The introduction of antipsychotic medication benefitted many patients and helped to initiate the wave of discharges from psychiatric hospitals. Unfortunately, one in four patients with schizophrenia fails to respond to antipsychoticsReference Kane1 and continues to experience persistent auditory hallucinations, which have a major impact on their lives and can lead to suicide.Reference van and Kapur2 In an attempt to tackle this problem we developed a novel therapy to give patients control over their ‘voices’. The rationale derived from the observation that when people are asked about the worst aspect of hearing voices their invariable response is the helplessness. However, research has shown that patients who can initiate a dialogue with their voice feel much more in control.Reference Nayani and David3 Patients are often advised by professionals to ignore the voices and not to engage with them. However, the approach of Romme and colleaguesReference Romme, Escher, Dillon, Corstens and Morris4 of encouraging patients to enter into a dialogue with their voices has proved to be therapeutic. Furthermore, the association between trauma of various types in early life and the later development of auditory hallucinations is evidence for an understandable psychological origin for voices, although the exact mechanism has yet to be established.Reference Read, Fink, Rudegaier, Felitti and Whitfield5,Reference Bebbington, Jonas, Kuipers, King, Cooper and Brugha6 Some patients realise that their low self-esteem, induced by traumatic childhood experiences, is echoed by the voices that harass them. The development of persecutory auditory hallucinations can be formulated as an exteriorisation of a severely critical component of the psyche that cannot be tolerated.Reference Corstens, Longden and May7 If this is correct, then ignoring the voices negates the possibility of reassimilation of this rejected component of the patient's internal world. In 26 people who heard voices, Chadwick & BirchwoodReference Chadwick and Birchwood8 studied their experiences and beliefs about the voices. All participants interviewed who heard voices giving them commands, held additional beliefs that if they disobeyed, they would be punished or even killed. These authors developed a therapy based on asking the patients to test their belief in the dire consequences of disobeying these commands, a strategy that met with some success. An alternative approach of facilitating a dialogue between the patient and their persecutor in which the patient is enabled to gain control and the persecutor mellows, has determined the nature of our novel therapy.

Method

It is very difficult to establish a dialogue with an invisible entity that repeats the same stereotyped abusive phrases regardless of the patient's response. It was considered that if the persecutor were to be given a human face and made responsive to the patient's speech, a dialogue between the patient and their persecutor could be established with the assistance of a therapist. The therapy is based on computer technology that enables each patient to create an avatar of the entity they believe is talking to them. Construction of an avatar requires a program to create a face, animation software to synchronise lip movements with speech, and software to enable the therapist to speak through the avatar with the voice the patient hears. Commercial software was available for face construction (Facegen Modeller version 3.5.1 for Windows; Singular Inversions, Toronto, Canada; www.facegen.com) and for animation (Annosoft Real-time LipSync SDK 4.0.0.0 for Windows; Annosoft, Richardson, Texas, USA; www.annosoft.com/microphone-lipsinc), but nothing existed to reproduce the voice of the patient's persecutor. Software was developed in-house by M.-H., consisting of programs for building a range of transforms of the therapist's voice, for selection of a voice by the patient, and for the real-time voice transformation. The voice conversion technology was constructed using the approach developed by StylianouReference Stylianou9 whereby a probabilistic linear transform is applied to the speech spectral envelope in combination with pitch scaling. On average it takes 15 min for the patient to choose the face (online Fig. DS1), and 25 min to choose the voice. Patients who did not visualise a face were asked to select a face they would feel comfortable talking to. Patients hearing multiple voices were asked to focus on the dominant voice, or the voice they would most like to be rid of.

During the therapy sessions, the avatar's utterances were produced by the therapist, then voice transformed and played to the patient in another room together with the animated face. The patient's responses were then fed back to the therapist so that the patient effectively interacted with the avatar as an external entity. The therapist could also communicate instructions or advice and encouragement to the patient in their normal voice over a separate audio channel, without involving the avatar. Switching between the two modes of communication was effected via a simple graphical interface. Sound was transferred between the two computers over a standard network connection. The patient was seated in a room and faced a monitor on which their avatar was shown. The therapist sat in an adjacent room and also viewed a screen on which the avatar appeared.

There was an additional voice-changing screen. Clicking on the right side of the screen allowed the therapist to speak to the patient through the avatar using the morphed voice. Clicking on the left side of the screen enabled the therapist to speak to the patient in their normal voice. The patient was prompted by the therapist to enter into a dialogue with their avatar in which the therapist encouraged them to stand up to the avatar. The therapist controlled the avatar so that it progressively came under the patients' control. In addition, over the course of the therapy the character of the avatar was changed by the therapist from being abusive to becoming helpful and supportive of the patient. Our assumption was that patients who are assisted by the therapy to establish control over the avatar would be able to transfer that experience to the persecutory voice. We also considered it possible that the transformation of the avatar from a hostile entity to a well-intentioned supporter might enable the patient to reintegrate the exteriorised component of their psyche. Each session was recorded and transferred to an MP3 (portable digital audio) player for the patients to use outside of the sessions to reinforce their control over their persecutor.

In case participants became very anxious on seeing and hearing the avatar, a prominent red stress button was made available and its purpose explained. Pressing the button caused the avatar to disappear from the monitor, to be replaced by a scene of a tropical beach accompanied by soothing music.

Evaluating the therapy

Design of the trial

This was a Phase II proof-of-concept study of the efficacy of a novel therapy. For this purpose the design chosen was a randomised, partial crossover trial, with follow-up of patients who had received the treatment. Patients who were randomised but dropped out of treatment yielded no further data. Choice of the number of sessions was determined by practical considerations: the short duration available to complete the trial (11 months) and the fact that there was only one therapist, J.L. These factors led to a decision to limit the therapy to 6 sessions of 30 min duration with a 1-week follow-up. An additional follow-up was planned for 3 months after the last therapy session.

Choosing a control treatment for comparison with avatar therapy was problematic and after some deliberation, it was decided that the control group would receive treatment as usual (TAU) for 7 weeks before being offered avatar therapy, although it was recognised that this would not control for the additional attention paid to the patients. Treatment as usual consisted of the patient's ongoing antipsychotic medication prescribed and supervised by their referring psychiatrist.

The power calculation was based on a drop-out rate of 25% and a reduction in the Omnipotence score (see below) of 35% with a power of 80% at P<0.05. This degree of reduction was judged to be clinically meaningful. The two inclusion criteria for the study were: hearing persecutory voices for at least 6 months, which had not responded adequately to antipsychotic medication irrespective of diagnosis, and age between 14 and 75. Parental consent was obtained for those under 18. Exclusion criteria were organic brain disease and substance misuse. The study was approved by the West Kent Research Ethics Committee.

Recruitment of patients

Participants were recruited from the community mental health teams in Camden and Islington Mental Health Trust.

Randomisation procedure

After baseline assessment, patients were randomised into one of two groups using a computer-generated series with blocks of 12, generated by an independent statistician. The immediate therapy group entered straight into the 7-week block of avatar therapy, whereas the delayed therapy group received TAU for 7 weeks (control block) and were then offered a 7-week block of avatar therapy. This enabled us to look at within- as well as between-group effects. The immediate therapy group did not crossover into a no-therapy block as we expected the therapy to have carry-over effects.

Assessment of patients

Both groups of patients were assessed at each time point by M.A., a user-researcher who knew neither the group to which each patient was assigned, nor the design of the trial. Interrater reliability between M.A. and J.L. was assessed for 10 patients by Cohen's kappa and ranged from 0.84 to 0.94. Three questionnaires were administered.

(a) The Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PSYRATS)Reference Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier and Farragher10 hallucinations section, which captures information on the frequency and disturbing qualities of the hallucinations.

(b) The revised Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire (BAVQ-R),Reference Chadwick, Lees and Birchwood11 which focuses on the patient's beliefs about the ‘voices’, and thus indexes how likely the voices are to affect behaviour. Two of the five subscales of this instrument were selected a priori for analysis as most pertinent to the predicted effects of the therapy. The Omnipotence scale measures the power of the voice as perceived by the patient, which was expected to reduce since the avatar progressively yields to the patient's assertiveness. The Malevolence scale measures the patient's beliefs about the evil intentions of the voices towards them, which were expected to improve since the avatar is manipulated by the therapist from an initial persecutory role to one supportive of the patient. The scores on these two scales were analysed separately and as a sum total. The key question was whether the changes in the avatar would alter the patients' experience of the voices they hear.

(c) The Calgary Depression Scale (CDS),Reference Addington, Addington and Maticka-Tyndale12 since depression is common in schizophrenia.Reference Leff, Tress and Edwards13

Data analysis

Two main analyses were performed: first a comparison of the immediate therapy group with the delayed therapy group to establish whether the therapy had an effect on the three main outcome measures. The dependent variable was the change score (absolute difference) between the pre-treatment measure and the post-treatment measure. These were entered into a one-sample t-test (null hypothesis: there is no significant effect of the therapy on each outcome measure). All t-tests were two-tailed.

The second analysis was within-group, to directly compare the effects of therapy on the delayed therapy group. This was a repeated measures ANOVA on the raw scores at each of the three time points (T 0: baseline; T 1: post 7-week control block; T 2: post 7-week therapy block). If there was a significant effect of time, we then used post hoc t-tests to see whether this was over the therapy block (T 1 to T 2) rather than over the control block (T 0-T 1).

We also undertook a third analysis to investigate whether therapy gains were maintained for both groups at the 3-month follow-up. We performed paired t-tests comparing the 3-month data with two time points: (a) pre-treatment v. follow-up (to see whether patients were still improved compared with baseline); (b) post-treatment v. follow-up (to see whether patients continued to improve after avatar therapy).

In addition, we pre-planned a subsidiary analysis of the suicide item on the CDS, rated 0-4, because of the high risk of suicide in patients with command hallucinations.

We used independent-sample t-tests to look for any failure of randomisation in terms of retaining balance between the two groups on the three main outcome variables both at the time of randomisation and at the first follow-up after some patients had dropped out of both groups. The statistical analyses were conducted by A.L.

Results

Initially, very few referrals for the therapy were made, probably because of the untried nature of the therapy. A steady rate of referrals was only achieved after some dramatic successes with the therapy. Eventually, 27 patients were recruited, all of whom met the inclusion criteria. However, 1 patient refused when approached by the researcher. For demographic data on the 26 included patients see Table 1.

Table 1 Sociodemographic data of patients (n = 26)

| n | |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 16 |

| Female | 10 |

| Employment | |

| None | 14 |

| Retired | 3 |

| Student | 6 |

| Part time | 1 |

| Full time | 2 |

| Education | |

| No qualifications | 7 |

| GCSE | 10 |

| A level | 3 |

| Degree | 6 |

| Voice duration, yearsFootnote a | |

| 1-5 | 8 |

| 6-10 | 3 |

| >10 | 15 |

| Medication compliance | |

| None | 2 |

| Partial | 2 |

| Complete | 22 |

a. Range 3-30.

The duration of hearing voices for the majority exceeded 10 years. All but two patients were completely or partially adherent with antipsychotic medication. One had stopped the medication 9 months prior to the study because of excessive weight gain and the other participant had stopped 3 years before the study as it had not diminished his hallucinations.

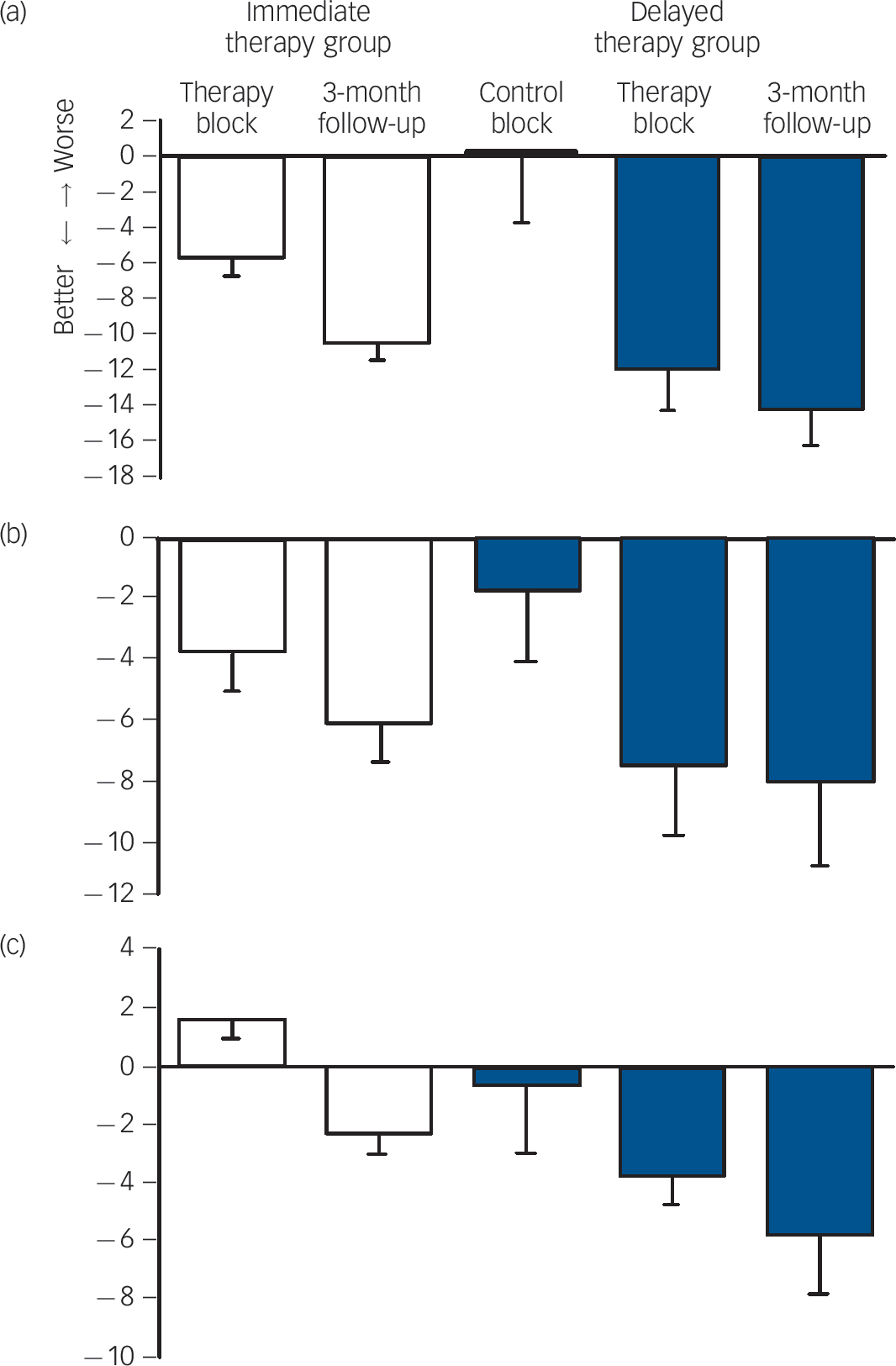

In total 14 patients were randomly assigned to the immediate therapy group and 12 to the delayed therapy group. In our comparison of the immediate therapy group with the delayed therapy group to establish whether the therapy had an effect on the three main outcome measures we found significant positive effects for both the PSYRATS total score (P = 0.003), with an average reduction of −8.75 points, and the BAVQ-R total score (P = 0.004), with an average reduction of −5.88 points; but we found no significant effect on CDS score (P = 0.423), with an average reduction of only −0.94 (Fig. 1).

Our second, within-group, analysis that directly compared the effects of therapy on the delayed therapy group (n = 8), confirmed the findings from the first analysis, with significant positive effects for the following measures: (a) PSYRATS total score (P = 0.006), with the reduction in score occurring at the expected time point (T 0-T 1 P = 0.960; T 1-T 2 P = 0.027), (b) BAVQ-R score (P = 0.014), with the reduction in score again occurring at the expected time point (T 0-T 1 P = 0.660, T 1-T 2 P = 0.042) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Effect sizes of avatar therapy on the three main outcome measures for both patient groups.

(a) Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale; (b) revised Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire; (c) Calgary Depression Scale. The immediate therapy group is shown in white and the delayed therapy group in blue. A negative score indicates improvement (post-therapy minus pre-therapy).

The two outcome measures that reduced significantly across both analyses (PSYRATS and BAVQ-R) are measures of the frequency and quality of the auditory hallucinations, and the delusions patients develop about the voices. The third measure of depressive symptoms was not significantly reduced in any of the comparisons. The effect size of the therapy was 0.8.

Three months after the therapy ended we successfully followed up the 16 patients who had received the therapy (immediate therapy group n = 8, delayed therapy group n = 8). We collected full data on 14 patients. One patient lost concentration during the BAVQ-R, which was incomplete, and another patient only consented to complete the PSYRATS. In the third analysis, which investigated whether therapy gains were maintained for both groups at the 3-month follow-up, we found that compared with the pre-treatment scores, the patients remained significantly better on both the PSYRATS (P<0. 001), with an average reduction of 12.25 points, and the BAVQ-R total score (P = 0.014), with an average reduction of 7.00 points. We also found an effect on the CDS score, P = 0.036 with an average reduction of 4.13 points. At the post-treatment time point, we found positive changes for both the PSYRATS (P<0.029), with an average reduction of 3.5 points, and the CDS score (P = 0.052), with an average reduction of 2.8 points (Fig. 1). This indicates that both the PSYRATS and the CDS continued to improve after the therapy ended. There was no significant effect on the BAVQ-R total score (P = 0.611) with an average reduction of only 1.14 points. All three patients whose voices ceased during the therapy were still free of them at the 3-month follow-up. Means and standard deviations for each group at each time point are shown in Table 2.

The average reduction in the BAVQ-R Omnipotence subscale score between the beginning and the end of the therapy was 29.0% (pre-treatment mean, 12.2; post-treatment mean 8.5), close to the reduction of 35% used for the power calculation. The average reduction in this score between the beginning of the therapy and the 3-month follow-up was 37.9% (3-month follow-up mean, 7.4).

Table 2 Mean values (s.d.) for the main three outcome measures at all time points

| Immediate therapy group, mean (s.d.) | Delayed therapy group, mean (s.d.) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Post- treatment | 3-month follow-up | Baseline | Pre- treatment | Post- treatment | 3-month follow-up | |

| Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale | 29.25 (4.86) | 23.63 (8.03) | 18.88 (8.90) | 31.75 (5.39) | 31.88 (8.10) | 20.00 (13.10) | 17.75 (9.41) |

| Revised Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire | 22.63 (7.58) | 18.88 (7.24) | 15.57 (8.96) | 21.38 (8.85) | 21.00 (11.33) | 12.37 (12.61) | 13.43 (9.38) |

| Calgary Depression Scale | 6.88 (4.02) | 8.50 (5.29) | 3.71 (2.98) | 9.25 (2.37) | 8.63 (8.49) | 4.00 (1.41) | 2.88 (3.52) |

Table 3 Comparison of the baseline means (s.d.) for the three main outcome measures between the delayed therapy and the immediate therapy group after randomisation (baseline) and at the first follow-up, after some patients had dropped out of both groupsFootnote a

| Baseline | First follow-up | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (s.d.) | t (d.f. = 24) | P | Mean (s.d.) | t (d.f. = 14) | P | |

| Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale | 0.79 | 0.44 | 0.97 | 0.35 | ||

| Delayed therapy group | 33.75 (5.55) | 31.75 (5.39) | ||||

| Immediate therapy group | 32.00 (5.71) | 29.25 (4.86) | ||||

| Revised Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire | –0.69 | 0.50 | 0.86 | 0.40 | ||

| Delayed therapy group | 9.17 (5.94) | 9.25 (6.69) | ||||

| Immediate therapy group | 10.93 (7.01) | 6.88 (4.02) | ||||

| Calgary Depression Scale | –1.15 | 0.26 | –0.30 | 0.77 | ||

| Delayed therapy group | 22.67 (9.41) | 21.38 (8.85) | ||||

| Immediate therapy group | 26.50 (7.53) | 22.63 (7.58) | ||||

a. There were no significant differences between the groups at either time point.

In our subsidiary analysis of the suicide item on the CDS, we found that by the end of the therapy sessions the score on this item had reduced significantly, P = 0.034 (mean pre-treatment 0.94; mean post-treatment 0.38).

Drop-out rate

Of the 14 patients in the immediate therapy group, 5 dropped out and one was excluded because of a change in medication. All 12 patients in the delayed therapy group were followed up after 7 weeks and were then offered the therapy. Eight accepted and were followed up again 1 week after the end of the therapy. Hence a total of 16 patients across both groups received the therapy and were followed up. The total drop-out rate was 9 out of 26 (34.6%). The refusal of four patients to accept the offer of therapy, and of five patients to complete their course of therapy is mainly accounted for by the fear instilled in patients by their ‘voices’, which often threaten them if they disobey.Reference Haddock, McCarron, Tarrier and Farragher10 Two patients heard multiple voices and could not concentrate on the avatar because the other voices spoke too loudly at the same time. It took considerable courage for some of the patients to face their avatar. One participant who had been sexually abused by an older man could not bear to see his face, which we deleted, but was able to speak with the avatar, and in fact the voice ceased after 13 years of torment.

In our analysis to test for failure of randomisation in terms of retaining balance between the two groups on the three main outcome variables (Table 3), we found no significant differences between groups both immediately after randomisation (immediate therapy group n = 14, delayed therapy group n = 12) or after drop out (immediate therapy group n = 8, delayed therapy group n = 8) (all P>0.25).

Discussion

We hypothesised that this novel therapy might achieve some reduction in the frequency and intensity of the auditory hallucinations. In the event, two of the three main outcome measures were significantly reduced immediately after avatar therapy: the PSYRATS and BAVQ-R. They are measures of the frequency and intensity of the auditory hallucinations, the disruption they cause to life, and the beliefs patients develop about their hallucinations, in particular their omnipotence and malevolence. Reductions of this degree are clinically important considering that the patients' hallucinations had failed to respond to many years of the most effective antipsychotic drugs available. The third measure was of depressive symptoms. Although this was not significantly reduced by the end of therapy, by the 3-month follow-up this variable significantly improved from baseline across both the immediate and delayed therapy groups. Depression is common in people with schizophrenia,Reference Leff, Tress and Edwards13 and although the therapy did not specifically target depressive symptoms, when patients were rated as having low self-esteem, attempts were made to improve their self-image, with success in some individuals. The significant reduction in the patients' suicidal intent is of considerable clinical import. We investigated whether the individuals who had dropped out had invalidated the randomisation and found that in terms of the three main outcome measures the equivalence of the experimental and control participants had not been affected.

Avatar therapy is very brief, never more than 7 sessions held weekly, each lasting no more than 30 min. In fact, the recordings show that the majority of dialogues with the avatar lasted 15 min or less. The additional time was occupied with the patient's report on the previous week before the dialogue ensued, and feedback following the session. The outcome that was unexpected was the abrupt cessation of the hallucinations in three of the patients, which remained absent at the 3-month follow-up. In two of the patients their voices stopped after the second session of therapy. One had been hearing the voice of the devil for 16 years and thanked us for giving him his life back. Another participant, for 3.5 years, had been woken every morning at 05.00 h by a woman's voice that continued throughout the day. He said ‘It's as if she left the room’.

How did the therapy work?

There are several possible explanations for the efficacy of avatar therapy. The therapist takes the patients' experiences at face value and assists them to actualise their persecutor, validating the patient's experience.Reference Stylianou9 Although patients interact with the avatar as though it is a real person, because it is their creation they know that it cannot harm them, as opposed to the voices, which they fear. They can take risks with the avatar, standing up to it and telling it forcefully to leave them alone, behaviour they would not attempt with their delusional persecutor. Once they gain the courage to confront the avatar, they learn to do the same with their persecutor, as evidenced by the significant reduction in the perceived power of their persecutor. During the course of therapy the avatar changes its nature, ceasing to abuse the patient after one or two sessions, and becoming friendly and supportive. The MP3, which is given to each patient to keep, contains all their recorded sessions. Both the therapist and the avatar encourage the patients to listen to their MP3 when harassed by the voices. We describe it to them as ‘a therapist in their pocket’. It is possible that the continued improvement after the end of the therapy was attributable to the use of the MP3. However, we did not quantify the patients' use of the MP3 during this period, so we can only speculate about this.

Many of the patients in our study had very low self-esteem. The link made by the therapist and the avatar between the patients' low self-esteem and the abuse from the voices, helped some patients to recognise that the voices originate within their own mind, and could ameliorate if the patient began to recognise their own good qualities.

Limitations of the study

By comparing avatar therapy with TAU we did not control for the time and attention paid by the therapist to patients receiving the therapy. In the proposed replication study we will include an active control of supportive counselling. We will also test the adequacy of the masking of the assessor. We did not conduct an intention-to-treat analysis since this is inappropriate for a Phase II trial of efficacy of a new treatment of unknown effect: ‘Phase II trials decide whether the new treatment is promising and warrants further investigation in a large-scale randomised Phase III clinical trial based on an observed response rate that appears to be an improvement over the standard treatment or other experimental treatments’.Reference Seymour, Ivy, Sargent, Baker, Rubinstein and Retain14

We have learnt that avatar therapy is not suitable for all patients, but this proof-of-concept study provides evidence that it is effective for those who can tolerate it. The high drop-out rate is a matter of concern and the acceptability of avatar therapy will be addressed in more detail by the Phase III replication trial, which is already funded.

For practical reasons only a single therapist delivered the therapy in the reported study. This raises the questions of whether the skills required to achieve these positive results can be taught to others, and the length of training necessary. In preparation for the independent replication trial in London, a technical manual and a clinical manual have been completed.

Funding

The study was funded by the National Institute of Health Research (RC-PG-0308-10232) and Bridging Funding from Camden & Islington NHS Foundation Trust.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.