Obesity has been identified as a significant health concern in the 21st century( Reference Nishtar, Gluckman and Armstrong 1 , 2 ). Poor dietary practices developed in childhood have been identified as a critical contributor to the development of preventable lifestyle diseases, including overweight and obesity and CVD( Reference Victora 3 , Reference Simmonds, Burch and Llewellyn 4 ). In Australia, over one-quarter of adolescents are overweight or obese( 5 ). The importance of developing a healthy dietary behaviour during adolescence is critical in the prevention of obesity( Reference Victora 3 ).

Healthy dietary intake is essential for physical development, growth and normal weight management throughout adolescence( 2 ). Adolescents aged 12–18 years are advised to consume three servings of fruit and four servings of vegetables each day( 6 ). Globally and in Australia, the majority of adolescents do not consume sufficient fruit and vegetables, instead consuming high-fat, energy-dense, nutrient-poor foods( Reference Savige, Ball and Worsley 7 , Reference Bauer, Larson and Nelson 8 ). Among adolescents aged 14–18 years, nearly three-quarters (73 %) were consuming below the recommended guideline amounts and over half (59 %) were having fewer than 1·5 servings of fruit and vegetables daily, including 41 % who usually consumed less than 1 serving/d( 5 ).

In response to the prevalence of inadequate dietary practices among adolescents, secondary schools have implemented numerous healthy food policies to promote healthy dietary behaviours( Reference Lawlis, Knox and Jamieson 9 , Reference Micha, Karageorgou and Bakogianni 10 ). However, interventions focusing on improving food and nutrition knowledge have been limited to changing only short-term dietary behaviour( Reference Vézina-Im, Beaulieu and Bélanger-Gravel 11 ). Food literacy is a relatively new and emerging concept used to describe a range of skills and knowledge around food, its uses, and daily dietary behaviours associated with healthy eating( Reference Krause, Sommerhalder and Beer-Borst 12 ). The term ‘food literacy’ is defined as: ‘a collection of interrelated knowledge, skills, and behaviours required to plan, manage, select, prepare and eat foods to meet needs and determine food intake’( Reference Vidgen and Gallegos 13 ) (p. 72). This term has been used increasingly in food and nutrition policy and research. Food literacy has emerged as a framework to connect food-related knowledge, cooking skills, and capacity to foster and develop food and nutritional knowledge to assist in changing dietary behaviour( Reference Colatruglio and Slater 14 ).

Critical attributes of food literacy consist of nutrition knowledge, cooking skills, eating behaviours, knowledge of where food originates from and the ability to prepare healthy nutritious foods( Reference Vidgen and Gallegos 15 ). The school environment has been identified by the WHO as an ideal setting in which youth consume approximately one-third to one-half of their daily food intake( Reference Regan, Parnell and Gray 16 , 17 ). Research exploring food literacy in secondary schools has emerged as a promising approach to fostering healthy dietary behaviours and educating students on health literacy knowledge( Reference St Leger 18 ). Research into schools adopting a health-promoting approach suggests that nutrition programmes using a health-promoting school approach can increase participants’ consumption of high-fibre foods, healthier snacks, water, milk, fruit and vegetables( Reference Wang and Stewart 19 ). Primary studies examining the effectiveness of food literacy programmes and interventions have identified an overall increase in nutrition-related knowledge and cooking skills, but minimal change in long-term healthy dietary behaviours( Reference Brooks and Begley 20 , Reference Vaitkeviciute, Ball and Harris 21 ).

To date, only two literature reviews have explored food literacy programmes in secondary schools and the relationship between food literacy and dietary intake for adolescents( Reference Brooks and Begley 20 , Reference Vaitkeviciute, Ball and Harris 21 ). Brooks and Begley( Reference Brooks and Begley 20 ) explored the effectiveness of food literacy programmes targeting adolescents, their food literacy components and programme effectiveness in predominantly in Western countries. Vaitkeviciute et al. ( Reference Vaitkeviciute, Ball and Harris 21 ) conducted a systematic review from a global perspective to investigate the relationship between food literacy and adolescents’ dietary intake, and identified that food literacy might play a role in shaping adolescents’ dietary intake. Furthermore, the review identified that more rigorous research methods are required to assess the causality between food literacy and adolescent dietary intake to confirm the extent of the relationship( Reference Vaitkeviciute, Ball and Harris 21 ). Schoolyard garden programmes targeted to adolescents are emerging as a potential strategy in the school setting to increase preference for and improve dietary intake of fruit and vegetables( Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Story and Heim 22 ). Reviewing interventions in the school environment with the addition of a school-based garden and students’ and home-economics teachers’ attitudes and perceptions of food literacy interventions may provide an additional insight into the field of food literacy. Given the fact that food literacy has emerged recently in academia and government policies as an essential topic over the past decade, a comprehensive overview of studies that report on the effects and perceptions of food literacy interventions in secondary schools would provide an insight into food literacy interventions in secondary schools( Reference Dixon-Woods, Fitzpatrick and Roberts 23 , Reference Jackson and Waters 24 ).

The primary aim of the current review was to synthesise the literature on food literacy interventions in secondary schools and report on the associations among adolescents. Second, the review aimed to explore adolescents’ and home-economics teachers’ perceptions of food literacy interventions in secondary schools and their effects on dietary outcomes. Home-economics teachers predominantly provide education on culinary skills, food and nutrition in secondary schools. Although on a global scale culinary skills and nutrition can be taught by other topics in schools, home economics is the dominant topic in which food literacy can be taught in the secondary-school setting. Therefore, the objectives of the current review were to:

1. Report on the effect of food literacy interventions conducted in a secondary-school setting.

2. Explore adolescents’ attitudes and perceptions of food literacy programmes and the topic of home economics.

3. Explore home-economics teachers’ perspectives on food literacy programmes and the topic of home economics.

Methods

The current systematic literature review is registered with PROSPERO, the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42017074204). As food literacy is a relatively new emerging term, changes were made to the protocol registered on PROSPERO. Our original inclusion criteria were: (i) studies focused on adolescents with low literacy; and (ii) to report valid and reliable measures of food literacy. However, as the review unfolded, two things became clear: in many cases, the evidence adhering to these two requirements is sparse given the notable diversity of study designs and intervention outcomes on food literacy research. Second, we could not gain critical insight from the parameters that we initially set. We therefore extended our criteria to a broader range of literature focusing on qualitative studies exploring secondary-school food literacy interventions regarding the social, biochemical and non-nutritional aspects.

A comprehensive systematic literature review search was conducted following the reporting recommendations outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement( Reference Moher, Liberati and Tetzlaff 25 ). As recommended in the PRISMA statement, we completed the standard PRISMA checklist to provide further details of the implementation of the study (see online supplementary material). For the present systematic review, ‘food literacy’ was defined as ‘a collection of inter-related knowledge, skills and behaviours required to plan, manage, select, prepare and eat foods to meet needs and determine food intake’( Reference Vidgen and Gallegos 13 ) (p. 54). In light of the ubiquitous term of food literacy, the key components and attributes that the review focuses on are cooking skills, dietary behaviours, healthy food choices, food culture and knowledge.

Databases and keywords

The emerging concept of food literacy broadly consists of food and nutrition knowledge, skills and capacity to assist in making informed food choices and improve dietary behaviours( Reference Krause, Sommerhalder and Beer-Borst 12 ). Due to the multifaceted definition of food literacy, relevant search terms based on each component of food literacy were informed by the food literacy definition of Vidgen and Gallegos( Reference Vidgen and Gallegos 13 ) and encompass the following factors: knowledge, skills and behaviours with food planning, management, selection, preparation and eating. The following databases were selected as they offer broad coverage of allied health topics, including nutrition and public health literature: Medline, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Scopus and Web of Science (Science Citations Index and Social Citations Index). All electronic databases were searched from the earliest record to present. The PICOS (problem, intervention, comparison, outcome and setting) approach was applied to the quantitative and qualitative search( Reference Santos, Pimenta and Nobre 26 ). For quantitative studies: problem = (effects of food literacy interventions), intervention = (food literacy intervention), outcome = (behaviours, healthy food choices, culture) and setting = (interventions conducted in secondary schools). For qualitative studies, the PICOS was reformulated with outcome = (changes in, or perceptions about, food literacy in secondary schools, or associations between food literacy and dietary intake and perceptions about secondary school-based food literacy programmes).

Students attending primary schools and/or outside the age range of 10–19 years were excluded from the study. Primary schools in some countries may end at age 12 years; middle school may consist of youth aged 12–14 years; and high school may end at the age of 16–17 years. To ensure that only students in secondary schools were included, the age of the participants was identified as the key exclusion criterion. Search terms and MeSH headings in the title, abstract and index terms were initially identified in SCOPUS, and the resulting keywords were used for the remaining databases (Table 1). An academic librarian who had expertise in health-related literature assisted with the development of MeSH headings and keywords, and wild cards were applied to words in the plural.

Table 1 SCOPUS search strategy

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the current systematic review if they met the following inclusion criteria: (i) peer-reviewed and primary, original research; (ii) written in English; (iii) adolescents aged between 10 and 19 years old; (iv) the outcome of a programme related to an improvement in dietary habits, healthy food choices, nutrition knowledge and cooking skills; (v) cross-sectional, mixed-methods, quantitative and or qualitative; and (vi) no restriction on the year of publication. Studies were excluded if they were a personal opinion; a systematic review and meta-analysis; and if they focused on disease-related nutrition interventions for adolescents, such as for obesity, anorexia nervosa or type 2 diabetes mellitus, or included participants with dietary, medical conditions, mental health conditions and learning difficulties.

Procedures and synthesis

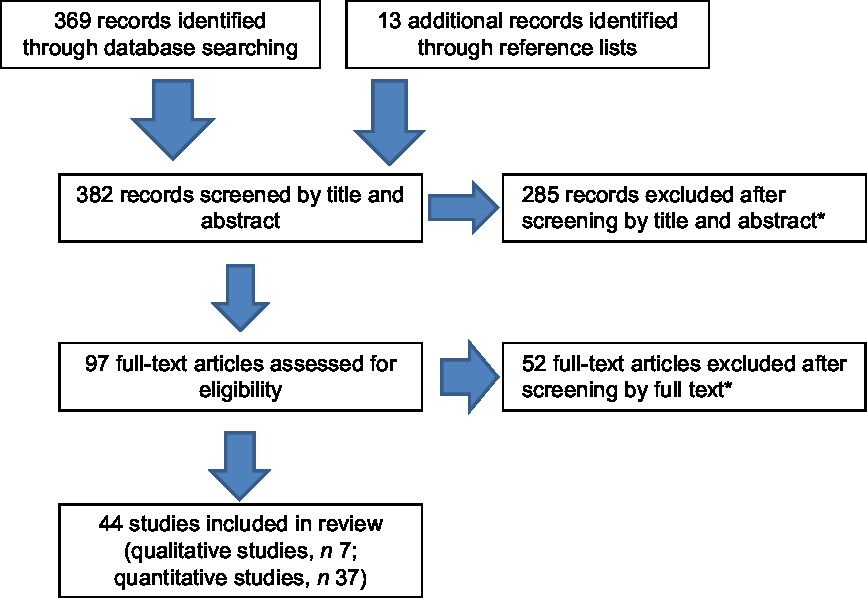

One researcher (C.J.B.) conducted the systematic literature search, full-text screening and extraction of studies. A PRISMA flow diagram was used to document the systematic review’s search and selection process of studies for inclusion (see Fig. 1). A list of potentially relevant articles from each database was identified, exported and saved into EndNote® version X8. Duplicates were identified and removed; potentially relevant articles were scanned to confirm relevance for full review by two authors independently (C.J.B. and P.R.W.). Both researchers (C.J.B. and P.R.W.) independently assessed and extracted the quantitative and qualitative data from papers included in the review using the standardised data extraction tool JBI-MASt-ARI and JBI-QARI, respectively( 27 ). Two independent reviewers conducted each stage of the review. Any reviewer conflicts were discussed to arrive at a consensus decision with the aid of the third reviewer (M.J.D). Ineligible articles were removed from the list after noting the reason for exclusion. Due to the various study designs and outcome measures, a meta-analysis was not conducted.

Fig. 1 Flow diagram of information through the different phases of the review: flowchart of the literature search and review process. *Reasons for exclusion: study population not adolescents (adults or young children, n 70); study did not address the main objective of the present review (n 246); study was conducted outside the secondary-school setting (n 14); study was in the form of a poster or a personal opinion publication (n 4); study was in the form of a literature review, eating disorders or PhD thesis (n 4)

Outcomes assessed

The effects of food literacy interventions were based on measures of dietary outcomes (such as changes in students’ nutrition knowledge, cooking self-efficacy, fruit and vegetable choice, preference and consumption) and dietary intake (dietary recalls, FFQ) was assessed. Qualitative research was investigated to understand adolescents’ and home-economics teachers’ attitudes, understandings and perspectives on food literacy programmes in the secondary-school environment.

Risk of bias assessment

Studies were assessed for risk of bias in methodological quality by two independent researchers (C.J.B. and P.R.W.). The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Quality Criteria Checklist (QCC)( 28 ) was utilised to check the risk of bias in the included quantitative studies. The QCC consists of ten criteria that assess the quality of each quantitative study. The QCC tool was used to assess the scientific rigour of included quantitative nutritional studies. Each study’s attributes were assessed by the QCC and were classified as positive, negative or neutral. An overall quality score was given to each individual study. If individual QCC criteria were not appropriate, the overall score was based only on the appropriate QCC criteria. Qualitative studies were assessed for their methodological rigour and quality based on the critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies provided by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence( 29 ). The checklist includes fourteen criteria under the following domains: the theoretical approach and clarity of its aims; the rigour of the methods; how well the data collection was carried out; the relationship between the researcher and participants and reliability of the methods; the richness of the data and rigour and reliability of the analysis and findings; and the reporting of ethical issues( 29 ).

Results

A total of 382 papers were retrieved from five databases. From these studies, 285 did not qualify for review as they were not relevant to the topic, did not incorporate adolescents, the interventions were not conducted on school grounds or were not of empirical evidence (e.g. personal opinions). A full-article review was conducted on the remaining ninety-seven articles, after which fifty-two articles did not meet all the criteria and were excluded. Forward and backward searching, as well as a screening of Brooks and Begley( Reference Brooks and Begley 20 ) and Vaitkeviciute et al.( Reference Vaitkeviciute, Ball and Harris 21 ), resulted in a total of forty-four publications (qualitative studies, n 7; quantitative studies, n 37). The flow diagram of the systematic review is presented in Fig. 1. A narrative synthesis was used to report the associations of the findings.

Overview of studies

The studies in the systematic review were published between 1990 and early 2017. Studies were conducted in Australia (n 10)( Reference Ronto, Ball, Pendergast and Harris 30 – Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 39 ), Canada (n 1)( Reference Slater 40 ), China (n 1)( Reference Zhou, Xu, Li and Sharma 41 ), France (n 1)( Reference Turnin, Buisson and Ahluwalia 42 ), Greece (n 2)( Reference Petralias, Papadimitriou and Riza 43 , Reference Tsartsali, Thompson and Jago 44 ), Iran (n 1)( Reference Mirmiran, Azadbakht and Azizi 45 ), South Africa (n 1)( Reference Venter and Winterbach 46 ), South India (n 1)( Reference Swaminathan, Thomas and Kurpad 47 ), Kenya (n 1)( Reference Gewa, Murphy and Weiss 48 ), Norway (n 2)( Reference Klepp and Wilhelmsen 49 , Reference Øverby, Klepp and Bere 50 ), Portugal (n 1)( Reference Leal, de Oliveira and Rodrigues 51 ), Denmark (n 1)( Reference Osler and Hansen 52 ), Northern Ireland (n 1)( Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 53 ), the USA (n 17)( Reference Chatterjee, Daftary and Campbell 54 – Reference Williams, DeSorbo and Sawyer 70 ), the UK (n 1)( Reference Caraher, Seeley and Wu 71 ) and Sweden (n 2)( Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 72 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 73 ).

Study designs included cross-sectional (n 16), quasi-experimental (n 13), pre–post intervention (n 1), randomised controlled trial (n 1) and longitudinal cohort study (n 1), observational (n 1), mixed methods (n 4) and qualitative (n 7). The number of adolescent participants ranged from twenty-two to 1488. The number of home-economics staff ranged from five to 118. Tables 2 and 3 provide an overview of the included studies, consisting of: country in which the study was conducted; study design; target group/sample size; duration of programme; theoretical underpinning; dietary outcome measure; food literacy attributes; and key findings.

Table 2 Summary of quantitative studies included in the current systematic review on food literacy programmes in secondary schools

SCT, Social Cognitive Theory; TPB, Theory of Planned Behaviour; HBM, Health Belief Model; ANGELO, Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity; TM, Transtheoretical Model; TRA, Theory of Reasoned Action; F&V, fruit(s) and vegetable(s); FSD, food service director; SES, socio-economic status.

Table 3 Qualitative studies included in the current systematic review that focus on adolescents’ and home-economics teachers’ attitudes and perceptions of food literacy programmes in secondary schools

SES, socio-economic status.

Risk of bias assessment

Table 4 provides an overall risk score for the quantitative studies. The majority of quantitative studies were identified as positive, with two studies being average( Reference Mirmiran, Azadbakht and Azizi 45 , Reference Huang, Kaur and McCarter 59 ) in rating quality. Table 5 provides an overall evidence grading for the qualitative studies. The majority of studies were identified as positive ‘++’, with one being ‘+’( Reference Swaminathan, Thomas and Kurpad 47 ).

Table 4 Quality assessment attributes for each quantitative study included in the current systematic review, assessed by the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics’ Quality Criteria Checklist( 28 )

N/A, not applicable (due to study design); +, positive overall score; NR, not reported; −, negative overall score (this score is given if criterion is not met).

Table 5 Quality appraisal for each qualitative study included in the current systematic review, assessed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies( 29 )

Grading the evidence:

++ All or most of the quality criteria have been fulfilled. Where they have been fulfilled the conclusions of the study or review are thought very unlikely to alter.

+ Some of the criteria have been fulfilled. Where they have been fulfilled the conclusions of the study or review are thought unlikely to alter.

− Few or no criteria fulfilled. The conclusions of the study are thought likely or very likely to alter.

Quantitative and mixed-methods studies

Programme type and duration

Thirty-seven quantitative or mixed-methods studies were identified. They consisted of practical cooking classes (n 5)( Reference Gans, Levin and Lasater 58 , Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma 60 , Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg 61 , Reference Schober, Carpenter and Currie 68 , Reference Caraher, Seeley and Wu 71 ), reading nutritional labels (n 2)( Reference Huang, Kaur and McCarter 59 , Reference Williams, DeSorbo and Sawyer 70 ), school-based gardens (n 5)( Reference Jaenke, Collins and Morgan 34 , Reference Morgan, Warren and Lubans 35 , Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 , Reference McAleese and Fada 64 , Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 ), school supplementary food programmes (n 1)( Reference Gewa, Murphy and Weiss 48 ), technology interventions (n 6)( Reference Turnin, Buisson and Ahluwalia 42 , Reference Petralias, Papadimitriou and Riza 43 , Reference Gewa, Murphy and Weiss 48 , Reference Long and Stevens 63 , Reference Miller 65 ), lectures about nutritional education and food safety (n 14)( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Slater 40 , Reference Zhou, Xu, Li and Sharma 41 , Reference Tsartsali, Thompson and Jago 44 – Reference Venter and Winterbach 46 , Reference Klepp and Wilhelmsen 49 – Reference Osler and Hansen 52 , Reference Chapman, Toma and Tuveson 56 , Reference Laska, Larson and Neumark-Sztainer 62 , Reference Pirouznia 66 , Reference Trexler and Sargent 69 ), and home-economics teachers’ perspectives on food literacy in secondary schools (n 6)( Reference Ronto, Ball, Pendergast and Harris 30 – Reference Dewhurst and Pendergast 32 , Reference Pendergast and Dewhurst 36 , Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 38 , Reference Slater 40 ). Duration of the interventions varied and was dependent on the type of study intervention and aspects of food literacy being investigated. The shortest duration of a study was 1 week( Reference Schober, Carpenter and Currie 68 ) and the most extended duration of a study was 10 years( Reference Laska, Larson and Neumark-Sztainer 62 ).

Theoretical basis for programme development

Theoretical underpinnings used in the studies were Social Cognitive Theory (n 5)( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 , Reference Long and Stevens 63 , Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 , Reference Williams, DeSorbo and Sawyer 70 ), the Transtheoretical Model (n 1)( Reference Long and Stevens 63 ), the Health Belief Model (n 1)( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 ), the Theory of Planned Behaviour (n 1)( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 ) and the Analysis Grid for Environments Linked to Obesity planning model (n 1)( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 39 ).

The review identified four broad approaches in how food literacy programmes have been administered in secondary schools: (i) food knowledge and change in dietary intake and behaviour (self-efficacy)( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Pendergast and Dewhurst 36 , Reference Turnin, Buisson and Ahluwalia 42 , Reference Tsartsali, Thompson and Jago 44 , Reference Venter and Winterbach 46 , Reference Gewa, Murphy and Weiss 48 – Reference Øverby, Klepp and Bere 50 , Reference Osler and Hansen 52 , Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg 61 , Reference Long and Stevens 63 , Reference Trexler and Sargent 69 ); (ii) garden-based interventions( Reference Jaenke, Collins and Morgan 34 , Reference Morgan, Warren and Lubans 35 , Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 , Reference McAleese and Fada 64 , Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 ); (iii) gendered differences and nutritional knowledge and behaviour( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Jaenke, Collins and Morgan 34 , Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 39 , Reference Mirmiran, Azadbakht and Azizi 45 , Reference Venter and Winterbach 46 , Reference Klepp and Wilhelmsen 49 , Reference Chapman, Toma and Tuveson 56 , Reference Huang, Kaur and McCarter 59 , Reference Miller 65 , Reference Pirouznia 66 ); and (iv) adolescent( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 37 , Reference Swaminathan, Thomas and Kurpad 47 , Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 53 – Reference Lukas and Cunningham-Sabo 55 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 72 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 73 ) and home-economics staff perspectives on food literacy( Reference Ronto, Ball, Pendergast and Harris 30 – Reference Dewhurst and Pendergast 32 , Reference Pendergast and Dewhurst 36 , Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 38 – Reference Slater 40 ).

Observational and intervention studies

Food knowledge and change in dietary intake and behaviour (self-efficacy)

Nine studies investigated the relationship between food knowledge and dietary intake( Reference Tsartsali, Thompson and Jago 44 , Reference Venter and Winterbach 46 , Reference Gewa, Murphy and Weiss 48 , Reference Øverby, Klepp and Bere 50 , Reference Osler and Hansen 52 , Reference Chapman, Toma and Tuveson 56 , Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg 61 , Reference Long and Stevens 63 , Reference Trexler and Sargent 69 ) and five studies investigated food knowledge and behaviour( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Turnin, Buisson and Ahluwalia 42 , Reference Klepp and Wilhelmsen 49 , Reference Leal, de Oliveira and Rodrigues 51 , Reference Trexler and Sargent 69 ). Eight studies showed a positive impact of knowledge( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Tsartsali, Thompson and Jago 44 , Reference Venter and Winterbach 46 , Reference Leal, de Oliveira and Rodrigues 51 , Reference Osler and Hansen 52 , Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg 61 , Reference Long and Stevens 63 , Reference Pirouznia 66 ). One study showed a negative impact on nutritional knowledge and dietary intake( Reference Mirmiran, Azadbakht and Azizi 45 ). Two studies were not able to indicate a clear relationship between food knowledge and dietary intake( Reference Chapman, Toma and Tuveson 56 , Reference Trexler and Sargent 69 ).

Two studies investigated adolescent reading ability and nutrition labels( Reference Huang, Kaur and McCarter 59 , Reference Williams, DeSorbo and Sawyer 70 ). One study identified that nutrition label reading ability does not relate to healthier diets among adolescents( Reference Huang, Kaur and McCarter 59 ). Adolescent boys’ reading of nutrition labels was associated with higher fat intake( Reference Huang, Kaur and McCarter 59 ). One study investigated the effects of a culturally targeted energy labelling intervention on food purchasing behaviour and found that after the intervention, there was a mean decline in purchased energy of 20 % and unhealthy foods( Reference Williams, DeSorbo and Sawyer 70 ).

Garden-based nutrition interventions

Five studies investigated the relationship between school-based garden interventions and fruit and vegetable consumption. Four of the five studies demonstrated positive results( Reference Morgan, Warren and Lubans 35 , Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 , Reference McAleese and Fada 64 , Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 ). One study showed an overall increase from a 10-week intervention with nutrition education and garden for overall willingness to taste vegetables (P < 0·001) and overall taste ratings of vegetables (P < 0·001)( Reference Morgan, Warren and Lubans 35 ). Three studies showed a higher fruit and vegetable intake and preference, self-efficacy and knowledge( Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 , Reference McAleese and Fada 64 , Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 ). One study showed an overall increase in fruit consumption (before to after) by 1·12 servings (P < 0·001) for students at experimental school 2, and vegetable consumption increased significantly by 1·44 servings (P < 0·001)( Reference McAleese and Fada 64 ). The intervention consisted of a control group and two treatment groups. One group consisted of a 12-week nutrition programme and the other treatment group consisted of garden-based activities. Adolescents who participated in garden-based activities had a significant increase in vitamin A, vitamin C and fibre intake( Reference McAleese and Fada 64 ). One study was not able to show any significant difference in fruit and vegetable intake between genders( Reference Jaenke, Collins and Morgan 34 ).

Gender differences in nutritional knowledge and dietary behaviour

Nine studies investigated gender differences on the impact of nutrition knowledge and fruit and vegetable intake( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Jaenke, Collins and Morgan 34 , Reference Mirmiran, Azadbakht and Azizi 45 , Reference Venter and Winterbach 46 , Reference Klepp and Wilhelmsen 49 , Reference Chapman, Toma and Tuveson 56 , Reference Huang, Kaur and McCarter 59 , Reference Miller 65 , Reference Pirouznia 66 ). Four studies revealed that females have greater nutritional knowledge than males( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Mirmiran, Azadbakht and Azizi 45 , Reference Venter and Winterbach 46 , Reference Pirouznia 66 ). One study found a gender difference only in fruit and vegetable preferences, with girls rating carrot higher than boys in taste ratings (P = 0·04)( Reference Jaenke, Collins and Morgan 34 ). One study identified that although both boys and girls had a reasonable level of nutritional knowledge, only boys had good nutritional practices( Reference Mirmiran, Azadbakht and Azizi 45 ). Two studies investigated nutrition education and behaviour changes. One study explored milk and yoghurt selection in a school breakfast programme and reported females were more likely to choose yoghurt than males( Reference Miller 65 ). One study assessed healthy eating behaviour and healthy eating knowledge before and after the intervention at 5- and 12-month follow-ups( Reference Klepp and Wilhelmsen 49 ). The results of the study showed that there was a short-term positive effect on eating behaviours in males, as well as maintaining a positive impact on healthy eating knowledge.

The effectiveness of cooking and food safety

Six studies investigated cooking skills and food safety( Reference Zhou, Xu, Li and Sharma 41 , Reference Gans, Levin and Lasater 58 , Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma 60 , Reference Larson, Story and Eisenberg 61 , Reference Schober, Carpenter and Currie 68 , Reference Caraher, Seeley and Wu 71 ). Four out of five studies utilised experienced chefs and hands-on cooking with the adolescents( Reference Gans, Levin and Lasater 58 , Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma 60 , Reference Schober, Carpenter and Currie 68 , Reference Caraher, Seeley and Wu 71 ) and only one study used lectures and prize-based games about nutrition and food safety( Reference Zhou, Xu, Li and Sharma 41 ). Studies that utilised experimental cooking and nutritional education programmes led by chef instructors showed positive results in overall cooking confidence, cooking skills and tasting new foods( Reference Caraher, Seeley and Wu 71 ). One study found that experimental cooking and nutrition education programmes led by chef instructors might be an effective way to improve nutrition in low-income communities( Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma 60 ). Nutritional knowledge score increased from 0·6 to 0·8, cooking self-efficacy score from 3·2 to 3·6, and vegetable consumption score from 2·2 to 2·4 (all P < 0·05). Increased score for communication about healthy eating (4·1 to 4·4; P < 0·05) was observed 6 months after the end of the course( Reference Jarpe-Ratner, Folkens and Sharma 60 ). One study investigated the effects of the LiveWell@School Food Initiative in Colorado and identified an increase in the proportion of fresh, from-scratch cooking foods (using fresh ingredients compared with cooking using processed foods) and a decrease in energy, fat, saturated fat and sodium that contributed to a healthier school food environment( Reference Schober, Carpenter and Currie 68 ). One study investigated the effectiveness of a school-based nutrition and food safety education programme among primary- and junior-high-school students in China( Reference Zhou, Xu, Li and Sharma 41 ). It found that after adolescents participated in the school-based cooking programme, they enjoyed tasting new foods, making new meals and learning new cooking skills. Participants reported an increase in their food skills, following recipes and preparing foods.

Qualitative studies

Adolescent attitudes and perceptions on food literacy

Seven studies investigated adolescents and their attitudes about cooking classes in secondary schools and their understanding of healthy and unhealthy eating( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 37 , Reference Swaminathan, Thomas and Kurpad 47 , Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 53 – Reference Lukas and Cunningham-Sabo 55 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 72 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 73 ). Two studies specifically investigated adolescents’ attitudes and views on school cooking interventions( Reference Chatterjee, Daftary and Campbell 54 , Reference Lukas and Cunningham-Sabo 55 ). Lukas and Cunningham-Sabo’s study conducted focus groups interviews with students to obtain the classroom experiences about the Cooking with Kids programme( Reference Lukas and Cunningham-Sabo 55 ). The findings from this study were that students described positive experiences with the programme and its curriculum integration into academic subjects. Another study investigated students’ perspectives on a high-school food programme and identified that all stakeholders appreciated the programme, but there were some disagreements regarding the impression of how cooking skills are taught to students regarding culturally incompatible foods( Reference Chatterjee, Daftary and Campbell 54 ).

Five studies investigated adolescents’ perceptions of healthy and unhealthy eating by qualitative research methodology( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 37 , Reference Swaminathan, Thomas and Kurpad 47 , Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 53 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 72 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 73 ). The overall consensus of adolescents’ attitudes towards healthy eating was ‘fruit’, ‘vegetable’ and ‘salads’ were viewed as healthy and processed foods were viewed as less-healthy foods( Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 53 ). A potential barrier identified in one study was that adolescents are interested in developing food skills but have limited opportunities to develop these skills in school or the home environment( Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 53 ). One study investigated adolescents’ perspectives on food literacy and its impact on their dietary behaviours. Adolescents were required to rank twenty-two aspects of food literacy in order of importance. Adolescents ranked food and nutrition knowledge as more important than food skills and food capacity( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 37 ).

Home-economics teachers’ perspectives on home economics subjects in secondary schools

Seven studies investigated home economics in secondary schools and teachers’ perspectives on home economics in secondary schools( Reference Ronto, Ball, Pendergast and Harris 30 – Reference Dewhurst and Pendergast 32 , Reference Pendergast and Dewhurst 36 , Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 38 – Reference Slater 40 ). One study explored home-economics teachers’ views on the role of secondary schools in enhancing adolescents’ food literacy and promoting healthy dietary behaviour( Reference Ronto, Ball, Pendergast and Harris 30 ). They identified cooking skills, knowledge about healthy foods, and food safety and hygiene practices as very important. The overall consensus regarding barriers and perceptions on home economics in secondary schools was: lack of teaching materials and facilities, less importance of home economics compared with science and maths-based subjects, no supportive school canteens and negative role modelling of staff( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 38 ).

Dietary behaviour outcome measures

In studies that measured dietary intake, this was done by FFQ (n 11), 24 h dietary recalls (n 6), KIDMED Index (n 2), other questionnaires and surveys (n 27), interviews (n 2), focus groups (n 4), audio/video-taping (n 2), and observations and checklists (n 2).

Discussion

The purposes of the current systematic review were to provide a recent and comprehensive overview of worldwide studies on the effects of food literacy programmes in secondary schools, and on adolescents’ and home-economics teachers’ attitudes and perspectives on food literacy programmes in secondary schools. No study used a valid and reliable food literacy tool. There has been increasing consideration of food literacy as a significant influence on children and young people’s eating patterns( Reference Doustmohammadian, Omidvar and Keshavarz-Mohammadi 74 , Reference Perry, Thomas and Samra 75 ). Previous studies investigating the implementation and effectiveness of school-based nutrition promotion programmes using a health-promoting schools approach have identified that the school environment, via home economics, can provide an ideal setting for the teaching and practice of food literacy skills and healthy dietary behaviour( Reference Wang and Stewart 19 ). For the present review, we aimed to extend previous systematic reviews( Reference Brooks and Begley 20 , Reference Vaitkeviciute, Ball and Harris 21 ) on this topic and to include areas where further research is needed.

The effects of secondary-school food literacy interventions were challenging to assess because of varying study designs, intervention strategies, research aims and outcome measures, resulting in inconsistencies in the overall findings of food literacy. Furthermore, it was difficult to determine which type of school-based programme or intervention was most effective. Of the forty-four studies included in the review, interventions that were implemented for a minimum of 4 weeks and had used a validated and reliable evaluation measure that incorporated psychological constructs such as self-efficacy and knowledge were found to show changes in short-term dietary behaviour.

The quality of studies included in the current review should be considered when interpreting their findings. The majority of quantitative studies were identified as positive, with two studies being average( Reference Mirmiran, Azadbakht and Azizi 45 , Reference Huang, Kaur and McCarter 59 ) in rating quality. Although randomised controlled trials should provide more reliable evidence on the effects of interventions( Reference Higgins, Altman and Gøtzsche 76 ), the one randomised controlled trial included( Reference Gewa, Murphy and Weiss 48 ) did not show greater quality than the quasi-experimental or observational or mixed-method studies. The majority of qualitative studies were identified as positive (‘++’), with one being ‘+’( Reference Swaminathan, Thomas and Kurpad 47 ). The findings suggest that food literacy studies typically satisfy quality requirements.

Regarding sample size, only two out of twenty-five interventions reported conducting a statistical power calculation( Reference Jaenke, Collins and Morgan 34 , Reference Morgan, Warren and Lubans 35 ). Since the studies reviewed used a convenience sample, with only two studies reporting a power calculation; only reporting P values with minimal mention of standard deviations and effect sizes, as such the results from these studies should be interpreted with caution. All of the studies used self-reported dietary intake as the outcome measure, which may have resulted in some potential respondent bias. Of the twenty-five interventions, seven studies did not describe the participant withdrawal/dropout or response rate in their studies; and only one study discussed a blinding procedure( Reference Gewa, Murphy and Weiss 48 ). Only one study out of twenty-three demonstrated long-term dietary behaviour from adolescence to adulthood. From the studies examined, it is not clear whether the observed effects were long term regarding changes in dietary behaviour.

Of the articles reviewed, only nine studies explicitly stated a theoretical underpinning in their design( Reference Gracey, Stanley and Burke 33 , Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 38 , Reference Klepp and Wilhelmsen 49 , Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 , Reference Long and Stevens 63 , Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 , Reference Williams, DeSorbo and Sawyer 70 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 72 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 73 ), with the most popular theoretical underpinning being the Social Cognitive Theory. Theory-driven interventions typically demonstrated more associations with changes in positive dietary behaviour compared with other studies( Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 , Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 ).

The present review identified there is a paucity of studies showing secular dietary behaviours of food literacy interventions. Laska et al.’s( Reference Laska, Larson and Neumark-Sztainer 62 ) longitudinal study investigated the involvement in food preparation, showing that it tracks over time between adolescence (15–18 years) to emerging adulthood (19–23 years) and the mid-to-late twenties (24–28 years). The study focused on home preparations, dietary quality and meal preparation. The findings suggested that food skills and behaviours learned in adolescence were sustained later in life. From that study, food preparation taught to adolescents may have some effect on altering dietary behaviour.

In comparison to Robinson-O’Brien et al.’s review( Reference Robinson-O’Brien, Story and Heim 22 ) of garden-based nutrition interventions, the findings from the current review showed that they have the potential to promote an increase in preferences and improve dietary intake concerning fruit and vegetables. Four studies in our review reported that adolescents’ exposure to garden-based nutrition education was associated with an increase in fruit and vegetable intake( Reference Morgan, Warren and Lubans 35 , Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 , Reference McAleese and Fada 64 , Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 ). One study reported no improvement in fruit and vegetable intake( Reference Jaenke, Collins and Morgan 34 ). It is inconclusive for the long-term dietary intake of fruit and vegetables based on garden-based interventions. With regard to garden-based interventions, some studies provided pre and post( Reference Ratcliffe, Merrigan and Rogers 67 ) or only post-intervention data( Reference Evans, Ranjit and Rutledge 57 ), some did not include a control condition or included control and comparison groups but assigned only one group per condition, and could have resulted in possible statistical outcomes due to clustering.

Of the articles reviewed for adolescents’ attitudes and perceptions of food literacy, only seven studies used qualitative methods alone( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 37 , Reference Swaminathan, Thomas and Kurpad 47 , Reference McKinley, Lowis and Robson 53 – Reference Lukas and Cunningham-Sabo 55 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 72 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 73 ). Two of the articles used qualitative methods to assist in quantitative methods( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 37 , Reference Swaminathan, Thomas and Kurpad 47 ). The overall consensus from adolescents and their attitudes to food literacy in the school environment were that students held a clear understanding on what food items constitute healthy and unhealthy eating( Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 72 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 73 ) and described an overall positive experience with the school food programmes that are integrated into the school curriculum( Reference Lukas and Cunningham-Sabo 55 ). The results from qualitative studies investigating adolescent perspectives of the term ‘food literacy’ have revealed that there are multiple discourses on the term( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 37 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 72 , Reference Bohm, Lindblom and Åbacka 73 ). Adolescents appear to rank food and nutrition knowledge as more important than food skills and food capacity (positive attitudes towards cooking and nutrition knowledge)( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 37 ). A majority of students did not apply the food knowledge that they learned in home-economics classes due to low confidence in cooking skills and the food environment surrounding their school and home.

Of the articles reviewed for home-economics teachers’ attitudes and perspectives on food literacy, only five studies used qualitative methods( Reference Ronto, Ball, Pendergast and Harris 30 – Reference Dewhurst and Pendergast 32 , Reference Pendergast and Dewhurst 36 , Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 39 ). The studies identified that home-economics teachers rated aspects of food literacy, including cooking food, the nutritional content of food, and food safety and hygiene practices, as important skills. However, school food environments are not comprehensively supportive of food literacy. The findings from home-economics teachers’ attitudes and perspectives on food literacy programmes in secondary schools suggest that there may be some external factors affecting home-economics teachers’ ability to present culinary skills effectively to secondary-school students( Reference Ronto, Ball, Pendergast and Harris 30 , Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 38 ). External factors identified by Ronto et al.( Reference Ronto, Ball and Pendergast 38 ) were materials and facilities, human resources, non-supportive school canteen systems, negative role modelling and the importance of home economics from a parent’s perspective( Reference Ronto, Ball, Pendergast and Harris 30 ). Increased internal support from school leadership and healthy school food environments could assist home-economics teachers’ attitudes and perspectives on food literacy programmes taught in secondary schools.

Future research conducted in the field of food literacy in the school environment should focus on providing teachers with greater support and adequate training in nutritional knowledge, a universal definition, and evaluation techniques and instruments to measure all aspects of food literacy. None of the studies reviewed incorporated a validated and reliable tool to measure multiple constructs of food literacy. Studies investigating food literacy have measured only one or two aspects of the concept, mainly nutritional knowledge and food preferences. It appears further research is required to develop a valid and reliable tool that measures all attributes that cover the food literacy concept. Only one study utilised a randomised controlled trial research design, and thirteen studies utilised a quasi-experiment and one study used a pre–post intervention, resulting in an inability to assess causality between food literacy and dietary intake. Future studies examining dietary behaviour should include a theoretical basis for programme development. Given that food and nutrition literacy is a context-specific concept, the development of a valid and reliable tool to assess adolescents’ food literacy in the school setting could help to overcome the challenges of food and nutritional knowledge assessments in the school setting, tailor targeted evaluation programmes and identify gaps in school food literacy programmes.

Strengths and limitations of the systematic review

As a strength, the systematic review followed the PRISMA reporting guidelines. Second, the review included qualitative studies to ascertain adolescents’ and home-economics teachers’ perspectives on food literacy interventions in secondary schools. As food literacy is an emerging term in the literature, qualitative research can assist in understanding the facilitators and barriers to effective school-food based interventions( Reference Dixon-Woods, Fitzpatrick and Roberts 23 ).

The main limitation of the review’s design is the inclusion of a broad range of studies. As a result, a meta-analysis could not be conducted. Definitive conclusions from the studies reviewed could not be determined due to multiple definitions of the term food literacy( Reference Truman, Lane and Elliott 77 ). Due to the variations in definitions used across reviewed studies, it was challenging to incorporate strict parameters regarding only essential terms. Finally, the relative effectiveness of each different intervention could not be determined or generalised. Most of the studies measuring food knowledge and dietary intake were based on self-reported measures that may influence the reporting of actual and ideal dietary intake.

Conclusions

In the current systematic review, we reviewed and synthesised the literature on food literacy interventions in secondary schools and reported on the associations among home-economics teachers and adolescents and their effects on dietary outcomes. The review identified that food literacy interventions conducted in a secondary-school setting have been useful in improving food and nutritional knowledge. There was only one study identified in the review that indicated any effect on long-term dietary behaviour. That study evaluated the involvement in food preparation activities in adolescence and into early adulthood. To date, there appears to be no consensus on the definition of food literacy, which has resulted in difficulties in developing a valid and reliable measure resulting in minimal empirical evidence regarding measuring food literacy in the adolescent population. The evidence presented in the review recommends the creation and adoption of a validated and reliable tool to measure food literacy attributes. Further high-quality randomised controlled trials and longitudinal studies could then be conducted to ascertain dietary behaviours among adolescents.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to acknowledge the assistance of the academic librarian, Ms Nikki May, who helped develop the search terms for this paper. Financial support: The systematic review reported in this paper is part of a PhD project in the College of Education, Psychology and Social Work at Flinders University. This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or non-for-profit sectors. Conflict of interest: None. Authorship: C.J.B., P.R.W. and M.J.D. formulated the research questions, designed the study and wrote the article. All authors contributed to the editing of the literature review. Ethics of human subject participation: Ethical approval was not required as the paper is a systematic review and the findings of existing studies were available in the public domain.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1368980019001666