Facial synkinesis is among the most invalidating consequences of peripheral facial palsy (PFP). It is defined as abnormal muscle contractions of one or many facial areas during volitional facial movement. Reference Kleiss, Beurskens, Stalmeier, Ingels and Marres1 Synkinesis has numerous functional and cosmetic adverse effects as it limits several day-to-day activities like speaking and eating. Reference Mehta, WernickRobinson and Hadlock2 Potential mechanisms for the development of synkinesis could be due to aberrant reinnervation, either by stimulation of neighbor axons in the context of myelin loss or due to hyperexcitability of the facial nucleus. Reference Kleiss, Beurskens, Stalmeier, Ingels and Marres1

From a research perspective, the use of a validated universal grading system for synkinesis would allow appropriate data pooling and help in establishing valid recommendations for clinical decision- making. Reference Wild, Grove and Martin3 From a clinical perspective, the evaluation of synkinesis through a patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) is critical to grasp the scope of the handicap that it causes. Reference VanSwearingen, Cohn, Turnbull, Mrzai and Johnson4 Observer-based evaluation of facial function often leads to an incomplete description of patient psychological distress and functional impairments that are caused by the sequelae of facial palsy. Reference Marsk, Hammarstedt-Nordenvall, Engstrom, Jonsson and Hultcrantz5

The Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire (SAQ) Reference Mehta, WernickRobinson and Hadlock2 was developed as a specific and validated PROM for synkinesis. While the original English version has demonstrated to be a reliable and valid instrument, there is no existing French equivalent. The purpose of the present study was to create a validated French version of the SAQ in accordance with international guidelines of translation and cultural adaptation.

The present study was approved by the Ethics Review Board of the Centre-intégré-universitaire-de-santé-et-de-services-sociaux du Nord-de-l’Ⓘle-de-Montréal (MP-32-2020-1952). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

The translation and cultural validation process respected international guidelines. Reference Wild, Grove and Martin3 A standard forward–backward translation procedure was adopted, with two independent certified translators who produced distinct translations from the original to the target language. Those two translations were merged by the senior researcher of the study. A third translator back-translated the reconciled version for review and identification of discrepancies.

The preliminary version was administered by the first author to 10 native French patients with PFP (women: 8; mean age: 47.4 (15.6)) for cognitive debriefing. Reference Wild, Grove and Martin3 Appropriate minor changes were then made to the preliminary version and the resulting French version of the SAQ (SAQ-F) was used for validation (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Synkinesis assessment questionnaire – French.

Validation of SAQ-F was conducted with a prospective cohort study including 25 patients with PFP and 25 controls who visited the Otolaryngology clinic for other indications than a PFP (ear infection, dysphonia, tonsillitis, etc.), from February to April 2020. Inclusion criteria were having a PFP and being 18 years old and older. Exclusion criteria were: (1) history of neurological disorders; (2) active psychiatric disease; (3) cognitive disorder; (4) inability to understand written and oral French. For the PFP participants, the severity of facial palsy was assessed using the Facial Nerve Grading System 2.0 (FNGS 2.0; also known as the House-Brackmann 2.0 score) Reference Vrabec, Backous and Djalilian6 and the Sunnybrook Facial Grading System (SB). Reference Ross, Fradet and Nedzelski7 These were chosen because each has been shown to have high inter-observer agreement and validity. Reference Fattah, Gurusinghe and Gavilan8 Specific subscores of synkinesis can be calculated from either scale to allow for more specific analyses. Patients completed the SAQ-F twice within a 2-week interval for test–retest reliability. None of the PFP patients were subject to changes in their treatment.

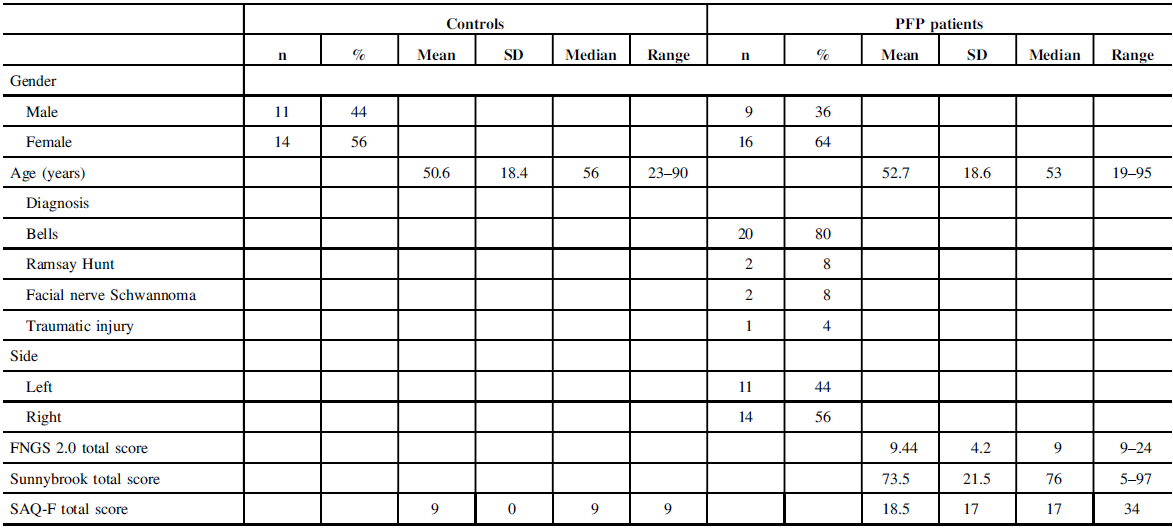

Of 50 respondents, 25 were PFP patients and 25 controls (Table 1), with 20 men (40%) and 30 women (60%). The average age was 51.6 (18.4) years for the entire sample, 52.7 (18.6) years in PFP and 50.6 (18.4) years in controls. The mean total SAQ score was 18.5 (95% CI 15.7 to 21.2, median 17, range 17–34) points in PFP group, and 9.0 (no variance) points in controls with a difference of −9.5 (95% CI −12.2 to −6.8) points and p-value < 0.0001. Of the PFP patients, 80% were diagnosed with Bell’s palsy and the remaining 20% were diagnosed with a PFP secondary to Ramsay-Hunt’s Syndrome, facial nerve schwannoma or traumatic injury. Severity of facial palsy was generally rated as light to moderate with both FNGS 2.0 and SB scales: mean FNGS 2.0 score was 9.4 (4.2) and mean SB score was 73.5 (21.5).

Table 1: Patients demographics

Note: PFP= peripheral facial palsy; n = number; SD = standard deviation; Facial Nerve Grading Scale 2.0 (FNGS 2.0) scores: 24 = total palsy; 4 = no facial palsy. Sunnybrook (SB) scores: minimum possible = 0 or total palsy; maximum possible = 100% or normal; SAQ scores: 9 = no synkinesis; 45 = severe synkinesis.

The analyses were performed using Stata/IC Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station (StataCorp LP, TX, USA). The internal consistency of SAQ-F was assessed by using a Chronbach’s alpha along with its lower 95% confidence limit (95% CL). Alpha ≥ 0.9 was considered excellent, ≥ 0.8 good, ≥ 0.7 acceptable, ≥ 0.6 questionable, and ≥ 0.5 poor. The known-group validity (PFP vs. controls) was assessed by using a t-test for independent groups in case of total score, and the Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric test for the items’ ordinal scores. A two-tailed p-value ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The test–retest validity of the SAQ-F scale was assessed by employing a Spearman rank correlation coefficient. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to approximate the construct structure of the SAQ-F and included only PFP patients. The goal was to determine whether the SAQ-F measures only one latent trait (= signs of facial paralysis) or if there are other possible significant latent variables affecting the results. The results were analyzed graphically. After the orthogonal varimax rotation was applied, retained and excluded factors were explored visually on a scree plot along with a parallel analysis. Pearson’s product-moment correlation was used when comparing the SAQ-F total score with the synkinesis subscores obtained from the Sunnybrook and FNGS 2.0 scales. Fisher’s transformation was used for both Spearman and Pearson’s tests. Correlation < 0.2 was considered poor, from 0.21 to 0.4 fair, from 0.41 to 0.6 moderate, from 0.61 to 0.8 substantial, and >0.8 perfect.

Results showed that the internal consistency of the SAQ-F was good with alpha of 0.87 (lower 95% CL 0.82). Results of the test–retest reliability were substantial to perfect for the total score as well as for all nine items individually (0.96, 95% CI 0.93 to 0.98) (Table 2). Known-group validity of SAQ-F appeared to be high as there were significant differences between groups in the total score and in seven out of nine items’ scores (p < 0.01) (Table 3). Construct validity of the SAQ-F was tested by an exploratory factor analysis (Table 4 and Figure 2). The parallel analysis of the scree plot showed that SAQ-F had three factors with positive Eigen values above the parallel analysis line. However, the Eigen values of the second and third factors were as low as 1.2 and 0.6 respectively and were disregarded for retaining. Thus, the SAQ-F was considered to have a unidimensional structure with one factor, whose Eigen value was 3.1. When assessing the criterion validity based on the 25 PFP patients, Pearson’s product–moment correlation of the SAQ-F total score and the FNGS 2.0 synkinesis subscore was not significant (r = −0.23; 95% CI: -0.57 to 0.18). The Spearman’s rank correlation of SAQ-F total score with Sunnybrook synkinesis subscore was also not significant (r = −0.19; 95% CI: −0.55 to 0.22).

Table 2: Test–retest validity of the SAQ-F (including both PFP and control groups)

Note: SAQ-F = Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire – French; PFP = peripheral facial palsy; CI = confidence interval.

Table 3: Know-group validity – differences in SAQ-F scores between PFP and control groups

Note: aIndependent groups t-test; bKruskal–Wallis test; SAQ-F =Synkinesis Assessment Questionnaire – French; PFP = peripheral facial palsy; CI = confidence interval.

Table 4: Rotated factor loadings (pattern matrix) and unique variances

Figure 2: Scree plot of the factor analysis along with parallel analysis of the SAQ-F for construct validity.

In this study, we presented the translation and validation of the SAQ-F, a French patient-centered questionnaire based on the original English SAQ. Reference Mehta, WernickRobinson and Hadlock2 The SAQ scale allows to quantify the patient’s perception of synkinesis’ severity and thus allows to adapt the management and overall care of synkinesis, to fit the patient’s expectations. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation is necessary in the use of PROM questionnaires, to avoid misinterpretation while using questionnaires developed in other countries. Reference Wild, Grove and Martin3 To our knowledge, no other study validated the SAQ scale in French. Thus, the SAQ-F will be highly relevant for many clinical and research settings in Quebec and other French-speaking regions.

We translated and validated the SAQ-F according to the best practice’s international guidelines. Reference Wild, Grove and Martin3 Our results showed that the SAQ-F has good internal consistency, a high test–retest reliability, a high known-group validity, allowing to distinguish between controls and PFP patients, as well as good construct validity. Compared to the original version, the SAQ-F presented a slightly higher internal consistency (0.87 for SAQ-F and 0.80 for SAQ) and test–retest reliability (0.96 in our study and 0.881 in the original one).

Correlations with synkinesis subscores of clinician-based questionnaires were not significant. Other studies already reported discrepancies between PROM and clinician-based physical examination. Reference Marsk, Hammarstedt-Nordenvall, Engstrom, Jonsson and Hultcrantz5 A high correlation between both measures is probably not to be expected, and both of them should be taken for a complete overview of the synkinesis severity. Reference Kleiss, Beurskens, Stalmeier, Ingels and Marres1,Reference Mehta, WernickRobinson and Hadlock2

This study is not without limitation. As the data comes from a small number of patients, nonsignificant results regarding criterion validity could be due to lack of power. Due to practical reasons, the group size was limited to 25 patients, which is nonetheless comparable with many other PROM studies in the literature about PFP. Reference Luijmes, Pouwels, Beurskens, Kleiss, Siemann and Ingels9 Further research may reveal valuable information about SAQ-F psychometric properties by employing, for example, item response theory analysis (IRT). Reference Nguyen, Han, Kim and Chan10

The SAQ-F was found to be a reliable, easy-to-use, and valid unidimensional scale to assess synkinesis after PFP. The SAQ-F should be accompanied by clinician-based scales to provide valuable additional information on the severity of synkinesis.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Anne-Marie Chouinard for her contribution in the development of the research protocol.

Disclosure

None.

Statement of Authorship

SM and LG participated in the development of the research protocol, recruitment of patients and the redaction of the article. AR and KM participated in the redaction of the article. MS participated in the analysis of data and redaction of the article. SPM supervised each step of the research.