia) turned virulent Lutheran polemicist – and in 1563 a complete collection of his works had also appeared.Footnote 28 In that same year Vergerio also encouraged the publication of two editions of the Beneficio di Cristo, the key text of the Italian Reformation: one in Italian, the other translated into Croatian (and printed both in Latin and Glagolitic characters, in two different booklets), in a translation by D'Alessandro and his collaborator Stefano Consul, another exiled Istrian priest.Footnote 29

Between 1561 and 1565, many Protestant books had actually appeared in Italian, Slovenian and Croatian thanks to cooperation between Vergerio and Primož Trubar, the father of the Slovenian Reformation and of the modern Slovenian language: all this was happening in a printing workshop set up in Urach (Tübingen) by the Styrian baron Hans von Ungnad, a counsellor to the duke of Württemberg.Footnote 30 The 1562 edition of Luther's Small catechism, overall a faithful translation of the text, contains a curious typo: the title reads Catechismo piocciolo, instead of piccolo (or even picciolo) as it should. When the booklet was reprinted in Tübingen in 1588 (in thirty-two pages, with numeration only on the recto), the typo was not amended, perhaps a sign of the loss of any real knowledge of Italian among these Lutheran circles. According to the Edit16 catalogue, this 1588 edition can be attributed to Ulrich Morhat's stepson, Georg Gruppenbach, who – having inherited the family business – in 1585 and again in 1587 also published an Italian version of Luther's Large catechism, in a translation by Solomon Swiggert, sometime Lutheran minister in Constantinople.Footnote 31 Gruppenbach had been for some years the unofficial printer to Tübingen's evangelical Church: he died in 1610, after having gone bankrupt in 1606. His entire warehouse was bought by a bookseller from Frankfurt, Johann Berner, but it is not known whether he also purchased the printing equipment.Footnote 32

Georg Gruppenbach was not therefore the printer of the 1609 Italian reprint of Luther's Small catechism; of this edition only three copies are preserved today, one in the British Library, one in the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, and one in the National and University Library in Strasbourg. Many years had passed between the 1588 edition and that of 1609, years of silence on the Italian Lutheran front. But some curious links can be found. First, a copy of the 1588 Catechism now at the Österreichische Nationalbibliothek in Vienna (ms 14.L.82) has in its conclusion a short gothic inscription that dates its purchase to 1609 (the same year of the edition here examined). Secondly, a similar ornament with a grotesque mask was placed at the end of the 1588 Italian edition (see Figure 2), as well as on the Lettera di N. ad un amico (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Martin Luther, Catechismo piocciolo (1588), detail. Reproduced by kind permission of Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Available on GoogleBooks.

Figure 3. Lettera di N. ad un amico, detail.

Although the images of the grotesque mask are copies, the engraving is not the same, as can be seen by the differences among the curls at the top, to mention just one contrast; both of them were inspired by the figure of the Mask of Truth. The issue of attributing this ornament to a specific printer is further complicated by the fact that (in a smaller format, and therefore also as the result of a further engraving) the grotesque mask appears to have been in the typographic tool-kit of another Lutheran printer, Johann Steinmann, certainly a member of the Steinmann publishing house who had worked in Leipzig between 1571 and 1590. Unfortunately, no Johann Steinmann appears in the Short title catalogue of German books preserved at the British Library, nor in the Universal short title catalogue: they instead mention Hans Steinmann (active until 1588), followed by his heirs until 1590, and a Tobias Steinmann, active in Leipzig between 1585 and 1600.Footnote 33 We are only aware of Johann Steinmann because in 1580 he printed in Latin cum gratia et privilegio the 800 pages of the Lutheran Concordia, a crucial collection of the founding documents of Lutheranism that was to be reprinted many a time in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.Footnote 34 It was also published in Dresden, in German, in the same year. Between pages 333 and 337 of Steinmann's Latin Concordia appears a lavishly illustrated reprint of Luther's Catechismus minor; at the bottom of its final page the grotesque mask appears again.

Any involvement by Steinmann in the 1609 reprint can probably be discounted. This edition was in all likelihood published by a German printer (perhaps one from Tübingen, as Millini suggests), but he was clearly unable to amend ‘piocciolo’ to the correct piccolo or picciolo. The printer did not hesitate instead to make explicit the name of Martin Luther both on the frontispiece of his edition, and in the running heads, something that surely did not make the book very exportable to Italy. The primary use for this catechism was probably for some small Italian congregation in Germany or nearby. Unfortunately, there is no further evidence concerning either the publisher and the promoter of this edition, or its final destination. The 35-page-long booklet, numbered both on the recto and the verso, was a simple translation of Luther's text, albeit without his introduction. It included brief comments on the ten commandments, the Creed, the Pater Noster, summaries on the sacraments of baptism, confession and the eucharist, and morning and evening blessings; as a conclusion, there are ‘certain passages of the Scriptures, selected for various orders and conditions of men, wherein their respective duties are set forth’.Footnote 35

The content, format and language choices of the Letter show instead that Italy was its intended destination. It is of course perplexing that its anonymous author still believed that in the early seventeenth century the Lutheran cause in Italy still had traction. Was this a simple individual action of Christian witness, or the result of an organised plan for proselytism? There is no information about the author or where the Letter was printed. But everything points to the Florentine exile Antonio degli Albizzi, author of the Tractatus printed in Kempten in 1612, whose distribution in Italy had been very much feared by Cardinal Millini.

III

Antonio degli Albizzi was born in 1547 to an illustrious Florentine patrician family which had long fought against the Medicis.Footnote 36 He studied logic and law in Venice and Padua under Carlo Sigonio, before moving to Bologna and then to Florence, where he attended Pietro Vettori's lectures on ethics. He finally completed his education in Pisa, where in 1566 he became ‘regent’ of the local Accademia degli Alterati. Still young, Antonio was the author of writings on Dante,Footnote 37 of Carnival poems and of a biography of Pietro Strozzi (a leading opponent of the Medici), which clearly points to Albizzi's own political persuasions.Footnote 38 Nevertheless, he was soon named ‘consul’ of the Accademia Fiorentina, and was called to give a lecture in the presence of Johanna of Habsburg, grand-duchess of Tuscany, on Aristotle's Rhetoric.

Thanks to this connection, in 1576 he moved to the Habsburg lands, and into the service of Andreas von Habsburg (1558–1600), who – having just turned eighteen – had recently been made cardinal by Gregory xiii. Andreas, margrave of Burgau, was the child of a morganatic marriage between Philippine Welser, daughter of a rich family of Augsburg merchants, and Ferdinand ii, archduke of Further Austria and count of Tirol, brother to Emperor Maximillian ii. Andreas was soon appointed coadjutor bishop of Bressanone (Brixen) in 1580, commedatory abbot of Murbach in 1587 and bishop of Konstanz in 1589, all of which he held in plurality.Footnote 39 The young cardinal was rarely resident in his benefices, and did not show much Tridentine zeal.Footnote 40 Actually, he was mostly occupied as governor of Further Austria, of Carinthia and on one occasion of Alsace. And it was in these political roles that Andreas found Albizzi to be his faithful right-hand man: Antonio acted as his secretary, counsellor and camerarius aulicus. A close bond was surely established between the two, proof of which can be found in the fact that the cardinal's two illegitimate children, born respectively in 1583 and 1584, were given the names Hans Georg and Susanna degli Albizzi: the Florentine aristocrat had taken on their official paternity, and responsibility for their education.Footnote 41

Albizzi was soon named by Andreas as governor of Klausen (today Chiusa di Val Gardena, near Bressanone, in Italy), but was later sent by the cardinal to be a commissary of the Habsburg duchy of Carniola (Slovenia). There Albizzi administered the justice system for five years. And it was probably in Carniola – where Primož Trubar had been superintendent of the Lutheran church, and that still knew a significant Lutheran presence – that around 1585 the cautious and mysterious conversion of Antonio Albizzi to Protestantism took place. His conversion was prompted by an illness: even better, according to his biographers, it occurred because of ‘the reading of Paul's letters to the Romans and the Galatians’ to him by a Jesuit.Footnote 42

Under the protective wing of Cardinal Andreas (or perhaps even with his complicity), Albizzi – the legal father of Andreas's children – started a long and serene nicodemitic life: one that undoubtedly brought him, and without much drama, to attend the Catholic ceremonies and rites celebrated by his protector. In his theological works, written more than twenty years later, there would be no mention or condemnation of religious simulation. These were actually very different days from those in which John Calvin's Exhortation to martyrdom was written; indeed, not even among Italian Protestant dissenters did many seem willingly to embark on such a path.

There is very probably a key Slovenian connection informing Albizzi's Lutheran experience: by 1585 Primož Trubar was already in Germany, where he collaborated with Pier Paolo Vergerio and baron von Ugnad in Urach's printing shop. But before that, between 1553 and 1561, Trubar had served as the minister of Kempten, the small neglected town where Antonio degli Albizzi would find refuge in the later years of his life.

Albizzi was tasked with a number of delicate diplomatic missions in the service of his master, whom he always served ‘summa cum laude’.Footnote 43 These brought him to Ferrara, Mantua, Florence and Rome, where he was received by popes Gregory xiii and Clement viii. His biographer, Jacob Zemann, described him as a ‘very cautious but at the same time very devout politician’.Footnote 44 It was in those years, spent in the library of his protector and in frequent travels, that Albizzi collected the rich heraldic and genealogical materials on European princely families that would allow him to publish his sumptuously decorated Principum christianorum stemmata, printed in Augsburg in 1600, and dedicated to Cardinal Andreas (in the year of his death). The publication was updated and reprinted several times, culminating in two 1627 editions, in German and Latin.

As much as Albizzi's faith was practised in private and circumspectly, and despite the protection he received thanks to his Habsburg master, Albizzi's religious identity must have been known to some. In fact, circumstances changed fairly swiftly for him in 1600 after the death of the cardinal: Andreas – then only aged forty-two – was at the time in Rome to attend the Jubilee, having surrendered the governership of the Low Countries to undertake the pilgrimage. In that same year, the Holy Office began an inquiry into Albizzi, forcing him to rush through the sale of his family properties in Tuscany, and to move to Augsburg, at the time a bi-confessional city.

In Augsburg Albizzi was part of the circle of Marcus Welser, an astronomer and correspondent of Galileo, a learned man and politician who later became a member of the Accademia dei Lincei.Footnote 45 He was also a relative of Cardinal Andreas's mother. To Welser – among other possible attributions – is often credited the authorship of the Squittinio della libertà veneta (1612) [The scrutiny of Venetian freedom], a key conservative pamphlet that opposed Venice's claims to political independence, and argued for its submission to imperial authority after the struggles of the Interdict crisis.Footnote 46 Pierre Gassendi, probably aware of Antonio's links with the Habsburgs, suggested that Albizzi himself might also have been a possible author of the booklet, an idea that should be discarded by scholars. Indeed, by 1612 Albizzi was most certainly removed from imperial politics, and had become a committed Lutheran: surely, he would have never suggested the imposition of a strong Catholic imperial hand on Venice?Footnote 47

In keeping with his political connections, Albizzi moved to Innsbruck; but when in 1606 Rudolf ii forbade Protestants to be in his service, he relocated to Kempten, a Lutheran town within the territories of the elector of Saxony, and therefore exempt from imperial and inquisitorial jurisdiction.

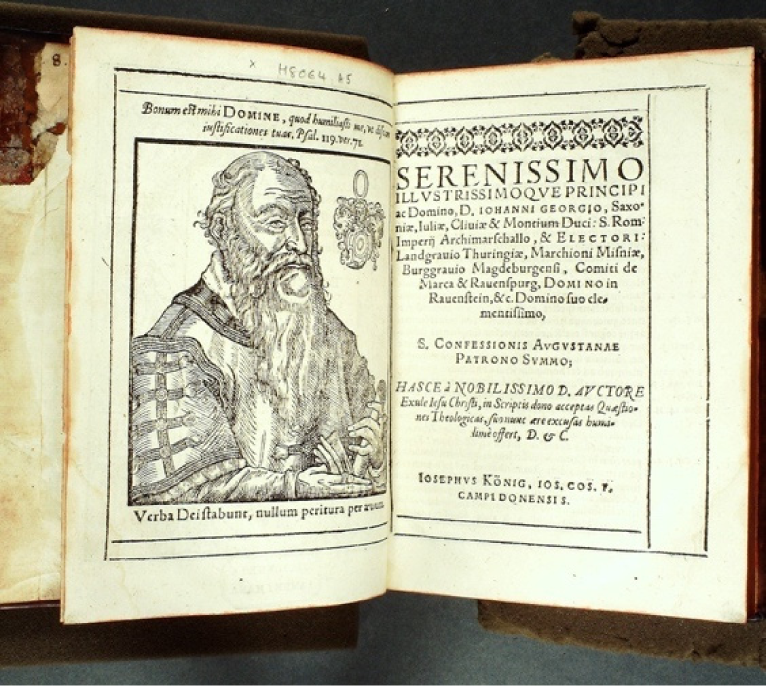

Albizzi's case had no little resonance in Italy; twice he was summoned by the Holy Office. Both the nuncio in Lucerne and Albizzi's family attempted to have him brought back to Italy in order to abjure his Lutheranism. On 4 June 1626 his second inquisitorial subpoena was nailed to the door of a monastery not far from Kempten, but by then Albizzi was already senile.Footnote 48 He died in 1627, leaving his patrimony and library to the town, his refuge, where he had passed twenty quiet years. There he enjoyed music, and gave afternoon concerts. Albizzi also offered his expertise to the town, advising its senate on political and legal matters; he was also a patron of the parish school, and a philanthropist: activities that kept him in high esteem. It is interesting to note that even today Albizzi is remembered in a modern fresco (see Figure 4), painted by a certain Franz Weiß (1903–82) on the external wall of a Kempten pharmacy. He is depicted with his Principum christianorum stemmata under his arm. It is an imaginary portrait that does not take into account the one that appears in the first volume of Albizzi's Exercitationes theologicae (see Figure 5), where he is portrayed with the respectable long beard of a seasoned imperial servant and elder of the Church.Footnote 49

Figure 4. Franz Weiß, Fresco of Antonio Albizzi, Kempten. Photograph © René & Peter van der Krogt and reproduced by kind permission.

Figure 5. Antonio Albizzi, Exercitationes theologicae, Kempten: Kraus 1616, Lambeth Palace Library, H8064.A51616TPv-f1. Reproduced by kind permission of Lambeth Palace Library.

The Exercitationes (see Figure 6) were published in two lengthy volumes by Albizzi in Kempten in 1616 and 1617 respectively, as a summa of Lutheran doctrine: his own image was flanked by reminders of the two key Protestant principles: sola fide and sola Scriptura.Footnote 50

Figure 6. Albizzi, Exercitationes theologicae.

The title page page of the Exercitationes shows the four evangelists at the corners, heaven and hell top and bottom, and a justified man opposite a sinner. Albizzi was introduced as ‘a heroic man of splendid virtue’. The book was dedicated to Duke Johann Georg i of Saxony, and was a catalogue of quaestiones on original sin, salvation, justification, free will, the role of Scripture, the doctrine of the Spirit and, most important, the role of civil and ecclesiastical authority. Given their length and density, the Exercitationes were most certainly not a work of propaganda. They were probably intended by Albizzi as a way of establishing himself as a theologian.Footnote 51

Conversely, Marcantonio De Dominis's Epistola in qua causas discessus a suo episcopatu exponit [Letter in which he explains the reasons of the renunciation to his episcopate] was surely intended as a propaganda tool.Footnote 52 Also printed in Kempten in 1617 by Christopher Kraus, it was one of many editions, common all over Europe at the time, but the role played in it by Antonio Albizzi can only be speculative. The Epistola was a sort of anti-Roman manifesto, written by the former Catholic bishop of Split (now in Croatia) who later became dean of Windsor and a courtier to James i, before he recanted and returned to Rome. The religious content of the Epistola, its anti-papalism, common connections in Istria and Dalmatia, and – most important – a shared belief in the primacy of civil authority over the ecclesiastical, make Albizzi's involvement in its printing credible rather than certain.

IV

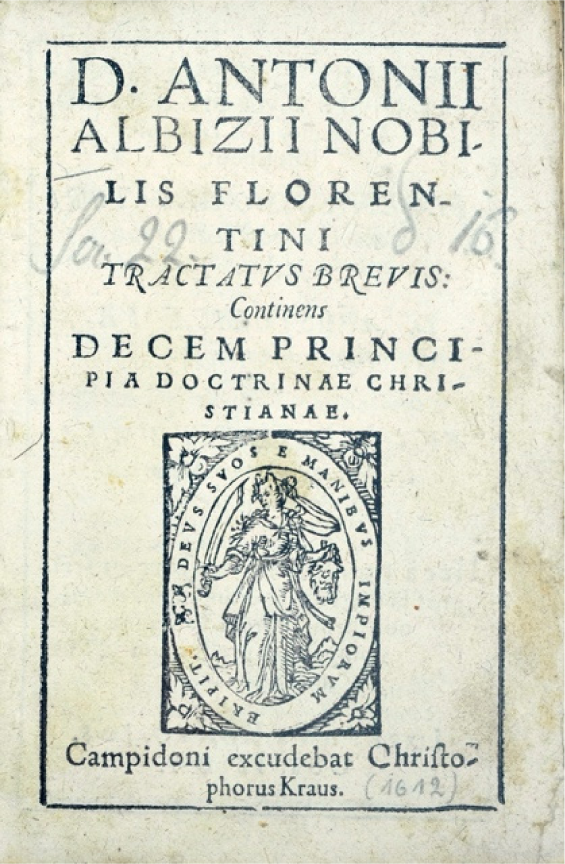

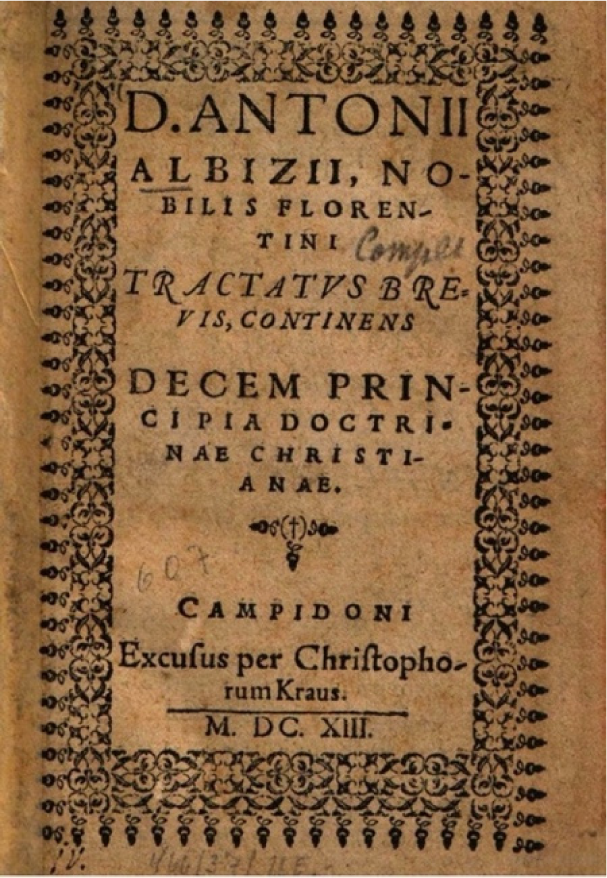

Most significantly, Antonio Albizzi was the author of the explicitly Lutheran Tractatus brevis continens decem principia doctrinae christianae, printed in Kempten, again by Christopher Kraus, in 1612. Kraus's anti-Catholic sentiments were hardly concealed, as can be seen from his emblem: an image of Judith holding in her hands the hair of the beheaded Holofernes, surrounded by the verse ‘Eripit Deus suos e manibus impiorum’ (‘God rescues his own from the hands of the ungodly’) (see Figure 7). It was probably the reprint of the Tractatus in 1613 (with a new frontispiece) that had worried Cardinal Millini (see Figure 8). Nevertheless, there is not much evidence of its spread in Italy, albeit the decision to print it in Latin inevitably limited its ambitions. The text followed the classic scheme of loci communes, listing the fundamental doctrines of the Church followed by scriptural evidence. According to Albizzi, the only purpose of Scriptures was to show how faith in the sacrifice of the cross alone is the road to salvation: the booklet is very much focused on the ‘benefit of Christ’, and on Jesus’ salvific atonement.

Figure 7. Antonio Albizzi, Tractatus brevis continens decem principia doctrinae christianae, 1612. Reproduced by kind permission of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze.

Figure 8. Antonio Albizzi, Tractatus brevis 1613. Internet Commons.

In Albizzi's prose it is almost possible to detect evidence of early Lutheranism, echoes of Luther's early writings: a sort of nostalgic religion, far indeed from the harsh debates between Philippists and Gnesio-Lutherans that had split the Augsburg Confession. The Tractatus was the work of an isolated man, confined to a small provincial town, working on the margins of the theological debates of his times: it was full of the moderate tones, the spiritual commitment and the enthusiasm of early sixteenth-century piety.

The Tractatus opens with a dedication to Martin Aichmann, sometime right-hand man to the duke of Wüttemberg in Tübingen who in 1601 had become the secret counsellor to the elector of Saxony until his death in 1616 in Dresden. Aichmann was described as a strenuous upholder of apostolic truth, and as a pious philanthropist who had worked to enhance popular literacy and knowledge of the Gospel. The author of the dedicatory letter of the Tractatus was Joseph König, Kempten's ‘scholarca and bibliotecarius meritissimus’ (at least according to Zemann, the Lutheran pastor of Kempten who would later record Albizzi's biography). König would also serve as the town mayor between 1592 and 1600. One of Albizzi's closest friends, König was clearly appreciated by the locals, as his coat of arms is one of the two held by a statue of a Roman general that, standing on top of a column, to this day oversees Kempten's Rathaus.

It is also worth observing that the Tractatus twice includes the identical grotesque mask of the Lettera di N. ad un amico, proving once again the publication of the Letter by Christopher Kraus in Kempten, and making Albizzi almost certainly its author (see Figure 9 and 10).

Figure 9. Lettera di N. ad un amico, detail

Figure 10. Albizzi, Tractatus brevis, 1613. Internet Commons.

Albizzi's authorship was a fact possibly even known to Cardinal Millini, who, despite his concerns, failed to notify the Congregation of the Index of Prohibited Books of the existence of both pamphlets. Was this a way to avoid irritating those close to the Habsburgs (after all, Albizzi had been a family confidant for a long time)? According to Decio Memmoli, Millini's secretary and biographer, ‘the Cardinal always acted in his affairs with two purposes in mind: one to preserve and defend papal dignity and aims, the other to avoid any breakdown in relations with the princes’.Footnote 53

In its brevity and simplicity, and like the Tractatus, the Letter was also an echo of the beginnings of the Reformation, avoiding any temptation to enter in the storms of theological controversies so typical of the age. Its text insisted exclusively on the contraposition between the Christ of the Scriptures and the pope in Rome, using various bible quotations to show the contrast between Catholicism and the true apostolic Church, and to illustrate the apostasy of popery. Sentences like ‘The true Church was the apostolic one, and well before anybody ever heard of the papacy’ and ‘He who leaves the Roman Church … trusts not his intellect, but the word of God’ were effective and direct. This was a simple, clear, argument, that did not lose itself in quarrels which would have been difficult for most readers to understand.

The Letter was centred on the core of the conflict that divided Christians: the schism between true and false faith, gospel preaching and papal authority, Christ and AntiChrist. In this sense – more than the Latin Tractatus – the Letter's style was very effective. It was a simple re-presentation of a trope of the early Reformation, one that had been a key part of the visual identity of Lutheranism, and that had produced some of its most famous images. It is enough to think of Lucas Cranach the Younger's Principal differences between the true religion of Christ and the false, idolatrous religion of the AntiChrist (c.1545) (see Figure 11). This provides a visual comparison of Lutheranism and Catholicism, encapsulating the doctrinal conflicts between Protestantism and the Church of Rome. To the left, in front of a congregation in which some German princes can be recognised, Luther preaches his theology of the cross; underneath, the sacraments of baptism and eucharist are administered. To the right, a portly Franciscan preaches to a crowd of priests, monks and soldiers, inspired by the devil sitting on his shoulder. The corruption of the Church of Rome is evident from the coins dropping out of the pockets of a friar, whilst on the floor lie bags and coffers full of money. The pope, sitting to the right at a table with the tiara, spends his time accruing wealth, thanks to the sale of indulgences and ecclesiastical benefices. In the background, a series of superstitious rites are practised: mass, the anointing of the sick, the blessing of bells. From above, God and even St Francis himself are witnessing the scene angrily, sending down lightning and thunderclaps onto this fake Church.

Figure 11. Lucas Cranach the Younger, Principal differences between the true religion of Christ and the false, idolatrous religion of the AntiChrist, Photo © Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Kupferstichkabinett, SMB/Jörg P. Anders.

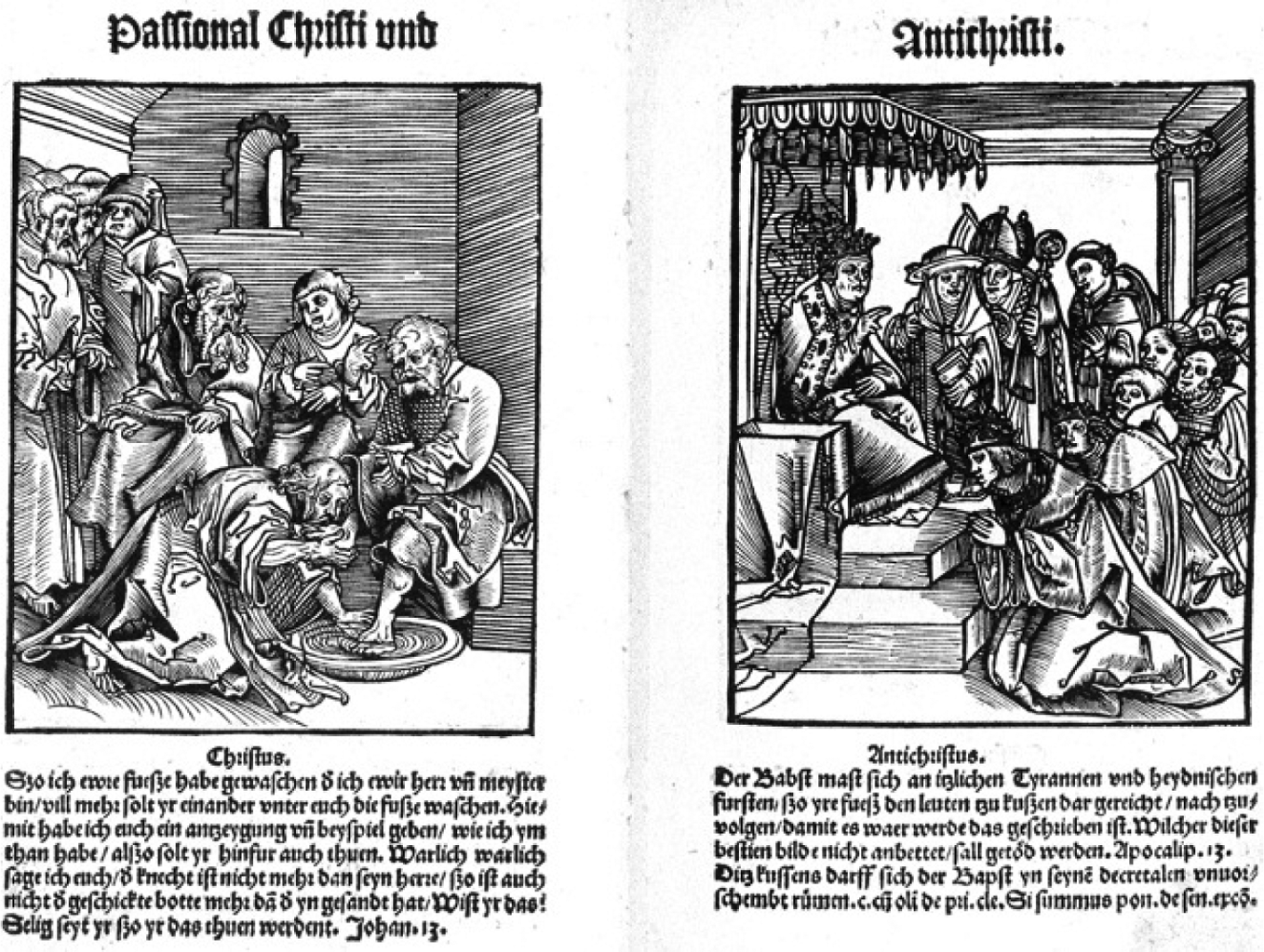

Similar in content was the Passional Christi und Antichristi printed by Luther and Melanchthon in 1521. This was a short commentary on images by Lucas Cranach the Elder that juxtaposed and contrasted the figures of Christ and of the pope-AntiChrist. One, for example, compared Jesus kicking the merchants out of the temple with the pope selling indulgences. Another (see Figure 12) shows Christ washing the feet of his disciples while the pope commands rulers to kneel at his feet.Footnote 54

Figure 12. Lucas Cranach th Elder, Passional Christi und Antichristi, 1521. Wikimedia Commons

A century after these images, the text of the Letter was repeating the same tropes. Was this, perhaps inadvertently, a call to go back to the enthusiasms of the first years of the Reformation? Was it an invitation to restart from the day when, in Worms, Luther proclaimed in front of Charles v and Cardinal Aleandro that his conscience was prisoner only to the Word of God? Nobody, back then, would have imagined it possible that only thirty years later someone would have written that ‘not only in Italy is Satan, not only in Italy is the Antichrist’, arguing that the authoritarianism of the papacy was now well spread also among Protestants.Footnote 55 ‘Christ versus AntiChrist’ was a rhetorical trope destined for the longue durée, even without the involvement of images: it was even included in the Antitheses Pseudochristi, edited by Giorgio Biandrata and Ferenc Dávid in Alba Iulia (Transylvania) in 1568 as part of the anthology De vera et falsa unius Dei patris, filii, et spiritus sancti cognitione, that would later become a true pillar of Unitarian antiTrinitarism.

V

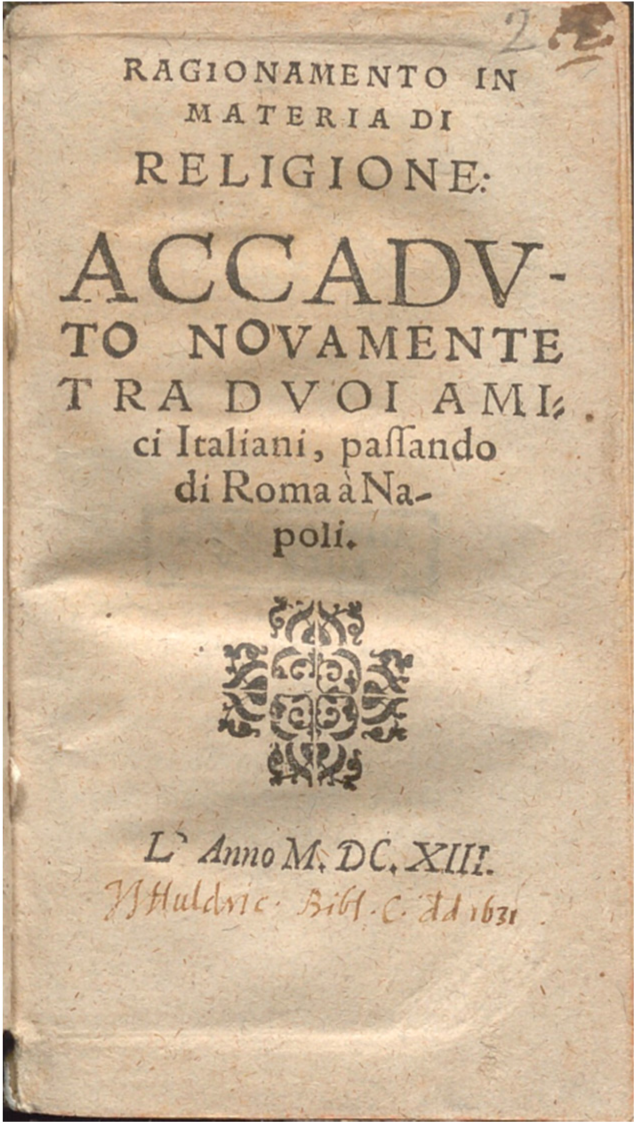

Without any doubt, it is a similar simplified theology that characterises the Ragionamento in materia di religione accaduto novamente tra due amici italiani passando da Roma a Napoli l'anno 1613. This pamphlet, which also alarmed Cardinal Millini, is centred once again on justification by faith alone, and on the ‘benefit of Christ’. This can now confidently be attributed to Antonio Albizzi.

The Ragionamento is a small booklet in octavo, without date or place of publication, but can be ascribed to Christopher Kraus in Kempten as publisher as the ornaments in its frontispiece (see Figures 13 and 14) are the same as those used by Kraus in the decorative strips subdividing the chapters of the Tractatus brevis (see Figure 15).

Figure 13. Ragionamento in materia di religione accaduto novamente tra due amici italiani passando da Roma a Napoli l'anno 1613. Reproduced by kind permission of the Zentralbibliothek Zürich.

Figure 14. Ragionamento, detail.

Figure 15. Albizzi, Tractatus brevis, detail.

The Ragionamento is also an extremely rare text; only three copies are known today. The first, preserved at the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, is so damaged that no access to it (physical or via reproduction) is currently given to scholars. The second, held at Zürich's Zentralbibliothek, is missing the last 24 of its 48 pages. The third, despite being in the catalogue of the Württembergische Landesbibliothek, appears to have been lost by the library. Analysis, therefore, can only be based on the partial Zürich copy.

The text is structured as a dialogue between Pistophilo (lover of the faith) and Erasto, whose name nevertheless appears in full only once, at the start, to be then always abbreviated as ‘Erg.’. This poses some problems: it is in fact impossible to identify Erasto with Basel's theologian and doctor Thomas Erastus (1524–83), author of a famous treatise (published in England by Giacomo Castelvetro in 1589) that denied the validity of ecclesiastical excommunications and argued for the primacy of state power over the Church. The hypothesis of a typo in the first line (a sort of involuntary hypercorrection by Kraus) seems credible; we would argue that it is correct to call our imaginary character Ergasto, as the abbreviation actually suggests (this is also what he is called in the fifth page of the Ragionamento). A militant Catholic character, the name Ergasto was probably taken by Albizzi from a certain Ergastus, the protagonist of a 1587 eponymous drama written by the learned Jesuit and classicist Francesco Benci, a professor at the Roman College who used to compose pious plays for the graduation of his students.Footnote 56 There is further proof of this hypothesis in the fact that another of Benci's dramas, published in Rome in 1590, was called Philotimus, a name that might well have suggested Pistophilo to Albizzi.

It is not necessary to devote much time to the actual content of the Ragionamento, a didactic script and a sort of catechism in all but name. Despite the title, no mention of Naples is made in the part of the text available to us. The text is structured as a dialogue between the defence of the authority of the Bible by Pistophilo, a position supported by a huge number of biblical quotations, and Ergastus' apologia for ‘what the holy Catholic Church believes, might it be in the Bible or not’.Footnote 57 For Ergastus, the Church corresponds to pope and priests, whose purpose is to teach all Christian people. This would exclude ‘the people and the magistrate, that are respectively more numerous and the most important part of it’, Pistophilo promptly objects.Footnote 58 Pistophilo's argument is rather erastian, that ‘the Church's ministers … are therefore servants of the common good, and chiefly of the magistrate’.Footnote 59 To Pistophilo, papal authority has no foundation in the Bible, that instead is ‘the only rule and norm of faith and of Christian worship’.Footnote 60 In case of doctrinal disagreements, patient examination of Scripture alone, according to Pistophilo, can resolve any controversy. This was the rather hopeful and naïve certainty that Albizzi clearly still held to, despite the conflicts that were dividing Lutheranism at the time.

How the argument between Ergasto and Pistophilo continues in the remaining pages of the Ragionamento is not known, but it presumably includes a discussion of justification by faith alone. It is not possible to hazard any further assumptions about this short and unoriginal Lutheran pamphlet, that nevertheless was considered worthy of the attention of the secretary of the Holy Office in 1613.

VI

This article has shed some light on a previously neglected series of Lutheran publications in Italian that appeared in the 1610s, clarifying their provenance, and identifying in the curious figure of the Florentine exile Antonio Albizzi their main author. It seems impossible to illuminate further Albizzi's networks in Germany, Italy and, crucially, in Slovenia, a place that has surprisingly proved to be a key, albeit largely ignored, connection. Research in the archives of Florence, Rome, Vienna, Ljubljana and Kempten has brought no further result. Unresolved also is the identity of the promoter of 1609 edition of the Catechismo piocciolo, as any involvement by Antonio Albizzi appears improbable (he would have at least corrected its title).

There are two sets of conclusions that can nevertheless be drawn from these materials: the first concerns the aims and ambitions of Antonio Albizzi himself; the second addresses the place of these Lutheran works in the larger picture of Protestant propaganda in Counter-Reformation Italy.

Albizzi's commitment to Lutheran propaganda directed to Italy in the 1610s remains puzzling. A country, Italy, whose unsuccessful Reformation had been inspired more by Swiss Calvinism (thanks to many urban, mercantile and financial links) than German Lutheranism, could hardly be thought likely to be receptive to this message. With a pope-inquisitor like Paul v in Rome, with a country fully under the grip of the Counter-Reformation and with the last fires of hope brought by the Venetian Interdict now expired, what might have been the reason behind Albizzi's moderate Lutheran publications? Who might have been the interlocutors of these pamphlets, sent by an old Florentine patrician from his small provincial refuge? At this time most had probably forgotten the philo-Lutheranism of the emperor Maximilian ii, and the humanistic syncretism of Rudolf ii's Prague, two projects to which Albizzi had probably subscribed in his youth. We do not have any evidence that would offer us an answer. We can only register the personal and political isolation of Antonio Albizzi in his later life, the result of his strong religious convictions, one that would take him far away from the wealthy, peaceful and bigoted Florence of the seventeenth-century Medicis. Albizzi made a coherent Lutheran choice, both in its political implications (he was after all a strong believer in the subordination of the Church to the State), and for its staunch belief in salvation by faith alone. This was an article full of doctrinal and social consequences, whose complexity had divided subscribers to the Augsburg confession – thus Philippists and Gnesio-Lutherans: theological debates of which there is no echo in Albizzi's works. With his moderation, he seemed not to realise that the days of the early Reformation had long gone, and that far from an expansion of Lutheranism, what was on the cards was a powerful Catholic reaction, one that – on the eve of the Thirty Years’ War – can also explain the spreading in the Habsburg lands of an esoteric Rosicrucian utopia.Footnote 61 Albizzi was keen to testify to the core beliefs of early Lutheranism, to Luther's interpretation of St Paul's writings and to his call to sola fides and sola Scriptura. It was a commitment, in certain respects, far from the reality of his age. In 1627, the year of his death, the armies of Tilly and Wallenstein had conquered Silesia, Schleswig-Holstein and Jutland for Austria and the Catholic faith, and were ready to flood much of the Baltic coast, posing a dreadful menace to the Lutheran cause itself.

All this notwithstanding, Albizzi's case actually complicates our knowledge of Italian seventeenth-century Protestant propaganda, adding a previously unknown Lutheran component, no matter how small and individual this was. Scholars of our subject might have to accept that, for a variety of reasons – from the paucity of the materials to the ‘success’ of repression – the puzzle lacks many pieces. Sources are often thin, and limited in their numbers. Of course Albizzi's initiative, despite being that of a very learned man, and indeed a former politician, was rather Quixotic in its ambition. In some way, it was a throw-back to an earlier age. But nevertheless these writings worried the Inquisition in Rome, and might have been able to circulate the peninsula, side by side with Calvinist devotional materials. Clearly, some dissenting conventicles were still in existence. But, we have to be clear on their limits. After the solution to the Interdict crisis, the Reformation had ceased to offer Italians a real political alternative to the rampant throne and altar alliance of the Counter-Reformation. Of course, for a variety of individual reasons, Protestants – and Albizzi was one of them – kept dreaming of converting the land of the pope; but their numbers were diminishing, and they would almost completely disappear by the end of the iron century, not to resurface for a long while. Protestantism was starting to lose its political appeal too, and Protestant texts – as has been already demonstratedFootnote 62 – were feeding other kinds of dissent, more often aligned with individual libertinism than a clear Calvinist or Lutheran identity. With his Lutheranism, Albizzi represents an eccentric case, but in this larger context there is no divergence between his works and the Reformed pamphlets circulating in Italy: by that time it was too late for them to have any real effect. Indeed, the Holy Office was well aware of this: during the Thirty Years War, and in general in the 1610s, the increasing control exercised over foreign publications and Protestant texts helped feed the rhetoric of confessional conflict and fear of the enemy. Not even in Rome did anyone believe that in their generation the Reformation could take hold in Italy: that threat, no matter how serious it had been in Venice at the start of the decade, had been seen off much earlier, in the mid-sixteenth century. In some ways, Millini and Albizzi, first and foremost two highly capable politicians, are like two mirrors, reflecting into each other their individual quests for legitimation. For Millini, fretting about Protestant pamphlets was a way to justify the omnipresent actions of the Holy Office, and its reach within, as much as without, the Catholic Church. For Albizzi, writing theological pamphlets, and proclaiming the Gospel that he had discovered, was perhaps a way – after all those years of nicodemism – to justify his life in exile, and to be accepted in the small community of Kempten, at least as much as to convert his fellow Italians.

APPENDIX I

[Ar] Lettera di N. ad Uno Amico, nella quale Brevemente Racconta le Cause perch'egli sia Partito dalla Religione Romana

A quanto tu mi scrivi che fuori dalla Chiesa di Dio non possa alcun huomo salvarsi, respondo che ciò è vero, sì come è certo ancora che tutti quelli ch'al tempo del diluvio furono fuor dell'arca perirono. Ma io ti prego che vogli considerare ancora che coloro che credono et confessano gli articoli della fede tutti, che son compresi nel simbolo degl'apostoli, et quanto si contiene nelle sacre Scritture canoniche non sono né possono esser fuor della vera Chiesa, peroché non è dubbio che fra gl'apostoli fu già la vera Chiesa christiana, avanti che si sapesse cosa alcuna della dignità et primato del papa. Nella qual Chiesa non si celebrava, la messa ma la cena, et si porgeva a ciaschuno egualmente il pane e il vino secondo il precetto di Christo. Né era allora o frate o prete che sacrificasse, né vergine Maria o alcun santo già morto si invocava; ai vescovi et ministri della Chiesa non era proibito il matrimonio, et molte cose sì fatte non erano che hoggi sono in uso nella Chiesa romana. Se adunque hoggi si trova Chiesa che insegna e fa le stesse cose a punto che quella degl'apostoli, perché non si dee dire che una tal Chiesa sia così ben vera Chiesa christiana come fu quella degl'apostoli? Et come è mai possibile dire con verità che chi serva et ritiene nel culto di Dio la stessa maniera a punto che tennero gl'apostoli si parta dalla vera Chiesa? Anzi! Né parte ancora dalla Chiesa romana (com'ella fu al tempo degl'apostoli et di san Paulo) colui che serva la dottrina, massimamente della iustificatione, la qual san Paulo insegna a quella Chiesa nella sua epistola.

Che [Av] alcuno poi si parta dalla Chiesa romana nel modo ch'ella è hora et da un tempo in qua la causa è questa: che ciaschedun christiano nel battesmo giura l'obedienza et fedeltà a Christo, e a Satana renuncia et alle opere sue. Però non può un tale, se non si ribella a Christo et perde la salute eterna acquistatali da lui, lasciar il pacto et l'obligo che ha contracto con Christo, non essendo possibile, sì come Christo dice,Footnote 1 servire a duoi signori che comandano cose contrarie, sì come è il papa et Christo. Ché se Christo comanda che pigliamo la cena sua nel modo ch'egli ha ordinato, e il papa vuole che si pigli altramente, non se li può obedire. Se Christo vuole, secondo la legge, che Dio solo s'adori et a lui solo spiritualmente si serva,Footnote 2 non si può far quel che comanda il papa, cioè che un tal honore si dia ancora ad altri. Se Christo dice di esser lui la via, la verità et la vita, et che nessuno può pervenire al regno del Padre suo se non mediante lui,Footnote 3 non bisogna cercar di pervenirvi (sì come vuol il papa) per mezzo di Maria vergine over dei santi o delle opere proprie. Se Christo, conforme a Esaia propheta, ci insegna [che] nel culto divino non vale et non ha luogo comandamento humano,Footnote 4 non si deve obedire ai comandamenti del papa, che humani sono, in cose di religione et di fede. Né si può reputare per vera Chiesa quella che nella parola et precetti di Christo non resta et la voce di lui non ascolta et non segue, ma quella d'altri,Footnote 5 peroché una tal Chiesa, se ben fu per avanti la sposa di Christo, nondimeno è diventata poi meretrice,Footnote 6 come intervenne ancora alla sinagoga iudaica. Et però in tal caso, quando la madre parte dal marito et si coniunge con altri, non sono più obligati li figliuoli a seguirla o obedirla, ma solo il padre, massimamente havendo noi espresso comandamento: «Udite lui»,Footnote 7 et dicendo Christo:Footnote 8 «Chi ama altri più che me [A2r] non è degno di me».

Né è per questo che chi perciò si parte dalla Chiesa romana o dalli suoi presuma di sé stesso o si confidi nel proprio intellet[t]o; anzi, confida in Dio et nella sua parola, et in Christo et nei propheti et app[o]stoli confida come sopra un fondamento stabileFootnote 9 et sopra muri fortissimi,Footnote 10 sopra dei quali è fabricata la vera Chiesa,Footnote 11 e abbraccia quella dottrina che, come dice san Paulo,Footnote 12 rende l'huomo perfetto e atto a ogni buona opera. Et veramente se siamo tenuti, secondo che dice san Pietro,Footnote 13 a render conto della nostra fede, come potremo noi rispondere a un che ci domandi perché noi obediamo al papa «più che a Christo, ch’è il vostro giudice et redemtore?». Perché laFootnote 14 risposta d'alcuni – Christo ci ha comandato di ascoltar la ChiesaFootnote 15 – non fa a proposito et non ci scusa, non parlando quivi Christo di papa over di cardinali o d'altri che dicano d'esser la Chiesa catholica et in verità non sono, ma della vera Chiesa, la quale s'ha da cognoscere per le Scritture sacre, et delle ingiurie poi et discordie che nascono fra i membri della dottrina. Peroché se ciò valesse potrebbono ancho scusarsi li giudei inverso Dio con dire:Footnote 16 «Non ci hai tu comandato di obedire al sommo sacerdote, et chi non lo obedisce sia castigato»? Certo meglio di noi, che un tal comandamento di obedir al papa non habbiamo. Ma il fatto è che neanche i giudei hebbero comandamento di obedir al pontifice o ad alcun altro in quelle cose che non fusser conformi alla legge di Dio et alla sua parola. Perciò per questa via non si può alcun scusare, ma è forza che insieme con la sua cieca guida caschino nella fossaFootnote 17 et perisca il seducto insieme con il seductoreFootnote 18 perché, come dice san Paulo,Footnote 19 ogni uno ha da portar [da sé] stesso il carico et ha da render conto dei fatti proprii.Footnote 20

Consideriamo adunque che Christo ci ha avertiti; però non potremo scusarci quando dica:Footnote 21 «Non t'ho [A2v] io ammonito e avisato che tu debba guardarti dalli falsi propheti, né ti lasci sedurre? Non t'ho io detto che surgeran fra voi falsi Christi et propheti, et faran miracoli falsi et apparenti per ingannarvi?.Footnote 22 Non vogliate lor credere né seguirli: io ve lo aviso per tempo, avanti che ciò intervenga. Non vi ho io detto ancora che regnerà il figliolo della damnatione et lo Antichristo?.Footnote 23 Perché non avete posto mente a tal cose e tutto esaminato secondo le Scritture?». Siamo pertanto in cosa di sì grande importanza com’è la eterna salute svegliatiFootnote 24 et diligenti non pigri o negligenti, et consideriamo che, mentre noi restiamo nella paterna religione senza cercar più oltre, venghiamo ad approvare et reputar per buono il fatto delli giudei et delli turchi i quali fanno il medesmo et stimano esser vero ciò che i ministri della lor Chiesa comandano, senza alcuno altro esamine, con tutto che Dio comandi:Footnote 25 «Non vogliate seguire i precetti dei padri vostri, perch'io sono il vostro Signore, ma seguitate solamente i miei».

[ [Ar] Letter from X. to a friend in which he briefly explains why he has left the Roman religion

About what you are writing me, that outside of the Church of God no man can save himself, I answer that this is true, as it is also sure that at the time of the deluge all those who were outside of the ark died. But I pray you that you would also consider that all those who believe and confess every article of the faith (as included in the Apostles’ creed, and in what is contained in the holy canonical Scriptures) cannot be outside of the true Church. There is in fact no doubt that among the Apostles was already the true Christian Church, well before anybody knew of the dignity and of the primacy of the Pope. In that Church, not the Mass, but the Supper was celebrated, and to everyone was equally offered bread and wine, according to Christ's teaching. There was then no friar or priest to make sacrifices; and nobody used to call upon the Virgin Mary, or a saint already dead. Marriage was not forbidden to bishops and ministers of the Church, and many other things were done that today are not practice in the Church. Therefore, if today we can find a Church that teaches and does the same things as the Apostles’ Church did, why should we not say that such a Church is as truly a Christian Church as that of the Apostles? How is it possible to say truthfully that those who worship and preserve in God's service the same customs of the Apostles have departed from the true Church? On the contrary! Nor departs from the Roman Church (as it was at the times of the Apostles and of St Paul) he who keeps the doctrine, and most chiefly that of justification, that St Paul taught to that church in his epistle.

This [Av] is the reason someone would leave the Roman Church as it is in its current condition (and it is such since a while): every Christian, in Baptism, takes an oath of obedience and faithfulness to Christ, and renounces Satan and his works. Therefore, one cannot – unless he rebels against Christ and loses the eternal salvation he has gained from him – leave the covenant and the obligation he has with Christ, as it is not possible, as Christ says,Footnote 26 to serve two masters who command opposite things, such as the Pope and Christ are. As if Christ commands that we take his Supper in the way he established, and the Pope wants us to take it in another way, we cannot obey both. If, according to the law, Christ wills that only God is to be worshipped and only he is to be spiritually served,Footnote 27 we cannot do as the Pope wishes, such as that we give this honour also to others. If Christ says that he only is the way, the truth, and the life, and that nobody can come into the kingdom of his Father if not by him,Footnote 28 we should not try to get in it (as the Pope wishes) thanks to the Virgin Mary, or the saints, or our works. If Christ, following the prophet Isaiah, teaches us that in divine worship no human commandment is valid or can take place,Footnote 29 we cannot obey the Pope's orders, which are human, in matters of religion and faith. Nor we can consider as true the Church that does not rest in the word and in the precepts of Christ, and that does not listen to and follow his voice, but to that of others.Footnote 30 Such a Church, even if it used to be the bride of Christ, is nevertheless now a prostitute,Footnote 31 as has happened to the Jewish synagogue. But in this case, when the mother leaves the husband and lies with others, her children are not anymore obliged to follow or obey her, but only the father. Most importantly, we have lived the commandment: ‘Listen to him’,Footnote 32 as Christ said:Footnote 33 ‘He who loves others more than me, [A2r] is not worthy of me’.

Therefore, it is not that he who leaves the Roman Church and his own is presumptuous, or too confident in his own intellect. On the contrary, he trusts in God and in his word, and he trusts in Christ, and in the Prophets, and in the Apostles, as on firm foundationsFootnote 34 and strong wallsFootnote 35 upon which the true Church is built.Footnote 36 Further, he embraces that doctrine that, as Paul says,Footnote 37 makes man perfect and ready for any good work. And, really, if we are expected, as St Peter says,Footnote 38 to give testimony to our faith, how can we be witnesses before someone who might ask why we obey the Pope ‘more than Christ who is your judge and redeemer?’. In fact, the answer that some give – that Christ has ordered us to listen to the ChurchFootnote 39 – is not fitting, and it does not excuse us, as Christ was not speaking here of the Pope, or of the Cardinals, or of others who claim to be the Catholic Church but who actually are not, but of the true Church, that one we can know via the holy Scriptures, and for the injuries it receives, and of the disagreement emerging among the members of the [same] doctrine. Indeed, if this argument is valid, even the Jews could excuse themselves with God, saying:Footnote 40 ‘Have you not told us to obey the High Priest, and that those who do not obey him should be punished?’ They would argue this even more strongly than us, as we do not have such commandment to obey the Pope. But the fact is that not even the Jews had as commandment to obey the pontifex or any other in those matters that did not conform to the laws of God and to his word. Therefore, nobody can be excused of it in this manner, as it is inevitable that with the Pope's blind leadership they will fall in the pit,Footnote 41 where the seduced and the seducer will perish together;Footnote 42 as St Paul says,Footnote 43 everyone has to carry for himself his burden, and to be accountable for his own doings.Footnote 44

Let us then ponder that Christ has warned us; so we will not be able to be excused when he will say:Footnote 45 ‘Have I not [A2v] admonished you, and alerted you, to watch yourself from the false prophets, and to not let yourself be seduced? Have I not told you that false Christs and prophets will come among you, and will make false and visible miracles to trick you?Footnote 46 Do not believe them, nor follow them: I am telling you this well ahead of time, before this will happen. Have I not told you that the son of perdition will reign, and the Anti-Christ?Footnote 47 Why have you not paid attention to these things, and examined everything according to Scripture?’ Let us therefore be awakenedFootnote 48 on matters of such importance like our eternal salvation, and be diligent in them, and not be lazy or negligent. Let us consider that as we remain in the religion of our fathers without enquiring any further, we end up approving of the fact that Jews and Turks behave similarly, as they consider to be true what the ministers of their church ordain, without any further examination, despite God ordering:Footnote 49 ‘Do not follow the precepts of your fathers, as I am your Lord, and follow only mine’.]