In Chapters 3, 4, and 5, I traced the conveyance and construction of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities through both jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities in Indonesia and Tanzania. Although I did not select these two countries on the basis of variations in initial conditions or eventual outcomes relevant to the implementation of REDD+ or the recognition and protection of rights, a number of lessons can nonetheless be drawn from a comparison of experiences across sites and levels of law in these two countries. In what follows, I discuss findings that relate to rights in the context of the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities at the national level, before turning to the development and implementation of project-based REDD+ activities at the local level. I conclude with a global comparison of the intersections between rights and various REDD+ activities in these two countries.

6.1 Rights and Jurisdictional REDD+ in Indonesia and Tanzania

At the national level, the conveyance and construction of rights in Indonesia and Tanzania followed a roughly similar trajectory in that references to human rights obligations, principles, and issues gradually increased throughout the development of a national strategy or the formulation of a set of social and environmental safeguards for REDD+. In addition, in both countries, the initial conveyance of legal norms triggered a process of construction that generated new hybrid legal norms.Footnote 932 This suggests that the domestic implementation of REDD+ has the potential to provide opportunities for the promotion of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in developing countries. These two case studies reveal that jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts may trigger at least one pathway for the conveyance and construction of Indigenous and community rights in developing countries.

My analysis of the experience in Indonesia suggests that international funding for jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities provided by Norway and its associated conditions led Indonesian government officials to adopt legal norms relating to the full and effective participation of stakeholders (specifically including “Indigenous Peoples”) in the design and implementation of REDD+. Because the material benefits of obtaining funding exceeded the political costs of facilitating the participation of stakeholders, the Indonesian government eventually held a series of multi-stakeholder consultations on the development of a national REDD+ strategy at the national and regional levels. In turn, the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities created new and unique opportunities for Indonesian NGOs to pressure Indonesian government officials to recognize and protect their rights. This mobilization played a key role in triggering the conveyance of rights to Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ readiness efforts. Finally, I argued that by engaging in a process of persuasive argumentation with their domestic and international interlocutors throughout the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities, Indonesian officials in the National REDD+ Taskforce and Agency developed and internalized new norms about the appropriateness of respecting the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in the context of REDD+. The ultimate outcome of this deliberative process was the construction of a new hybrid legal norm extending rights formally held by Indigenous Peoples under international law to both Indigenous Peoples (conceived of as masyarakat adat – the preferred term of Indigenous activists in Indonesia) and non-Indigenous local communities.Footnote 933

The causal pathway that helps explain the conveyance and construction of rights in the context of the development of Tanzania’s policy on social and environmental safeguards is broadly similar to the one I have just described. To begin with, the National REDD+ Taskforce’s commitment to developing a policy on social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ was driven by the combined effect of the mechanisms of cost-benefit adoption and mobilization. Indeed, Tanzanian officials committed to developing a set of social and environmental safeguards for REDD+ because this would enable them to eventually access sources of finance for REDD+ as well as respond to one of the main demands expressed by domestic NGOs. Moreover, the use of the REDD+ SES Initiative in the development of a policy on social and environmental safeguards fostered the engagement of Tanzanian government officials in a deliberative discourse with other domestic actors and their international interlocutors around the nature and extent of participatory rights in the context of REDD+. This process of persuasive argumentation explained how exogenous legal norms relating to the rights of Indigenous Peoples were eventually translated into new hybrid legal norms benefiting forest-dependent communities and marginalized communities, but not Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 934

One notable difference between these two cases concerns the way in which the policies for jurisdictional REDD+ address the distinctive status and rights of Indigenous Peoples. It is important to recall that the traditional position of both the Indonesian and Tanzanian governments has been to deny the existence of Indigenous Peoples on their territories.Footnote 935 Tanzania’s national REDD+ strategy and safeguards do not recognize that the concept of Indigenous Peoples is applicable in its territory and extend Indigenous rights to forest-dependent communities but not to Indigenous Peoples as such. Instead, the development of land and resource rights in Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy built on existing endogenous legal norms regarding the legitimacy of village governance and the superiority of participatory forest management that excluded Indigenous communities from their purview. What is more, by identifying pastoralism as a driver of deforestation, the strategy envisages policy interventions that may ultimately have negative implications for the rights of Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 936 Conversely, Indonesia’s national REDD+ strategy and safeguards incorporate numerous references to the status and rights of Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 937 – so much so that Indigenous activists in Indonesia have called on the Indonesian government to implement the national REDD+ strategy and have relied on it in their broader advocacy efforts.Footnote 938

I would offer two possible, complementary explanations for these differing outcomes. In line with existing research on transnational processes of persuasive argumentation,Footnote 939 the experience of Tanzania may simply reveal the enduring resilience of a powerful counter-norm to the effect that all Tanzanians are Indigenous and that the concept of Indigenous Peoples is a concept that applies to pre-colonial communities in the Americas. In the case of the National REDD+ Strategy, this counter-norm prevented the internalization of any exogenous norms relating to the concept and rights of Indigenous Peoples. In the case of the safeguards policy, this counter-norm led to the construction of a hybrid legal norm providing Indigenous rights to forest-dependent communities only. By contrast, Indigenous activists in Indonesia were capable of enhancing the resonance of exogenous Indigenous rights norms because they were able to align them with existing endogenous norms relating to the status and rights of masyarakat adat communities in Indonesia – a tactic that other scholars have uncovered in their work on the translation or vernacularization of international norms.Footnote 940

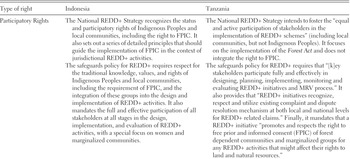

Table 6.1 Overview of the treatment of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities in the jurisdictional REDD+ policies adopted in Indonesia and Tanzania

In addition, this variation may also be the product of key differences in the resources and opportunities open to Indigenous activists in both countries and may thus speak to the scope conditions for the effectiveness of mobilization as a causal mechanism for the conveyance of legal norms.Footnote 941 In accordance with resource mobilization theory, the relative success of Indigenous activists in Indonesia might be explained by their greater access to financial resources, their superior level of organization, their connections with international NGOs and networks, and their ability to build alliances with other domestic environmental and human rights NGOs.Footnote 942 In comparison, the Indigenous movement in Tanzania is disjointed and fragmented and did not build effective alliances with other domestic or international actors both in generalFootnote 943 and in the particular context of Tanzania’s REDD+ readiness process.Footnote 944 In addition, a comparison of the political opportunity structure of the jurisdictional REDD+ readiness process in both countries suggests that Indonesia likely provided greater opportunities for domestic mobilization than Tanzania. Indonesian NGOs were able to take advantage of the openings provided by the consultative and inclusive manner in which the REDD+ strategy and safeguards were developed, the reformist officials and experts that were appointed to the National REDD+ Taskforce, and the relative marginalization of the Ministry of Forestry as a policy actor.Footnote 945 Although Tanzanian Indigenous activists were also given an unprecedented opportunity to participate in the policy-making process around REDD+ by being invited to join a working group of the National REDD+ Taskforce, they were generally excluded from regional consultations on the development of a national REDD+ strategy and were unable to exert any influence on decision-making regarding REDD+. In this context, the fact that other Tanzanian domestic NGOs were advocating for the recognition and protection of the rights of forest-dependent communities, but not those of Indigenous Peoples, only reinforced the latter’s marginalization in the jurisdictional REDD+ policy-making process.Footnote 946

6.2 Rights and Project-Based REDD+ in Indonesia and Tanzania

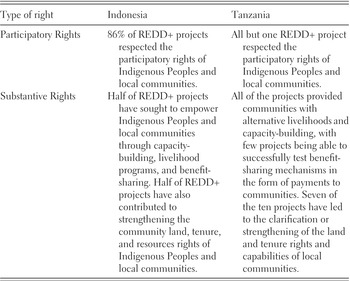

A comparison of my findings relating to the conveyance and construction of rights in the context of the development and implementation of REDD+ projects in Indonesia and Tanzania also yields interesting lessons. As discussed in Chapter 5, my analysis of the design and early outcomes of REDD+ projects in Indonesia and Tanzania shows that while most REDD+ projects have enacted and implemented legal norms relating to participatory rights and benefit-sharing, there is considerable variation across both countries in terms of the recognition and protection of forest, land tenure, and resource rights.

While it was not feasible for me to explain why and how these rights were conveyed and constructed across every single one of the thirty-eight REDD+ projects in my data set, I nonetheless formulated probable explanations that could account for broad trends in the recognition and protection of rights across these two countries. To begin with, I posited that the conveyance and construction of legal norms relating to participatory rights and benefit-sharing in the design and implementation of a majority of REDD+ projects in Indonesia and Tanzania could be primarily explained by the causal mechanisms of cost-benefit adoption, élite internalization, and cost-benefit commitment. In the first instance, given that most REDD+ projects were established with the aim of eventually generating carbon credits that could be sold on the voluntary carbon market through dual certification under the VCS and CCB, the requirements set by the CCB Standards appear to have been an important instrumental motivation for the proponents of REDD+ projects in Indonesia to enact and implement exogenous legal norms relating to participation and benefit-sharing. In the second instance, the proponents of REDD+ projects also enacted and implemented these legal norms because they had internalized that doing so was integral to the very success of their projects. As a result of a broader process of persuasive argumentation that has reshaped the field of conservation over the last two decades, many project developers understood that ensuring the participation of communities and sharing benefits with them was critical for guaranteeing their collaboration as well as ensuring the sustainability of REDD+ projects in the long-term. In the third instance, I argued that the conveyance of legal norms relating to participation and benefit-sharing ultimately triggered a process of construction in which these legal norms were adjusted to the particular context in which REDD+ projects were designed and implemented through the causal mechanisms of cost-benefit commitment. Indeed, whether and how to engage and empower local communities in the design and implementation of a REDD+ project can be expected to depend on numerous factors and the design of many REDD+ projects may be seen as resulting from the construction of hybrid legal norms in which exogenous legal norms are rationally calibrated and adjusted in order to craft redesigned solutions to achieve the objective of addressing the local drivers of deforestation and reducing carbon emissions from forest-based sources.Footnote 947

Table 6.2 Overview of the treatment of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and forest-dependent communities in the design and implementation of REDD+ projects in Indonesia and Tanzania

These three causal mechanisms also help explain why REDD+ projects in Indonesia and Tanzania have accorded very little attention to the distinctive status and rights of Indigenous Peoples. To begin with, the fact that the CCB Standards extend similar rights and protections to both Indigenous Peoples and local communities eliminated any market incentive for project developers to distinguish between these two categories in the design and implementation of REDD+ projects. Moreover, the shared understanding that many conservation practitioners held regarding the importance of engaging with and empowering local communities in REDD+ was primarily based on whether their collaboration was essential to the success of a project, whether or not they held the particular status of Indigenous Peoples. Finally, the distinction between Indigenous Peoples and local communities was not particularly relevant to the local context in which many REDD+ projects were implemented, especially in Tanzania, where none of the REDD+ projects were implemented on or near lands occupied or used by Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 948

Although most REDD+ projects have enacted or implemented legal norms relating to participation and benefit-sharing in broadly similar proportions in Indonesia and Tanzania, a key difference remains with respect to their implications for strengthening forest, land tenure, and resource rights. Most REDD+ projects in Tanzania sought to strengthen the forest and tenure rights of local communities and many succeeded in enhancing the land tenure of forest-dependent communities. By contrast, only half of REDD+ projects did so or sought to do so in Indonesia. I explained this divergence on the basis of two factors. First, while the CCB Standards create a clear market incentive to respect the participatory rights of local communities, to share benefits with them, and to not violate their forest and land tenure rights, the extent to which they actually incentivize the promotion of community forest rights and institutions is limited. Second, the divergent manner in which the proponents of REDD+ projects have addressed forest and land rights across these two countries has probably much to do with the costs and benefits of community forestry in comparison with other types of project interventions. Indeed, while the legal process for clarifying and resolving land and forest tenure issues in Indonesia is complex, cumbersome, and ineffective and is moreover pitted against powerful economic interests that stand to lose from the recognition and protection of community forest and resource rights, the process for securing community rights to forest lands and resources in Tanzania is much more straightforward and does not threaten any influential economic or political interests. And while strengthening community tenure or implementing community-based forest management makes eminent sense in a least-developed country like Tanzania where most drivers of deforestation are local in nature (such as local demand for energy and food), it does not necessarily amount to an effective strategy for addressing the large-scale drivers of deforestation in a middle-income country like Indonesia (such as palm oil plantations, logging, or mining).Footnote 949

In sum, I argue that the key divergences in the promotion of community forest, land tenure, and resource rights across project-based REDD+ activities in Indonesia and Tanzania can be best explained by the rational manner in which project developers designed their projects in light of endogenous legal norms and the particular challenges and opportunities offered for community forestry versus other types of interventions. In Tanzania, the legal process set out in the Forest Act and the local nature of drivers of deforestation meant that the promotion of community forest rights and tenure appeared to be an optimal solution for reducing carbon emissions through a REDD+ project. Conversely, the very different legal and political economic conditions that characterize forest governance in Indonesia would make community forestry a much less appealing option for the design of a REDD+ project.

6.3 Rights and REDD+ at Multiple Levels in Indonesia and Tanzania

An analysis of the implications of REDD+ for the recognition and protection of the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in Indonesia and Tanzania reveals the potential for the transnational legal process for REDD+ to yield convergent as well as divergent outcomes across levels of law within a particular country. On the one hand, the conveyance and construction of rights in the context of jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities in Tanzania had largely convergent effects. At the national level, the core strategies and activities envisaged in Tanzania’s National REDD+ Strategy were informed by, and seek to implement, the provisions on CBFM and JFM articulated in the Forest Act. Likewise, the REDD+ pilot projects pursued by nongovernmental actors provided the means and impetus to implement the same provisions at the local level. And while forest-dependent communities have largely gained from the pursuit of jurisdictional and project-based REDD+ activities in Tanzania, Indigenous Peoples have been largely ignored by these same activities and have not benefited from an opportunity to use REDD+ as a vehicle to gain greater recognition for their status, role, and rights in the governance of forests in Tanzania.

On the other hand, my research suggests that various forms of REDD+ have had divergent implications for the rights of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in Indonesia. To be sure, Indigenous Peoples have made important gains from the pursuit of jurisdictional REDD+ activities, especially because their distinctive status and rights have been recognized in both Indonesia’s National REDD+ Strategy and its policy on social and environmental safeguards. In addition, Indigenous activists and communities now have an opportunity to advocate for the recognition of their substantive rights to forests, land tenure, and resources as a result of these new policy commitments and the creation of new mechanisms for the clarification of forest tenure and the resolution of land disputes. On the other hand, Indigenous Peoples have made few gains from the development and implementation of REDD+ projects at the local level. Not only have most projects generally failed to increase the land tenure security of Indigenous Peoples in Indonesia, but the few projects that have done so have sought to implement licenses for community forestry and ecosystem restoration as opposed to pressing for the recognition of the customary forest and land rights of adat communities.

Ultimately, the broader lesson that can be drawn from a comparison of my findings on the intersections between REDD+ and rights in Indonesia and Tanzania concerns the persistent role that the path-dependence of national sites of law has played in shaping or limiting the influence of the transnational legal process for REDD+. My study of jurisdictional REDD+ readiness activities in Tanzania revealed how an existing endogenous norm (to the effect that there are no Indigenous Peoples in Tanzania) hindered the transplantation of exogenous legal norms relating to Indigenous rights and led to the construction of hybrid legal norms extending these rights to forest-dependent communities. To a lesser extent, the recognition of the rights of local communities, alongside those of Indigenous Peoples, in the context of Indonesia’s jurisdictional REDD+ policies also revealed the resilience of similar endogenous norms that led to the translation, rather than the transplantation, of Indigenous rights norms. Existing national laws and the political economy of national forest governance were also shown to have exerted influence on the manner in which legal norms were constructed in each country. In Tanzania, the transnational legal process for REDD+ reinforced, and was ultimately shaped by, endogenous legal norms that enabled villages to obtain formal rights to manage and control forests and their resources on village lands. It was also enabled by the perception of community forestry as a cost-effective way of addressing the local drivers of deforestation and the fact that this approach did not arouse strong opposition from powerful economic and political interests. Conversely, the complex, ineffective, and uncertain set of laws, policies, and processes for clarifying and resolving land and forest tenure issues in Indonesia significantly limited the ability for project-based REDD+ activities to enhance the protection and recognition of community forest and resource rights. Only time will tell whether these same factors will bedevil the ability for the National REDD+ Agency to implement the May 2013 Constitutional Ruling recognizing the customary forest tenure rights of masyarakat adat. In sum, a cross-level analysis of the relationship between REDD+ and rights in Indonesia and Tanzania reveals the extent to which the ultimate effects of the transnational legal process for REDD+ has the potential to transcend, as well as be shaped by, national law and politics.Footnote 950